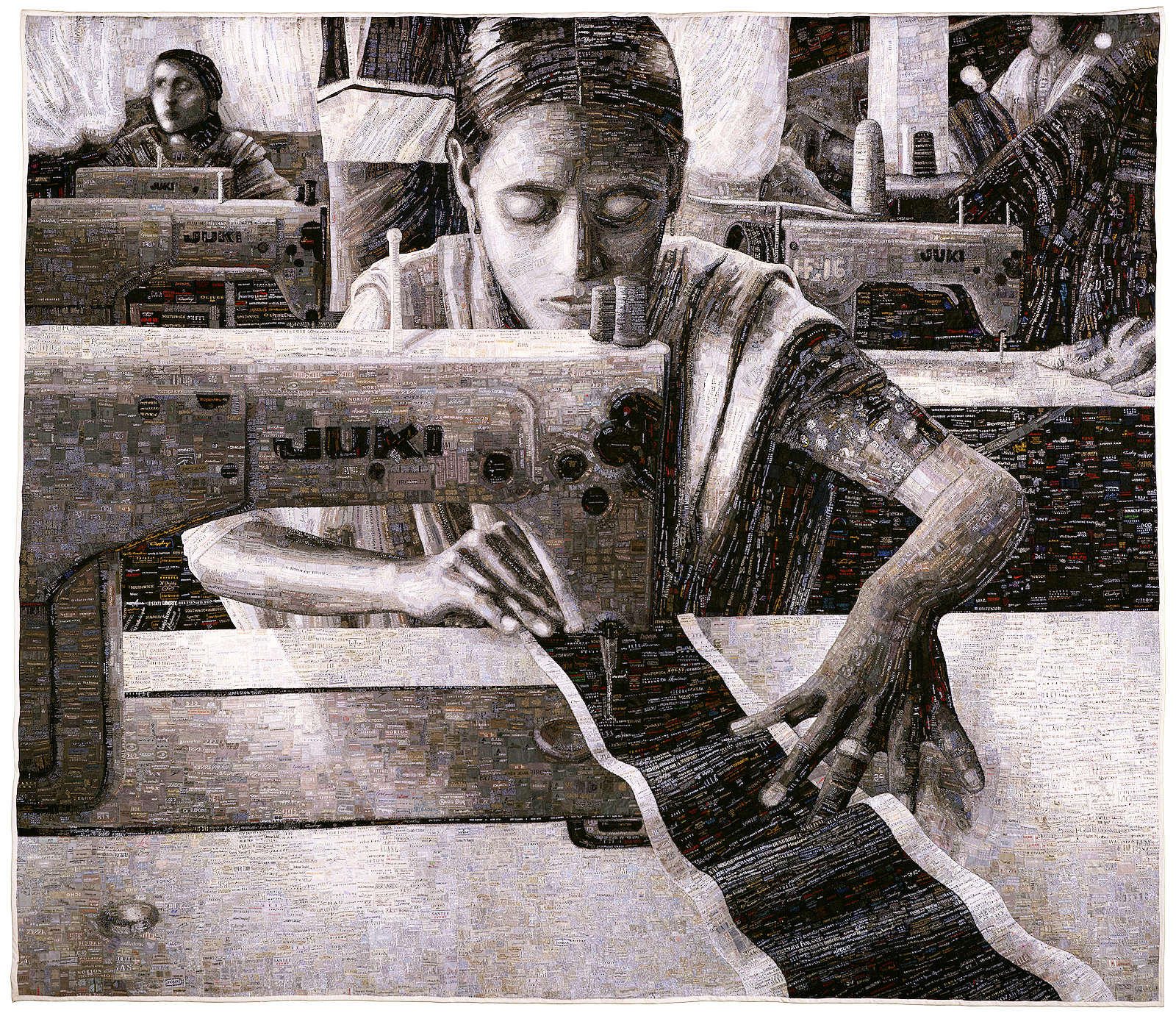

Glass in Four Dimensions @ Flint Institute of Art in the Harris – Burger Gallery

Installation image – Glass in Four Dimensions, Image courtesy of Jonathan Rinck

When Albert Einstein advanced his general theory of relativity, he argued that there was a fourth dimension: spacetime. According to theoretical physicists, spacetime has very physical properties: it can literally warp, bend, and even tear. So can molten glass, of course, and the exhibition Glass in the Fourth Dimension, currently on view at the Flint Institute of Art through March 21, features a selection of glass works from the Studio Glass Movement (the 1960s through the present) which directly or indirectly speak to the concept of the fourth dimension.

