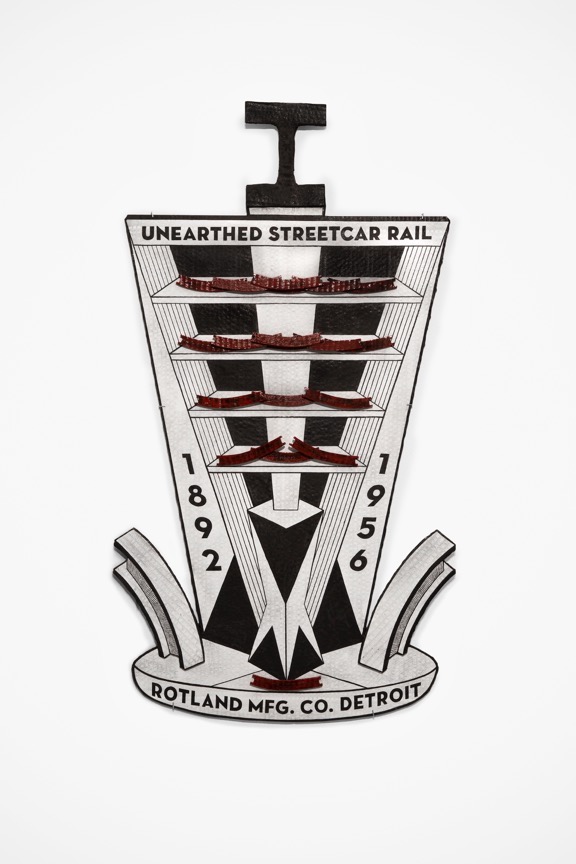

“Compo/Site”, Installation view at the Scarab Club, All images: Ryan Standfest

The current politically-charged discourse surrounding the construction of a wall at a secured southern border, is as much as anything a conceptual conversation giving material form to immaterial psychological barriers. The “Trump wall,” conceived as a talking point in the 2016 presidential campaign, is representative of something far more than the control of illegal immigration traffic. Its physical manifestation in the public imagination is a singular structure that forcefully cuts through the landscape, creating a geographic forcefield through which no body nor any view may pass. It is a potent symbol that negates the very notion of free passage.

Underlying the idea of it, is a sense of paranoia and xenophobia; the need to separate oneself from “the other.” It is also about turning inward, and embracing the notion that one’s sense of place is not a shared space, but an individually-owned and protected one. An isolationist perspective in which landscape itself must be divided, detached and organized into manageable zones to ease psychogenic stresses.

