50th Annual Photography Exhibition at the Scarab Club

Installation view, 50th Annual Scarab Club Photography Exhibition, Installation photo by Christopher Gene, all other photos courtesy of Scarab Club

A striking and expansive display of photographic sensibilities, currently on view in the 50th Annual Scarab Club Photography Exhibition, continues a long-standing tradition of welcoming and introducing current photographic practice. Juried by Ralph Jones, Detroit photographer, documentarian, educator, mentor, and exhibiting artist, this “unthemed” show (as per the Club’s Call for Entry application) is visually vibrant and emotionally rich. The spacious installation of the submissions of 38 artists enhances a diverse array of figurative and abstract images, formats both commandingly large and gem-like in scale, and bold, colorful pictures in tandem with austerely black and white compositions.

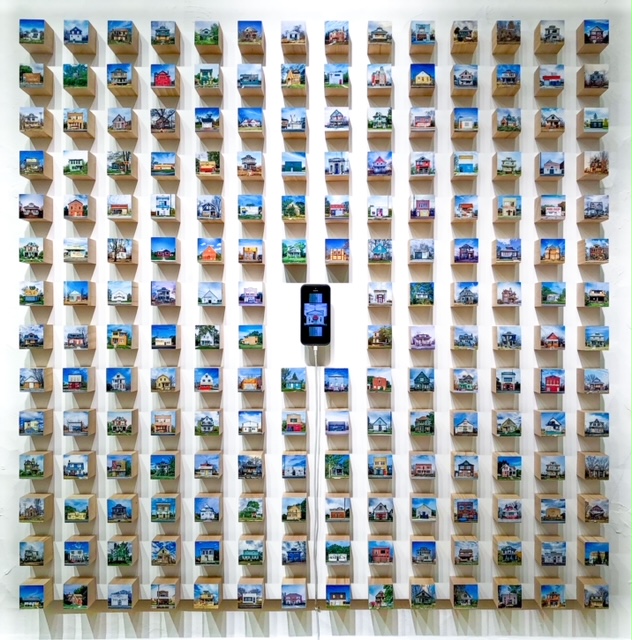

Technically, Matthew Raupp’s Detroit Photo Series (2020) might be termed a relief, projecting as it does some three inches plus from the wall. His compendium of 192 colorful, miniature views of buildings (2 x 2” each) represent sharply focused, frontal images of structures drawn from the precincts of Detroit. Each is individually mounted on a 2 “ wood cube imbuing them with the weight and heft of a three-dimensional structure. Fronts of houses, storefronts, banks, churches, and fire stations in various states of repair–intact, rehabbed, repurposed, or derelict– attest to the adaptability and resiliency of The D. Additionally, an iPhone mounted dead center zooms through the entire ensemble of facades, offering an alternative, fast-paced scan (so 21st century) through Raupp’s personal land bank.

Matthew Raupp, Detroit Photo Series, 48 x 48 x 3,” Wood blocks, photographic prints, iPhone

Detail, Matthew Raupp, Detroit Photo Series

Two vertical compositions, rather like exclamation points, punctuate one wall, making the most of the slender height of the format. In Kate Gowman’s five feet tall Scrapyard Fire (2012), no flames are in sight. Instead, a hazy atmosphere pervades the scene. The smoggy smoke of the fire, some distance away, merges with the gray, shapeshifting clouds and gracefully listing tree trunks, while two men quietly inhabit the crisply detailed foreground, one perched atop a wrecked car and the other standing nearby, while gazing toward the unseen fire. Aesthetically, the subtle tonalist merging of gray hues belies the alarming import of Gowman’s title. In contrast, Vincent Cervantez’s poignant The Unveiling (2021), a three feet tall still life of a white bridal(?) veil sprawled on a bed of brown, parched leaves, evokes loss, accidental or deliberate, perhaps a dream forsook, or even a violent encounter. Discarded objects and litter–masks, plastic bags and containers, whippets, and etc.–pervade the culture. Here, rather affectingly, an eddy of wind lifts the veil and threatens to whisk it out of sight.

Kate Gowman, Scrapyard Fire, 60 x 36,” Fine art print on Hahnemuhle paper

Vincent Cervantez, The Unveiling, 36 x 24,” Digital print

Affirmation rules as well in the Scarab Club’s 50th anniversary show. Tom Stoye’s Leap of Farith (2016) presents a silhouetted figure, legs spread wide (the print is 32” broad), head skimming the top of the frame, bounding through a spray of water. Its lithe, explosive energy swiftly transports the viewer aloft and across the expanse of paper. The small, square, quiescent People in a Pandemic (2020), by Anne Knight Weber, however, features four clustered, stationary figures (one adult and three children) on a vast beach as avatars of the endemic isolation of a pandemic. Sans a frame, water, wet sand, reflections, and azure sky shimmer and float free of the gallery wall heightening the glassy stasis of the scene.

Tom Stoye, Leap of Faith, 21 x 32,” Photographic print

Anne Knight Weber, People in a Pandemic, 11 x 11,” Photograph, acrylic glass

Other photographers focus upon the uneasy balance and oft tense interaction between figuration and abstraction. An emphatic zig zaging line rivets the view of Jerry Basierbe’s Steel Breakwater #3–Point Betsie, MI (2019), while in Hats(2016) by David Clements a swirling orange oval governs the foreground. In the former, the dark, zig zagging line of the breakwater thrusts the viewer into the silky, placid waters of Lake Michigan, a coastal locale frequented by the artist. It’s a harsh, slicing armature that connotes something of the blunt force of industrialization. In the latter, Clements presents a vignette drawn from his ongoing series documenting African American church services. Here, the elliptical orange confection up front instantly captures the viewer’s eye before noting another woman, also attired in a matching, eye-catching hat and coat, seated in the next pew forward.

Jerry Basierbe, Steel Breakwater #3–Point Betsie, MI, 18 x 18,” Digital photographic print

David Clements, Hats, 14 x 16,” Photograph

One of the smallest works in the exhibition also touches on fashion. Teresa Petersen’s Fashion for Women and Children (2018), a mere 3 x 3,” presents a fenced off storefront featuring pink and blue pastel raiment for women and children. Like Raupp, Basierbe, Clements, and others, she too scours particular locales for definitive subjects. Alas, here the fashions on parade are imprisoned behind a metal grate, teasingly short-circuiting a window shopper’s desires.

Teresa Petersen, Fashion for Women and Children, 3 x 3,” Photograph

Small, medium, or large, splendidly hued or chastely black and white, figurative or abstract, these singular examples may indeed spur a desire to encounter more of the photographs on display. And that is exactly what this golden anniversary exhibition at the Scarab Club proffers: all 38 selections remain on view through June 26, 2021.

The Scarab Club is located at 217 Farnsworth St. across the street from the Detroit Institute of Arts.