Family Ties, David Klein Gallery, Detroit, installation, photo by Samantha Bankle Schefman and all other images courtesy of David Klein Gallery

The four artists in Family Ties, now on view at David Klein Gallery in Detroit through August 6, demonstrate a kind of taxonomy of relationship—a way of claiming kinship while comparing and contrasting thought processes, techniques, and materials. As in any family where resemblances like the arch of an eyebrow, a laugh or a sense of style can demonstrate common ancestry, these artists share ways of making and thinking that illustrate the complex interaction of their shared, yet distinct histories.

Ceramicist Ebitenyefa Baralaye, who organized the show, says in his curatorial statement:

Family Ties touches on the multi-layered bonds that connect our given and adopted family members, friends, and community. These bonds are manifested in traditions, shared history, common spaces, and elements of identity encompassing everything from the rituals and patterns of styling hair, the particulars of gathering places for meals, and the textures and shades that mark bodies.

Ebitenyefa Baralaye, Grace, 2022, stoneware, slip, 21” x 14” x 14” photo: courtesy of David Klein Gallery

Ebitenyefa Baralaye, Aishetu, 2022, stoneware, slip, 23” x 13” x 13” photo: courtesy of David Klein Gallery

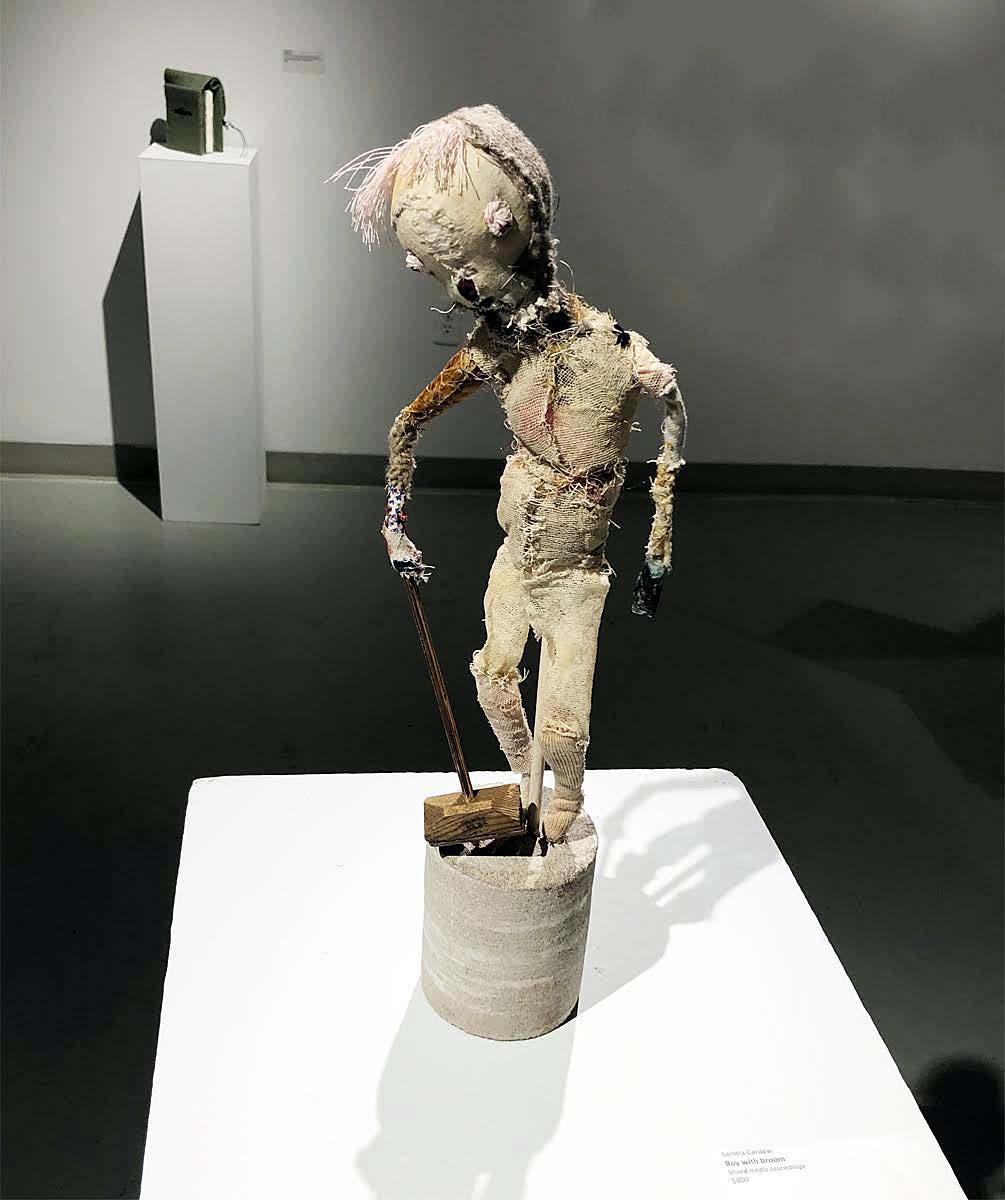

Baralaye sets the tone of the exhibition with his 4 compact yet monumental stoneware heads. They are vessels turned upside down and presented as stylized sculptural portraits. These chunky heads bear a passing resemblance to folk art stoneware face jugs traditionally made by African American slaves, re-purposed to celebrate Baralaye’s female ancestry. There is an element of affectionate caricature here, as well as a liveliness in the slight irregularity of their coiled clay construction. Grace and Anna depend mostly upon the surface application of rolled clay on unadorned fired stoneware for their features, while with Apreye and Aishetu, Baralaye does a particularly masterful job of balancing the three-dimensional low relief surface detail with painted-on black markings–no mean feat.

Shea Burke, Vessel Portrait III, 2022, porcelain, glaze, 10” x 8” x 5” photo courtesy of David Klein Gallery

Shea Burke, Clothed Vessel, 2022, brown stoneware, porcelain, glaze, 20” x 15” x 15”

