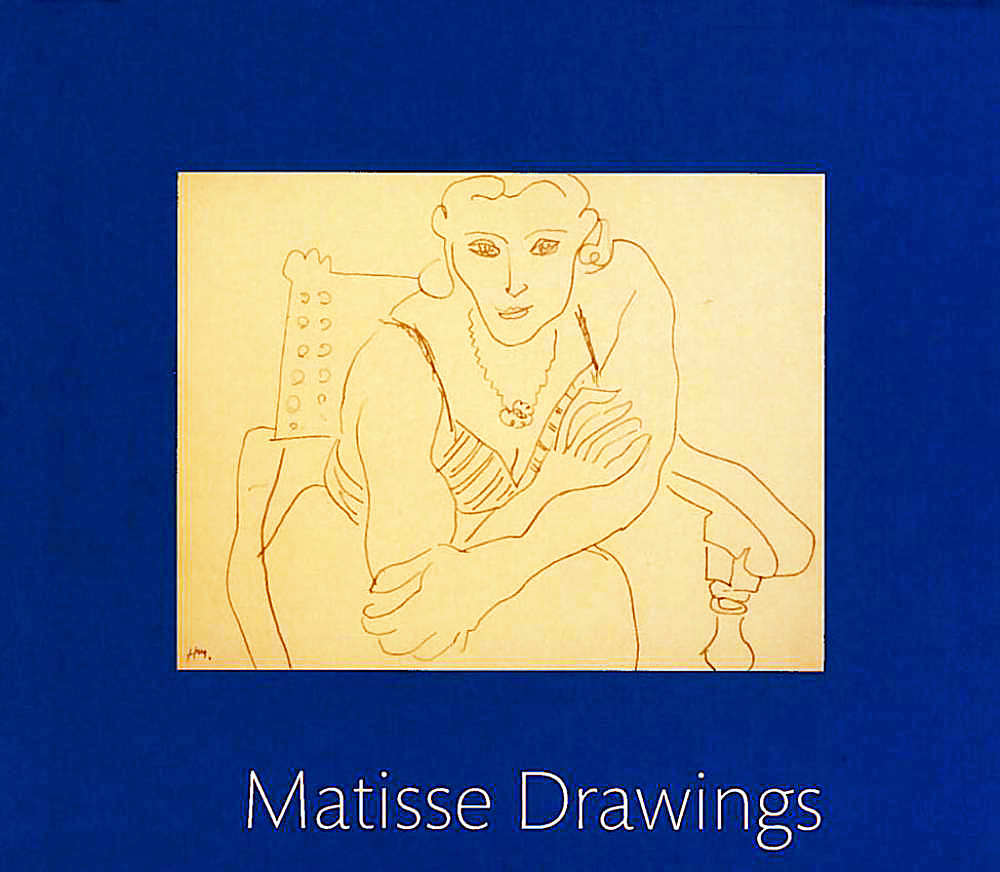

Matisse Drawings: Curated by Ellsworth Kelly from The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation Collection

