Dark Haring Rises: 30 Years After its Installation, Keith Haring’s “The Detroit Notes” reappears at Cranbrook Art Museum

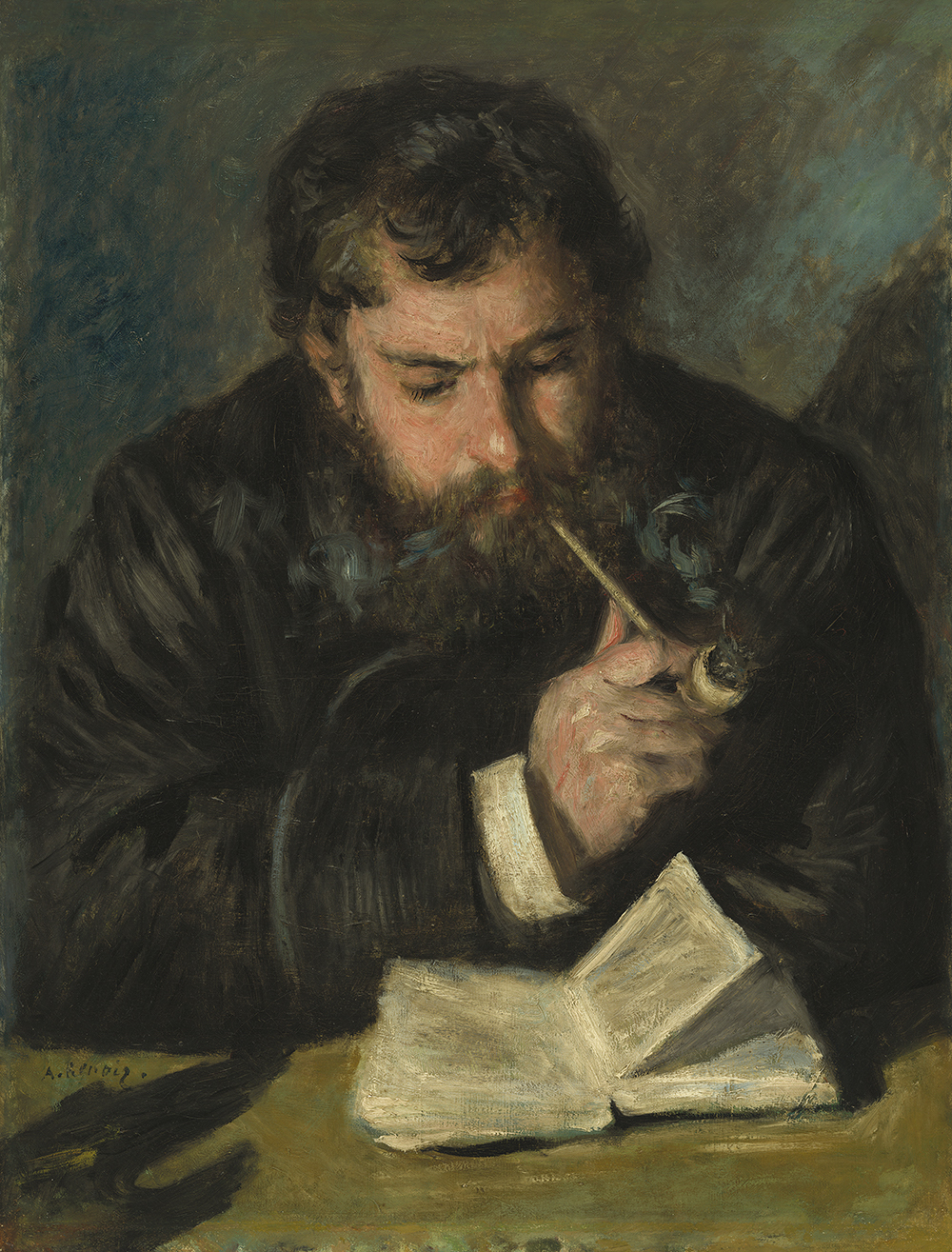

Keith Haring at Cranbrook Art Museum, 1987 Photograph by Tseng Kwong Chi, 1987 © Muna Tseng Dance Projects, New York Art work: © Keith Haring Foundation, New York.