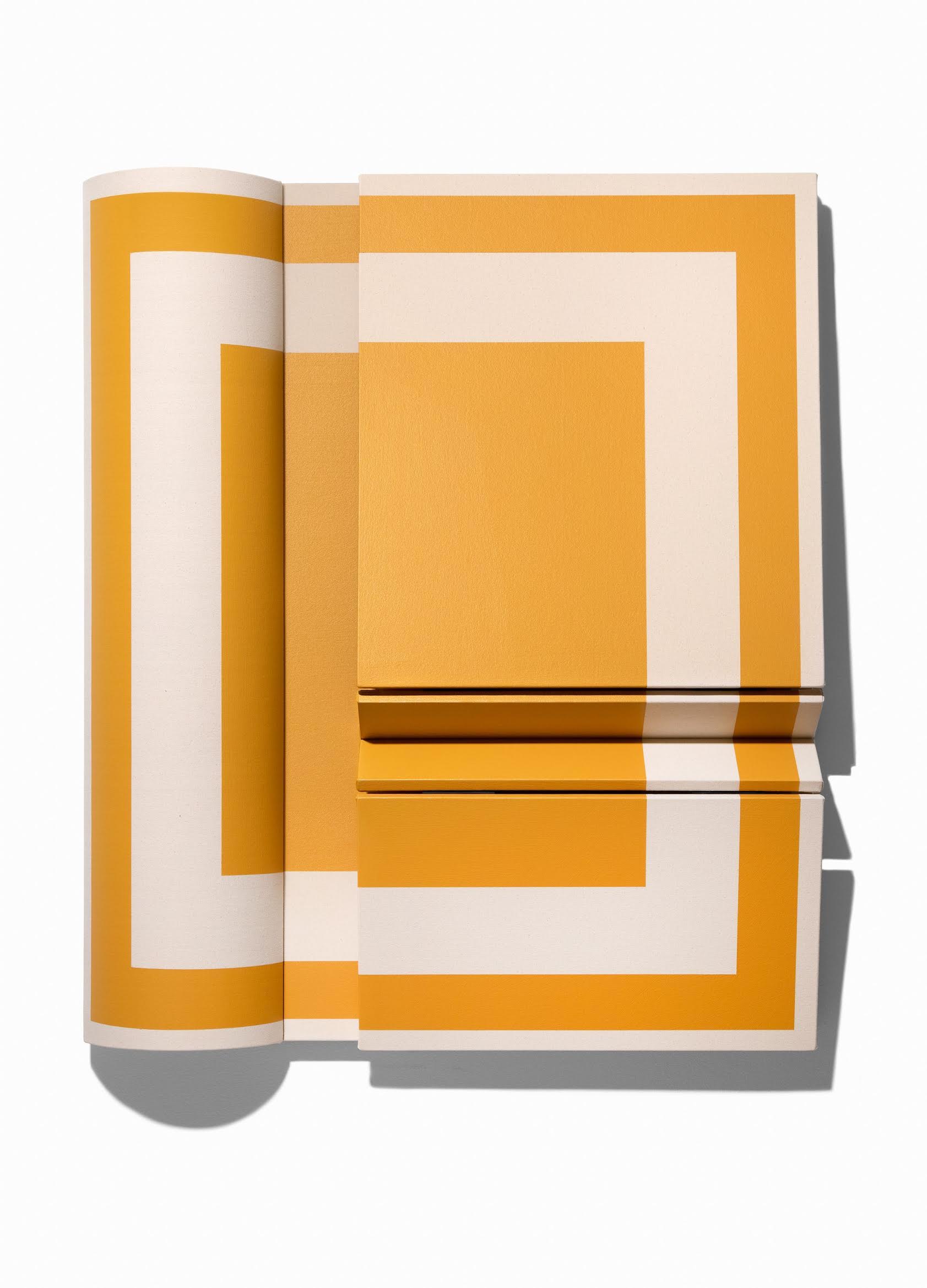

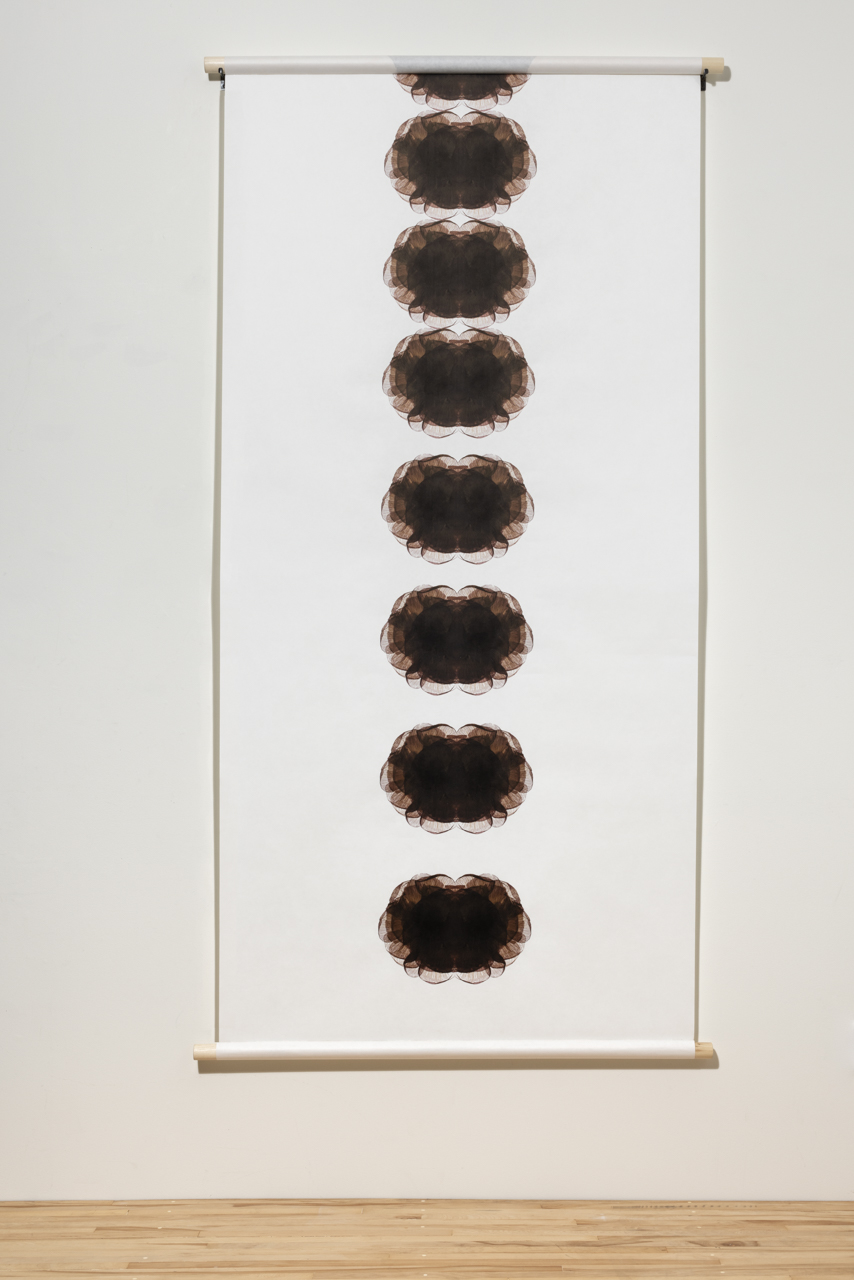

Shea Burke, a ceramic artist from Rochester, New York, shares some of Baralaye’s methods and themes; they use coil construction to build Vessels, Portrait I, II and II, but the coils have escaped the constraints of the classic shapes to suggest wild, snaky topknots of exotic ceremonial headdresses. The artist places particular importance in the temporal process of building, layer upon layer, an object that is a record of time’s passage. “While coil-building I shape the vessel as a place to put the things that slip through our fingers. There is comfort in the idea of having a place to store what we struggle to hold onto: memories, traditions, and moments that are eroded by time,” they say.

Things take a homely turn with Burke’s earthily tactile, coiled and pinched vessels, contrasted with slick, shiny porcelain sheets draped over and around, a kind of metaphoric clothing for the fleshy clay.

Patrice Renee Washington, Onyx Peak, 2022, glazed stoneware, concrete, 36” x 15” x 15”

Patrice Renee Washington, Dirty Jasper, 2022, glazed stoneware, 20.5´x 13” x 13”

