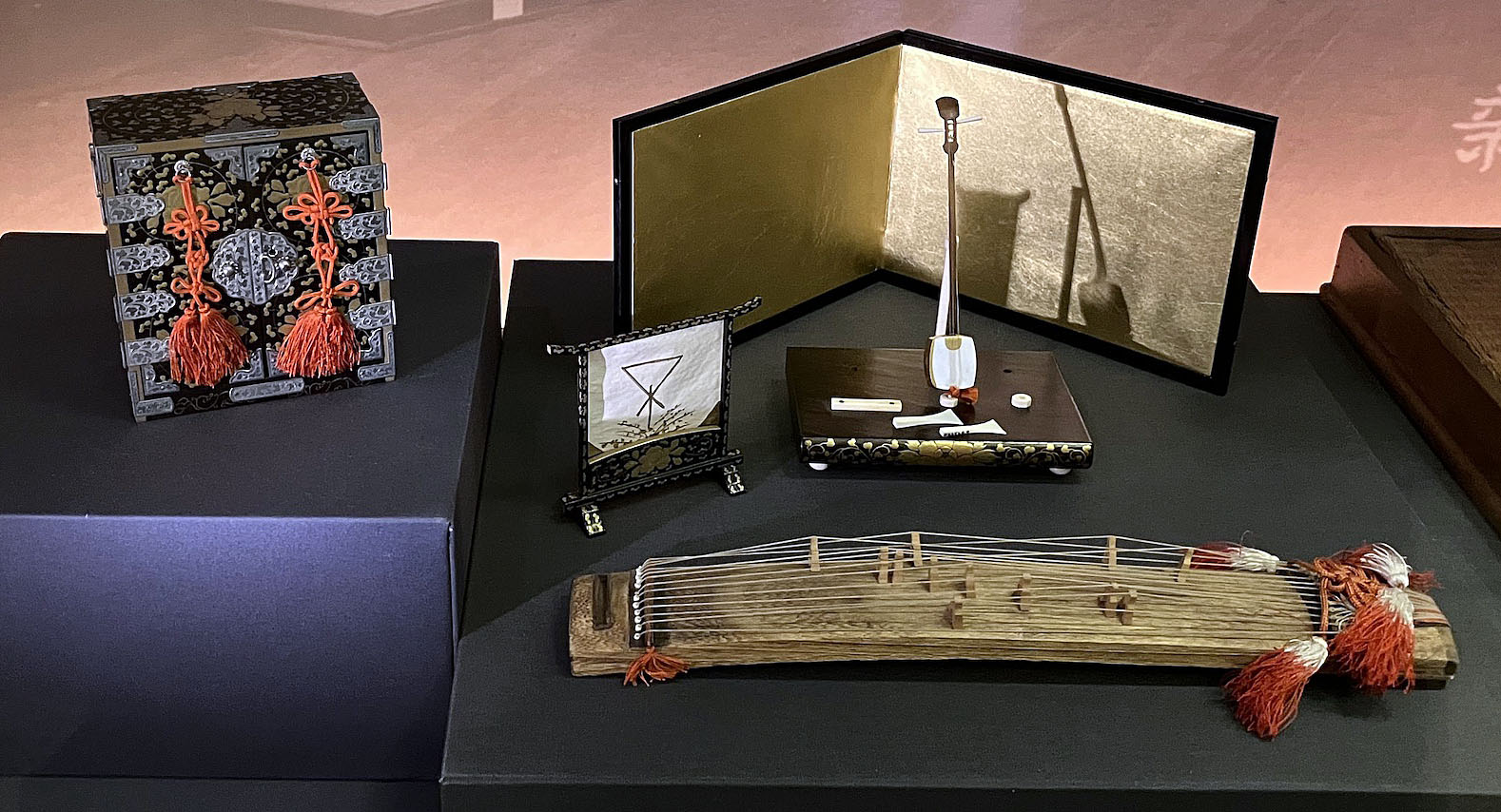

Beyond Topography is a 23-person group show of Michigan Artists at the Janice Charach Gallery

An installation shot of Beyond Topography, a group show up through Feb. 21 at the Janice Charach Gallery in West Bloomfield. (Photos courtesy of Clinton Snider.)

Painter, curator, and teacher Clinton Snider always found early depictions of the American wilderness transporting. Think of the first large room in the American wing on the second floor of the Detroit Institute of Arts, with its canvases crammed with mountains, gorges and other examples of glorious, untamed landscape. Snider acknowledges the current of Manifest Destiny running through many of these paintings, but notes that “at the same time, they’re deeply beautiful and spiritual.”

So when Natalie Balazovich, the director of West Bloomfield’s Janice Charach Gallery asked Snider to curate a show on landscape, he found himself thinking of those classic works, but at the same time, in his words, “reacting against them.” He knew he didn’t want a show of pretty views. His intent was always to bend the landscape paradigm, but still arrive at something with spirituality and force. The result is Beyond Topography, a 23-person group show of Michigan artists up through Feb. 21 that takes a broad view indeed of what constitutes a landscape.