Keith Haring is internationally known for his ebullient and evocative figure drawings, rising to art world fame in the mid-1980s on a wave of graffiti-influenced NYC street culture. Like many of his contemporaries, Haring was part of an early wave bringing art to market as a prestige commodity, and like many of his fellows, he died at a lamentably young age due to complications connected with AIDS—in Haring’s case, at the age of 31, in 1990.

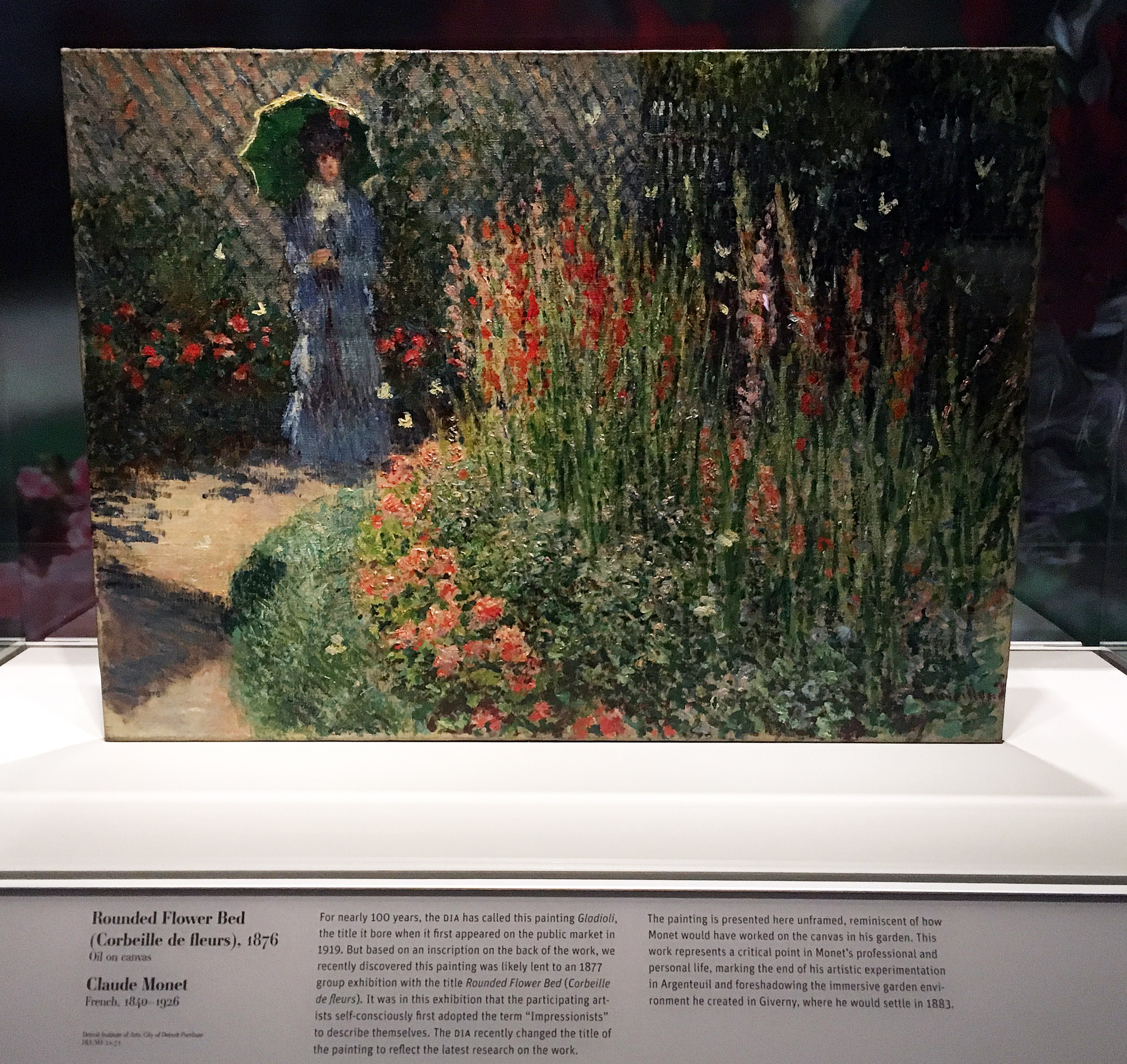

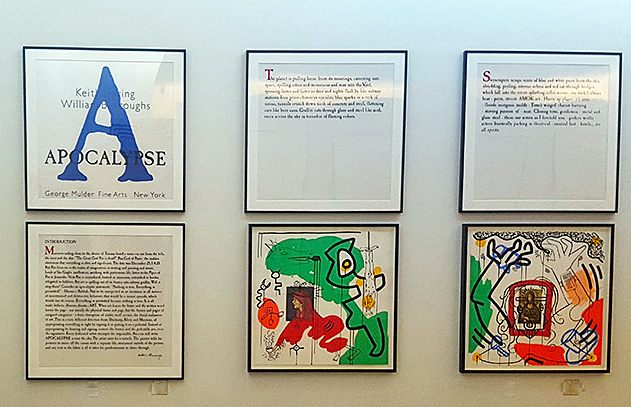

Keith Haring, Apocalypse (1988), by Keith Haring and William S. Burroughs (installation view)

