Rachel Ruysch, Flowers in a Glass Vase, 1704, (collection of Detroit Institute of Art) photo courtesy of Toledo Museum of Art.

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), a prolific painter of still life whose canvases combined scientific knowledge with breathtaking beauty, achieved unprecedented fame and acclaim during her long creative career. She was the first woman to gain membership in The Hague painters’ society and was one of the highest-paid artists of her day; her crowning achievement was her appointment as court painter to Duke Wilhelm, Elector Palatine in Düsseldorf in 1708. Now, in this first-ever major exhibition of her work, “Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art,” the Toledo Museum of Art, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston collaborate to bring her back into focus from recent relative obscurity.

Ruysch was born at the approximate high point of the Dutch colonial empire, when explorers, scientists, and traders created a global network of outposts and colonies, including vast holdings in North and South America, the Caribbean, southern Africa, mainland India, and the Far East. The exhibition celebrates the burgeoning body of scientific knowledge that came with these explorations and contributed to the voracious appetite of the Dutch bourgeoisie for so-called “flower paintings.”

Rachel Ruysch, Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Stone Table Ledge, 1690s, oil on canvas (Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign) photo, K.A. Letts

Like many female artists, Ruysch became a professional artist through family connections which, in her case, included numerous prominent scientists, artists and intellectuals. Her father was an especially helpful influence. Frederik Ruysch, a noted anatomist and botanist, was much admired for his life-like taxidermy which included human infants, among other specimens that might now seem bizarre to modern eyes. Ruysch herself assisted in the preparation of these biological and botanical artifacts, an experience that must have proved useful in her later work as a painter of flowers, birds, and beetles. Her father’s lavishly illustrated Thesaurus Animalum (a copy of which is on display in this exhibition) was painstakingly accurate and extravagantly fantastical, vividly showcasing the aesthetic attitudes of an era in which science overlapped seamlessly with religion and art.

In acknowledgement of Ruysch’s budding talent, she was apprenticed at 17 to the well-known still life artist Willem Van Aelst, several of whose paintings are on exhibit here. Her early paintings show that she had absorbed his elegant way with flower arrangement along with an interest in compositional asymmetry.

Rachel’s sister Anna was also an accomplished flower painter, though not nearly as successful as her illustrious older sibling. The two appear to have collaborated with and copied from each other, as can be seen from canvases that share individual elements and sometimes whole compositions. Anna’s obscurity compared to Rachel’s can perhaps be explained by her habit of seldom dating or signing her work.

Clearly many of the artists working in the still life genre felt no compunctions in borrowing from or even copying the work of others. A particularly interesting cross-pollination of Ruysch’s work with her fellow artists is her 1686 painting Floral Still life, in which she copies, verbatim, the right side of Jan Davidsz de Heem’s 1660 painting Forest Floor Still life with Flowers and Amphibians. De Heem’s composition includes a landscape–complete with ruins–on the left side of the painting (a common compositional device of the time, but one which Ruysch herself seldom employed.)

Michiel van Musscher and Rachel Ruysch, Rachel Ruysch 1664-1750, 1692 oil on canvas, (Metropolitan Museum of Art) photo image: K.A. Letts

As she gained experience, Ruysch’s unique style and superior craftsmanship sparked recognition. Often a strong diagonal ran through her paintings and whiplike stems and tendrils moved the eye around the composition. She placed the lighter colored blossoms in the center of the painting, with darker colors arranged around the periphery, fading into shadow.

Ruysch’s paintings were particularly notable for the many small living creatures that inhabited them. She could almost as easily be called a painter of invertebrates, amphibians and reptiles as a flower painter. Her compositions could be considered pastiche, as many of the flowers and animals depicted would not have co-existed in nature.

The exhibition begins in an octagonal gallery of the museum and features a map of Amsterdam, the port city in which Ruysch lived and worked throughout her life. The location of friends, family and professional peers are included and paint the picture of a closely connected community of like-minded intellectuals and artisans. Nearby, a timeline with dates documenting the artist’s life provides context for her work alongside important historical events of the time.

From there, the design of the exhibition is circular, with paintings arranged around the periphery of the galleries from Ruysch’s earliest canvases alongside artwork by influential fellow artists, through her subsequent, highly successful career and culminating in her appointment as court painter to Duke Wilhelm. A few of her late paintings, equally skilled, but lighter in tone and less ambitious in scale (in line with emerging tastes in the mid 18th century) round out the extensive collection.

Rachel Ruysch, Posy of Flowers, with a Tulip and a Melon, on a Stone Ledge, 1748, oil on canvas (private collection, Switzerland) Photo: K.A. Letts

An impressive “cabinet of wonders” located in the central gallery gives some idea of the variety of newly discovered plants and animals that fascinated artists of the time and often appeared in their paintings. Preserved specimens of beetles, butterflies, reptiles and amphibians share space with published material describing their physical features and life cycles. There are, as well, drawings and dried specimens of exotic plants such as the carrion flower (Orbea variegata) and devil’s trumpet (Datura metel).