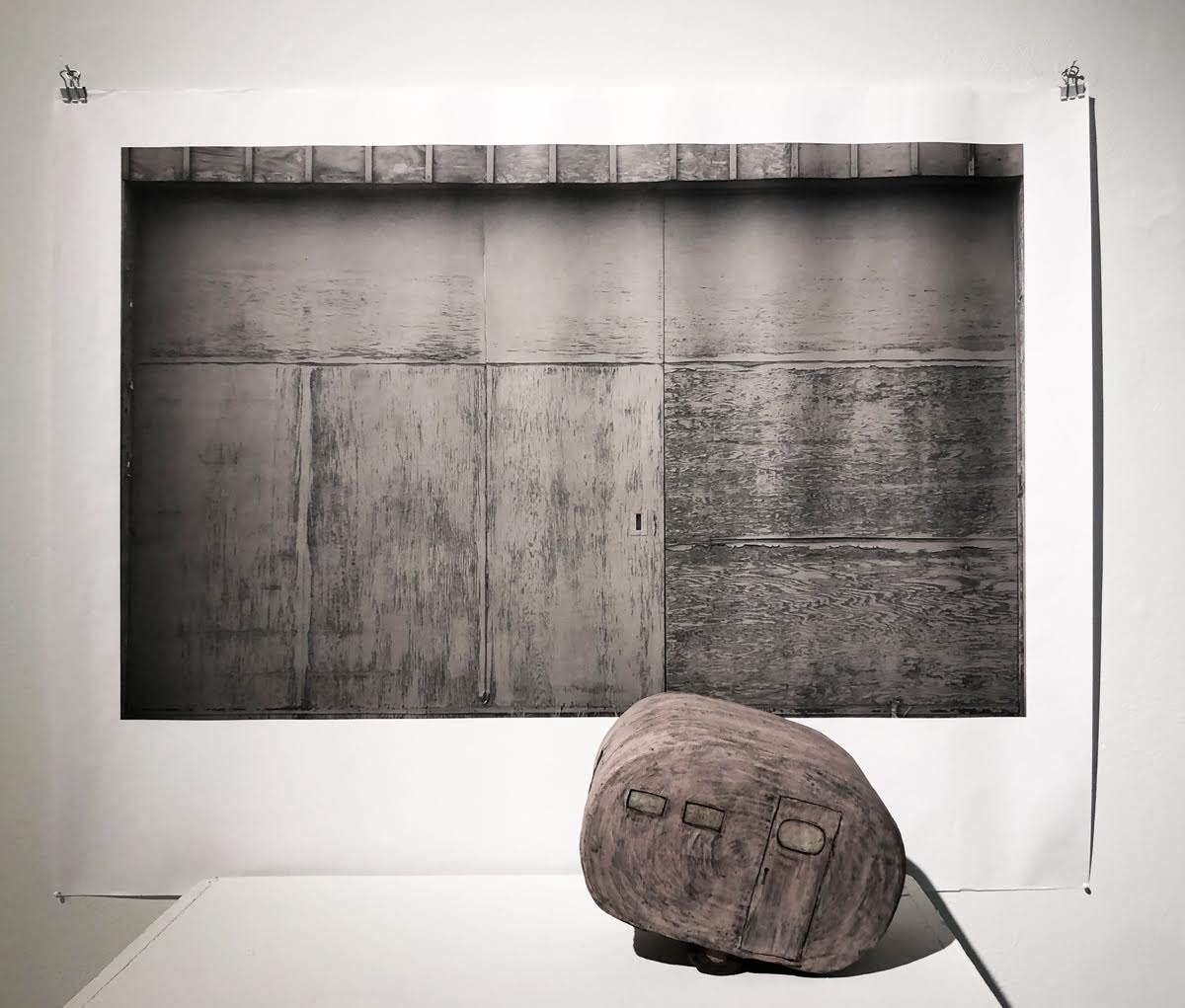

Formal family resemblance continues in the work of Patrice Renee Washington, originally from Chicago, but now living and working in Newburgh, New York. She hand-builds her pagoda-shaped vessels and decorates them with twisted and braided clay applique reminiscent of African hair weaves. The gray color and pointy tops of Onyx Peak and Dirty Jasper take these vessels into the realm of fantasy architecture—or perhaps they are reliquaries. A hidden meaning may be contained in their interior, but it remains inaccessible, mysterious.