As part of its Fall program, the Cranbrook Art Museum presents a small suite of works by Haring that bookend his career, Keith Haring: The End of the Line. The centerpiece of the exhibition is a reconstruction of a temporary mural, “The Detroit Notes,” installed at Cranbrook in 1987, bracketed on either side by a gallery of very early and very late work by the artist.

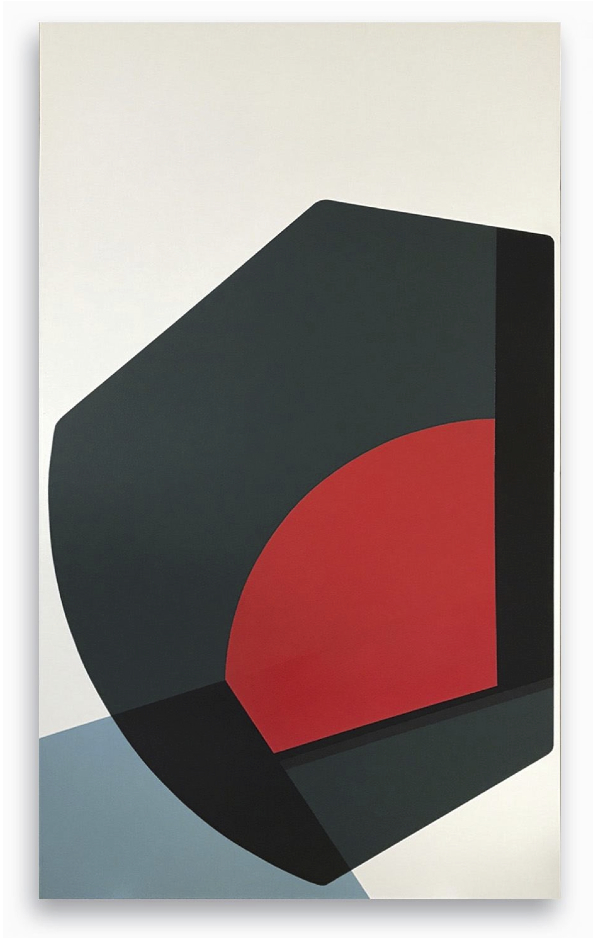

Cranbrook Art Museum Director Andrew Blauvelt poses in the reconstruction of “The Detroit Notes” 1987 mural by Keith Haring