Jurriaen Pool II (Dutch, 1666-1745) and Rachel Ruysch, Juriaen Pool II with Rachel Ruysch and Their Son Jan Willem Pool, 1716, oil on canvas (Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf) Photo: K.A. Letts

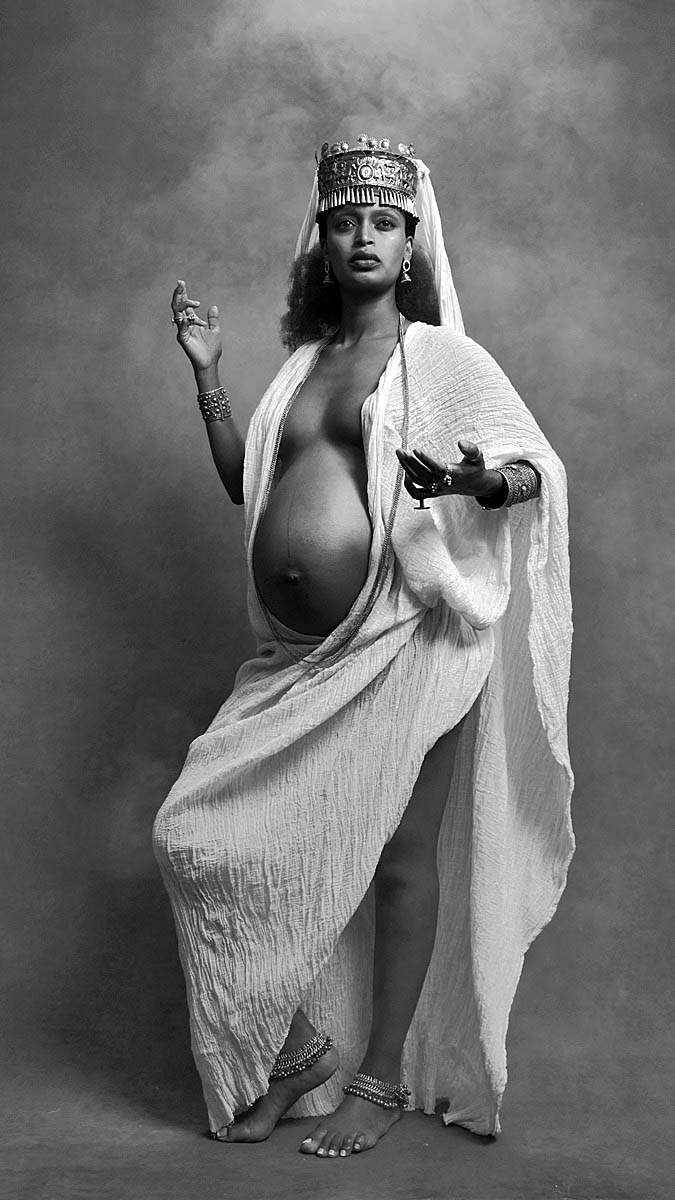

Two portraits of the artist are included in the exhibition. In the first, by Michiel van Musscher, with floral additions by the artist herself, was painted in 1692 as Ruysch was becoming well known but not yet at the zenith of her career. The second, painted by her husband Jurriaen Pool in 1716 (and also including floral painting by Ruysch) was intended as a gift for their patron Duke Wilhelm, though it appears he died before it could be delivered. The child in the picture is Willem, named after the duke, one of the couple’s eleven children–of whom 3 survived.

It would be difficult to overemphasize the esteem in which Ruysch was held during her lifetime, making it all the more puzzling that her reputation fell into eclipse after her death. Johan van Gool’s two-volume survey of prominent Dutch artists, written in 1749, included a comprehensive entry on Ruysch that ran to 24 pages. It was one of the most complete biographies of a female artist prior to modern times and is still the most important source of information on her life and work.

Many enraptured verses were written in honor of the eminent painter, twelve of which were gathered into a volume published posthumously by her son Frederik Pool. A stanza from a 1749 encomium by Lucretia Wilhelmina van Merken sets the tone:

Why do you, fascinated songstress,

So fix your eyes in marveling raptness

On Rachel’s art, her divine prowess?

Thank her for all the work you see…

You’re silent. Is your tongue too weak?

I understand, yes, Poetry

Is dumb when th’ Art of Painting speaks.

Rachel Ruysch, Posy of Flowers with a Beetle, on a Stone Ledge, 1741, oil on canvas, (Kunst Museum, Basel) photo courtesy of Toledo Museum of Art.

“Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art” was recently seen at the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, and will be on view at the Toledo Museum of Art until July 27, 2025. Thereafter, the exhibition travels to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (August 23, 2025-December 7, 2025.) Selldorf Architects is the Toledo Museum of Art’s exhibition design partner for this exhibition. A note: I want to thank my gallery companion-for-the-day, art historian Pam Tabaa, many of whose perceptive observations have found their way into this review.