A New State of Matter: Contemporary Glass at the At the Grand Rapids Art Museum

Norwood Viviano (American, b. 1972). Recasting Detroit, 2017. Kilncast glass, 3D printed pattern, and found object, 16.5” x 13.5” x 11”. Photo: Tim Thayer/Robert Hensleigh

Glass defies definition; it’s neither liquid nor solid, and as such it’s been described by physicists as “a new state of mater.” At the Grand Rapids Art Museum (GRAM), a visually dazzling exhibit of glass art makes the point that skilled artists can make this enigmatic mater look like pretty much anything. Glass, A New State of Matter comprises work by an international body of nineteen artists who skillfully manipulate glass in concert with a diverse array of other media: wood, plants, and even uranium. The first major exhibition of glass art in the GRAM’s history, the show highlights the stunning versatility of glass, and however it’s used and in whatever form it assumes, the beauty of the physicality of the glass itself is always paramount.

Glass is an ancient substance, dating back to the ancient Egyptians of about 3,000 BC, but the overwhelming majority of the works on view are emphatically modern, and many were created with the aid of emerging technologies. An ensemble of works by Norwood Viviano applies 3D printing in glass to render cityscapes of actual cities which also allude to their respective histories. A 3D rendered map of Detroit, ground zero of the auto industry, has as its foundation a cast-glass automobile engine block. And a map of Grand Rapids, bisected by the Grand River, rests atop a wooden table, an appropriate emblem for a city known for its historic 20th Century contributions to the furniture industry.

Norwood Viviano (American, b. 1972). Recasting Grand Rapids, 2020. Kilncast glass, 3D printed pattern, and found object, 22 x 17 x 29 ½ inches. Photo: Tim Thayer/Robert Hensleigh