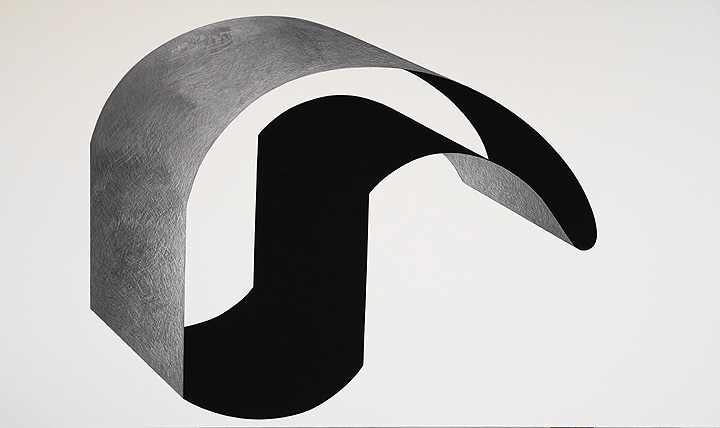

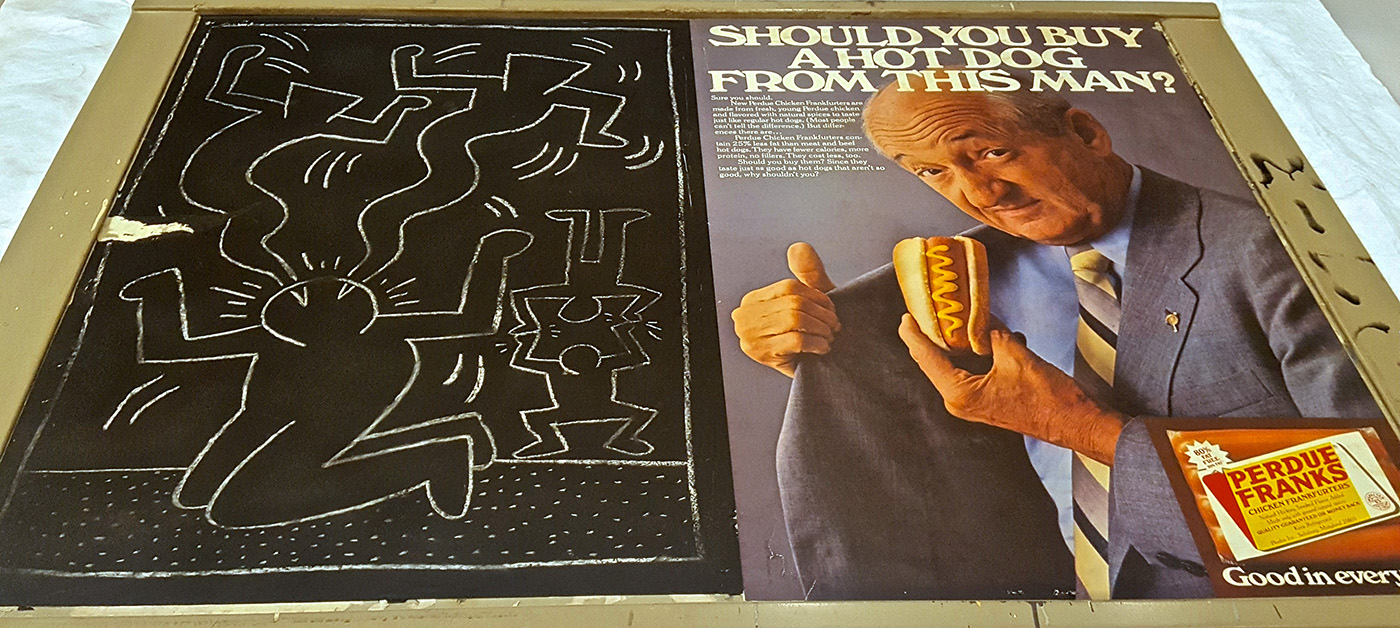

“There was the sort of public persona of Haring, and the kind of drawing that he would put out in public, versus the kind of things that he would do post his AIDS diagnosis,” said Andrew Blauvelt, Director of the Cranbrook Art Museum, by way of introducing a wall of documental photographs taken by Haring’s friend, artist Tseng Kwong Chi, who also died of AIDS in the 1990s. These photographs capture Haring at work adorning New York City subway station advertisements with his signature iconography, and are mounted opposite a rare example of one of the actual billboards. In the piece, Haring’s work is juxtaposed with and ad for Perdue Franks asking, “Should you buy a hot dog from this man?” and demonstrates the artist already in command of the cartoonish and highly abstracted figures that would populate and morph throughout the course of his career.

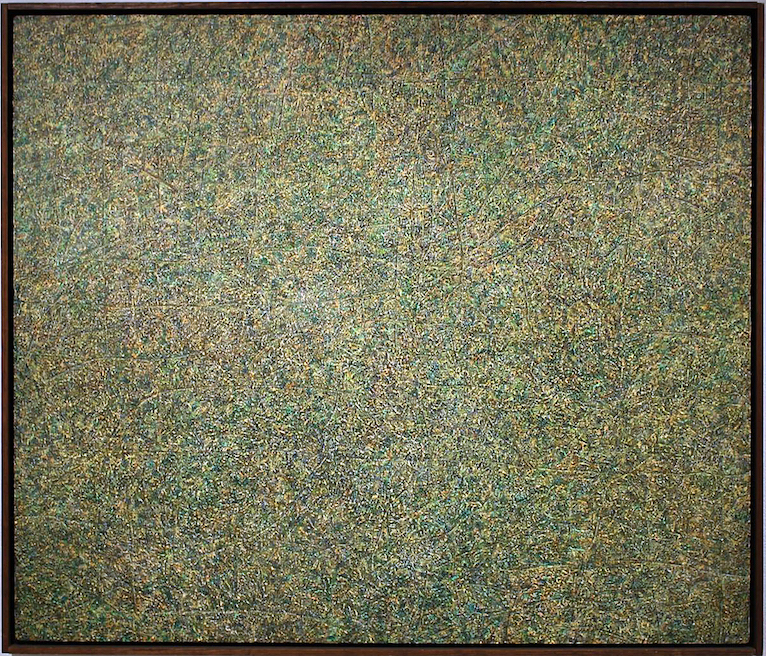

Also on display is Haring’s thesis project from SVA, a video titled “Painting Myself into a Corner,” wherein the young artist does literally that. “He did a lot of work that was floor-based, [Jackson] Pollack-esque,” said Blauvelt, “and then picked up the kind of iconography that he was known for. That video showed him working in a performative way, and we wanted to pull that out, because he always thought of his practice as performative.“

This aspect of Haring’s work stands in conversation with another of the shows in the Fall program, Maya Stovall’s Liquor Store Theatre Performance Films, which combine cultural anthropology, dance, and performative public spectacle into improvisational encounters between Stovall (and other dancers) and random Detroiters on their way in and out of liquor stores.

Blauvelt and Senior Curator Laura Mott point out details in the Keith Haring mural

“A lot of these historical art figures, like [Jean-Michel] Basquiat and Haring, didn’t quite fit into easy categories, and the same is true of Maya Stovall,” said Blauvelt. In her first solo museum show, Stovall presents a set of existing works, including those that were a part of this year’s Whitney Biennial, as well as a new piece in the series commissioned by Cranbrook. Just like Stovall’s newest video work, Haring’s mural was a commission for the museum, and the exhibition happens to coincide with the 30-year anniversary of the mural’s presentation, which was also accompanied by a lecture.

“I started drawing in the subway in New York City in 1980,” said Haring, during the lecture, which took place on September 25, 1987. “…The situation sort of presented itself almost by accident. …For the first time, it seemed like I had made something that made sense to be in public because it had a kind of communicative power.”