UofM Museum of Art, Exterior, 2017 Images Courtesy of Levi Stroud

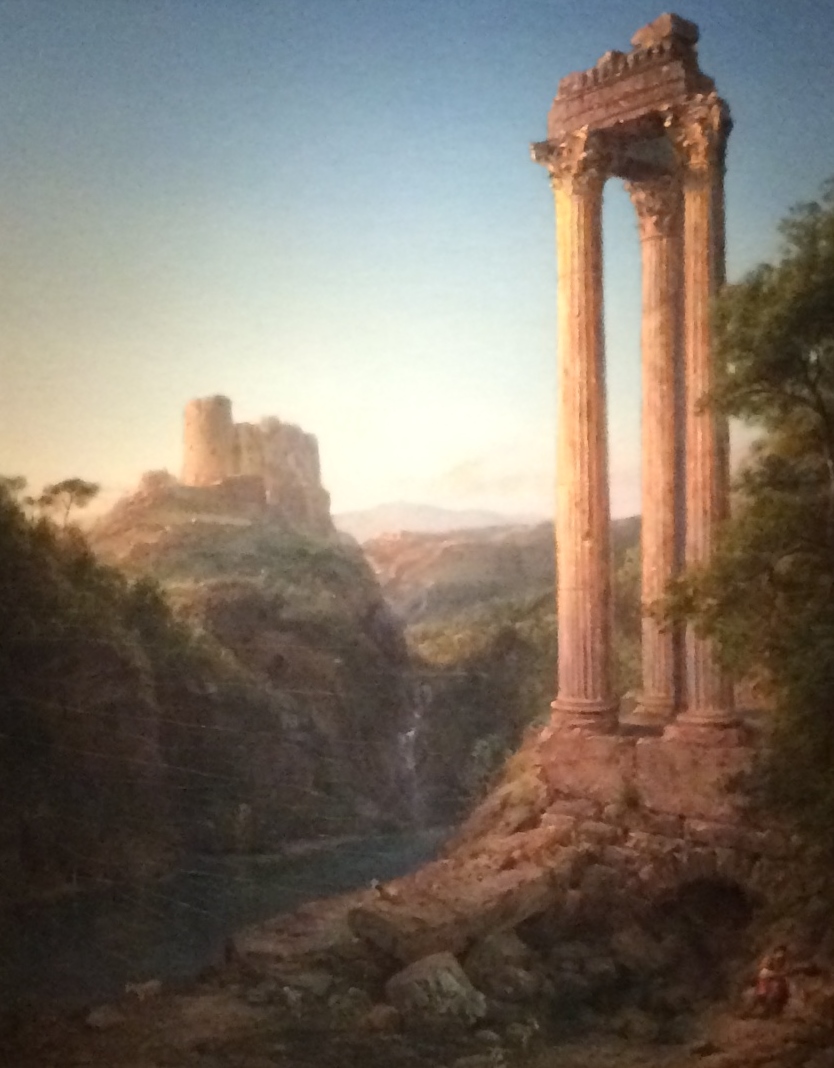

Matisse Drawings, a traveling exhibition currently gracing the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s cathedral-like A. Alfred Taubman Gallery, presents a spiritual meeting of two Twentieth Century titans- Henri Matisse, one of Modern Europe’s most beloved painters, and Ellsworth Kelly, king of the hard-edged color field painting that branched from Abstract Expressionism in mid-century America. The exhibition, lovingly curated and meticulously arranged by Kelly, encompasses an unbroken row of neutrally framed drawings that snakes around the walls of the Taubman Gallery. Nestled in a smaller gallery next to Taubman is a collection of Kelly’s own lithographs, made during a stay in France, inspired both by Matisse and the landscape that inspired the Fauvist master.

