Susan Goethel Campbell: Faulty Vision, David Klein Gallery

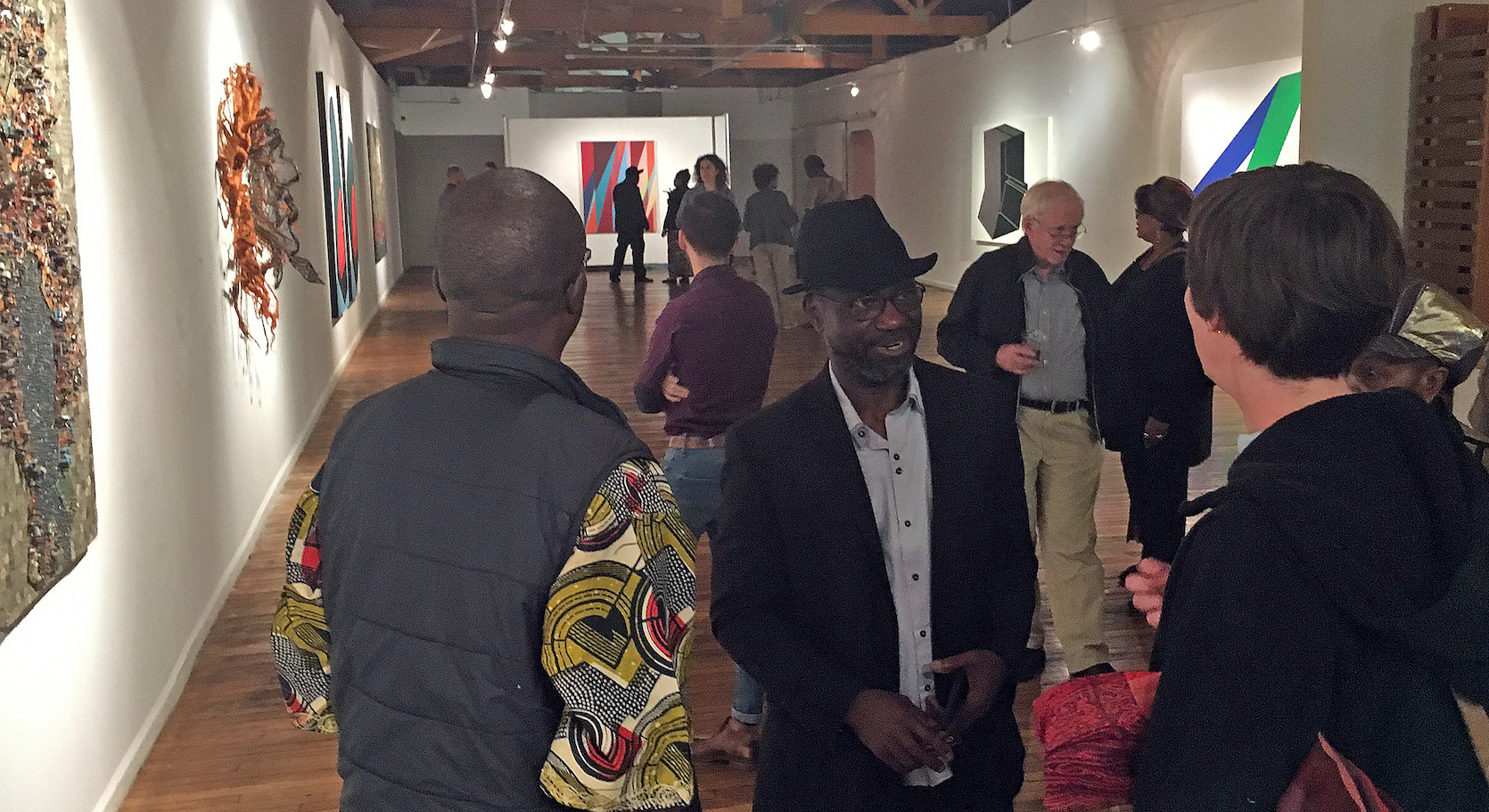

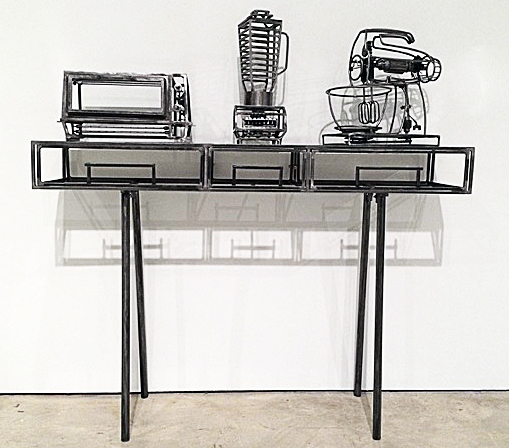

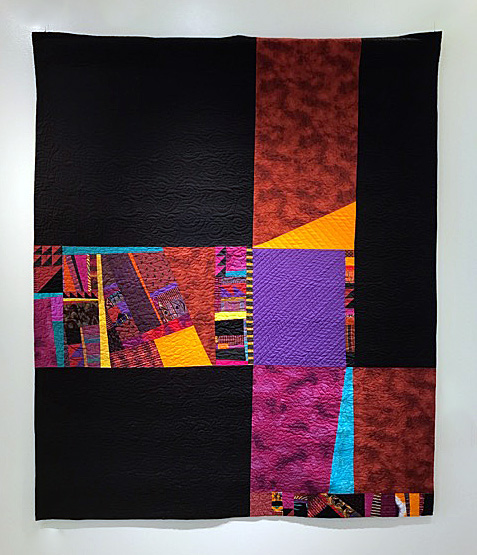

Installation image of front gallery. All images courtesy of David Klein Gallery 2017

Susan Goethel Campbell’s installation “Faulty Vision” currently showing at the David Klein Gallery has all of the ingredients of the mise-en-scene of a surreal film. Like a Japanese garden it is challengingly eye-opening while meditative. In keeping with Campbell’s engagement with both architectural and “natural” space, “Faulty Vision” is designed as a response to the Beaux-Arts architecture of the Klein Gallery itself. The Grand Entrance, to use Beaux-Arts terminology, of the gallery, entering off of Washington Boulevard, Detroit’s premier Beaux-Art avenue, is activated by Campbell’s large, atmospheric black and white dune-scape photos seamlessly embedded into the walls; her uncanny, actual sized, cast earth and grass column echoes the classical Doric column next to it; magically engineered grassy, target-like images float in the middle of the gallery space; and black and white photos of planet-like orbs float around the space, all suggesting a strange landscape indeed. Each of the objects and images has evolved from the trajectory of recent related, but separate, projects that collectively comprise Campbell’s hybrid artistic practice. It is an elegant albeit enigmatic installation to contemplate.

Susan G. Campbell, “Dune No. 2,” 2017, Black and white digital print, 40” x 60”

Trained as a printmaker, it has become a method and process of her practice to see and think in multiple images and variations of those accumulations, as well to consider the processes of the “natural” world (germinating seeds and growth) and of the engineering processes of industrial manufacturing itself that compete with nature. For years now Campbell herself has become a kind of research and development factory, experimenting with organic materials such as seeds, plants, leaves, and even more ephemeral conditions like light, night sky and air itself. The overarching gesture then of “Faulty Vision” is to, it seems, if not challenge, then assay and respond to the symbolic permanence of that Beaux-Arts designed gallery space. Early in the twentieth century, Detroit and most American cities adopted a pared down version of Classical Greek and Roman architectural models, that have historically symbolized the enduring strength and permanence of European culture.