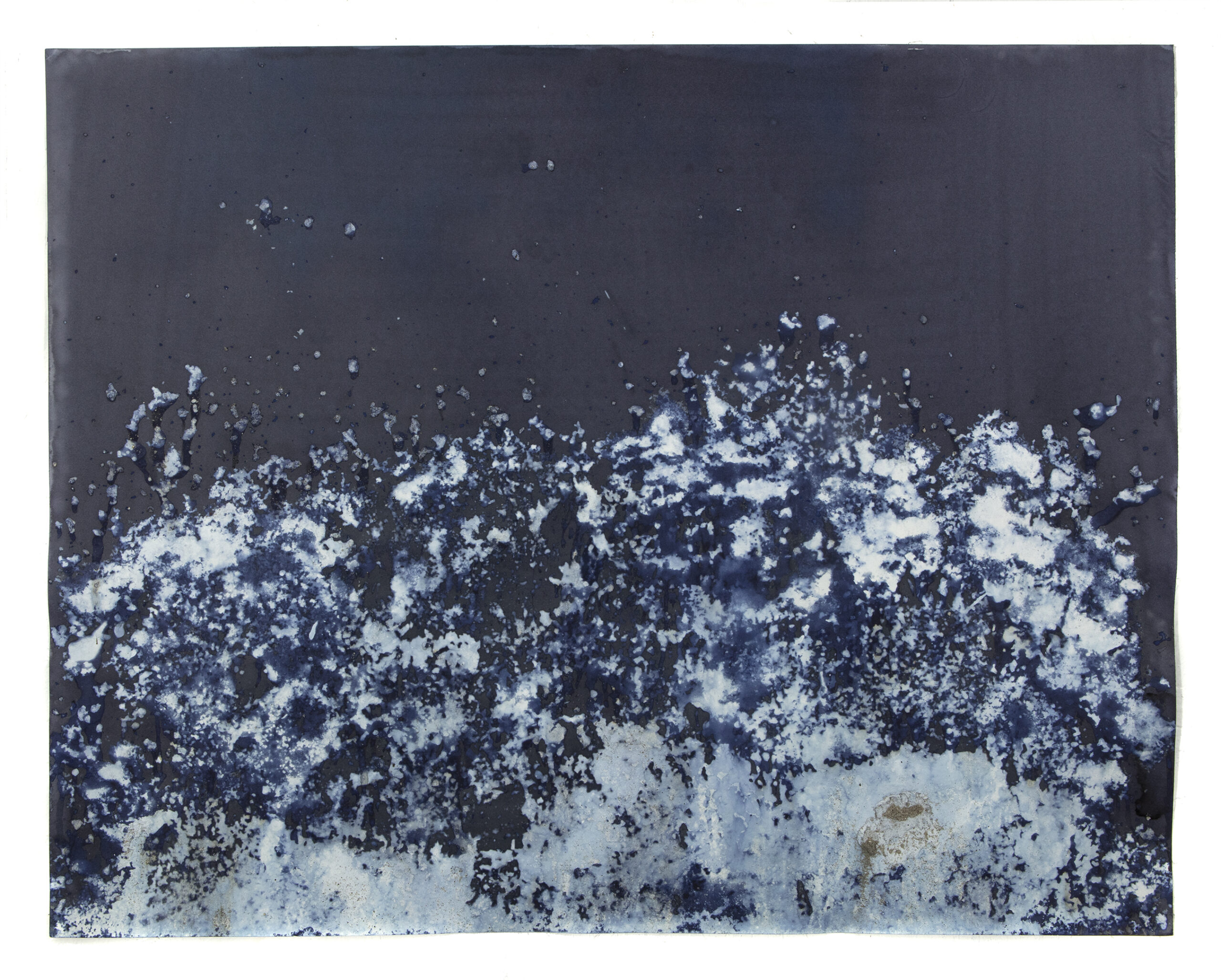

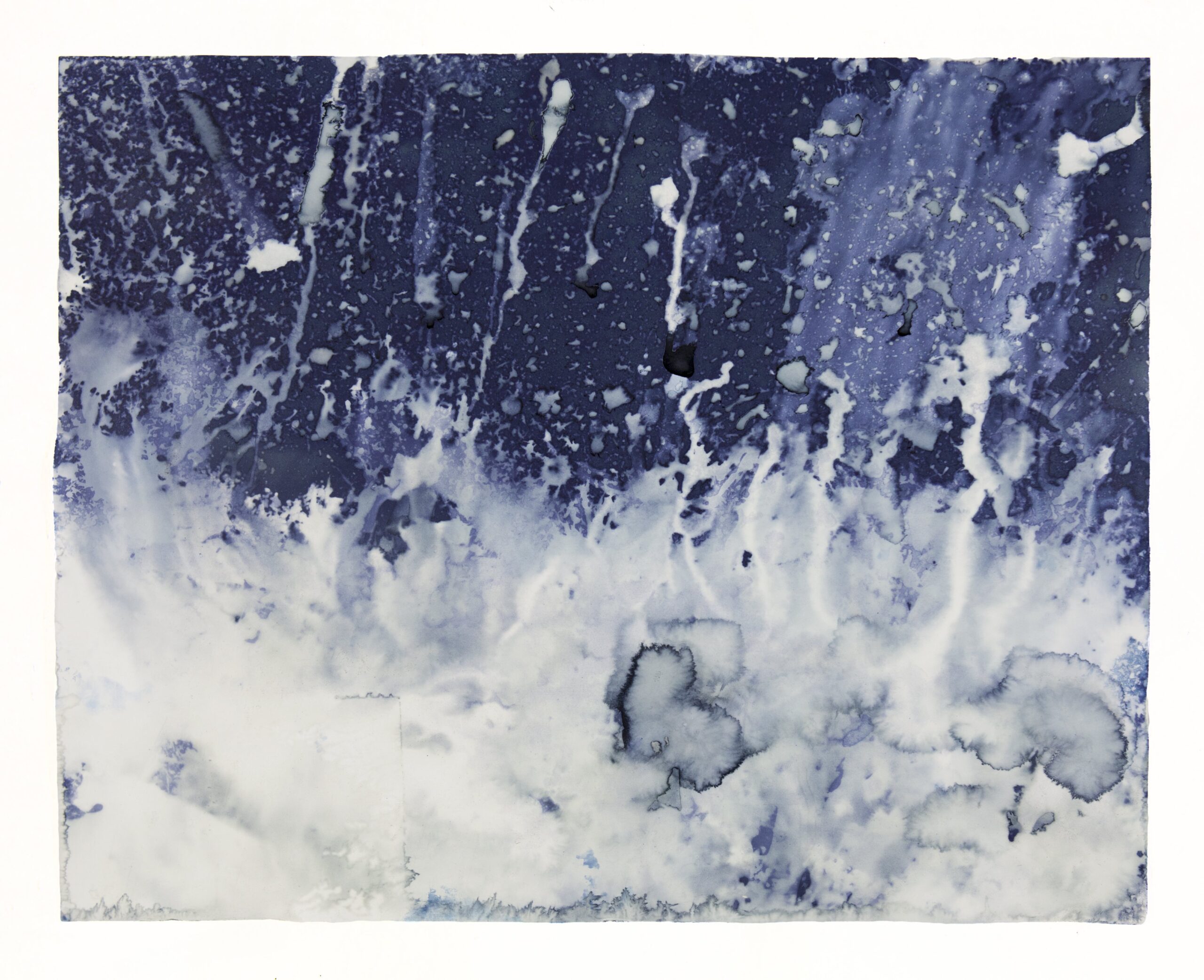

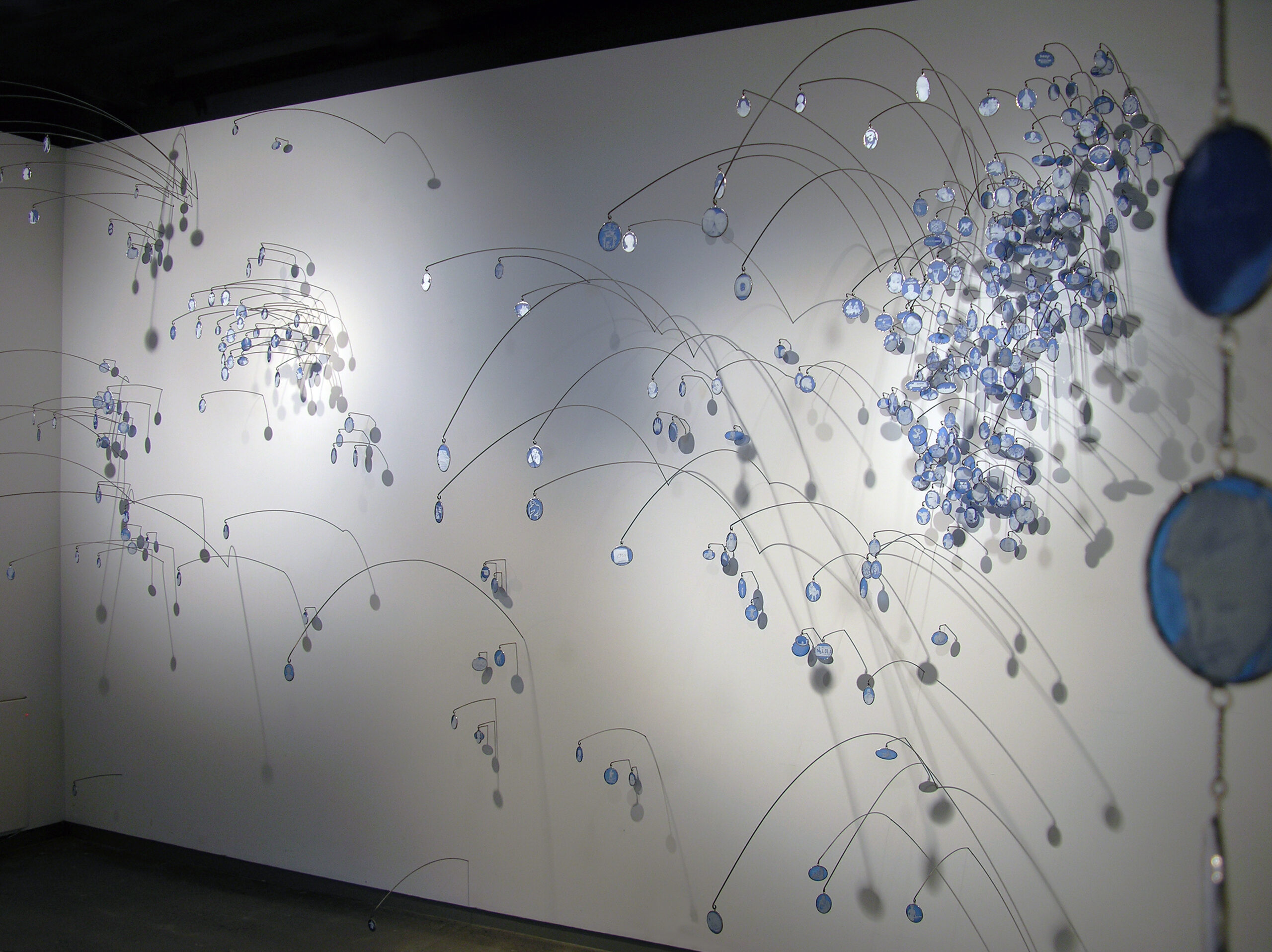

Addressing the 21st century phenomenon of social media is Charlotte Potter’s Pending, a complex work which, when viewed straight on, assumes the form of something like a firework blast. Hundreds of small glass cameo portraits burst out into the viewer’s space, dangling from wires affixed to the gallery wall. It’s a work which visualizes the artist’s pending Facebook friend requests. Potter rendered the profile pictures of each request in blue and white glass, colors reminiscent of a Victorian-era shell-cameo necklace or broach. The length of the wire from which each cameo dangles corresponds to the number of mutual friends Potter shares with each individual. Her rendering of Facebook profile pictures to look like shell-cameos works as subtle commentary on the often-airbrushed and fastidiously curated digital versions of ourselves that we tend to present on social media, which ultimately serve the same ennobling purpose as a Victorian-era cameo.