Jim Nawara, Studio View – Powerline Shadows, Oil on panel, 34 x 44 inches.

Studio View – Powerline Shadows by Jim Nawara straddles both the traditional landscape and the unconventional approach Snider is reaching for. The use of color in this lush portrait is exhilarating. It gives the composition three-dimensionality but also amounts to a stirring essay in greens and greenish-blues.

Cutting through this Arcadia, however, are two parallel black lines a little like skid marks – the shadows of overhead power lines that stripe horizontally across tree trunks and bush alike. It’s a human intervention – a desecration, if you will — that on the one hand coarsens this image of perfect beauty, but on the other elevates Studio View above and beyond the merely pretty, landing it someplace immensely satisfying.

Mel Rosas, The Excursion, Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches.

In The Excursion, a peeling wall with a Spanish colonial look dominates the foreground, framing an arch that opens onto a sub-tropical landscape of fields and mountains that beckon like postcards from Eden. On our side of this magic threshold, all is every day and grimy. On the other side lies paradise, and the viewer can hardly resist its gravitational pull. Rosas, who taught for years at Wayne State and says he grew up speaking English but dreaming in Spanish, has repeatedly traveled to Panama, where his father was born. The artist’s work nearly always involves these sorts of gritty, Latin urban vignettes, often pierced by a wormhole into a bucolic past that’s mostly lost or despoiled worldwide. These are visions both spiritual and deeply uncertain. Even within the imaginary logic of the specific painting, there’s no guarantee that the idyll beyond the door frame is accessible or even exists.