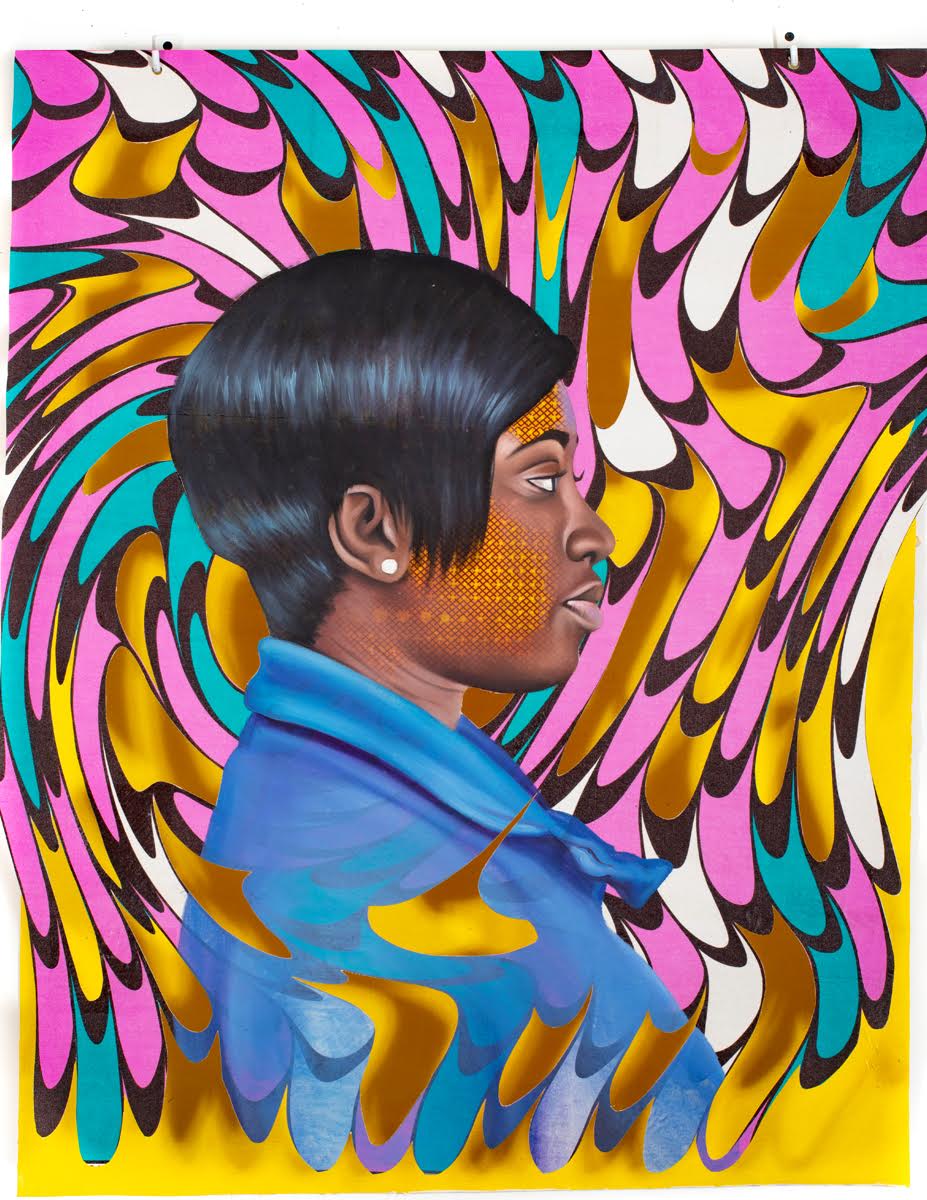

Patrick Quarm, Royal Ama, 2020, mixed media, oil and acrylic paint on African fabric, 65” x 54” photo: courtesy of the artist

Patrick Quarm, The Obverse, 2020, mixed media, oil and acrylic paint on African print fabric, 43” x 33” inches photo: courtesy of the artist