The works in this single-gallery exhibition space collectively take playful liberties with the technicalities of what the fourth dimension actually is. Some of these sculptures celebrate the intrinsic weirdness and plasticity of glass (itself described by some physicists as a “new state of matter”). Others evoke Daliesque, other-worldly realms. And some take a more literal approach, directly referencing both time and space.

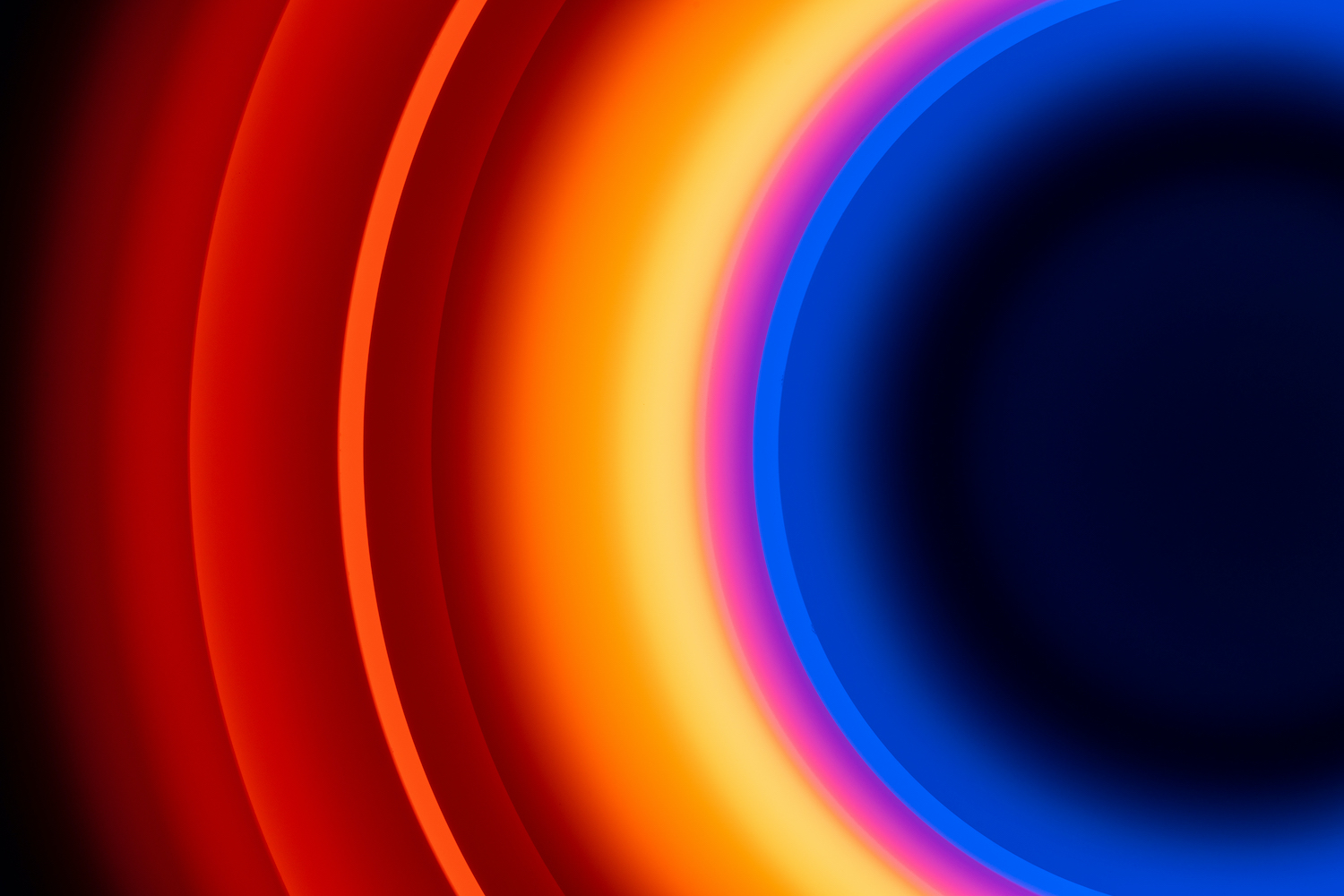

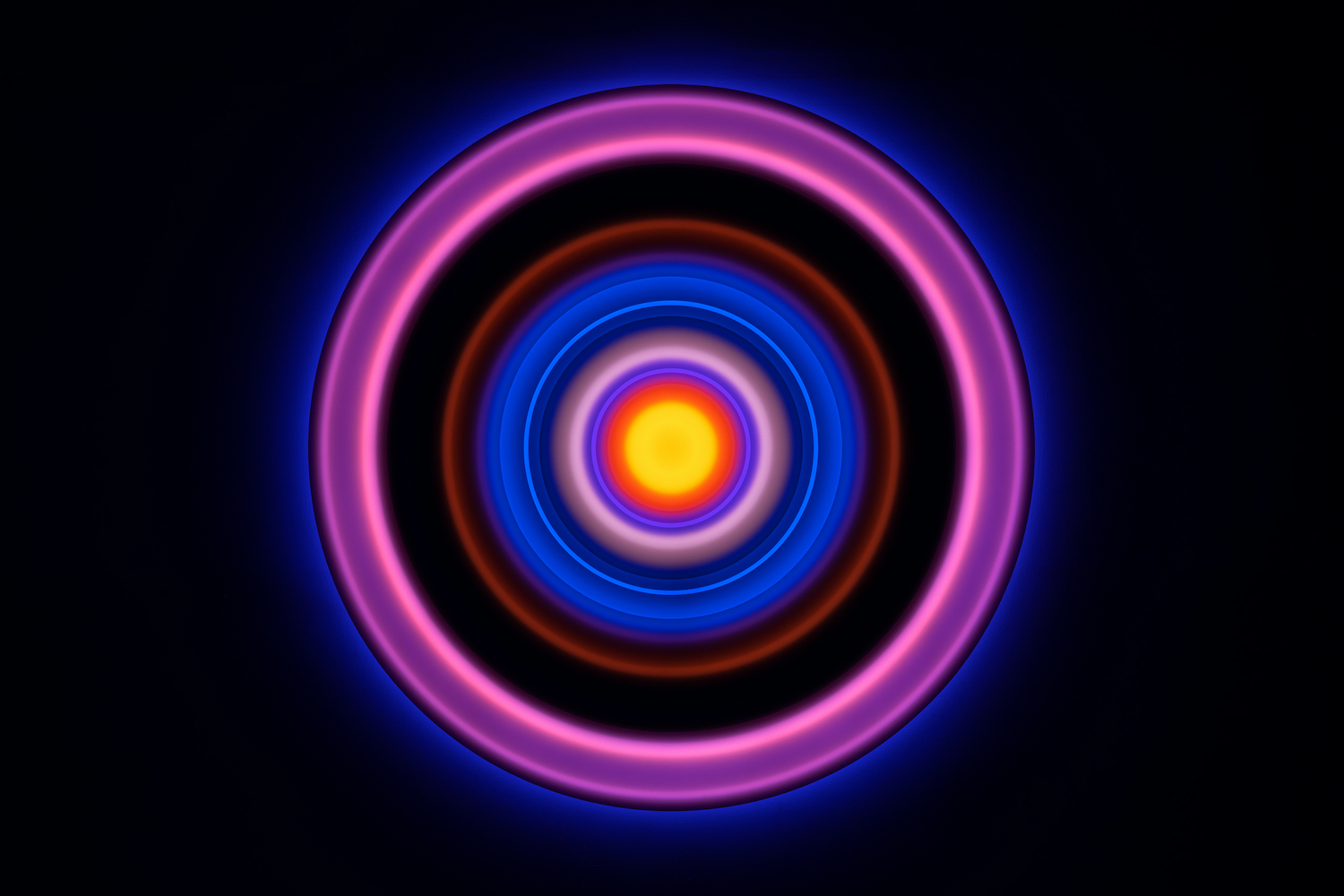

Steven Weinberg, American, born 1954. Fluted Concentrics, 1995. Cast and cut optical crystal 7 3⁄4 x 7 13/16 x 7 13/16 inches. Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, Photography by Douglas Schaible

