Jefferson Pinder – Weapons and White Music, at the Wayne State University’s Elaine Jacob Gallery

Jefferson Pinder, Installation image, Colored Entrance, 2017

In a lecture given a few years ago, Jefferson Pinder opened by speaking about two luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance: sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, who believed the only worthwhile art a Black artist could make was propaganda that advanced the cause of social justice; and philosopher Alain Locke, who believed Black artists needed the freedom to, as Locke’s biographer Jeffrey C. Stewart puts it, “produce a black subjectivity that could become the agent of a cultural and social revolution.” Weapons and White Music, a compact anthology of Pinder’s art from the last decade or so, on view at Wayne State University’s Elaine Jacob Gallery now through April 27, showcases a body of work that balances aesthetics and activism. It addresses issues of race not with unequivocal slogans, but in an audio-visual language that prompts contemplation, investigation, and soul-searching. There are no handy wall labels here to coach the visitor, so inevitably the nature of that contemplation will vary from one person to the next.

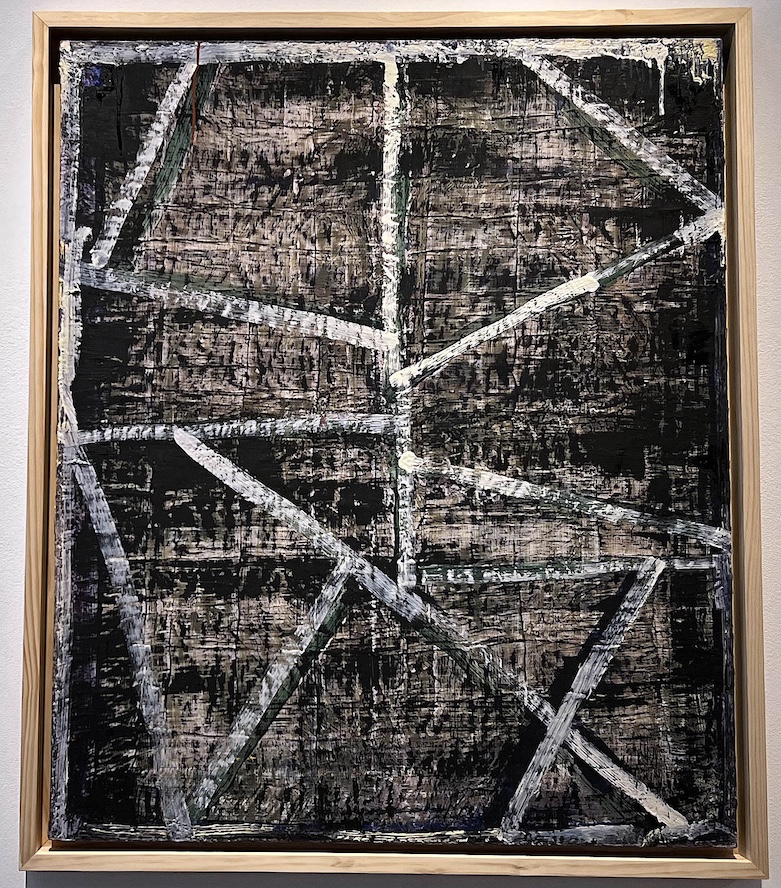

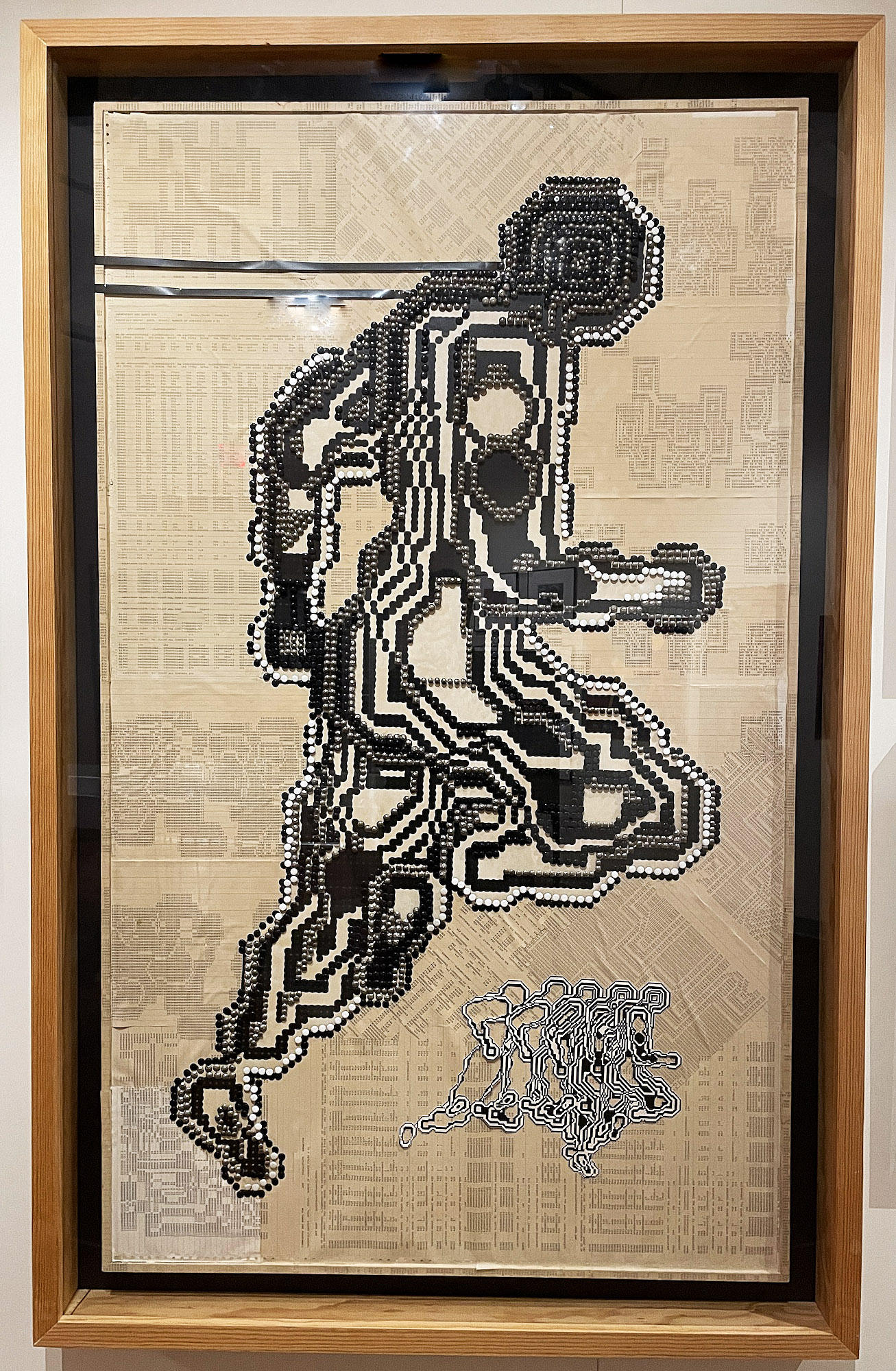

Jefferson Pinder, Bent Spear (after John Brown), 2024

Those averse to violence on principle, for example, might be discomfited by an exhibition that features spears, billy clubs, and Molotov cocktails (never mind that the collection of armor, swords, and firearms in the Great Hall of the nearby Detroit Institute of Arts is one of the museum’s most popular attractions). Some context might help; Bent Spear (after John Brown), a piece comprising a volley of pikes displayed across one wall of the Jacob gallery’s first floor, references weapons once