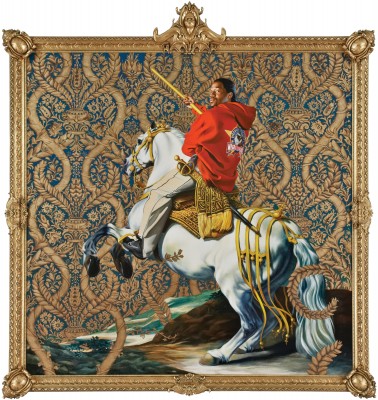

Nancy Mitchnick, The Storm Tree Cycle – Three of four “Storm Trees” on display at Public Pool – All Images Courtesy of Sarah Rose Sharp

Nancy Mitchnick is a Detroit legacy that spans generations. After witnessing and creating work within the Cass Corridor scene, she moved on to find success in New York City, before eventually falling into a series of teaching positions, including working at CalArts in Valencia, California—“the conceptual art school when painting was supposed to be dead”—and a long-term stint at Harvard University. At long last, she has returned to her native homeland of Detroit, and her efforts to make new work and show selections from her existing works have been recently propelled by being named as a 2015 Kresge Visual Arts Fellow.

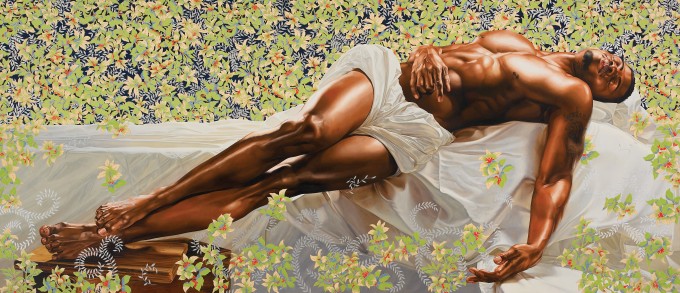

Nancy Mitchnick, Mr. Woodman – Two views of Mr. Woodman: “Mr. Woodman Walking” and “Mr. Woodman Thinking”

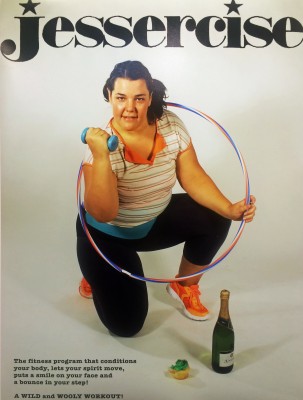

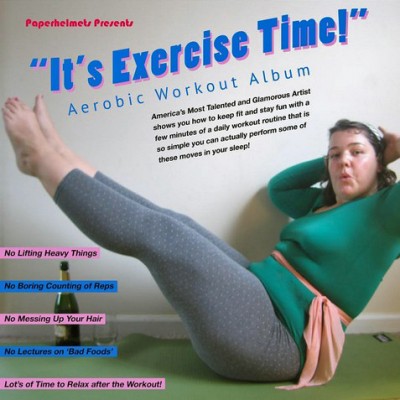

Over the last month, Mitchnick has held court in Hamtramck’s Public Pool community art space, presiding over a solo show titled Storm Trees and Mr. Woodman. The “Woodman” drawings are a series of mixed media pieces on paper starring a figure inspired decades ago by a literal piece of wood that Mitchnick couldn’t bear to sacrifice to her woodstove—but it is the wall of “Storm Trees” that really captured my attention—at once wildly gestural and absolutely formal. Mitchnick took some time out during a work day at her newly enhanced studio space in the Russell Industrial, to talk to me about the creation of these particular works.

Nancy Mitchnick: This is about the tree paintings, yeah?

Sarah Rose Sharp: Yes. When did you do those?

NM: I did them in 2008, the year before I left Harvard. And no one wanted to show them. People wanted to buy them for a little amount of money—two people who collected my work and bought big paintings—and I said, I can’t do it. I just can’t.

SRS: I’m intrigued by them, especially since, as you said, you sort of paint buildings and stuff. I think those building paintings almost look like quilts.