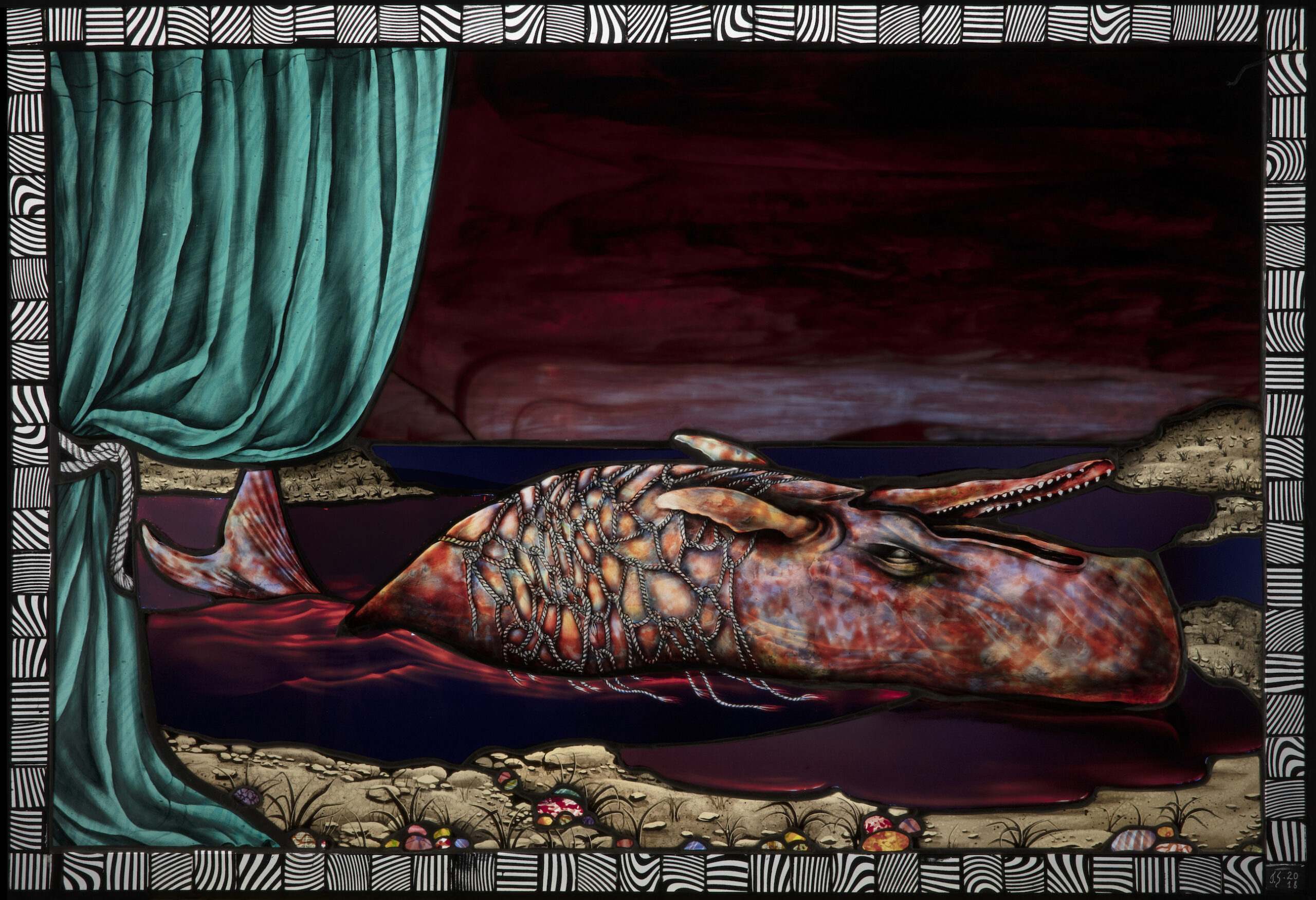

Evocative of some sort of transcendent and other-worldly space, Steven Weinberg’s Fluted Concentrics, is a work of cast and cut optical crystal, inside which exists a set of abstract architectural forms. Though Weinberg’s works are largely inspired by the forms of ancient Mayan architecture, here this little cubic micro-world seems suggestive of the counterintuitive universe of M.C. Escher. Richard Ritter also gives us a sort of micro-world with his Florescence: Series #11, which visually reads almost like a sort of oversized petri dish, within which are emerging biomorphic, organic forms. And Czech artist Petr Hora’s Hadros visually reads like liquid suddenly arrested in time and space, its internal patterns (micro-bubbles that formed when the glass was molten) vaguely reminiscent of a Hubble image we might expect to see of the vaporous membranes of some deep-space nebula.