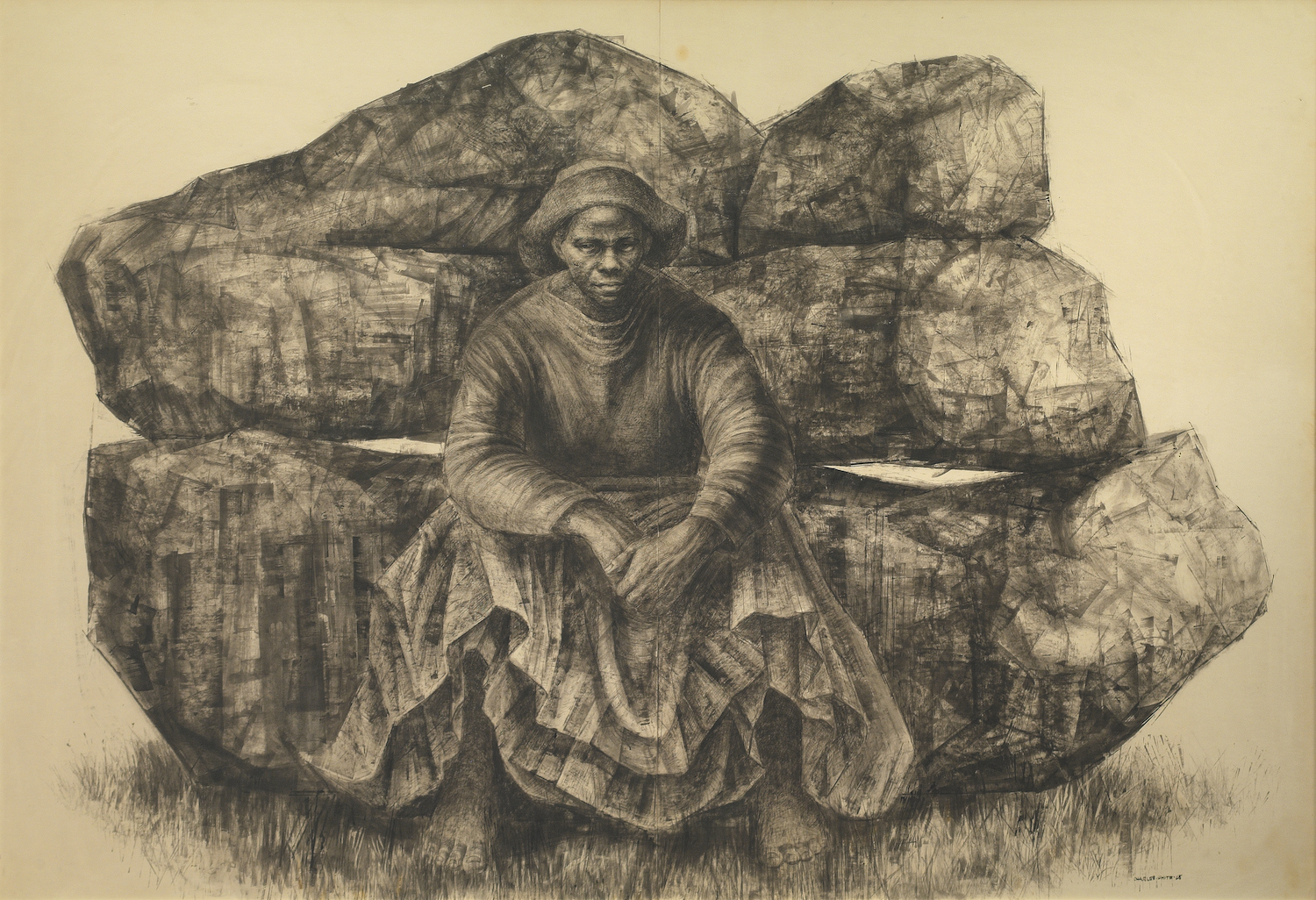

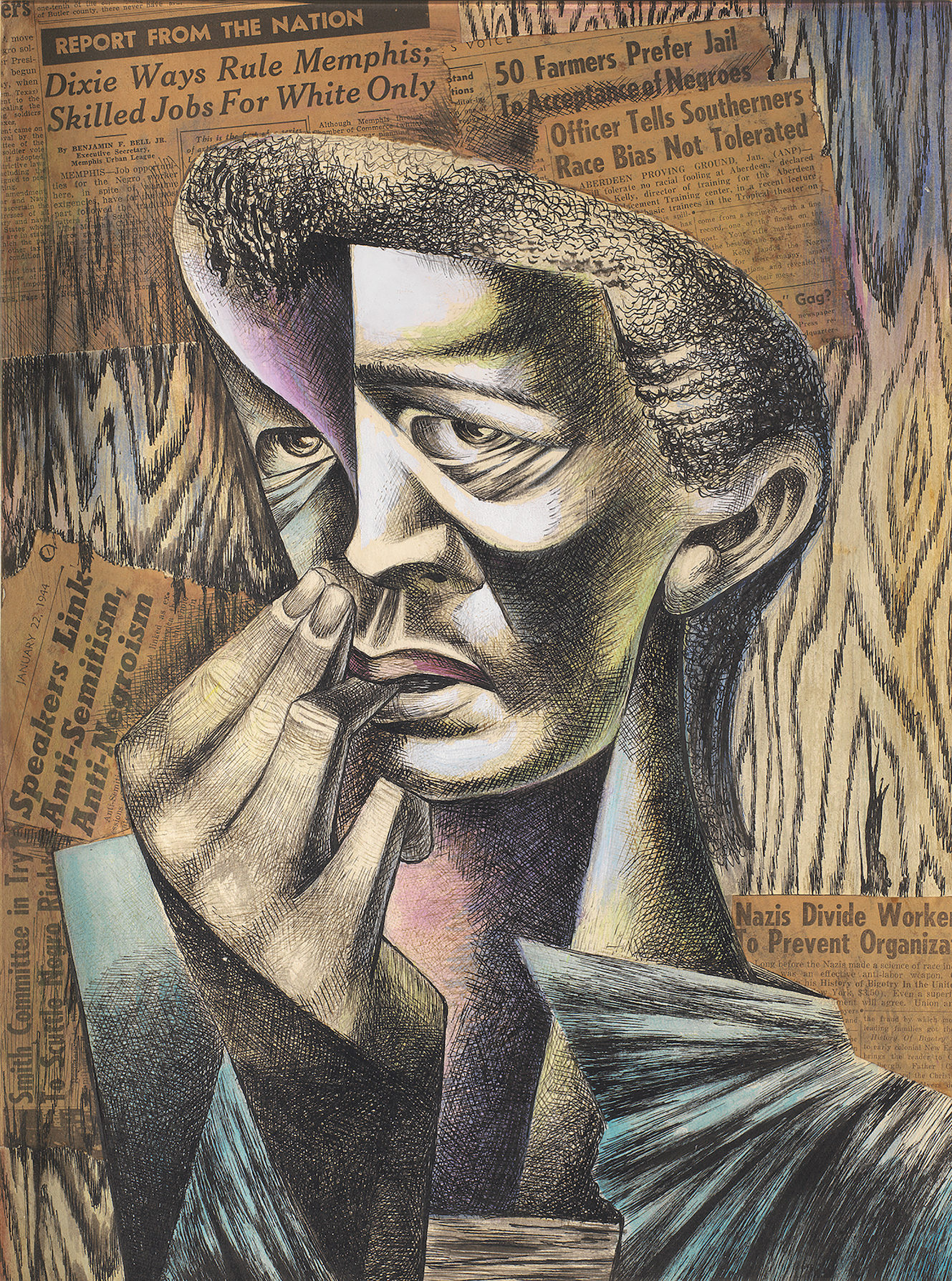

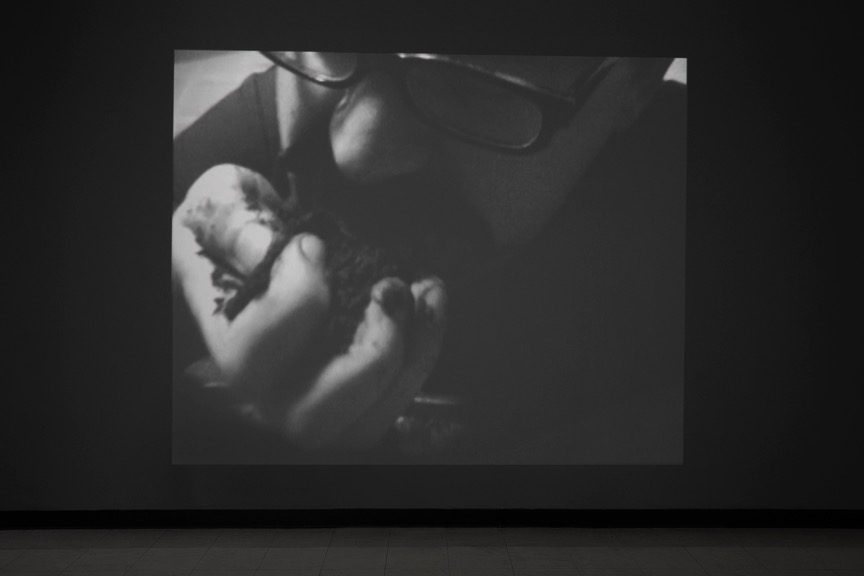

“Compo/Site” at The Scarab Club, is an exhibition of forty works by six artists, all employing print media to investigate environmental psychology and the parameters of space and place. With a few exceptions, there is the noticeable absence of representations of the human body in most of the work on view, and yet there is a cultivated awareness throughout of human motivation behind structures that reshape physical landscapes into cognitive ones. Each of these artists question how we construct place and manufacture a phantom ownership over space—a personal space and a public space, a space for desire and a space for loss.

Zach Fitchner: “Housing Units”, Installation, monoprints on cut paper, 20 x 16 inches each, 2019

In Housing Units and Passenger Plane, Zach Fitchner assembles two installations within the gallery that proposes a set of containers, both private and public. Housing Units, a row of five monoprints each measuring 20 x 16 inches, employs a reconfigured matrix of wood relief and half tones, to minimally suggest a house on each shaped sheet of paper. The use of wood grain and screen pattern bridges the organic and the mechanical, but also summons two print processes to speak to concepts of pre-fabrication in housing. Fitchner smartly makes use of the monoprint process, whereby multiple iterations of an image can be achieved from a single changeable matrix, to underscore the development of postwar suburban communities in which a housing template was reproduced endlessly with minor variation in decorative choices. It is a visually stunning representation of the suburban phenomenon where the concept of community is performed as assimilation within a highly planned environment.