Henri Matisse, Catalog of Drawings from exhibition 2017

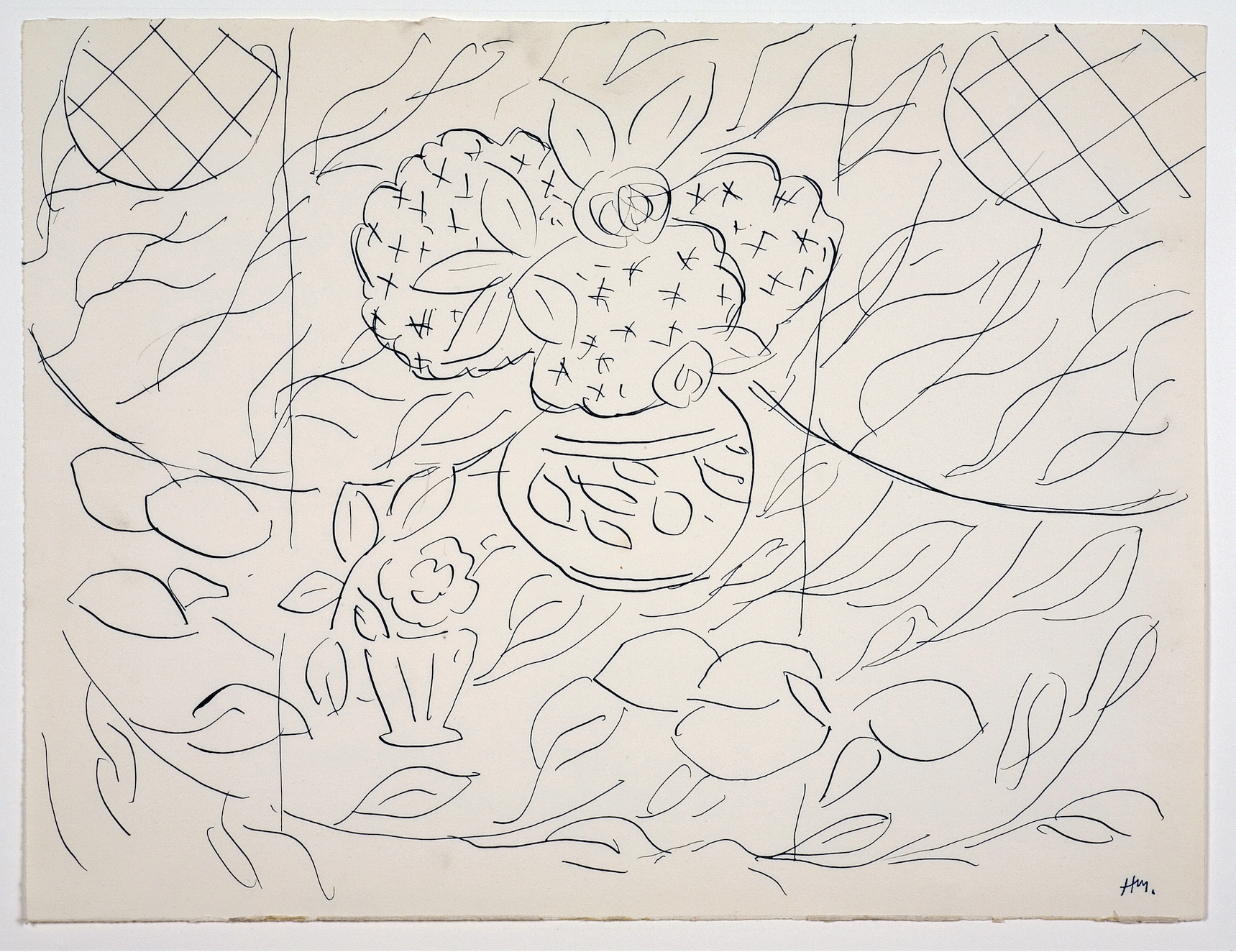

Coming into the presence of a Matisse painting is invariably moving, profound, and difficult to describe. He was a master of emotive, ecstatic visual expression. As formal, flattened, and abstracted as his work can be, there is always, uncannily, a sense of natural light, and plenty of breathing space. Though formidable, Matisse’s works never feel closed off- they invite the viewer in to dance with them. Ellsworth Kelly himself points to this phenomenon in an interview enclosed in UMMA’s gorgeous exhibition pamphlet- “Matisse evoked space. For instance, when he would do leaves or fruit or still lifes, he would leave openings. Like this would be a leaf (gestures in a vaguely C shape in the air). But my drawings are about shapes: the forms are closed.”