Charlotte Potter (American, b. 1981). Pending, 2014. Cameo engraved glass and metal, 156 x 360 x 96 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Heller Gallery, New York

Charlotte Potter (American, b. 1981). Pending, 2014. Cameo engraved glass and metal, 156 x 360 x 96 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Heller Gallery, New York

There’s a literal savage beauty in Etsuko Ichikawa’s luminous blue and green spherical orbs which glow in a dark corner of the gallery suite like little marbled earths. The unlikely inspiration for Leaving a Legacy was the Fukushima nuclear disaster caused by the disastrous tsunami which struck Japan’s coast in 2011. After learning that nuclear waste can be contained behind glass in a process called vitrification, Ichikawa created spherical orbs which contain (in every sense of the word) traces of uranium, which causes the orbs to eerily glow when lit by a black light, and they speak to the uneasy proximity with which we coexist today with nuclear energy and nuclear waste.

Etsuko Ichikawa (Japanese/American, b. 1963). Leaving a Legacy, 2017. Hot-sculpted uranium glass, 33 x 72 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Winston Wächter Fine Art, Seattle

In contrast with some of the high-tech and ultra-modern works on view, April Surgent’s Portrait of an Iceberg comes across as an homage to traditional painting; her serene photo-realist work even takes the form of a triptych, which has deep roots in art history. Working from original photographs, Surgent meticulously engraves images of the natural world in glass, and her finished works are evocative of the painted blurry photographs of Gerhard Richter. They’re beautiful, but they also gently speak to the need to restore wounded ecosystems and address climate change. And her slow working method of engraving into glass is a performative act of defiance that pushes against the aggressively rapid pace of the digital age.