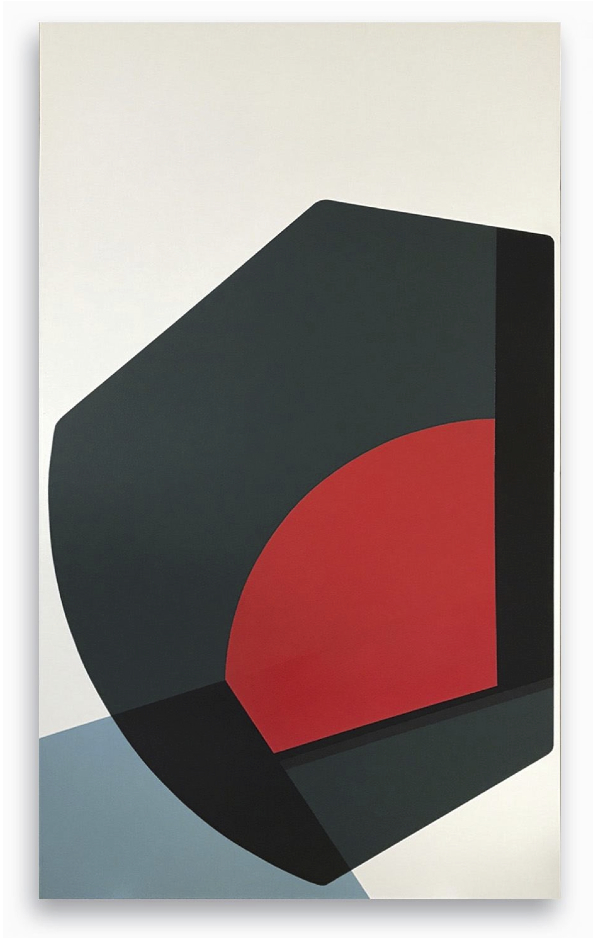

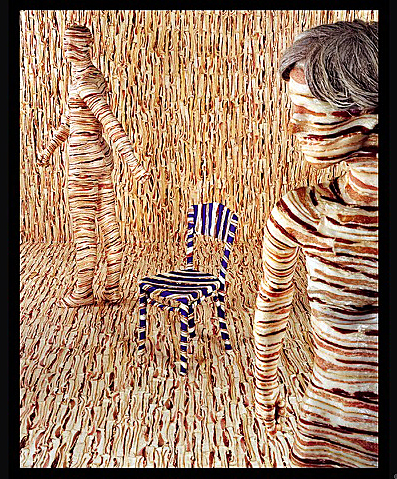

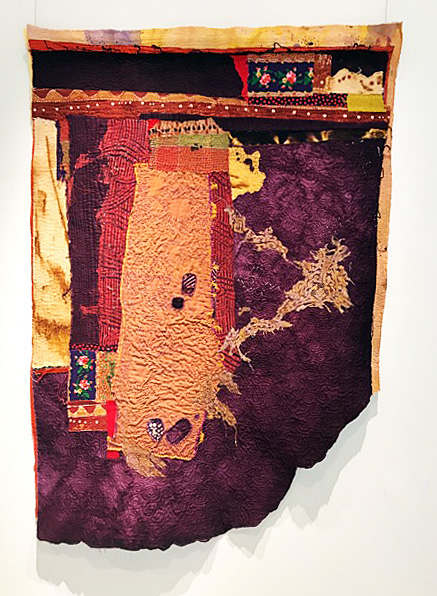

Susan G. Campbell, 4“ Ground no.6 (floor installation), 2017, 51”x51”

When closely examined the stunning earth work sculptures that are installed in the main gallery are all ironically modeled on what were once called “disposable” objects. Campbell’s column is made of hundreds of cast-earth and grass water bottles, grown in molds of the plastic bottles, to form a simulated, fluted Doric column. It is an over-the-top critique of the bombast of classicism and at the same-time beguilingly baroque. Situated in the gallery’s windows facing Washington Blvd., as if window-displays of consumer goods, are stacks of cast-earth and grass cell phones modeled on the evolving i-Phone, 4, 5, and 6 series. (As in nature phones evolve too). And echoing larger engineered earthworks (such as center pivot watering circles in contemporary agribusiness) as in “Ground No.6 (floor installation),” suggesting also ancient Native American Mound-Builder’s “ruins,” as well as many ancient, rammed earth and mud constructions. All of the materials of Campbell’s sculptures are made of natural, decomposable materials and are serious parodies of the plastic and aluminum models.

At one point in a recent talk at the gallery, Campbell alluded to the earth work of artist James Turrell and fantasized an installation of an enormous field of her own cast-earth concentric rings. “I love multiple images of the same thing…like seeing a shelf of the same product in a grocery store.” Repeating any image, such as the cell phone shape or her concentric rings, is one of the basic tropes of modern art (Warhol) and architecture (Mies van der Rohe) and belongs in any discussion of printmaking as well as mechanical reproduction. Repetition seems to insure coherence and a sense of consistency and security, versus the chaos and uncertainty of the of fickleness of nature. Repetition also is the beginning of making a pattern that creates structure and strength.