commissioned by the titular white abolitionist, who intended to supply them to freed Black men for use in the uprising he hoped to provoke. The spears here are arrayed behind a vitrine containing the Head of a Man — a human skull with teeth plated in gold. Drawings of a similar skull are superimposed over photos of Black Panther leader Huey Newton in a series of nearby screen prints.

The musical part of the exhibition’s title also appears on the gallery’s first floor. Facing the entrance are five monitors playing a 50-minute loop of videos featuring Black “singers” lip-syncing to a series of songs by white pop-rock bands. Some of the performers onscreen are expressive, some are deadpan, and each takes a different part of the harmonies. Entitled Revival, the piece is described on the artist’s website as a “virtual choir” that “reverses a longstanding tradition of mainstream cultural appropriation.” Some of the songs featured are more mainstream than others, but many share themes of violence that “hit different,” as the kids say, when apparently voiced by Black performers. Consider Born Under Punches by Talking Heads, with its haunted refrain, “all I want is to breathe,” that can’t help evoking Eric Garner’s dying words. (Pinder had incorporated the song into the piece prior to Garner’s killing.) Also featured are Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, about an imprisoned youth facing execution; The Flaming Lips’ The W.A.N.D. — short for “The Will Always Negates Defeat” — which boasts, “I’ve got a tricked-out magic stick that will make them all fall / We’ve got the power now, motherfuckers, that’s where it belongs”; even The Smiths’ Girlfriend In A Coma is included. It’s hard to know what someone unfamiliar with these songs will make of the piece, but for those who know, Revival will cast the music in a different light.

