Ubhule Women: Bead Work and the Art of Independence at the Flint Institute of Art

Zondile Zondo. I am ill, I still see Color and Beauty: Jamludi The Red Cow, 2012. Glass beads sewn onto fabric. 49 × 64 1/4 × 2 in. (124.5 × 163.2 × 5.1 cm). Private Collection.

In 1999, two South African women, Ntombephi Ntobela and Bev Gibson, established an artist’s community on a former sugar plantation in the rural outskirts north of Durban. The goal of the Ubuhle (Ub-buk-lay, Zulu for “beauty”) community was to use traditional bead-art as a way for women to develop a skilled trade and become financially independent. Since then, the work created by this small, tightly-knit group has experienced meteoric success and has been shown internationally, including an exhibition at the Smithsonian in 2013. Through the end of March, Ubhule Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence ambitiously fills the spacious Hodge Galleries at the Flint Institute of Art, and is well worth the visit.

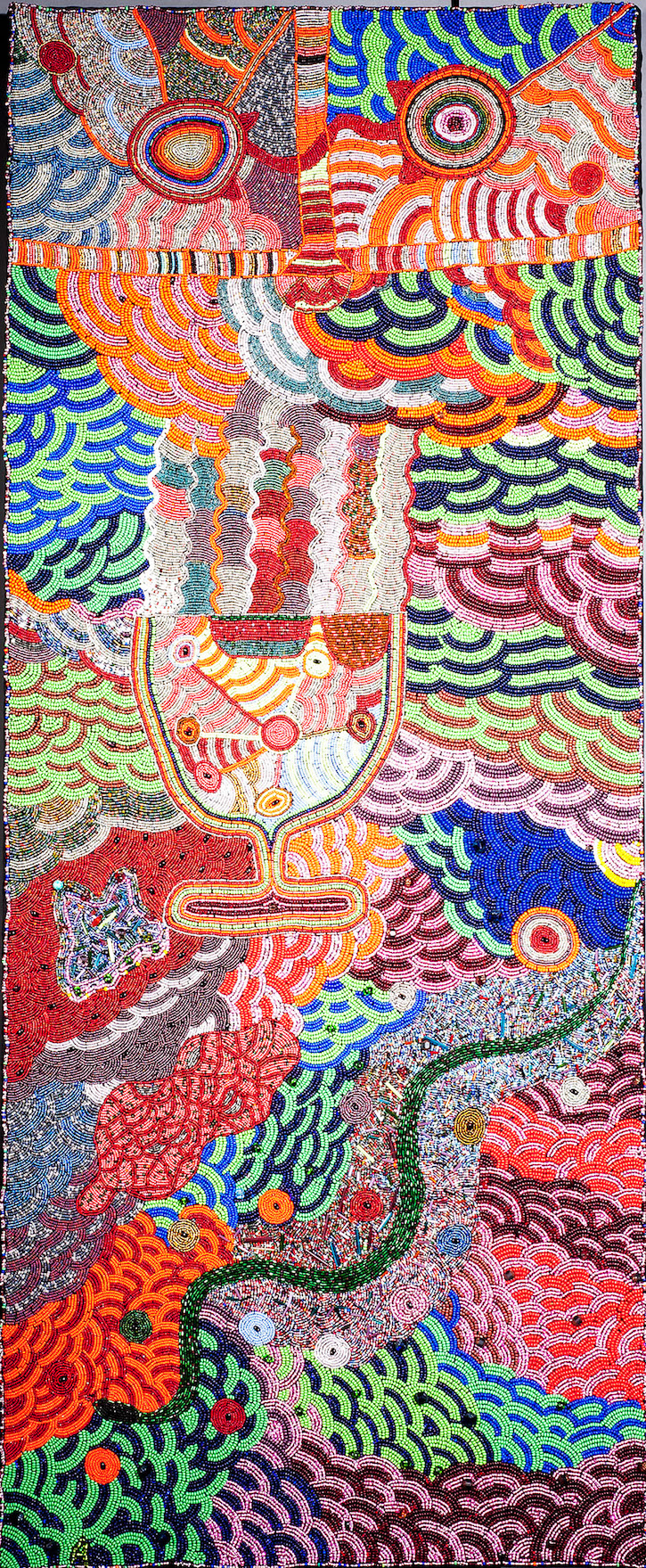

Zondile Zondo. Flowers for the Gods, 2012. Glass beads sewn onto fabric. 51 × 21 3/8 × 2 in. (129.5 × 54.3 × 5.1 cm). The Ubuhle Private Collection.

This is an exhibition that can only be experienced firsthand; the arresting luminosity of these textile and bead-works, much like the ethereal shimmer of light on a Byzantine mosaic, is entirely lost when reproduced in photographs. The Ubuhle women created a modern innovation on traditional South-African bead-art; they stretch textile (ndwango) across a canvass, into which they meticulously hand-sew tens of thousands of infinitesimal Czech glass beads. The completed result recalls Seurat’s pointillism, but enhanced with striking luster as the images reflect actual light. These ndwangos range from figurative to abstract, and the vibrant plains of color deny any sense of illusory depth. Visitors who lean in close will notice the artists frequently applied the beads in a complex array of circular patterns and spirals, another special-effect that doesn’t translate well in photographs.

Ubuhle Women comprises 30 works by five artists, and the subject matter is intensely personal, often making use of abstract symbols to reference autobiographical events. Some works pay tribute to those of the Ubuhle community who have died since its founding from HIV (about half its number); red ribbons are a recurrent motif. The time-consuming process of bead-sewing itself functions as a form of therapy and coping—just one panel can take nearly a year to complete. For the Ubuhle women, beading is both catharsis and a visceral way to make tangible the memories of those lost.

Nontanga Manguthsane. African Crucifixion, n.d. Glass beads sewn onto fabric. 177 1/2 × 275 3/4 × 16 inches (450.9 × 700.4 × 40.6 cm). The Ubuhle Private Collection & Private Collection

The culmination of the exhibition is the ambitiously-large African Crucifixion, a sprawling work comprising seven panels created by seven Ubhule women. Originally conceived as a visual focal-point for the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermartzburg, South Africa, the work is a complex tableau that addresses specific local issues like apartheid and the HIV crisis, as well as broader, universal themes of life, death, and redemption. A suspended golden crucifix dominates the composition, flanked by a menacing Tree of Defeat (replete with vultures, representing politicians who feed off people) and the Tree of Life, comfortably situated in an idyllic, fertile landscape. In the panel depicting Mary and John at the foot of the cross, a white house in the background personalizes the image, uncannily reminiscent of Thando Ntobela’s reductive portrayal of the Ubuhle community in her 2011 work Goodbye Little Farm. The African Crucifixion is a triumphant and virtuosic demonstration of the potential of beadwork, every bit as grand and pathos-driven as an early Renaissance fresco.

Looking at these works, my initial response was to mentally liken them to comparable works of art with which I was already familiar; the bright, smack-you-with-color fauvist paintings of Matisse, for example (and there really is a resemblance). But these ndwangos, as luminous as they are allusive, pugnaciously defy any easy comparison with any equivalent in Western art. Furthermore, they represent the power of art to—in a small way—affect real social change, as demonstrated by the determined effort of the Ubuhle women who, through their craft, achieved financial independence one glass bead at a time.

Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence was developed by the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Washington, DC in cooperation with Curators Bev Gibson, Ubuhle Beads, and James Green, and is organized for tour by International Arts & Artists, Washington, DC.

Flint Institute of Art – through March 2018