Petr Hora, Czech, born 1924. Hadros, 2006. Cast and acid-polished glass. 18 3⁄4 x 15 1⁄2 x 4 3⁄4 inches. Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, Photography by Douglas Schaible

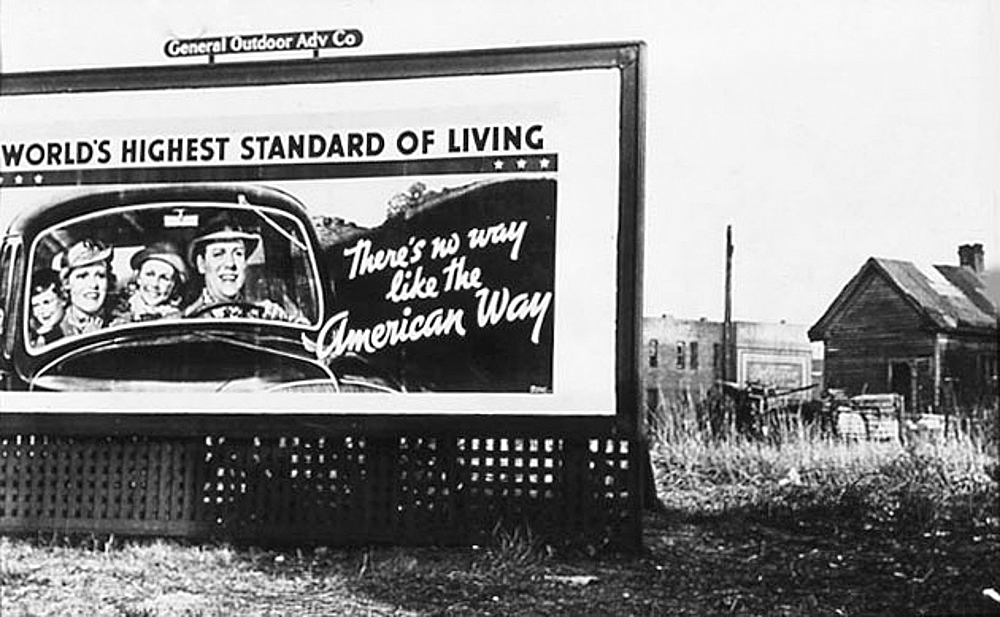

Some of these works subtly imply the passage of time through their form and structure, such as an ensemble of undulating Dale Chihuly bowls, which characteristically rest inside each other much like Russian Matryoshka dolls; the transition from small to large is suggestive of growth over time, or perhaps expanding ripples or sound waves. Though Chihuly’s style couldn’t be more different, its effect responds well to Tom Patti’s Four Ringed Echo, a cuboid sculpture comprising layers of glass which contain a set of vertically stacked rings expanding upward and outward, again implying both time and movement, much like successive frames of stop-motion photography. Both works also directly speak to the ambiguity of the nature of glass, which straddles the boundary between liquid and solid.