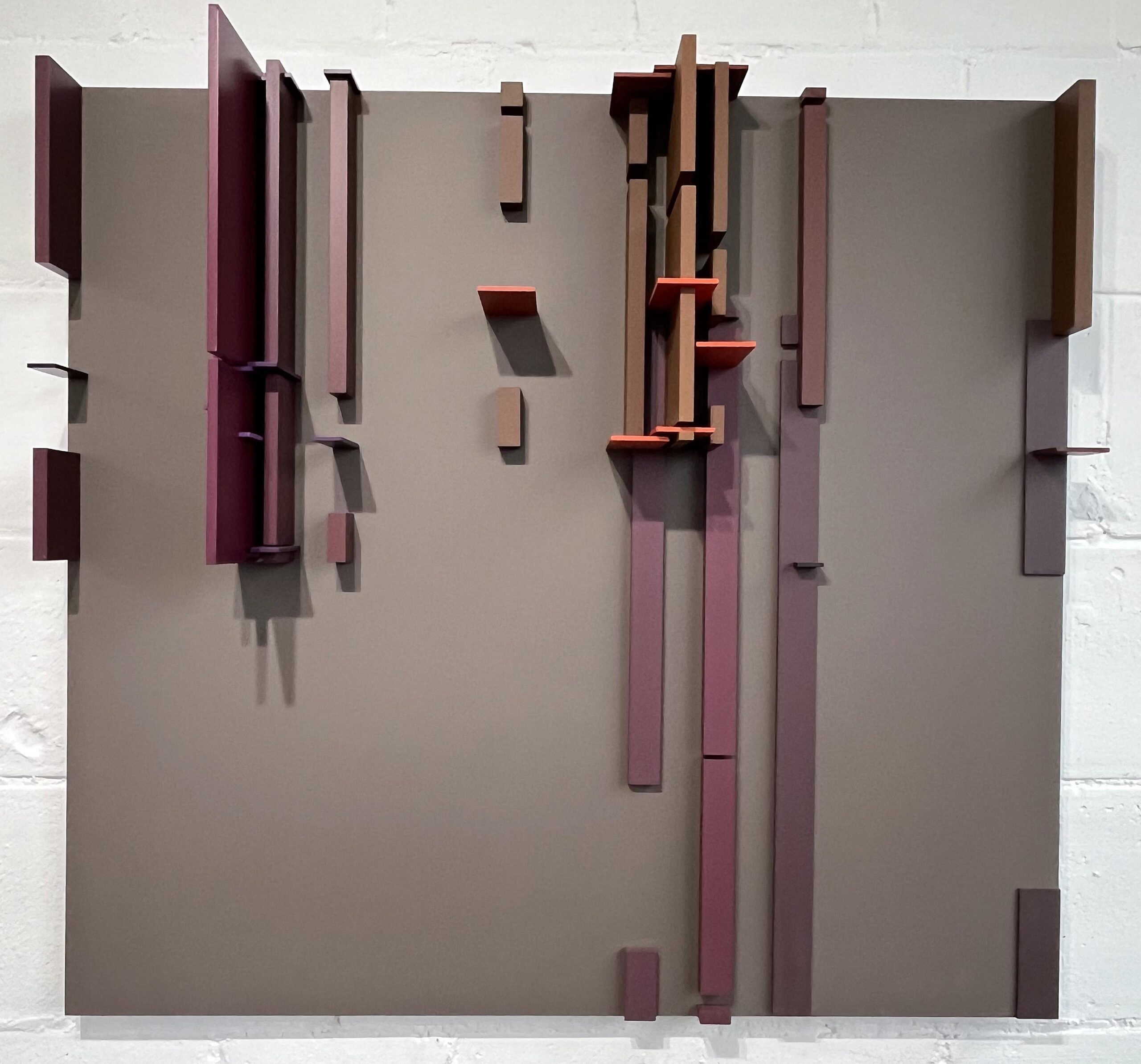

The curving stairway to the gallery’s second floor is cleverly incorporated into the exhibit itself. Toward the bottom of the stairs is a weathered neon sign with a red arrow, that might be from a historical museum’s display about the days of Jim Crow, except that a “d” has been added to turn the phrase “colored entrance” into “colored entranced,” with connotations both of wonder and bewitchment. Hovering above the top of the stairs, where the visitor must pass under it to proceed, is Gauntlet, a menacing cloud of charred billy clubs that threatens to rain harm onto anyone below.

Jefferson Pinder, Fire Next Time, 2021 – Glass bottles, graphite, fabric, matches and catalyst.