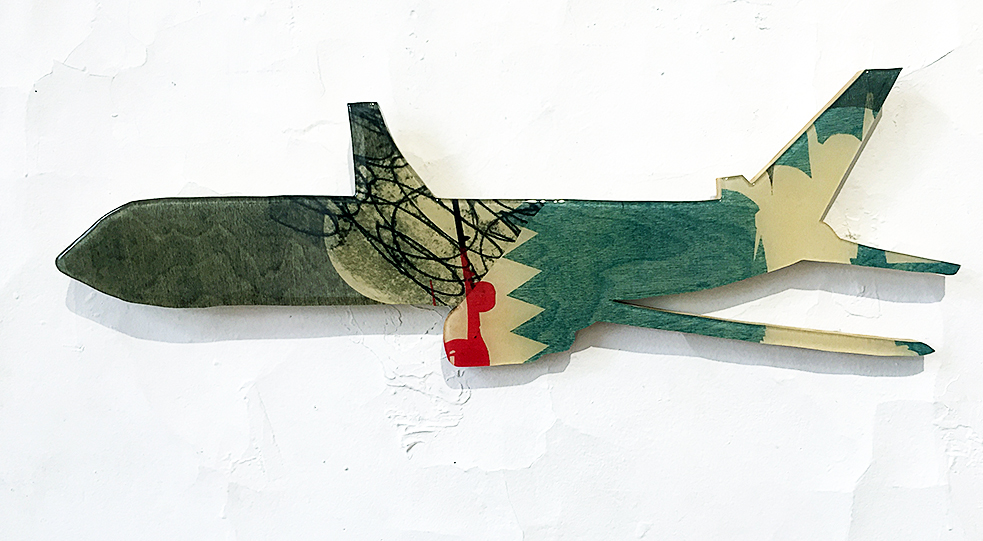

Zach Fitchner: “Passenger Plane”, installation, monotype, lithography and relief on panels with supergloss epoxy resin, 6 x 22 inches each, 2015-2016

Zach Fitchner: “Passenger Plane”, detail, monotype, lithography and relief on panel with supergloss epoxy resin, 6 x 22 inches each, 2015-2016

With Passenger Plane, Fitchner transforms the white of the gallery wall into an airspace with seven passenger jets taking off and landing. The jets are a mixture of monotype, lithography and relief prints, with a supergloss epoxy resin on cut plywood panels each measuring 6 x 22 inches. The programmatic routine of air flight is disrupted with the organic, printed fuselage skins—a patchwork camouflage that enlivens the representations of these flying containers as they glide over the irregular plaster surface of the Scarab Club’s gallery walls, which in this context resembles a sculpted airspace of stylized clouds. The sighting of Fitchner’s installations work quite well: suburbs and air traffic—a basic mechanics of procedural living speaking to one another. You can practically hear the distant jet engines overhead.

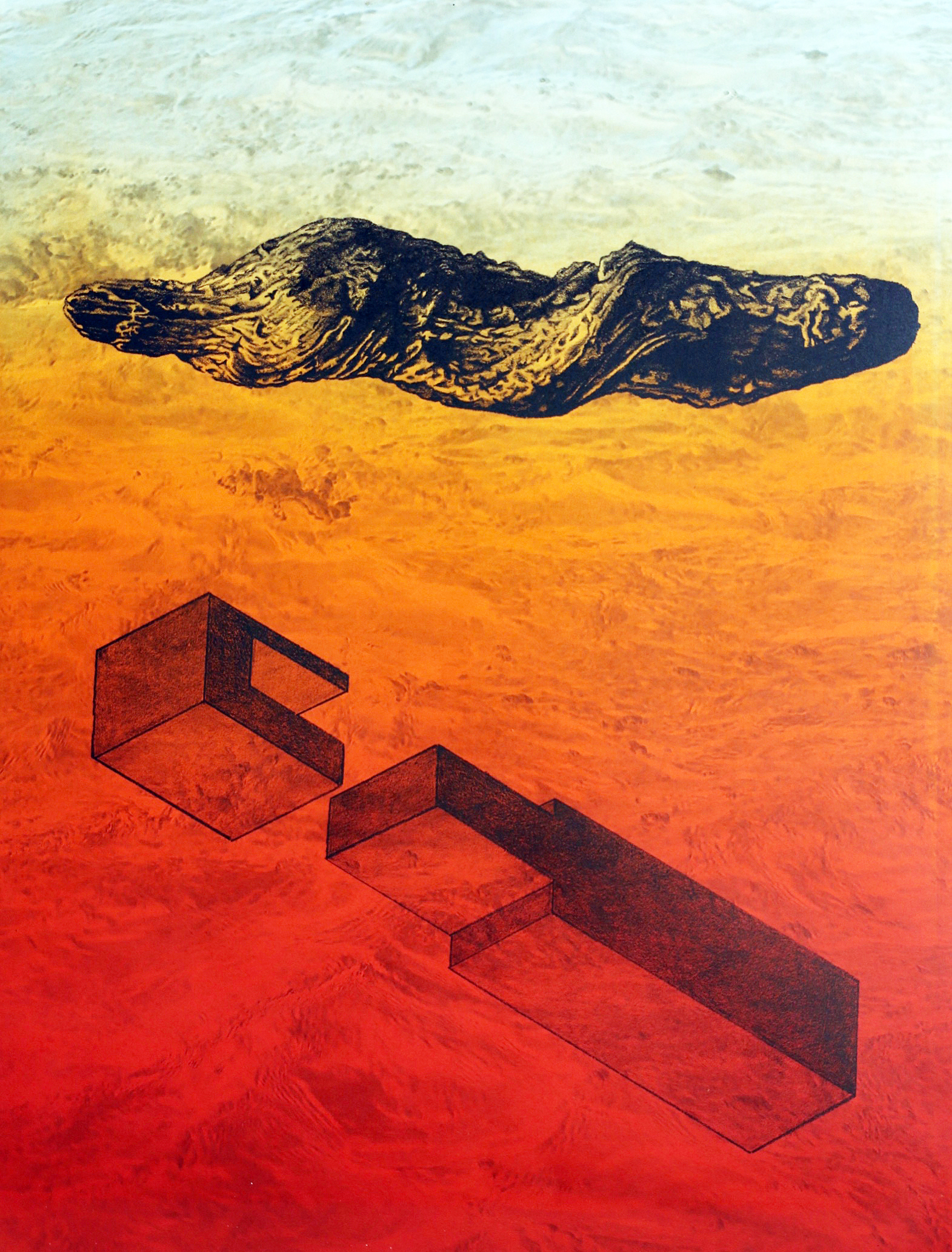

Arron Foster: “Lost in the Sand”, stone lithography, relief, digital inkjet, 22 x 17 inches, 2017