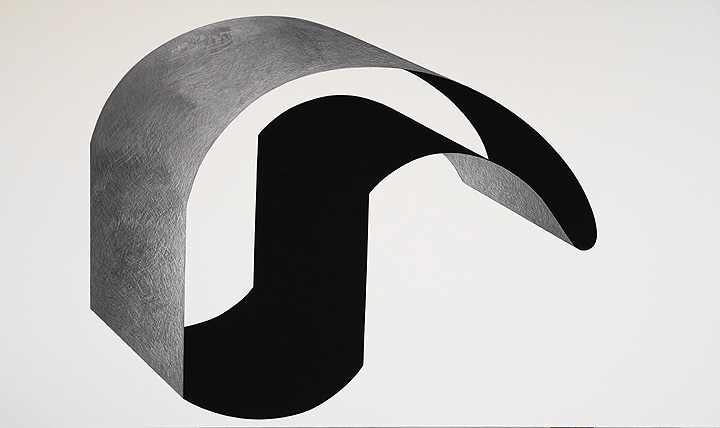

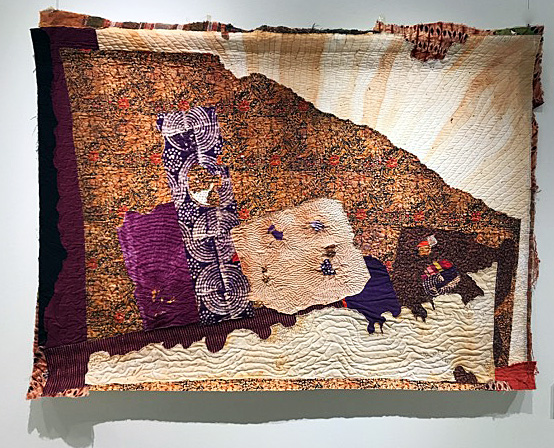

Susan G. Campbell, “Dune No.1,” 2017, Black and white digital print, 40”x62”

In the smaller rear gallery, there is a large B&W photo of a sand dune with two human figures seeming to lean into a struggled walk across the horizon. In the grand scheme of things, of the world around them, with enormous emotional sky overhead and menacing mounds of sand dune and dune grass underfoot, they seem remarkably inconsequential and existentially without destination. In a sense this image is a key to the whole exhibition in projecting a heroic, man against nature, Romantically Sublime, vision, in contrast to the constructed space of the gallery. While this photographed landscape captures the same organic materials as her engineered works—earth and grass, such as in Ground No.6– it is chaotic and foreboding, the exact opposite of Campbell’s built organic world. Three other dune photos, with haunting fog and solitary figures, also suggest a counter to the controlled order of Campbell’s engineered pieces and create a narrative tension to the whole exhibition: nature versus the built world.

