Brienza, Bruner, Galbreath, and Carmen-Vian make drawings that engage

Artists, Sue Carmen-Vian, Joyce Brienzia, Coco Bruner, Lynn Galbreath Image Courtesy of Jeff Cancelosi

Drawing has been around for a while. Think: Lascaux cave in Dordogne, France. And drawing is one of the major forms of expression, concerned with the making of lines, tonal areas, black and white or color, representational or abstract, the work in DRAWN TOGETHER is a strong exhibition, curated by Joyce Brienza. She says, “We are a group of artists and friends who have in common an interest in the idea of drawing as end point rather than merely a preparatory act. We are in love with drawing as a direct, no tech and un-electronic media. We see the pencil in some ways as an instrument of nostalgia, recalling the Renaissance quest for virtuosity. Our work ranges from narrative to abstraction but there is a conceptual bent towards popular culture that questions the separation of fine and applied arts.”

Joyce Brenzia, Mixed media on Paper, 28″ x 22″

Joyce Brienza’s work, Given Name ll, is a colorful mixture of images that seem to have the feminine as a theme with overlapping figure and design elements. The compositional construction provides the audience with her artful dexterity with the human anatomy. She says, “In dreams and memories fragments are all we have to make up the whole. I work with images the way a DJ samples music to create my own brand of visual hip hop. By employing a collage technique, the works are constructed of layered and juxtaposed elements drawn from multiple sources that possess a particular personal and/or social significance. Among these sources are still life objects, toys, atomic structures, old master works, family photographs etc. This re-contextualization of images is a conduit for the generation of new meanings.” Her patterns are critical elements set within a grid that tell a story which resonates with the viewer. The work is both personal, and societal.