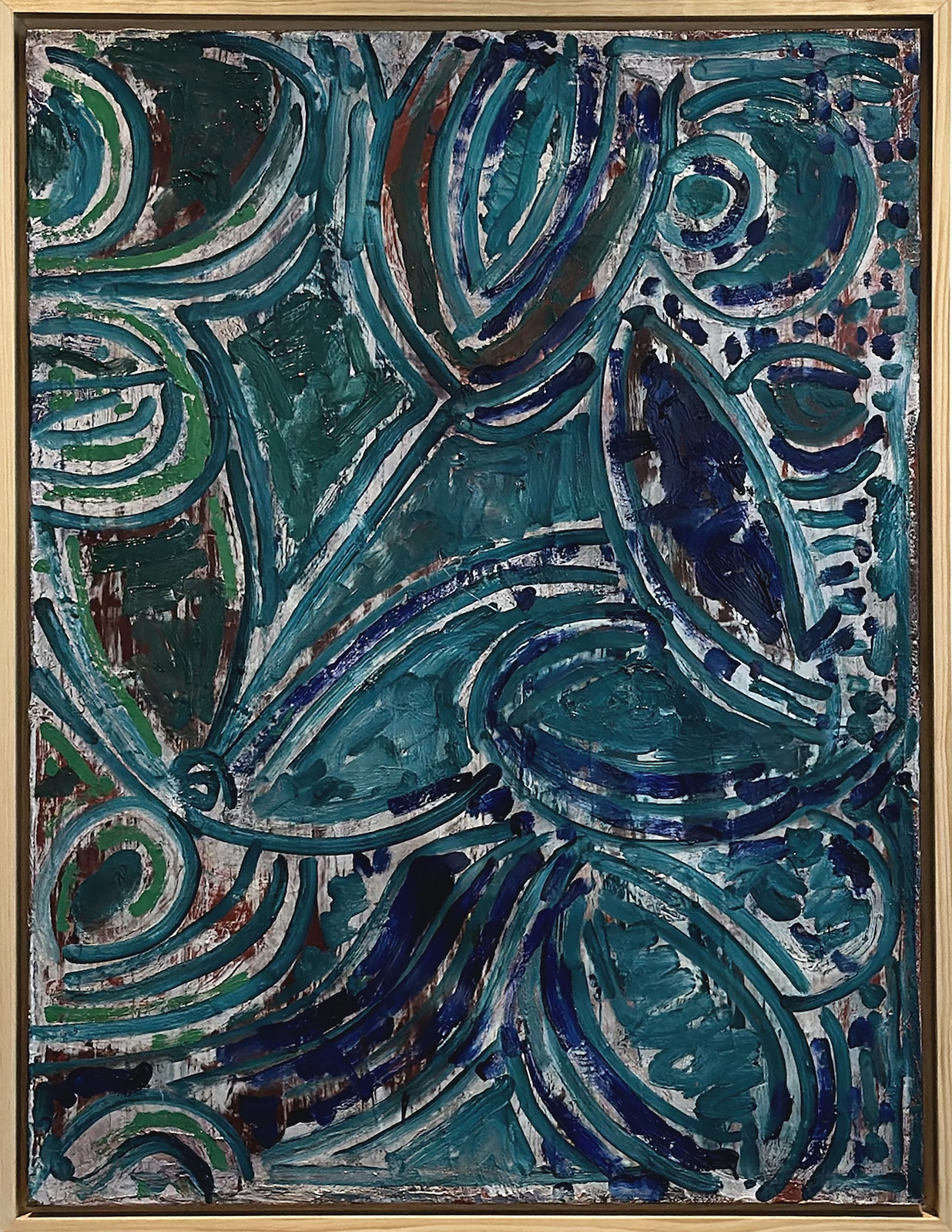

At the top of the stairs is Fire Next Time, a set of four shelves of varying widths arranged in an inverted pyramid, upon which are displayed 25 Molotov cocktails — improvised incendiaries made from bottles, rags, and gasoline, associated with what’s sometimes called irregular warfare. They appear both grubbily utilitarian and oddly compelling in the way weapons often are. Up close, they’re revealed to be adorned with wire, duct tape, packed mud, BBs, matches, hair, shards of glass, and other material. The presentation itself is formal, its ascending shape suggesting escalating conflict or the rising flames themselves.