Arron Foster’s Lost in the Sandand Fossil Firealso address a relationship between the manufactured and the natural by way of setting drawn objects resembling smooth cast concrete forms alongside objects resembling a rough tree branch or section of bark. Lost in the Sand, a stone lithograph with relief and inkjet, floats this pairing of opposite sensations above a desert landscape with a transparent haze of color shifting from yellow to orange to red, from the top to the bottom of the piece. It conjures a strong sense of a place without specificity. Similarly, Fossil Fire, a stone lithograph with inkjet, depicts its pair of objects floating over a desert landscape which this time is turned on its side. The light however, remains a pale yellow. Both prints possess a timelessness—objects taken out of time, perhaps archeological remnants of environments lost whether through the collapse of an ecosystem or the fall of a civilization or both. Whether grown or constructed, each has been buried and dug back up. The precision with which each object is rendered with a lithographic crayon, has a studious clarity. The objects are able to crystallize specific, contrasting sensations in the mind. The landscape in each image, however, conjures a non-specific place, a dislocation from time, an environment of reverie where the objects may remain lost to us.

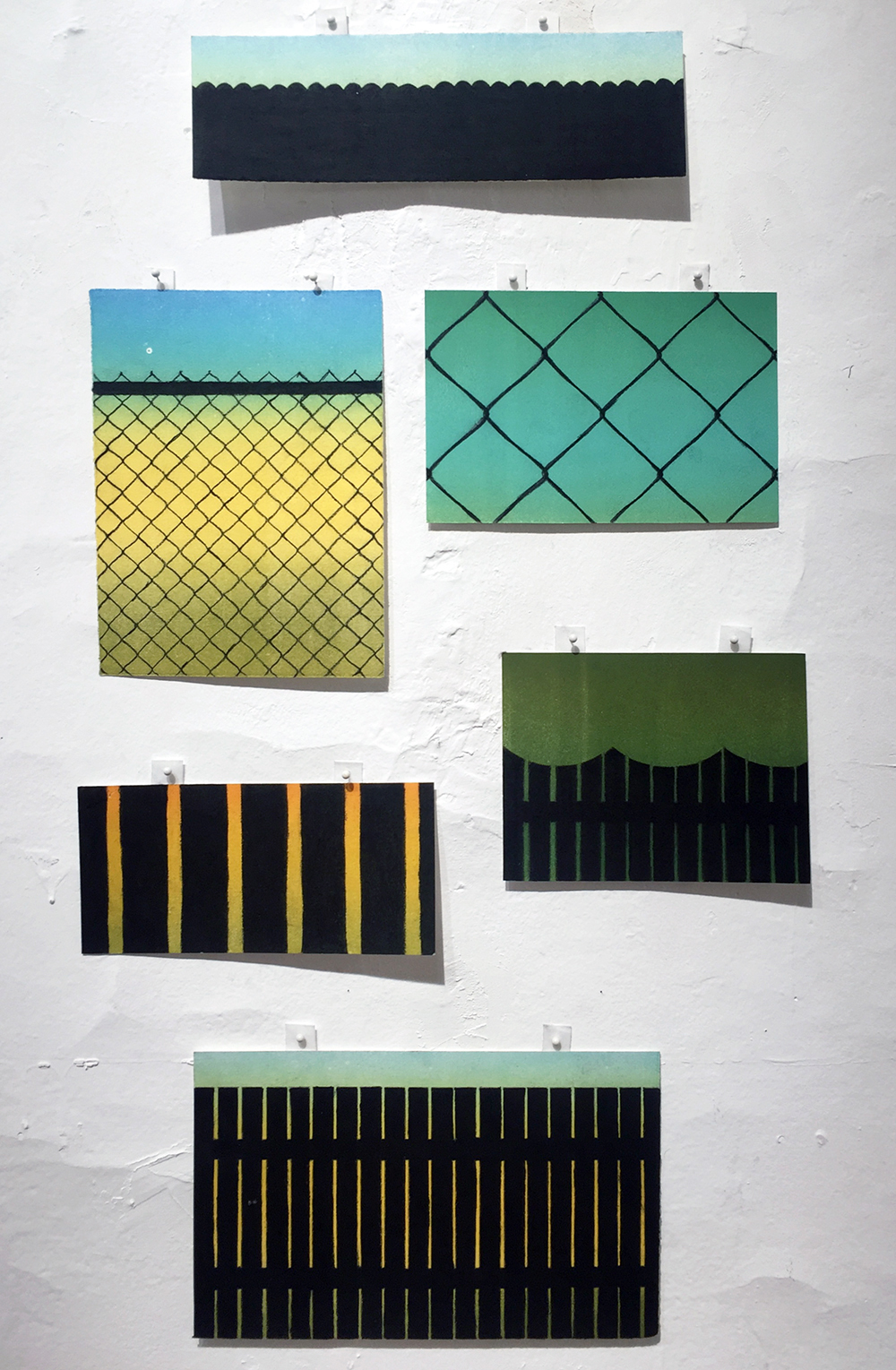

Matthew McLaughlin: “PS_Sample” (counterclockwise: 15, 13, 14, 10, 5, 2), monotype with charcoal drawing, 3 x 10 inches, 2018

Matthew McLaughlin confronts the paradox of the planned community. In PS_Sample (numbered variously 2, 5, 10, 13, 14, 15), a series of six monotypes with charcoal drawing, and with an untitled installation comprised of printed and cut wood relief fragments assembled into an image, he delves into the poetics of fencing. Specifically, the image of the suburban backyard fence. The PS_Sample configuration presents six different samples or sections of a fence type. The PS in the title refers to “Personal Space,” and McLaughlin creates a space that is about imposition—the imposition of the fence on the landscape to disconnect the view from the viewer. The fence becomes a blockage, an interruption, another act of dislocation as the ambiguous, sublime color field of the monotyped background, with its alluring half-light, is divided and obscured by the dark silhouette of the fencing. This is the establishment of a personal space, but at the risk of distorting a view to the outside. Each is a window into a landscape that denies access to that landscape. Are those of us behind the fence imprisoned or protected or both? The space of the images is intentionally ambiguous.