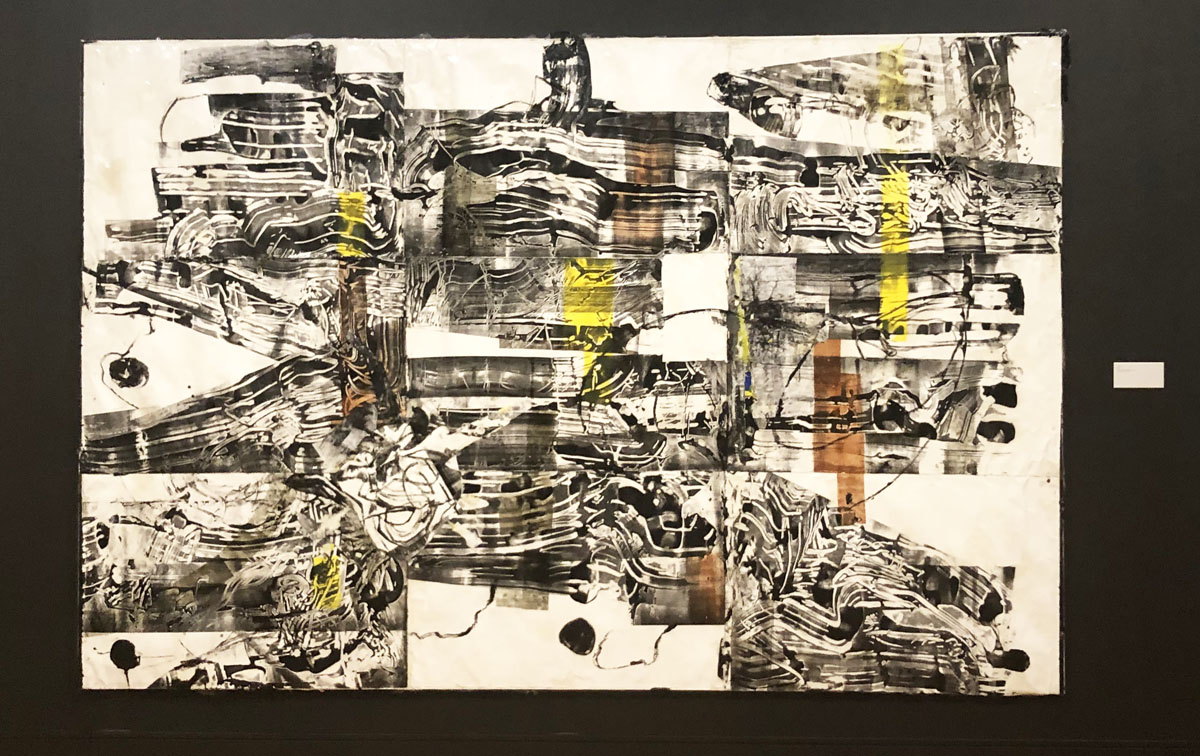

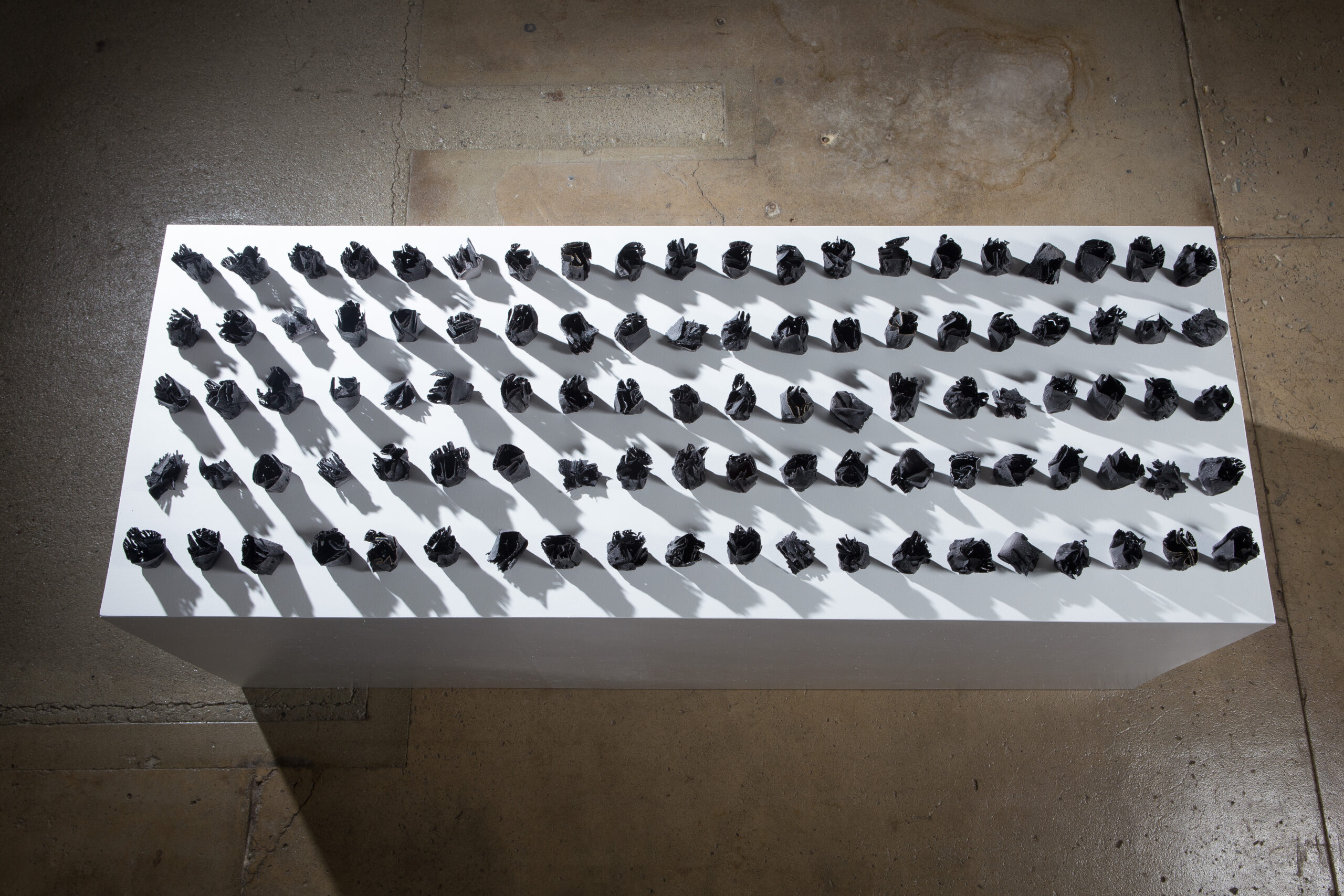

Flaunting the versatility and trompe l’oeil capability of glass, Tali Grinshpan’s Hope is a work that mimics with arresting believability the soft and paper-thin fabric of a Baroque-era ruff-collar. Fragility is a recurrent motif in her work, and Tikun (To Mend) comprises dozens of charred and crumpled brittle-looking vessels in varied states of ruin and (dis)repair. Like a Mark Rothko painting, the work uses the language of abstraction to convey deep feeling, in this case, a meditation on the breaking and mending we inevitably experience in our lives.

Tali Grinshpan (Israeli/American, b. 1972). Hope from the series Of Innocence and Experience, 2016. Pâte de verre, 10 x 10 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Tali Grinshpan (Israeli/American, b. 1972). Tikun (To Mend) from the series Rituals, 2016. Pâte de verre, 100 vessels, 3 x 3 x 3 inches each. Courtesy of the artist.

Complimenting Glass A New State of Matter is an auxiliary one-room micro-exhibition, Looking (at-into-through) Glass, featuring glass as it appears in works from the GRAM’s permanent collection. Paintings and photographs reveal some of the varied and many ways artists use elements like windows, mirrors, and reflections in their work. Bruce McCombs’ painting Ed’s Easy Diner is a watercolor tour de force which renders the shiny and reflective glass facade of a dive restaurant with the same exacting photorealist detail we might expect from a Richard Estes painting. Also on view is Tir (from the Conversion series by Iranian artist Monir Shaharoudy Farmanfarmaian), which was recently purchased by the GRAM; the luminous arabesque patterns on this multifaceted geometric glass sculpture reflect shards of light into the gallery space much in the same way stained-glass windows diffuse light onto a cathedral floor.

Glass, A New State of Matter is a crowd-pleasing exhibition in the best possible sense. It brings together an eclectic and visually exuberant ensemble of international artists whose work addresses issues as varied as identity, environmentalism, PTSD, and even the Avian Flue (Rachel Moore’s rendering of surgical masks tarnished by their wearer’s breath has certainly accrued an uncanny resonance and timeliness over the past several weeks). The eclectic nature of this exhibit perhaps might initially seem to lack a specific point of focus, but that can easily be forgiven; after all, it’s ultimately the varied potential (and indeed the innate beauty) of glass that remains the whole point of the show in the first place.

Glass, A New State of Matter is on view at the GRAM until April 26.