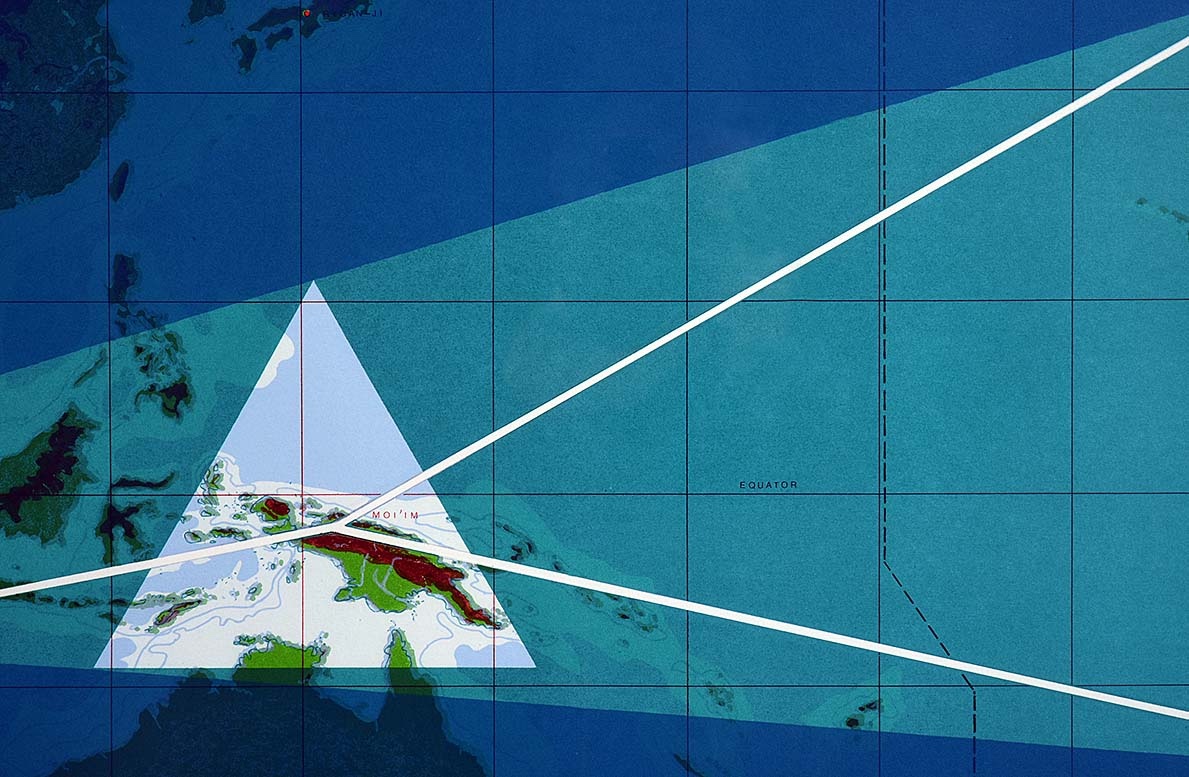

Projected onto a wall on the other side of the gallery is a new work, a video installation called Greatest Hits (violent pun likely intended); it’s a montage of scenes from movies and television programs in which white actors utter the N-word. The films range from earnest dramas (Roots; Do The Right Thing; In The Heat of the Night) and cop flicks (Dirty Harry; The French Connection; Starsky & Hutch), to satire (Blazing Saddles, a notorious Saturday Night Live sketch featuring Chevy Chase and Richard Pryor), broad comedy (Bad News Bears; The Jerk), and more, including the works of Quentin Tarantino, without which no such compilation would be complete. The montage closes with two musical performances: punk godmother Patti Smith belting her 1978 song “Rock & Roll N—,” adding herself to a long line of white artists who have tried to liken themselves to marginalized minorities in an attempt to set themselves apart from mainstream society; and a 1972 episode of The Dick Cavett Show, in which John Lennon and Yoko Ono remark on the abuse of women across the racial spectrum with their song “Woman is the N— of the World.”

Jefferson Pinder, Greatest Hits, 2024 – HD Video (running time:23 Min.

The creators of these films would presumably have justifications for their use of the offensive term, even if it was only for verisimilitude. For viewers familiar with these films, the contexts in which the slur is used will be understood, though not everyone will accept the justifications for its use from one film to the next, or at all. To anyone unfamiliar with them, the piece may not be much more than a litany of hate speech being ejected from anonymous white mouths. Throughout, though, there are intriguing juxtapositions within the montage, such as that of a scene from the Civil War drama Glorymashed up against one from Kubrick’s Vietnam picture Full Metal Jacket, drawing a line between the two conflicts. A theme emerges of white anti-heroes excusing their racism with the claim that they hate everybody equally. And while it’s unclear how Beastie Boys’ song “Sure Shot” relates to the scenes from The Jerk and Roots over which it’s played, putting The Moody Blues’ “Nights In White Satin” over a clip featuring Ku Klux Klan “knights” from Birth Of A Nation makes for a jarring audiovisual pun.