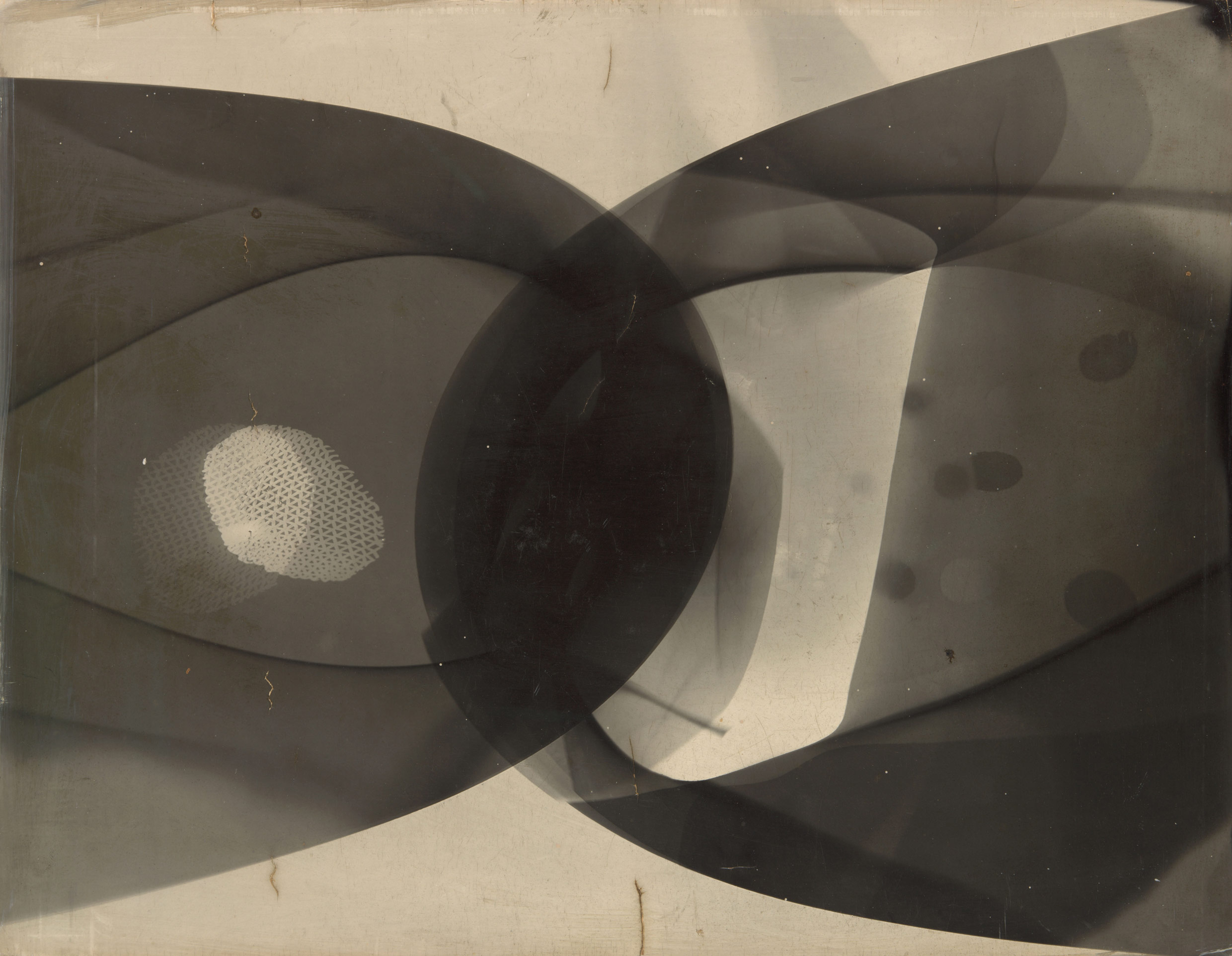

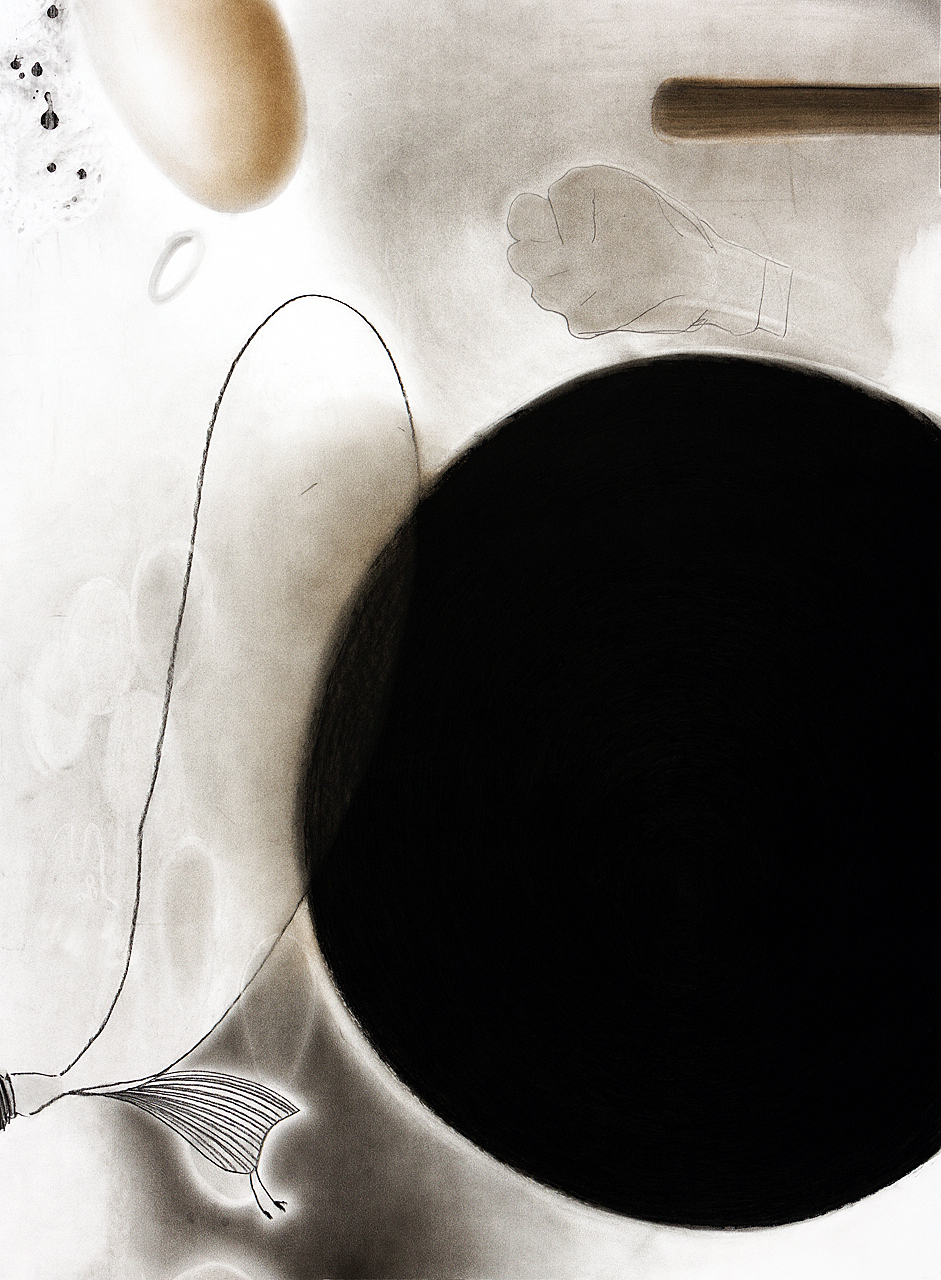

Coco Bruner, Rhymes with Silence, Charcoal and Conte crayon , 30 X 22 – 2015

Coco Bruner’s work, here embellished in Rhymes with Silence, includes a variety of media, in which she manipulates the illusion of space and light. She includes both spontaneous and calculated gestures, while presenting an unconventional composition dominated by this large black circular shape. She says, “Each drawing begins with as spontaneous a gesture as possible. What follows is navigation between control and impulse, the known and unknown. It’s a bit like hitchhiking. You take a risk, not knowing where you’ll arrive, but you’ll probably learn something.” These rather pure abstractions present a sense of mystery that have no definable meaning. An MFA graduate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and recipient of a Kresge Visual Arts Fellowship in 2013, Bruner works in drawing, painting, sculpture and photography.

