John Corbin’s exhibition: Level and Plumb

“In the last several years the Monarch’s (butterflies) population has decreased for some known (logging in Mexico) and some unknown reasons. It might be that the Monarch has been rendered obsolete. I haven’t found the app that replaced it yet.” – John Corbin, Some Thoughts about My Work and Becoming Obsolete

John Corbin’s solo exhibition Level and Plumb, which opened at Susanne Hilberry Gallery on June 10, is a deconstructed, re-assembled encyclopedia of romantic obsolescence. The visually discordant pairings of Corbin’s sculptures, composed of found clocks and carpenter’s levels, and his collages of dissected atlas maps, instantly provoke curiosity and invite closer analysis. These parallel bodies of work gradually break down into a bizarre, insightful history of the chronology of both time and space. The objects Corbin uses to explore this history- clocks, carpenter’s levels, printed maps, and globe-trotting migrant birds and butterflies- eulogize the laborious, beautiful process of gaining understanding of the workings of the universe through trial and error, meticulous inch-by-inch progress, and miraculous leaps of logic.

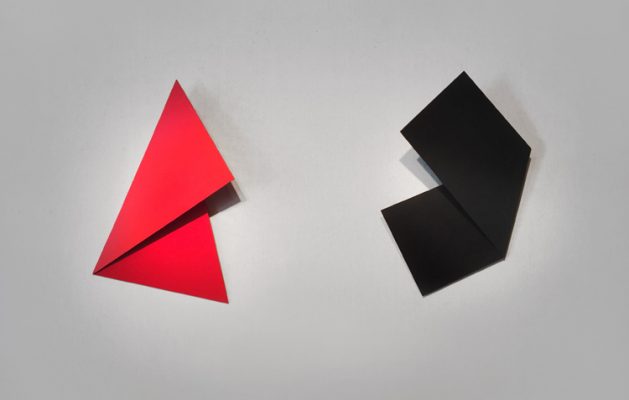

John Corbin, Installation shot – All images courtesy of Angela Pham and Susanne Hilberry