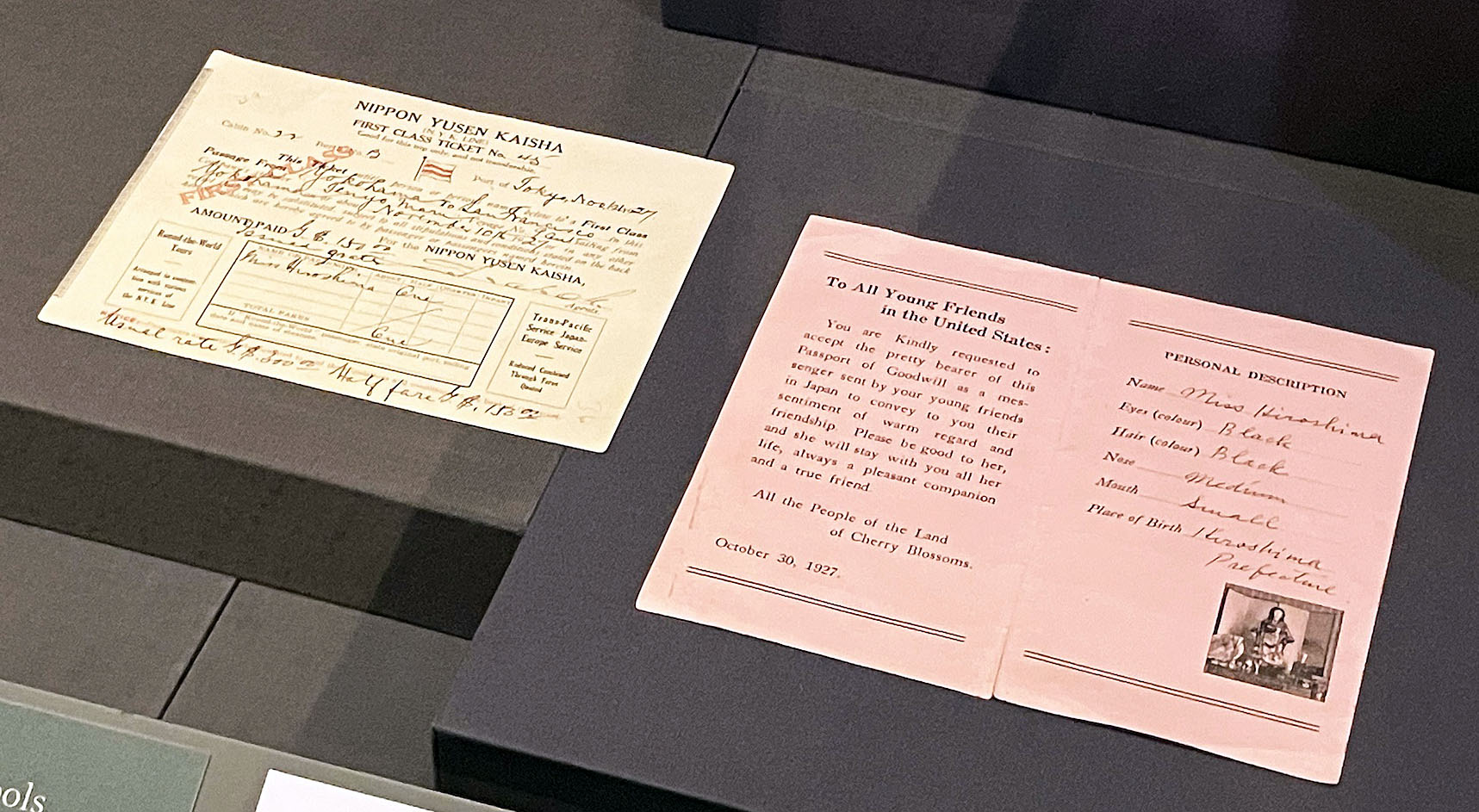

Andrew Krieger, Up North, Edenville, MI, Ceramic, 17 by 16.5 by 15 inches.

Andrew Krieger crushes the world of the diorama. He is the undisputed master of this three-dimensional genre so few artists risk, and one which Krieger inhabits with a pleasing mix of artistic brio and elementary-school goofiness. The artist, who’ s shown in Detroit at Popps Packing and the David Klein Gallery, as well as in Saginaw at the Marshall Fredericks Museum, creates visual narratives that usually involve a 3-D figure in front of a curved background screen. As you move around in front these constructions, changing depth and perspective conjure up an oddball sense of reality. Momentarily, the wooden or ceramic figure at the center of the story springs to life.

In the case of Up North, Edenville, MI, a hale fellow in a down parka and blocky sunglasses waves at the viewer. He’s framed by a shallow ceramic bowl painted in black and white with a surprisingly convincing wintry, wooded scene behind him. The ceramic sculpture of the waving gent in front, a blistering white that pops against its background, is at once funny and dead-on accurate in capturing the 21st-century, up-north Michigan male of the species.

Taurus Burns, To Be Black and White in a Colorblind World, Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches.

The concept of landscape gets pushed to its tight-focus extreme with this black-and-white portrait of a front porch and a man, seemingly grieving, who’s slumped over holding a gun in one hand. Behind him is one of those barred metal doors to prevent break-ins, the sort you see all over iffy neighborhoods. Burns, who’s half Black and half White, has recently produced a series of works examining the nature of this dual identity. With To Be Black and White in a Colorblind World, we’re given a portrait of regret or despair framed by the white metal railings on each side of the porch steps. Burns, who earlier this year had a solo show at Ferndale’s M Contemporary, locates at the exact center of the composition a man hunched over on porch steps, his forehead resting on forearms crossed over his knees. Organizationally, this symmetrically composed portrait resolves itself in a series of superimposed triangles comprised of legs, arms and shoulders — an almost Renaissance conceit in its painterly geometry.

Bakpak Durden, Hanging On, Framed archival print from original negative, 27 x 40 inches.

Who knew a photo of a workman’s winter jacket – the sort Carhartt sells – could be so luminous and affecting? Draped in early morning or late afternoon sunlight on a plywood panel in some indoor construction site, the jacket in Hanging On – a tannish sort of orange – positively glows, while the contrast with the rough plywood and half-erected wall nearby makes the humble overcoat read almost like an object of great beauty.

Durden, who also has the exquisite Renaissance-style painting Mimicry in the show, is something of an artistic polymath. In addition to painting and photography, the artist – with recent solo shows at Cranbrook, the University of Michigan, and Playground Detroit – has turned a remarkable number of walls across Detroit into striking murals. Indeed, it’s hard to spend much time in the city without seeing one.

Denise Fanning, A Soft Place to Land (Rest in Peace), Cotton, beeswax, grass, moss, found remnants of nature, sea grass cordage, 6 x 9 feet.

A Soft Spot to Land (Rest in Peace) by Denise Fanning, who taught for years at the College for Creative Studies but now lives in Mt. Pleasant, creates a peculiar and beautiful “landscape” out of 55 identical off-white square pillows and 55 “nests” or creations she’s delicately placed on each one. While the artist does a lot of studio work and has exhibited in galleries from Detroit to Berlin, lately she’s spent an increasing amount of time out of doors arranging and creating in nature itself – crafting ephemeral installations designed, like much of Scott Hocking’s work, to weather and disintegrate over time.

This pillow field is arranged in a 5 by 11′ grid. If you stand at the narrow end and look up the construction, it does a remarkable job of creating a sense of distance and topography, however orderly and symmetrical. The compositions that have alighted on the pillows are extraordinary miniatures in themselves – tiny essays in natural grace.

Other artists in the show include Mitchell Cope, John Charnota, Joel Dugan, Adrian Hatfield, Scott Hocking, Faina Lerman, Alex Martin, Anthony Maughan, Michael McGillis, Ivan Montoya, Lucille Nawara, Rebecca Reeder, Tylonn Sawyer, Clinton Snider, Millee Tibbs, Graem Whyte and Alison Wong.

The group show Beyond Topography will be up through Feb. 21 at the Janice Charach Gallery.