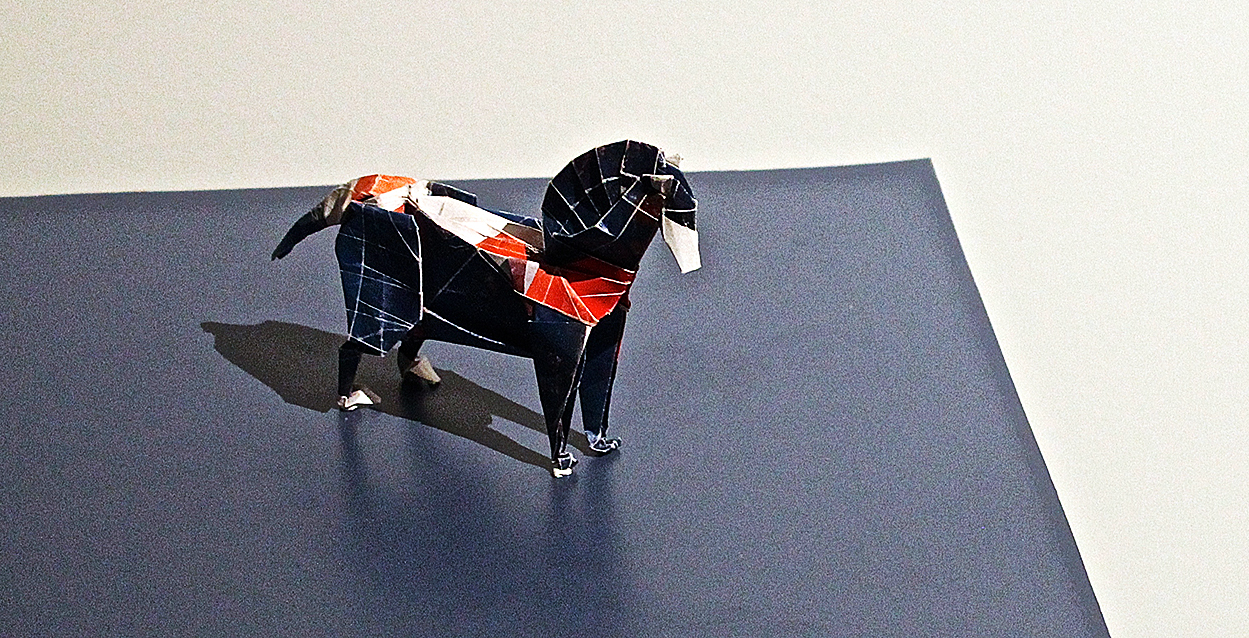

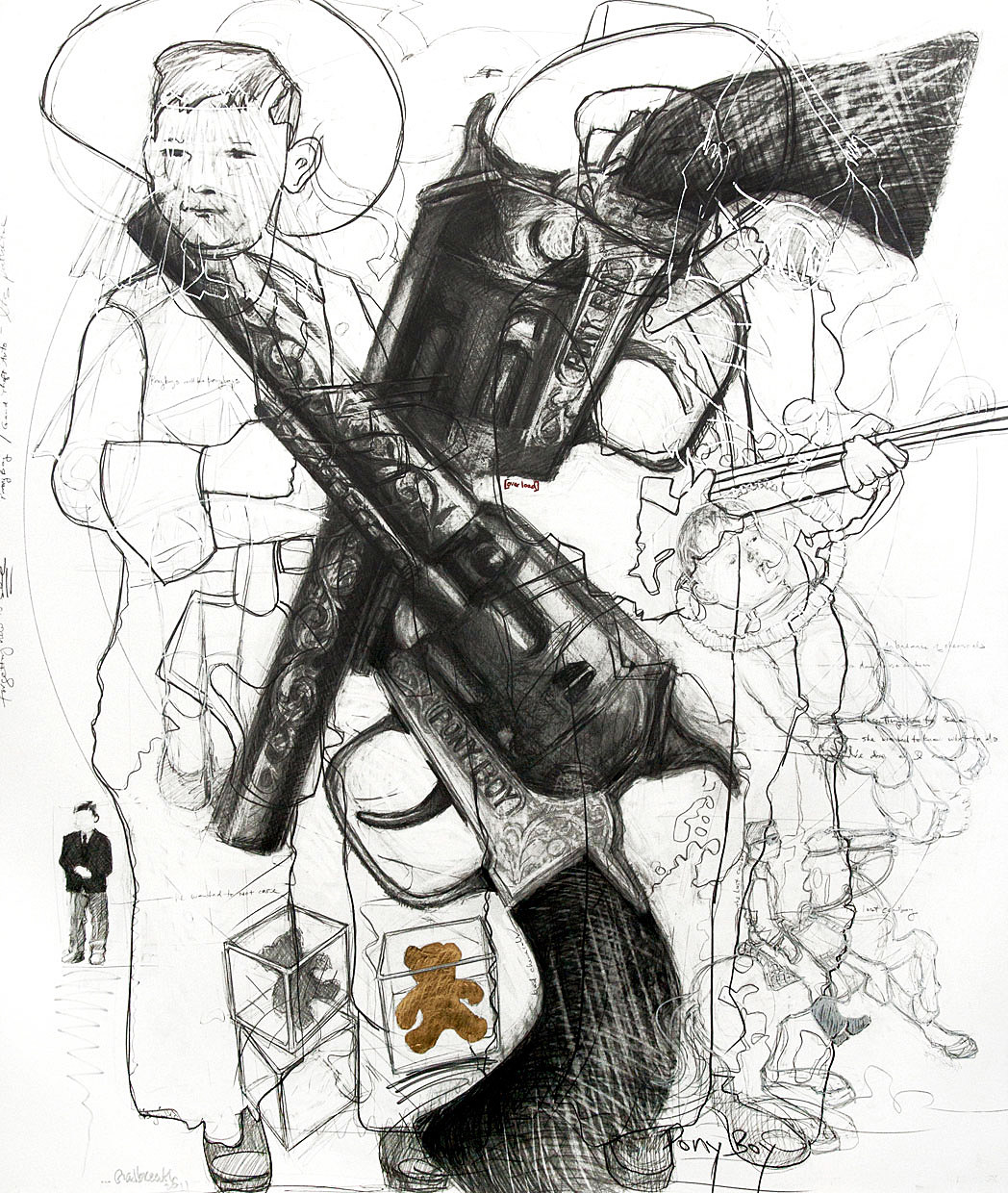

Pony Boy, Graphite and gold leaf on Paper, 60″ x 50″

Here in her drawing Pony Boy, Lynn Galbreath juxtaposes a realistic rendering of two toy pistols against a background of line drawing and creates a young boy’s world filled with imagery and costume. She says in her statement, “I am born to create and cannot function on a daily basis without making something. I create to communicate. To me, art is the conversation we’ve been having since the beginning of time, the one that’s always probing the human condition.” In this drawing, it is the scale that works so well. If it were 8 X 11″, it would feel more like an illustration. Given its size 22 X 40″, the power of scale makes the work stronger, which is not always the case. These toy objects are rendered with such contrast and detail, they take on a life of their own.