But at its most literal, the fourth dimension is a reference to the interconnectedness of both space and time, and some of these works address this directly. Admittedly, all sculpture does this to some degree. A painting or photograph can be taken in by the viewer instantaneously, but sculpture exists in three-dimensional space, and must be appreciated in 360 degrees; the viewer must move around it, incorporating the element of time. But unlike many traditional sculptures, here, largely because of the reflective nature of glass, these works surprisingly transform as we move around them.

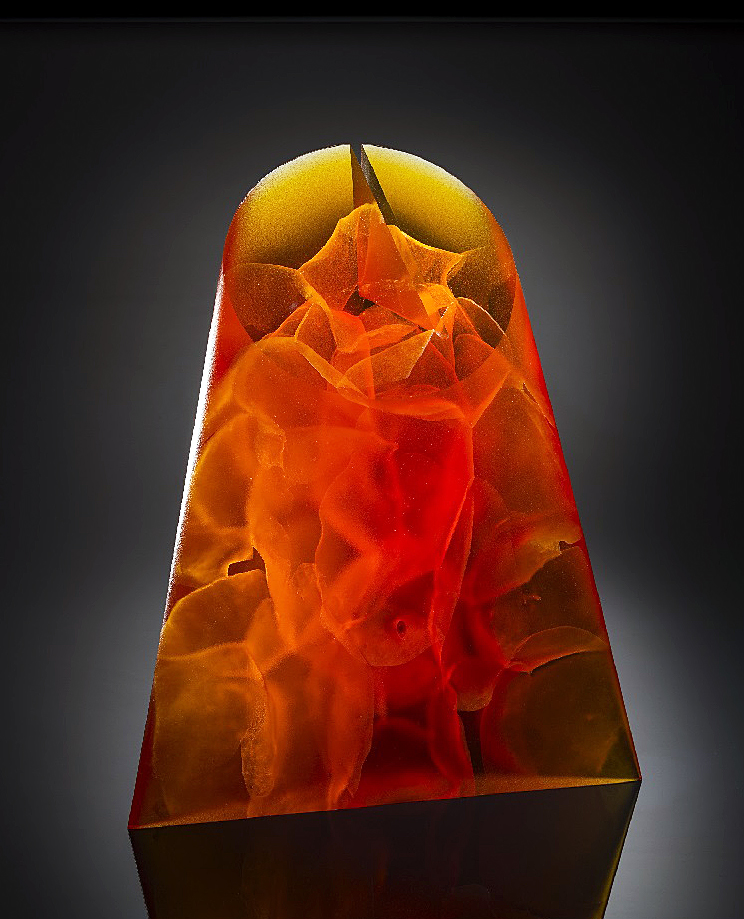

Some of these sculptures do this in dramatic fashion. Just take a look at Czech artist Bohumil Eliás Sr.’s Silent Inhabitant. It’s a cuboid composite of layers of square plates of glass; when viewed from the side, it’s a mostly transparent cube. But slowly move 90 degrees to the front, and a blue, three-dimensional floral form enclosed within suddenly materializes, the result of thin layers of paint applied by the artist on each successive layer of glass. A similarly dramatic transformation occurs with Slovakian artist Yan Zoritchak’s Space Messenger. Here we find a wedge of relatively empty and transparent glass that suddenly fills with surprising and counterintuitive shapes, forms and colors as we move around it.

Yan Zoritchak, Slovakian, born 1944. Space Messenger, 2002. Cast glass with copper patina and gold leaf. 19 9/16 x 16 15/16 x 5 1/8 inches. Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation. Photography by Douglas Schaible

As for the theoretical physics behind Einstein’s revelations regarding spacetime, I’ll never understand them, though I do find the fourth dimension fascinating with the help of a good NOVA documentary. Glass in the Fourth Dimension, however, is both welcoming and accessible. And much like the rest of the permanent works on view at the FIA, this exhibit makes abstract art enjoyable to those who might not generally consider themselves fans of abstract art. There’s an undeniable craftsmanship and polish on display, and all these works are undeniably beautiful. Furthermore, the time-based element to this show emphatically makes the case that art is best viewed firsthand (and over time), and not just instantaneously as an image online or in a book– a compelling reason to come see this exhibition in person.

Glass in Four Dimensions @ Flint Institute of Arts through March 21,2021