Indeed, while Haring’s style is instantly recognizable, it is perhaps the somewhat blank nature of his figures that make them so accessible and universal. But the Cranbrook murals reveal a new phase in Haring’s works, what Blauvelt characterizes as “dark Haring,” and speculates foreshadows the public revelation of his AIDS diagnosis.

“He’s officially diagnosed in ’88 or ’89 with AIDS,” said Blauvelt. “But I think he understood that he was going to succumb to it, because most of his friend by that time were diagnosed.” Though Haring’s themes were often political and social, the work at the end of his life and career took a turn toward the deeply personal, and the scale reconstruction of “The Detroit Notes”—including a video of Haring executing the project—captures some of this new style.

The original subway advertisement billboard ‘vandalized’ by Haring during his run of subway art in the early 1980s.

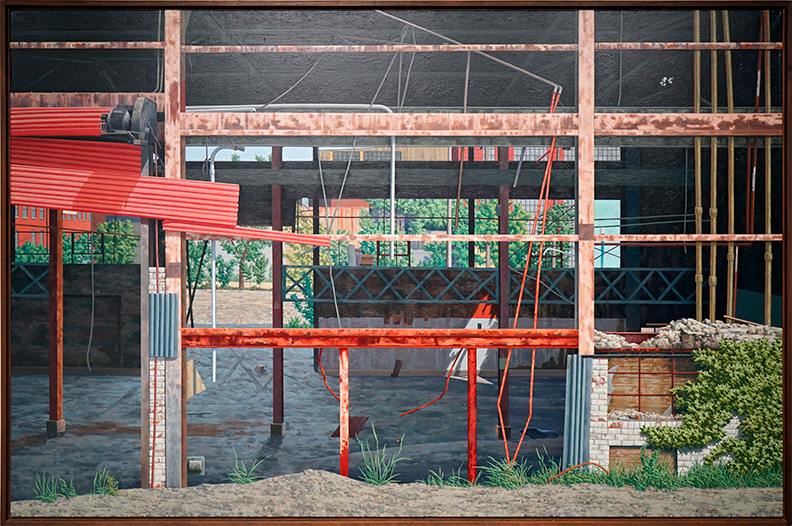

Haring worked for two solid days on the mural—which was always understood to be a temporary installation—first laying down washes of orange, yellow, red and green, then circling back to doodle in black paint over the backgrounds. Though definitely expressing a Surrealist bent—dismembered robot-aliens and frightening, mythical demon-beasts—the work is nonetheless some of Haring’s most figurative, giving faces, albeit grotesque and monstrous, in place of the usually blank bobble-heads for which is he is best known. Bodies are rendered with genitalia, and in various states of dismemberment, televisions blare telescoping stacks of figures, a rosary hangs from a disjointed robot spine. The imagery is immersive and disturbing, and the reconstructed hallway closes in on the viewer as did, perhaps, Haring’s unshakable sense that the demons that were claiming so many of his art world brethren were closing in on him, as well.

Those looking for respite are unlikely to find it at the end of the mural hall, where the final gallery presents two late-life collaborations between Haring and notorious beat poet William S. Burroughs—Apocalypse (1988) and The Valley (1989). One is a series of illustrations made by Haring in response to an existing text by Burroughs; the second presents large-scale prints combining Haring’s images with a new work by Burroughs, developed in conversation with Haring after hearing of the artist’s interest in his writing. It is a fine meeting of two souls on the brink of darkness—Burroughs, who had written himself up from darkness (that included “accidentally” shooting his second wife, Joan Vollmer) to flourish as a gentleman junkie, and Keith Haring, who had gone from rising star into meteoric fall, finding himself at last in a corner he couldn’t paint his way out of.

Keith Haring: The End of the Line runs through March 11, 2018 in the Wainger Gallery of the Cranbrook Art Museum.