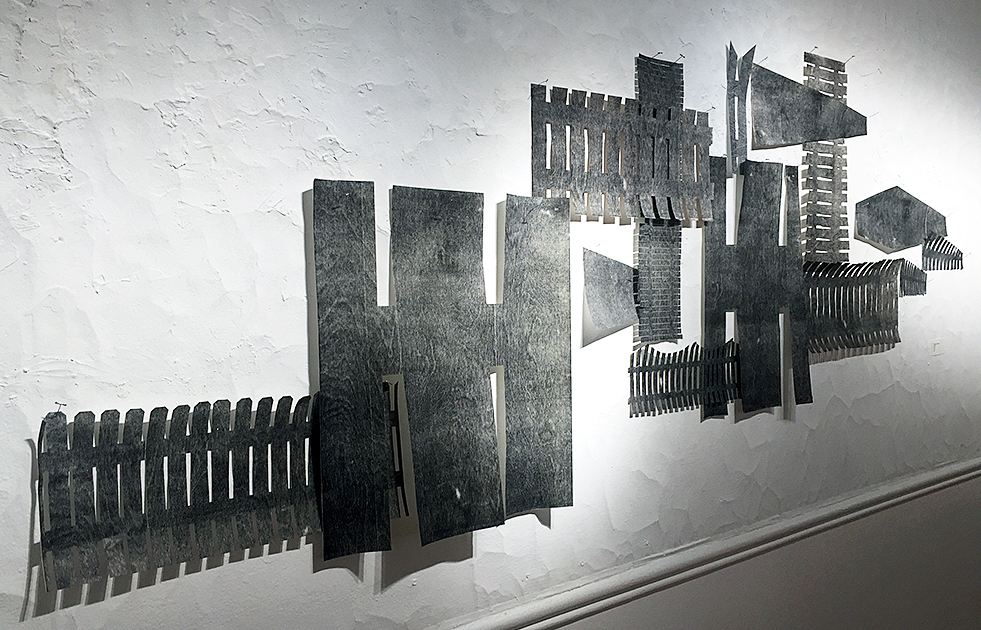

Matthew McLaughlin: “Untitled”, wall installation, monoprint on cut paper, variable dimensions, 2019

With his Untitled installation, we are given another fence—this time a series of deconstructed fences and barriers, reassembled via collage into a single ragtag barrier stretched across the gallery wall. The single unifying element beyond the overlap of its individual sections, is that of its printed woodgrain. But the reality of the cut paper fragments pinned together, with the shapes drooping and wavering here and there, is the impression of a hasty fortification. But against what? Who is keeping whom out, and for what purpose? What is personal space in the context of community? How do you integrate and separate yourself simultaneously?