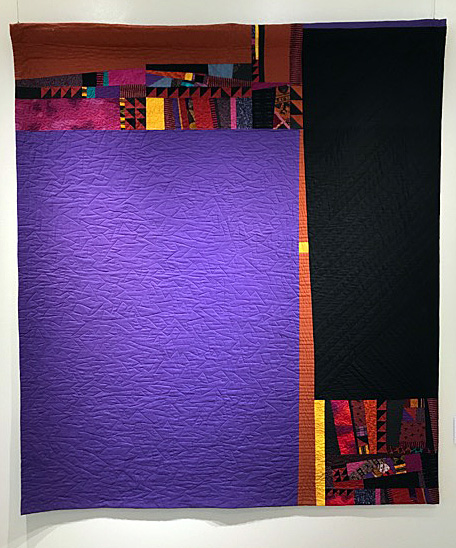

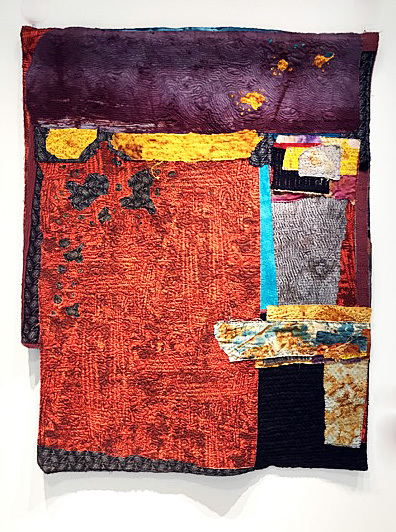

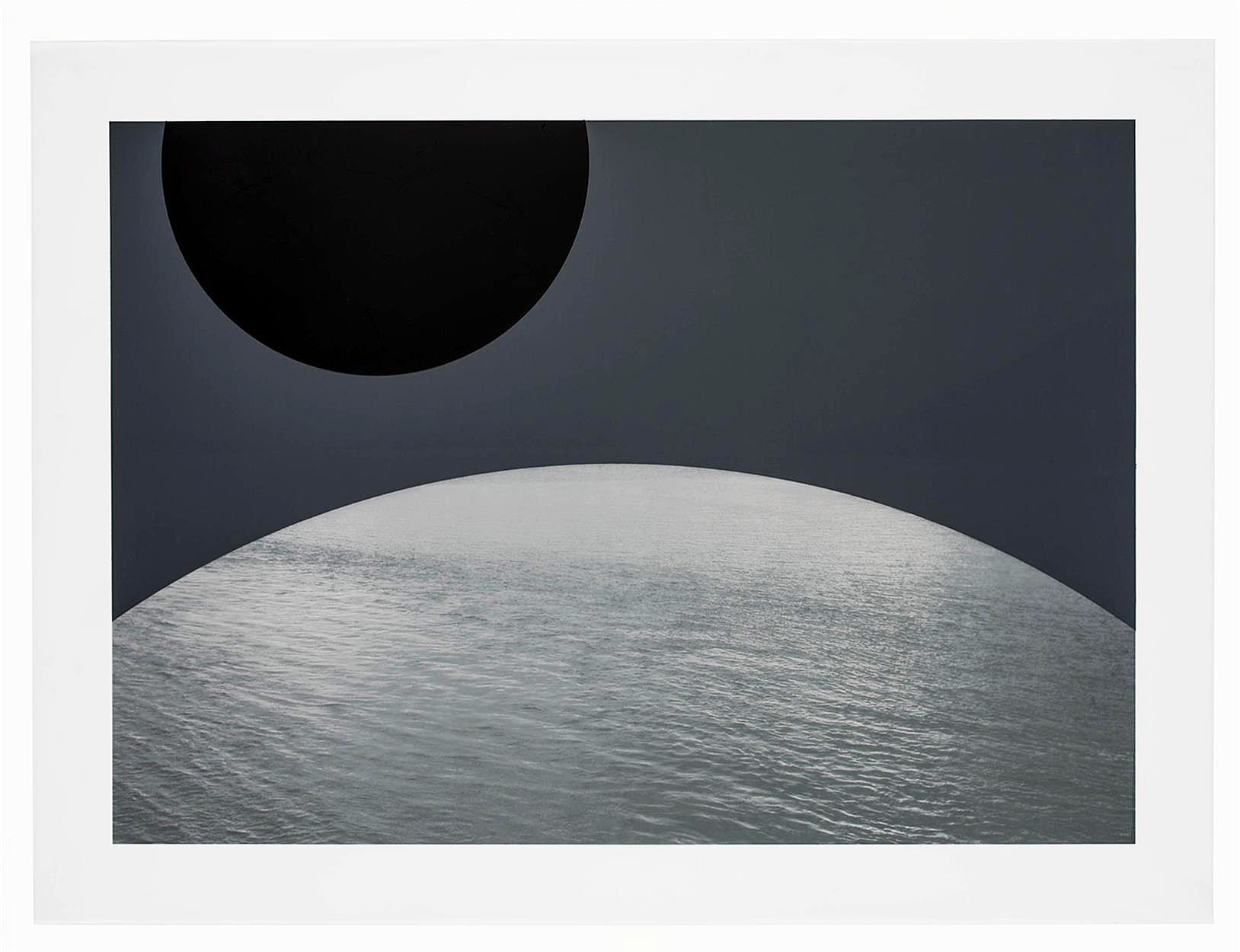

Susan G. Campbell, “Water Planet No. 5,” 2017, Digital print on polyester, spray paint 22 3/4 x 30 5/8″

A third group of images triangulate Campbell’s vision and offer a surreal contrast to the architectural and natural conditions of landscape or environment that determine the rest of Campbell’s projects. The “Water Planets” are a series of images of planet-like orbs pictured as composed of water, floating in a hauntingly empty space. “Water Planet No.5” has two truncated orbs, one eclipsed in shadow and one of water, situated in a matte gray ethereal space. Each “planet” exists in ultimate isolation and, one imagines, can virtually never touch another or conjoin with the other. The “Water Planets” are an uncanny and stunning invention and throw all of “Faulty Vision” into another realm of thought and are superior evidence of Campbell’s considered world.

In “Faulty Vision,” Campbell is responding to an architectural space with its own specific, highly evolved Classical ideology. The David Klein Gallery is not simply white walls upon which to hang her work. The Beaux-Arts history, of which the Klein gallery is a part, is virtually the result of the fantasy of authority and permanence that is western culture. It is the result of a weird evolution and Campbell’s fragile, water bottle, grass and dirt column, circles and i-Phones are a remarkable response to that history. There is an umbrella of ambiguity that protects the complicated equation of “Faulty Vision,” that allows for many readings and wonderings, and Campbell plays on that.