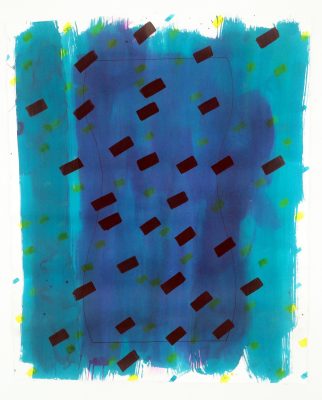

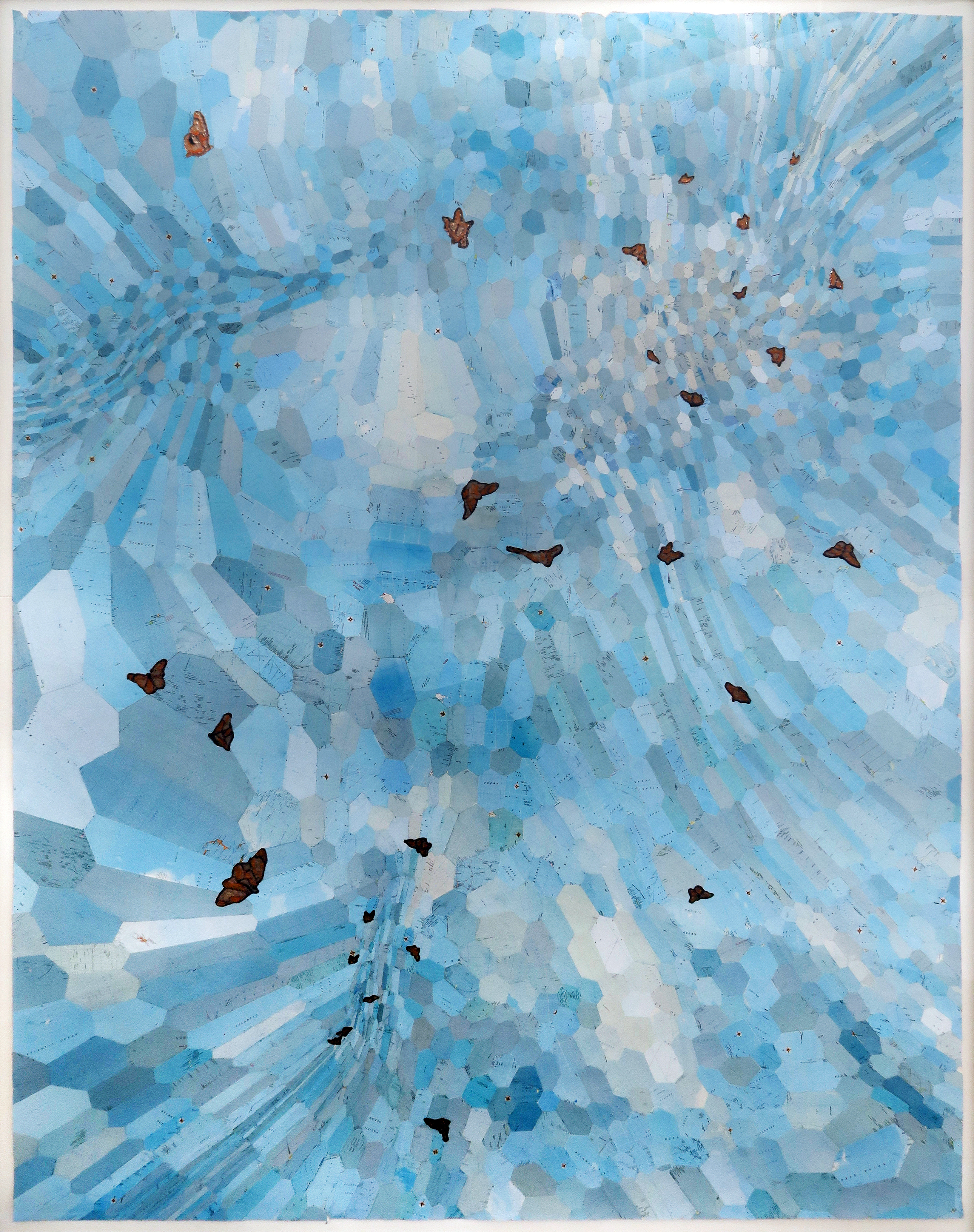

Corbin’s deconstructed map collages, both intimately and massively scaled, are beautiful objects in and of themselves- the honeycomb-like patterns and delicate tonal grades that deconstruct atlas maps into swirling, undulating atmospheric studies traversed by iconic migratory creatures- cranes, monarch butterflies- speak both to the original function of these objects- to cast sublime amounts of space into understandable terms for people- and to their total functional obsolescence now- an abundant natural resource for repurposing into studio practice.

John Corbin, Two if by Sea, 2012-16 Acrylic Map collage – 68in x 88in

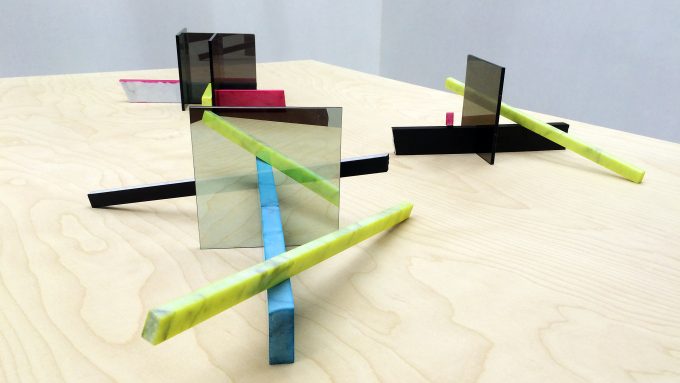

The same feeling comes through in Corbin’s sculpture- the assemblages of levels and clocks begin to communicate their quaint insistence on the perfect right angle, the perfect orb, hard-wired to the wall, veiled in white. They’re no longer tactile tools, but studies in contemplation of the universal truths that they are indexical to.

John Corbin, 3 Spirit Level III 2016 Levels and Hourglasses 11.5in x 20in x 1 and one quarter inch

One word that comes repeatedly to mind while exploring Corbin’s show is ephemera. The masses of printed information and measuring, calibrating objects that, not so long ago, were as essential to us as our thumbs. As one delves deeper into Level and Plumb, the realization gradually dawns that the source materials that make up all of the works in the show bear an uncannily simultaneous familiarity and distance. Where have these tactile measuring tools- clocks, levels, puzzles, maps- disappeared to? When did they leave us? Why are they simply no longer a part of our lives? Seen in this light, Corbin’s sculptures and collages begin to read like effigies, and in his statement for Level and Plumb he places the blame for the vanishing of these miraculous objects squarely upon Apple Inc. The huge scale of this leap- timepieces, maps, measuring tools, means of communication, means of documentation, all pouring into one handheld electronic device, bears the same sublime quality as a bound atlas that lays the whole world out before your eyes. It captures the frisson that accompanied one’s first realization that a clock that measured the hours in a day was also documenting the movements of the sun and stars. The compression and deconstruction Corbin subjects his source materials to echoes, as well, the bizarre compression of millennia of human development into ever smaller and more disposable projections of our most inspired leaps of understanding. There’s a tragedy whispering alongside the uncanniness of Corbin’s work- is it not a little sad that these tools, once so essential to our navigation of our world, now take up residence in the stillness of gallery space, as functionally ambiguous to culture as any other work of fine art?

John Corbin, Installation image

Are the gallery and the museum now the storehouses for the dictation from the stars that once sparked our highest aspirations that we’re not sure what to do with anymore? What is the relationship of those aspirations to the objects we hold in our hands today? Though conspicuously absent visually, the iPhone is a constant, silent presence in Level and Plumb, appearing in ironic relief in your own hands every few seconds to check the time or take a picture, insisting on its appropriation of the delicate structures of time and space that Corbin’s materials used to hold the keys to. Level and Plumb is an important, and timely show, in the way it quietly and beautifully reveals the evolution (or possibly devolution) of human mastery of the discernable world to us. The ephemeral tools we used to rely on to gauge the world around us may seem unwieldy and quaint now, but Corbin’s reworking of them remind us that they were beautiful. They sang of the universe. And, even removed from practical use and deconstructed, they still carry insights that make the most user-friendly smartphone suddenly feel blunter than a flint hand-axe.

Level and Plumb is on display at Susanne Hilberry Gallery June 10 through August 6, 2016.