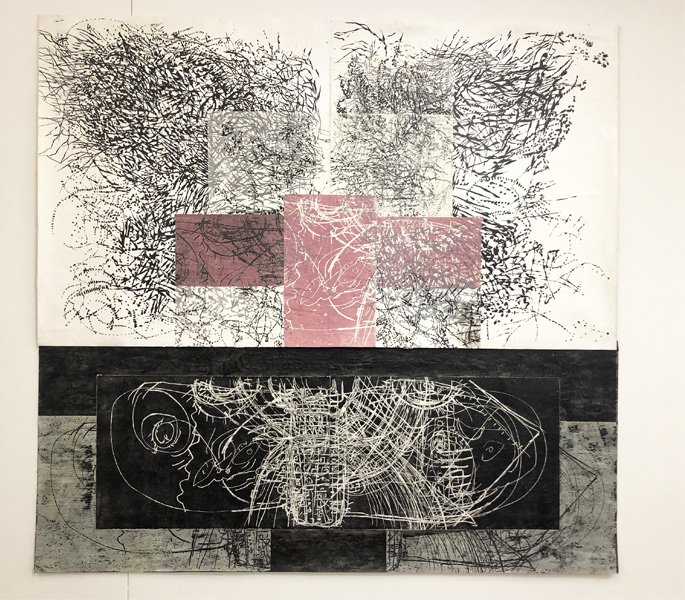

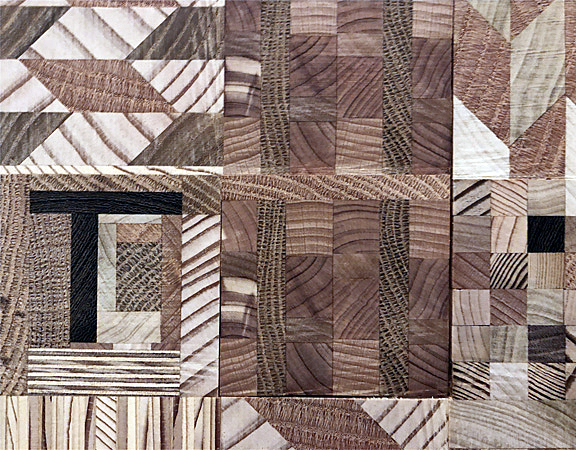

Installation image, Carrie Moyer and Anke Weyer, David Klein Gallery image courtesy of Samantha Bankle Schefman.

We live in an age of attention deficit disorder. Recent studies have shown the average amount of time that the art museum visitor looks at an artwork ranges from 15 to thirty seconds, long enough for a selfie to document that we are in the same room, if not in the same headspace. And by perverse incentive, much of what is produced and shown in contemporary art galleries seems calculated to fit within that narrow band of time and attention.

The two contemporary abstract painters, Carrie Moyer and Anke Weyer, now showing their work at David Klein Gallery until June 26, defy our ever-shortening attention span. Their smart, dense, idiosyncratic paintings ask–or require–that we pay attention.