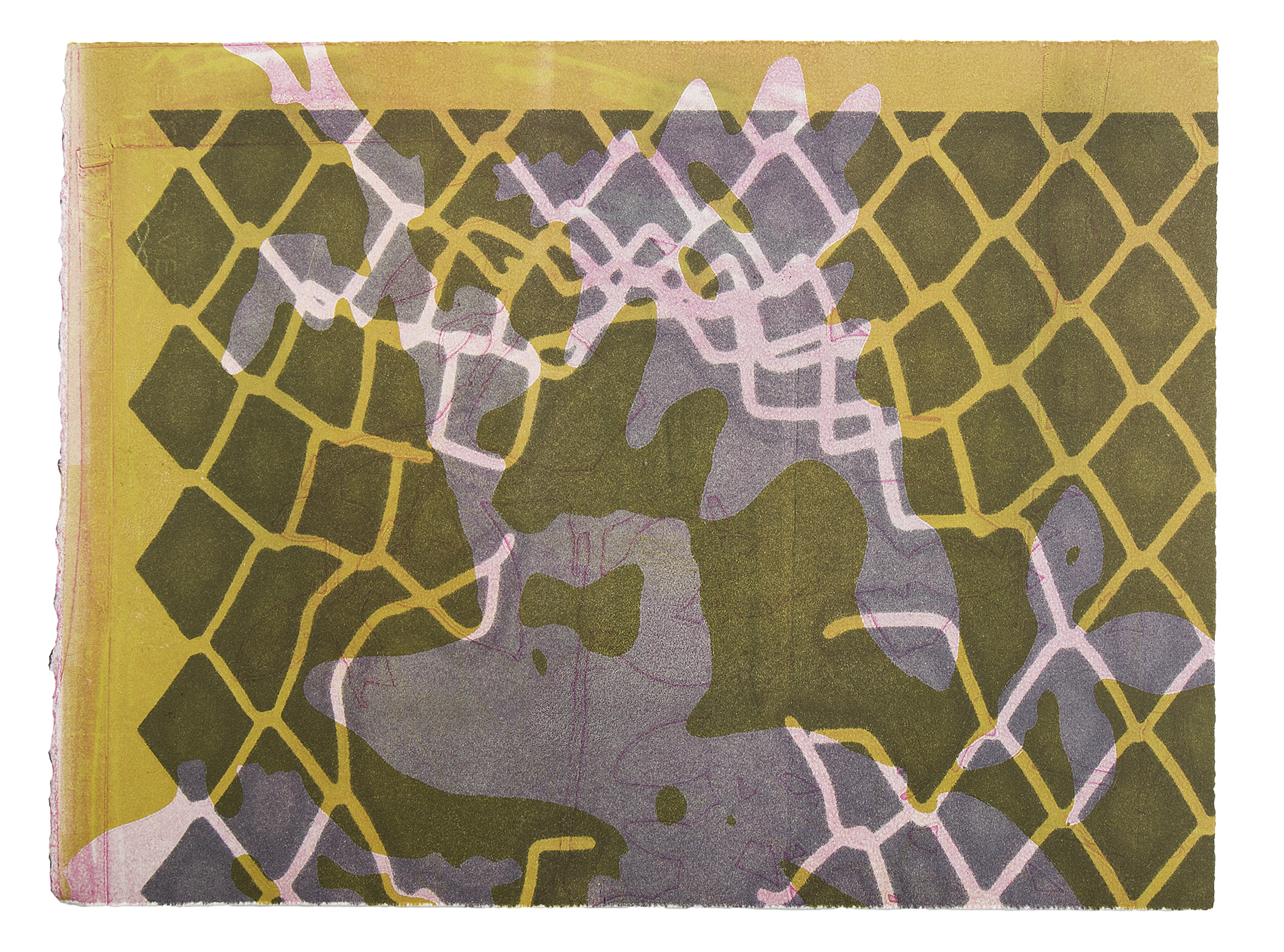

Taryn McMahon: “Massive Barrier”, monoprint, 14 x 18 inches, 2017

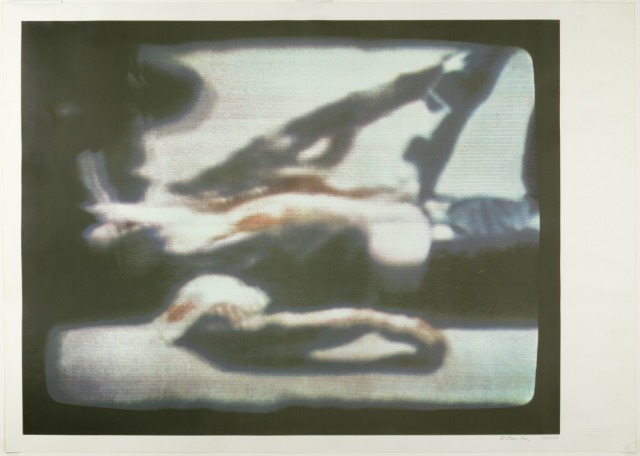

Taryn McMahon employs a layering of color and form in a series of monotypes in the exhibition, whereby the process of printmaking as an act of image projection addresses how we construct our relationship with the natural world. In Rising Water, Distant Garden, Massive Barrier and Wall, McMahon fragments and disrupts our depth of vision as a means to complicate how we are viewing her work. What can appear at first as deceptively simple visual texture and pattern existing on a shallow plane opens up and gives way to a slippage of foreground and background. Each image is a landscape. What we are experiencing is not clear at first and we must navigate our way into the space of the composition, finding our place as it were. The work demands that we enter it. The colors are not insistent, but are suggestive. These are highly atmospheric works that quietly intrude on consciousness. The layers vibrant between negative and positive space, light and shadow, heaviness and weightlessness. We are both inside and outside of these images. Their apparent flatness at first glance, gives way to an unfolding of space as more time is spent with each work. They are a fascinating conundrum: consisting of barriers that open up. This is perhaps a conceptual reversal of how we mediate the natural world: we tend toward flattening it, cutting it up, boxing it in, imposing our will upon it when we image it with our shallow depth of vision. And yet, we also see the natural world as boundless, infinite in its ability to surround us. The truth however is more complicated. As we are bound to our environment, the way in which we perceive it will determine its existence.

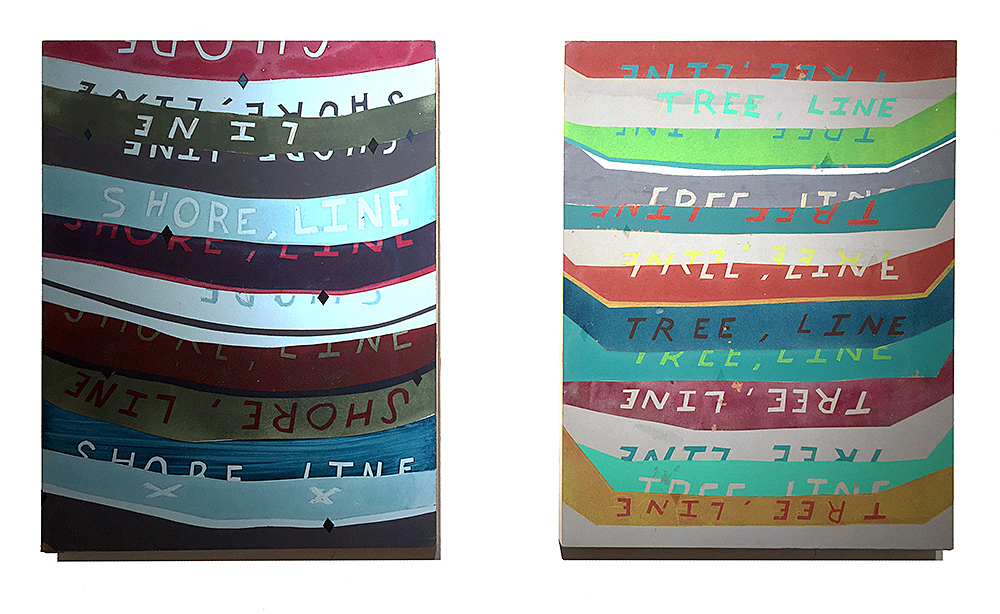

Nick Satinover : “ Northwoods Suite ( 4 ) ” and “Northwoods Suite ( 3 )”, both screen print and drawing on panel, 12 x 18 inches each, 2013

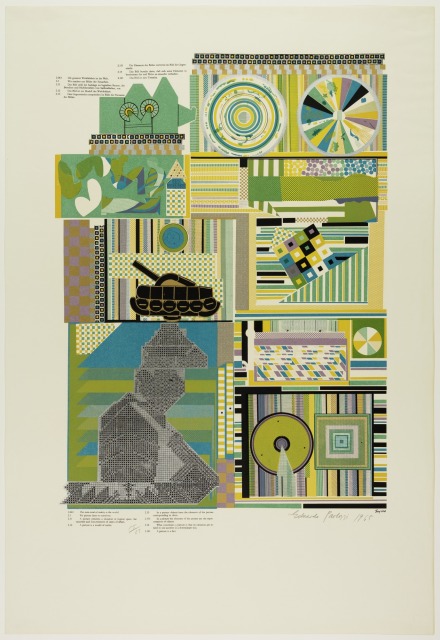

With Northwoods Suite (4) and (3), both screen print and drawing on panel, Nick Satinover is concerned with the poetics of place via half remembered maps and diagrams, the vernacular of hand-painted roadside signs and midcentury children’s educational books. There is something satisfying in the instructive playfulness of Satinover’s images. A warmth emanates from the work as he pairs abstraction with playfulness. The works are familiar without being specific. These are maps and diagrams, but only in the most suggestive sense. If maps and diagrams are about anchoring knowledge, Satinover does something wondrous by loosening their didactic boundaries so that we are given a poetic variation on mapping. The works summon the memory of early learning minus the demands of teaching. A child-like universality is on display: we are locating ourselves in someplace that could be anyplace. Place names and lines of demarcation soften and become gestural. Zones of information become pure passages of shape and color. He constructs a memory space. An evocation of discovering place for the first time.