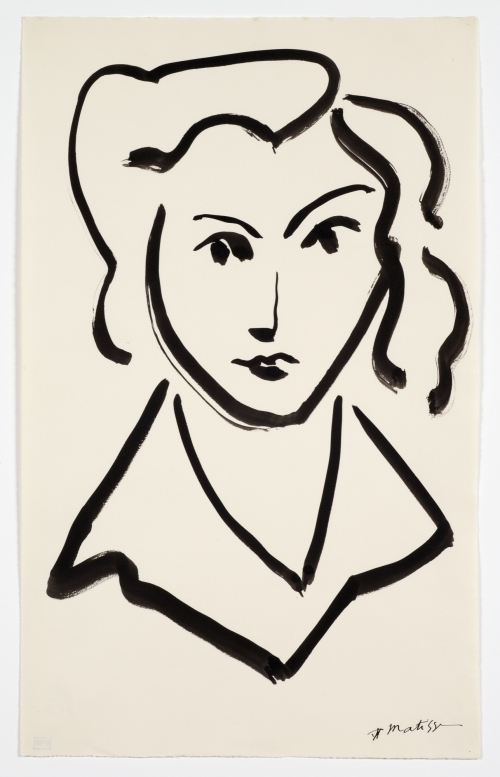

Henri Matisse, Drawing, Head of Woman, 1945

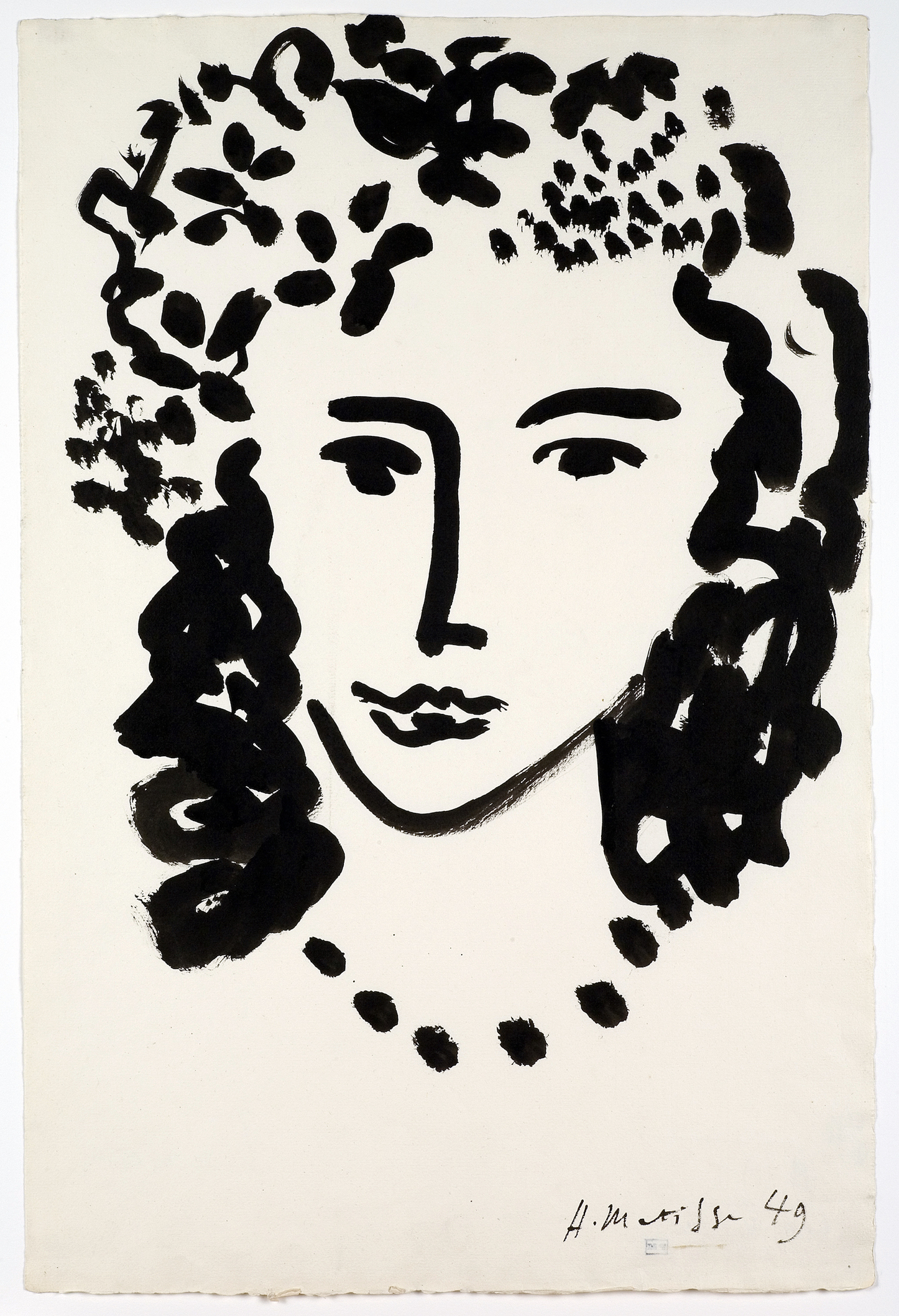

Matisse was a magician of open form. The feeling of completeness, along with the lack of fussy detail, gets more astonishing with each passing drawing. The graceful bend of a plant stem, the nuanced tilt of a woman’s head, the fleeting glance of the artist himself peering around his drawing board in a self-portrait, are conveyed with a mind-bending economy of marks. Matisse’s marks contain multitudes. The shift from point to edge of drawing tool in one sweeping contour imply light, shadow, movement and space with such apparent effortlessness that one is first skeptical, then seduced, then transcended in following it along the curve of a cheek or the plume on a hat. This strikes the deepest in Matisse’s studies of shoulders and arms- as simply as they’re drawn, they distill the formal heart of the Odalisque in bent, foreshortened elbows as hands reach up to tousle hair, the sensuous weight of a torso rests on crossed forearms. There’s a purity to these drawings that somehow transcends Orientalism in way’s Matisse’s predecessors and contemporaries did not- they’re about life, movement and muscle, the glorious freedom of the sensuous body.

Henri Matisse, Drawing, Sketch for Lemons & Mimosas, 1944