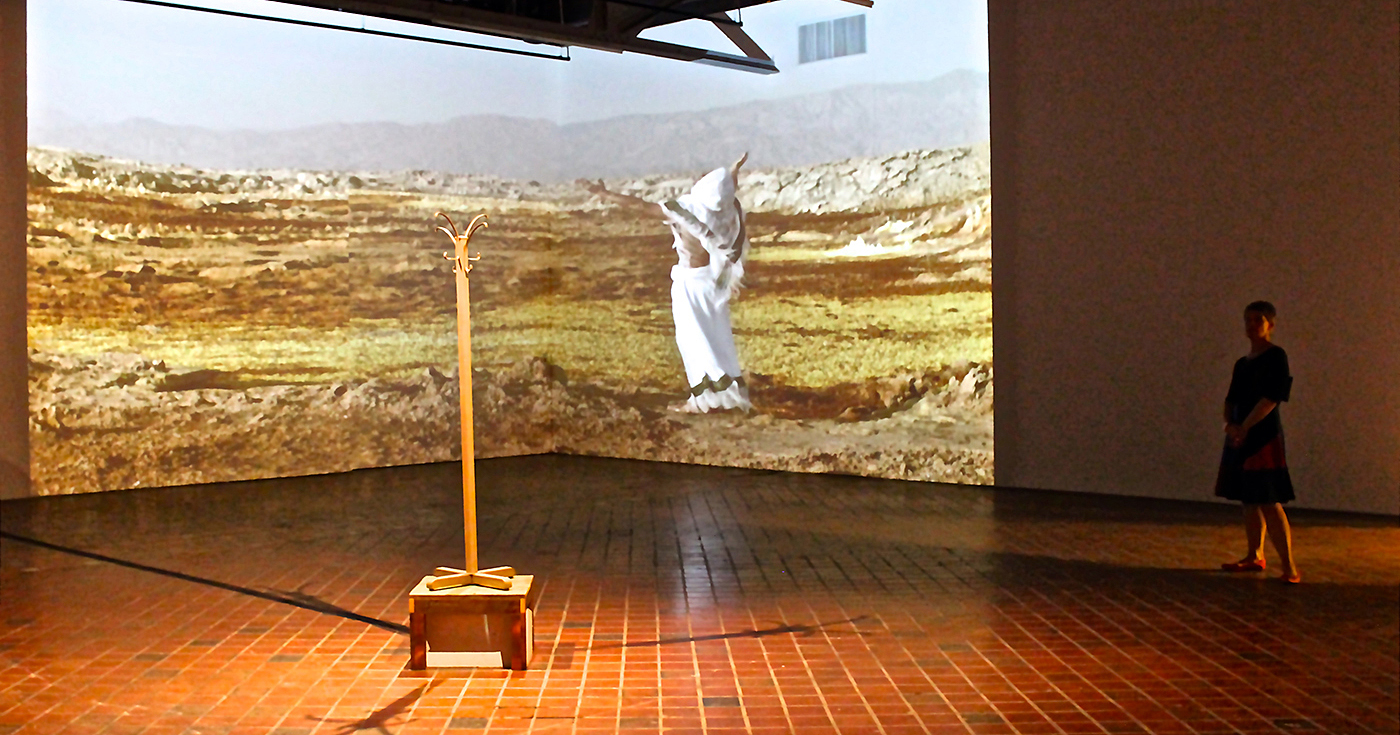

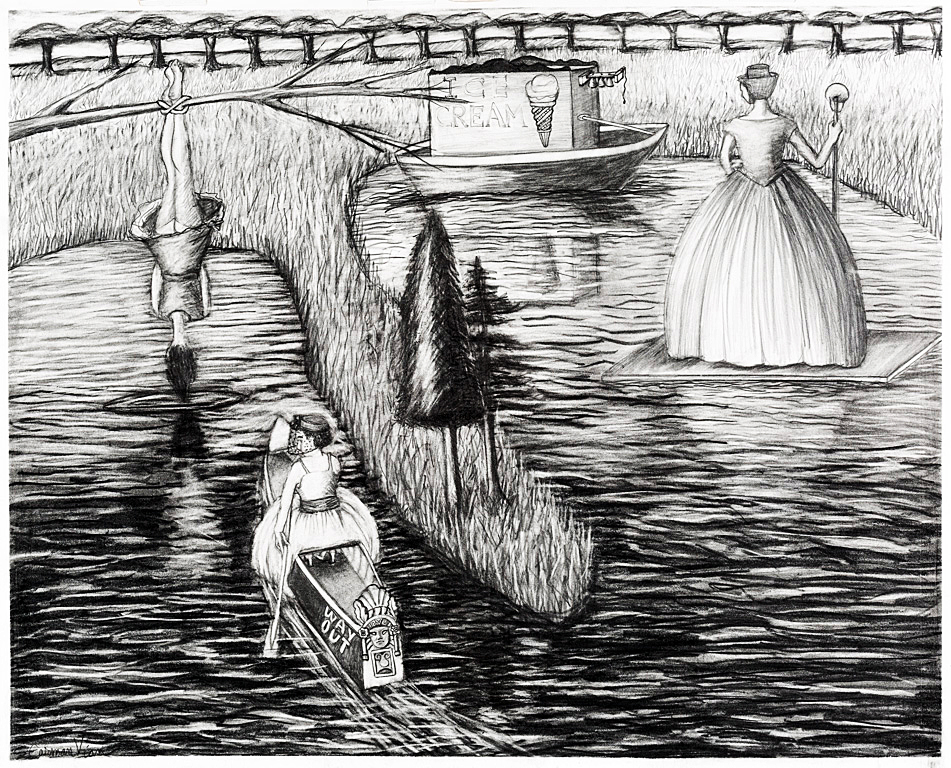

Sue Carmen-Vian, Way Out, 34 x 42 Graphite on Paper, 2016

In her work, Way Out, Sue Carmen-Vian, an MFA graduate from Wayne State University, provides a collection of stylized Van Gogh-like drawings that introduces her audience to a figurative type of surrealism that is personal and at times autobiographic. At a distance, these heavy black and white pencil drawings can have a woodcut feeling with her textural markings. In her statement she says, “The challenge of retirement from teaching is to continue to feel useful. As this part of my life fades my art has become more defined and developed. These drawings contain costumes and props from my on going performance art and teaching days.” On her way out in her new canoe, she seems to be navigating between herself on the right, standing up straight and balanced, versus herself hanging upside down in a quandary. I am sure, since she’s in charge of the canoe, everything will turn out just fine.

On September 9, the first Friday of the new fall 2016 season, there were six openings in Detroit (perhaps more). As I visited each, it wasn’t until I ended up at the Scarab Club that I experienced a loud and joyful community of artists, friends and family, who all had relationships with these four artists. If you’re a painter or a sculptor, it is likely that drawing is at the core of your work. We can look back in history and see the preliminary drawings made by Michelangelo, da Vinci and Rembrandt. Certainly, as demonstrated by these four artists, drawing as an art form is alive and well in history and present in Detroit. The Scarab Club, under the leadership or Treena Flannery Ericson, is the perfect home for DRAWN TOGETHER.

August 31-October 15, 2016 , 7-10 pm Gallery Talk: Saturday, September 24, 2 pm