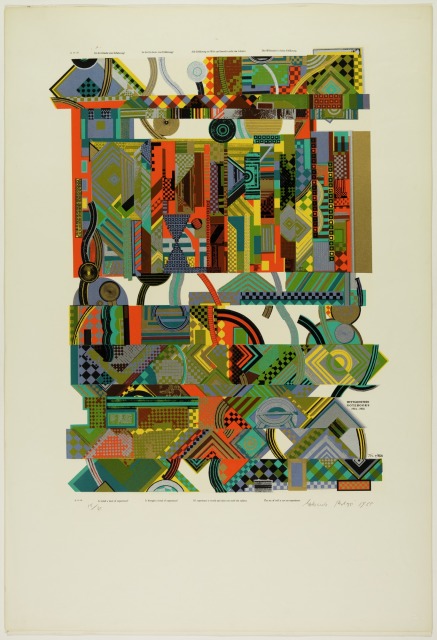

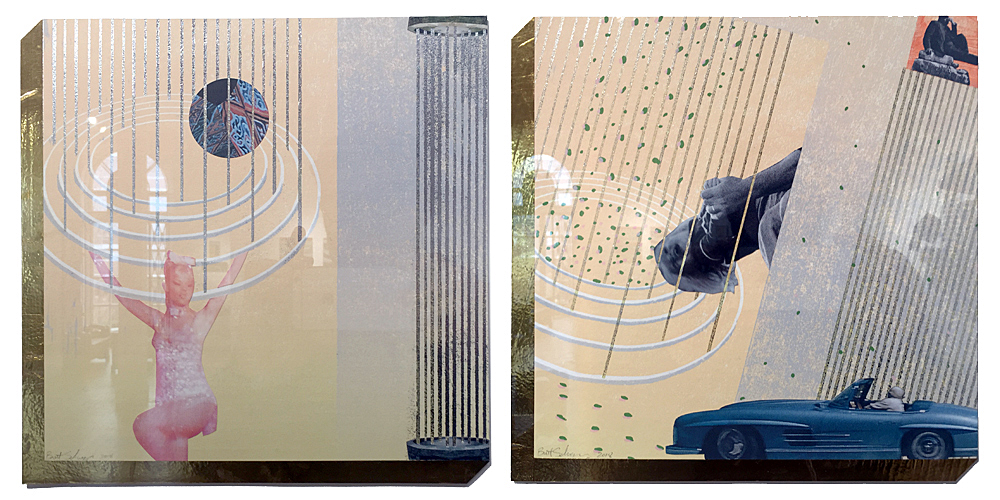

Brett Schieszer: “Head on Backwards, Feet at Funny Angles” and “Smile Before You Want To”, both reductive woodcut, screen print, lithography and digital collage with foil, 10 x 10 inches each, 2018