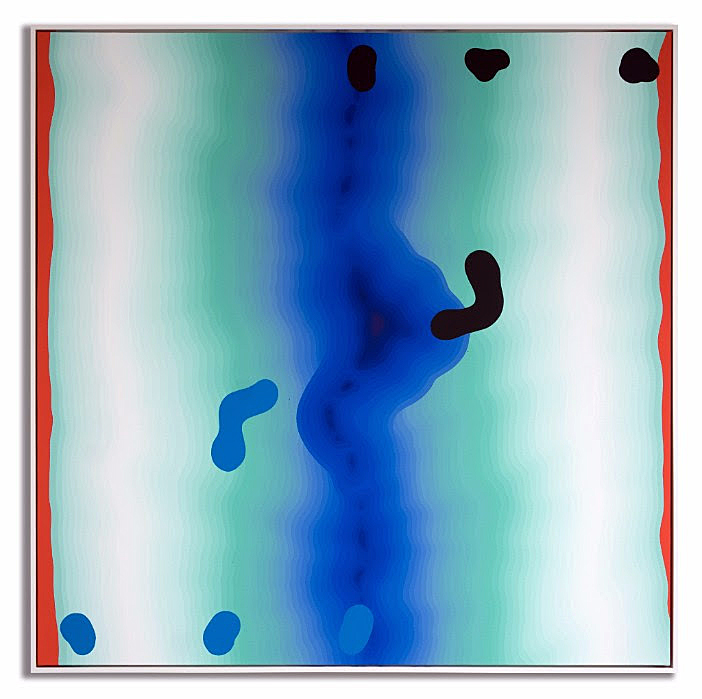

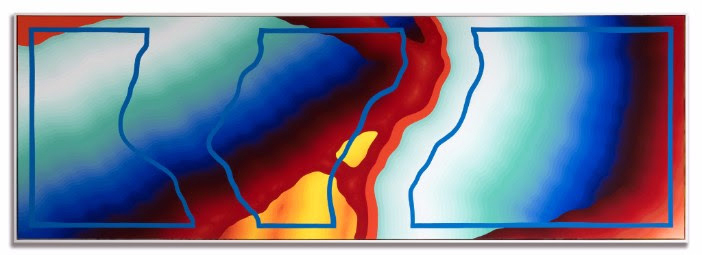

Ellsworth Kelly, as curator, positioned his own works adjacent to Matisse’s, not mingling with them- a nice gesture of deference to a master, as well as a sly, unique lens for perspective. According to the exhibition’s press release, the viewer is meant to see Kelly’s lithographs first, and then approach Matisse as if through Kelly’s eyes. I went in the opposite way, washing up to Kelly’s lithographs dazzled by Matisse. The two artists complement each other like a tall glass of water after a shot of bourbon. As Kelly points out in the above-mentioned interview, his forms are closed- sparing in detail like Matisse, but quieter, humbler, more about shape than movement. They are, in their way, as beautiful as Matisse’s drawings- scaled and composed masterfully, describing plants found in the French countryside with a graceful observance not readily apparent in his more famous paintings. The major difference is that Kelly’s minimalism seems wrought from disciplined restraint, while Matisse’s economy of line erupts, magically, from abandon and delight.

Henri Matisse, Drawing, Large Head, 1949

Matisse Drawings- Curated by Ellsworth Kelly is on view at the University of Michigan Museum of Art November 18, 2017, through February 18, 2018.