NM: I do love the gird. I’m a grid girl.

SRS: Is that how you lay out your paintings?

NM: Well, not exactly, but often the work is an implied grid. I don’t plan it, I find it. When I was a kid, I never could tell you why I painted anything, and I liked that it was mysterious—the whole process is like a revelation to me, so I never feel like talking about it. It’s like talking about sex. How are you going to explain how it feels? You know, it’s private and between two people—usually. [LAUGHS]

SRS: [LAUGHS]

NM: So I I feel something deeply, and it feels right, and then I make a painting, and I can explain about the formal part. But with the trees that are the gallery [Public Pool]—I was working at a barn, and I passed them every day, and it really is a perfect subject for me, because it’s lyrical but also gridded out, because of the branches. It’s these verticals, with branches that are lyrical behind. It was so beautiful to paint them. I guess I’m a sensualist, and I want an experience that’s joyful when I’m painting.

I turned the work into different kinds of adventures. Like, I’d be teaching at Harvard, in claustrophobic Cambridge, and then I’d go to this big old messy farm that’s been in business for centuries. So I got to have this fun in this beautiful place, and do my work—and it cost, I don’t know, thousands of dollars to ship a whole studio, for three or four months. It was an expensive proposition, but I’ve done it.

And maybe it’s because I’m ADHD, plus slightly dyslexic, but smart somehow—I can sort of jump from subject to subject a little bit, in the paintings, as well as in conversation.

SRS: In a single painting, or from painting to painting?

NM: No, from painting to painting. And then things happen that you really don’t plan. I’ve read history and science, you know, it happens to everybody. Everybody’s got stories about how they went out to do one thing and another thing happened. I’ve always felt sort of nuts, but it seems like it’s a very common occurrence. So I go up to Peru, New York, just to work in the landscape, and also to work in this big barn—but the landscape was way too green, and I didn’t really find anything—I was looking in the wrong places. And I passed those trees every day on my way to the barn, and I never thought to paint them. And I started the house paintings that summer, which really, I’m still trying to figure out what to do about Detroit, how to paint about Detroit. And those houses were kind of an aside.

Nancy Mitchnick, studio – Some of Micthnick’s new work in progress, just after moving into her newly appointed studio space

So there I was, trying to figure something out, and my friend was coming through, and he said, “God, isn’t that a natural subject for you to paint?” And I just looked at the spot, and I realized it was just perfect. I had big stretchers set up for another project entirely, and I got very, very excited because I’d had such a strong feeling about them. I just knew that they were immediate, that they were abstract, that I loved the underpainting, and that I couldn’t fuss with this. I just knew not to make them pictoral, and anyway, how could you? I was far away from it, and they were so gestural.

So I just set them up, and it really was terrific fun. I had an 8-foot palette; I must have put down three pounds of white paint. The palette was very limited—terra verte, ochre, raw umber, olive green deep, white, I probably used some gray, with a little bit of cadmium green now and then. It was a simple, simple set of colors, and it must have taken an hour and a half to mix a palette. My arm would get tired, because I was using lead white, which is heavier. And then I’d take a little break, then I’d set it up—and then I would just make those paintings in a day. I never had so much fun, actually.

I felt, you know, when I was a kid, I just wanted to be an abstract painter. I always wanted to be a different kind of painter. Who knows? Maybe it will work out in the end—because I’ve tried to change, and you are who you are. And you really mess up if you try to work against what comes naturally.

SRS: Well, right. It’s like pretending to be someone you aren’t to date someone. All you do is commit yourself to never be appreciated for who you are.

NM: Exactly, and then you’re miserable. So that was such a natural subject for me, and so joyful, because it was abstract, but it really was observing something from life. I painted the whole under-painting, and then for the big tall trees, I just loaded the brush, and just started at the bottom, and just pulled it all the way up, 7½ feet, and that was it. And I didn’t know if they were good or bad, I just knew I loved making them, and they felt right. I liked them a lot.

“Storm Trees and Mr. Woodman” showed at Public Pool, September 12th-October 17th.