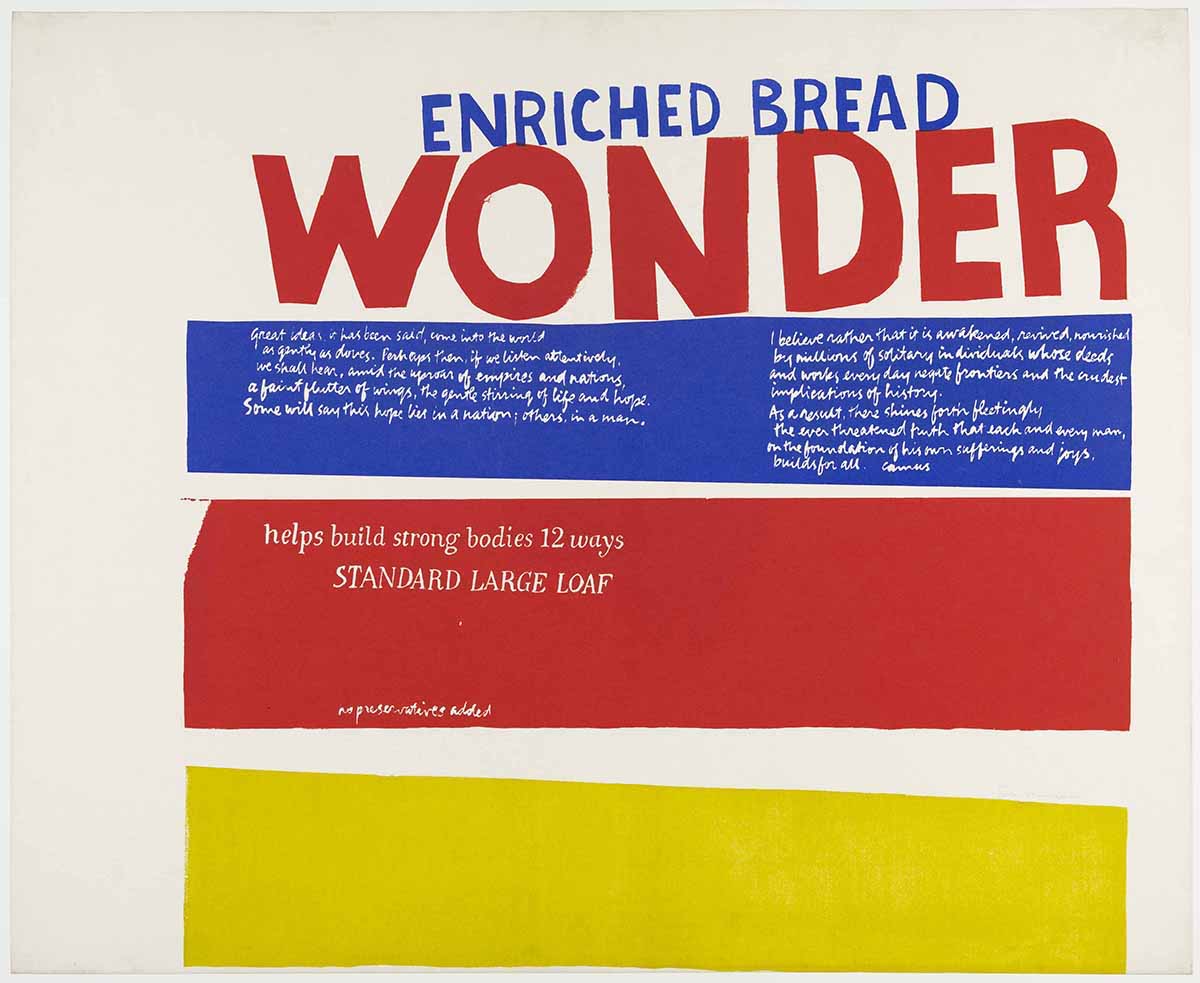

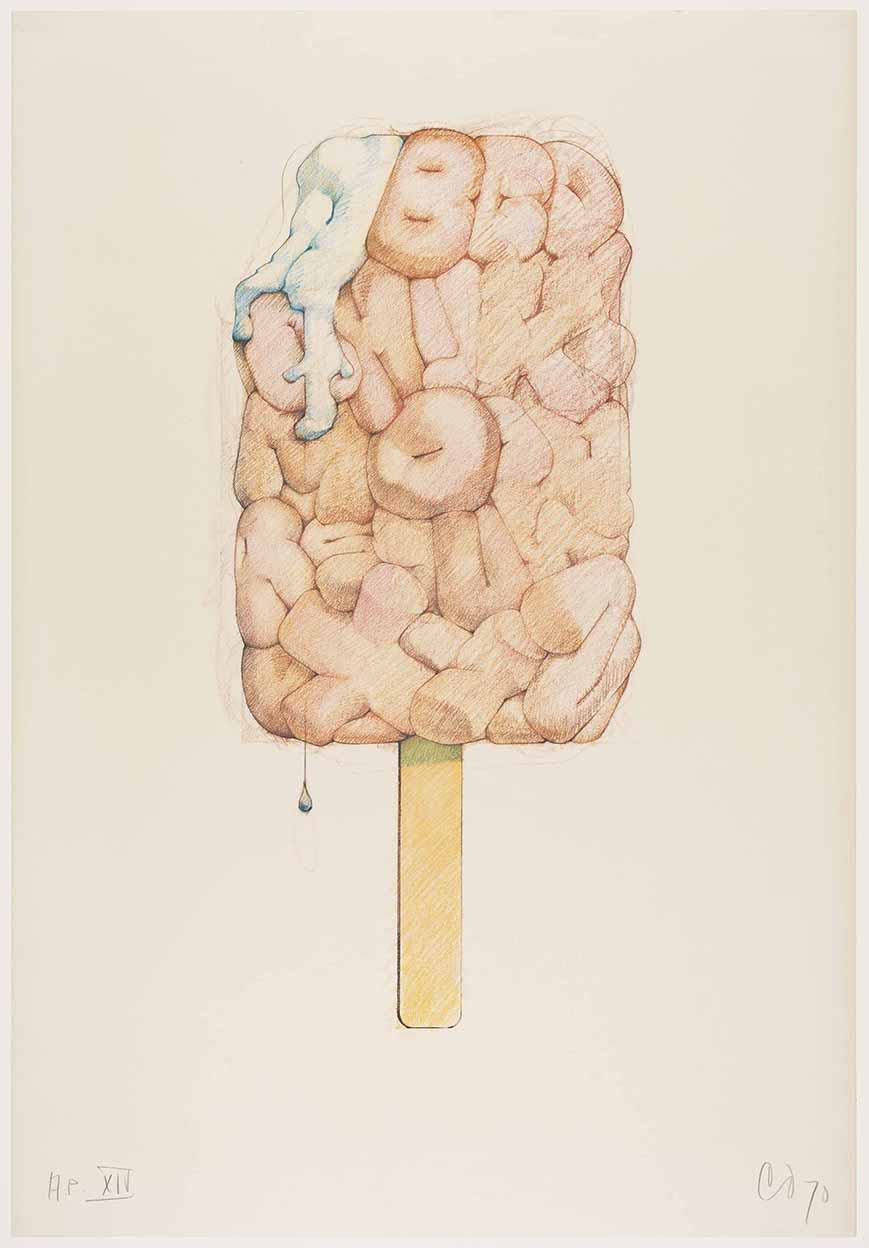

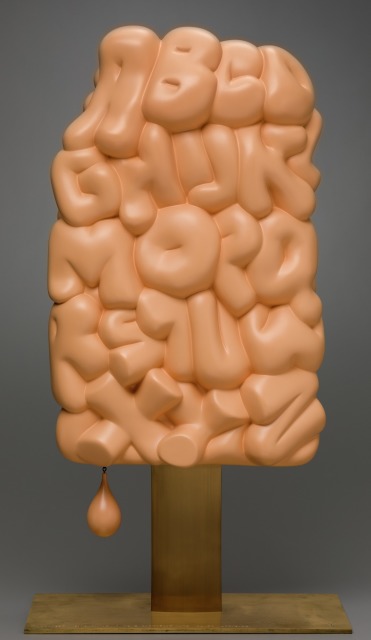

The work of Brett Schieszer seems to emerge from memory as well. The memory of expectation. In Head on Backwards, Feet at Funny Angles, Smile Before You Want To, and Really There is No Need, It’s Fine, each made with an amalgam of reductive woodcut, screen print, lithography, digital collage and foil, we are shown dynamic, bright, seemingly optimistic constructions, that conjure Russian Constructivist propaganda collages from the late 1920’s, such as those by artist Gustav Klutsis (1895-1938), as well as mid-century American advertising, both harnessing an optimism to promote a belief system and a lifestyle. For Schieszer, the past is a landscape, as the glossy surfaces, glowing colors, and radiant patterns of his images beckon entry into a dreamscape, a vacationland of the mind fueled by nostalgia. And yet, these are impossible places. Their unreality heightened by cutout photographic figuration placed against open expanses of color. Dreamland is nowhere. It is an imaginary space. Schieszer’s titles even have contradiction baked into them: a head is on backwards, feet are at funny angles. The natural act of smiling is something done before you want to. There is the false reassurance that everything is fine, and no other need should be considered. The images are each bordered on two edges by gold foil with a perspective that lends a false thickness to the composition. It is as if these are panels, tiles, or thick postcards projecting outward, persuading a visitation to this place where things seem to be alright.

Collectively, all of the work in “Compo/Site” shuttles between abstraction and representation and suggest a split, a perceptual struggle between the concrete recognition of place and the effects of our fleeting personal impressions and projections upon it. That print is the primary vehicle for such an exploration is not without reason. As a process predicated on projection and memory—the transference of an image from one surface to another for the sake of creating an impression—there is much resonance between medium and subject here. Recording a mark on a surface, fixing it, is akin to the physical and mental marks we impose on the environments we inhabit or pass through. The history of mapping has been the history of print. To devise a system for spatial demarcation on a landscape in order to navigate it, possess it, name it, is also a form of psychological mapping. We construct the world as we wish it to be by projecting our identity upon it. In essence, we are constructing by compositing—merging the real and the unreal, the past and the present, the natural and the manufactured, the meaningful and the meaningless—resulting in a boundless psycho-geographic container whose definition is elastic and ultimately incapable of being colonized in any state of permanence.

Scarab Club exhibition “Compo / Site” through May 18th, 2019