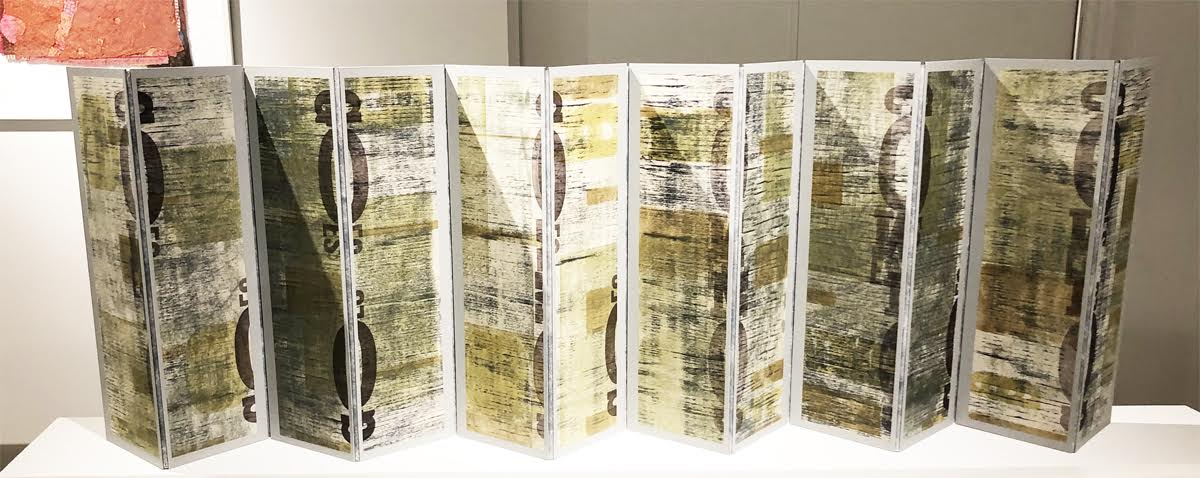

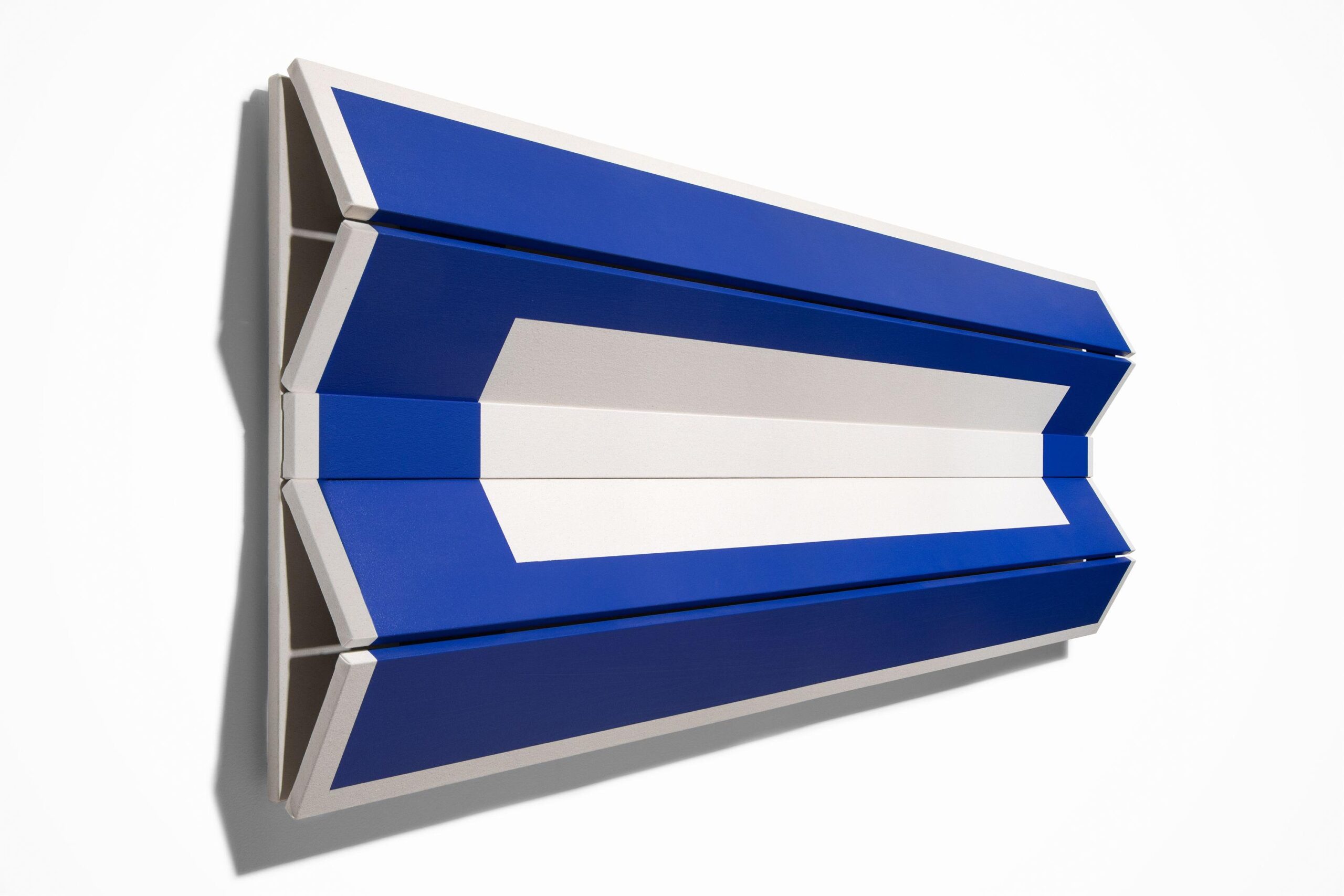

To this otherwise intimately-scaled collection of three-dimensional ceramic pieces in subdued earth-tone colors, Ghanian painter Patrick Quarm adds color as well as the implication of a broader relationship of the artists in the exhibition to the family of African and African American artists worldwide. In relational terms, Quarm could be called a cousin to Kehinde Wiley and Yinka Shonebare, both of whom use the patterns of African textiles and brilliant color to tell complex stories of European colonialism and the African diaspora. His contribution to the cultural conversation is a thoughtful yet intuitive visual analysis of the complex interactions, some positive and many not, of civilizations at their point of contact.

Quarm’s paintings are acts of synthesis, weaving veils of pierced, painted and patterned fabric into a meaningful whole from the disparate elements of his past. Stories of his father’s life in colonial Ghana are added to his own experience as an inhabitant of cultural and social spheres in Africa and the U.S. Many of Quarm’s pieces feature separate sheets of painted fabric loosely fluttering from battens which, viewed from the side, look three dimensional. But from the front they coalesce into a unified composition, perfect metaphors for his aim to create a coherent identity from the diverse and sometimes antithetical parts of his history. He says of his work, “My task or duty as an artist is to strip each layer after the other to bring clarity, to understand the past and how the past shapes the present.”

Not everything about any family—or this family of artists–can be known. There is an interior conversation among these four that must remain a mystery outside its sacred circle, even as it nourishes the creativity of its members. But Family Ties gives us an intriguing intimation of the usually unseen lines that connect them. As Baralaye says, “Family ties are a reminder of the commitment and the persistence of connection even in hard times and through complicated realities.”

Family Ties, on exhibition at the David Klein Gallery, through August 6, 2022.