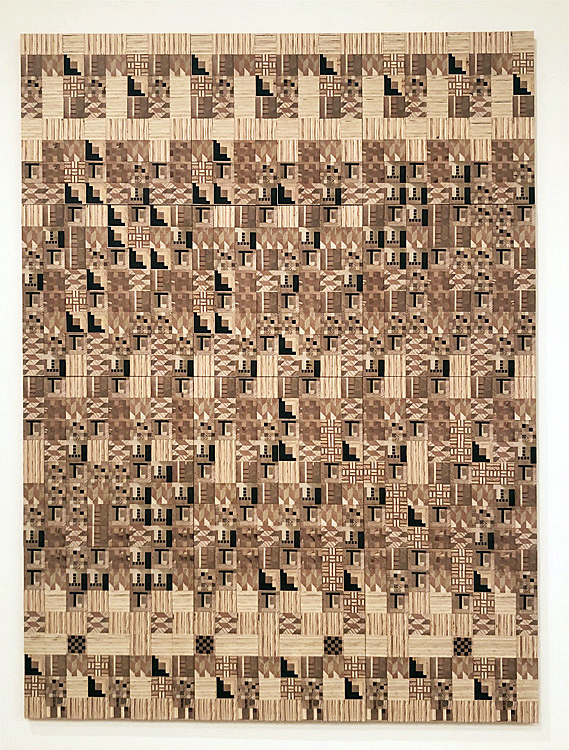

Carrie Moyer

Spider Song, Carrie Moyer, 2018, acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72” x 84” photo courtesy of D.C. Moore Gallery and David Klein Gallery

In a 2016 interview for Hyperallergic, Carrie Moyer recalls her midwestern childhood: “I was born in Detroit, where my family has longstanding roots. My grandfather was a policeman during the Detroit riots in the 1960s.” Moyer remembers visiting the Detroit institute of Arts with her mother, where she saw Diego Rivera’s murals. After a serious car accident during her first year of college in Bennington, Vermont, she moved to New York where she studied painting at Pratt Institute. After art school, Moyer found work as a freelance graphic artist, and in 1991 used her graphic expertise to create, in partnership with photographer Sue Schaffner, one of the earliest feminist public art projects, Dyke Action Machine! After graduate school at Bard, she turned to abstract painting, though her graphic art experience continued to influence her work.

Conflagration with Bangs, Carrie Moyer, 2015, acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72” x 84” photo courtesy of D.C. Moore Gallery and David Klein Gallery

Moyers’ picture-making incorporates methods employed by earlier abstract artists: the wonky referentiality of Elizabeth Murray, the diaphanous chromatic veils of Helen Frankenthaler, the cosmic frontality of Kenneth Noland. From these disparate–and one might say contradictory–elements, she synthesizes a formal vocabulary appropriate to the internet age. Her paintings refer to methods particular to traditions of abstract expressionism, while addressing the contemporary culture of the internet, the ubiquity of screens and video games.

For Moyer, the conceptual and formal originality in a work of art is its most important quality. Each painting is grounded in art history but adds to it the images and qualities that make us see and think about the world now in new ways. Of her work she says: ”I like to have illusionistic space and flatness in the same painting. Somehow this goes back to working as a designer in the advent of the desktop computer… I’m not so interested in a virtuosic brush mark, I’m more interested in setting up this relationship between atmospheric color and these hard-edge flat shapes.”

The Green Lantern, Carrie Moyer, 2015, acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72” x 60” photo courtesy of D.C. Moore Gallery and David Klein Gallery

Moyer’s canvases tend to the monumental and suggest mysterious, fugitive spaces between the real and the virtual. The three large paintings installed now in the gallery invite the viewer to fall into an alien world. Spider Swag nicely illustrates the artist’s strategy, which juxtaposes sharp-edged green and black icons painted with matte Flashe floating on the surface of the picture plane, in front of hazy, translucent washes of acrylic color–and occasional glitter–deeper within the pictorial space. The just-barely-referential eight-legged figure on the right skitters up the side of the painting, defying the implied gravity of the magenta-skied world.

The light comic edge of Spider Swag is characteristic of Conflagration with Bangs as well. A curvy red shape undulates behind a chartreuse proscenium–if a painting can dance, that’s what this one does. And in The Green Lantern, Moyer once again sets up a portal through which we can see a mysterious, incandescent figure.

In a 2016 Interview, Moyer describes the improvisational nature of her creative process:

I feel like if I am too formulaic about it, then I lose interest. If I can imagine the painting before I paint it, it’s not going to be an interesting painting. I need to figure it out as I am making it and be surprised by it. It would become too illustrative to me, because I am making these material discoveries every time I am making a painting. Things I didn’t know the paint can do. That requires having a lot of room for surprises and moments where I am not sure what is going to happen.

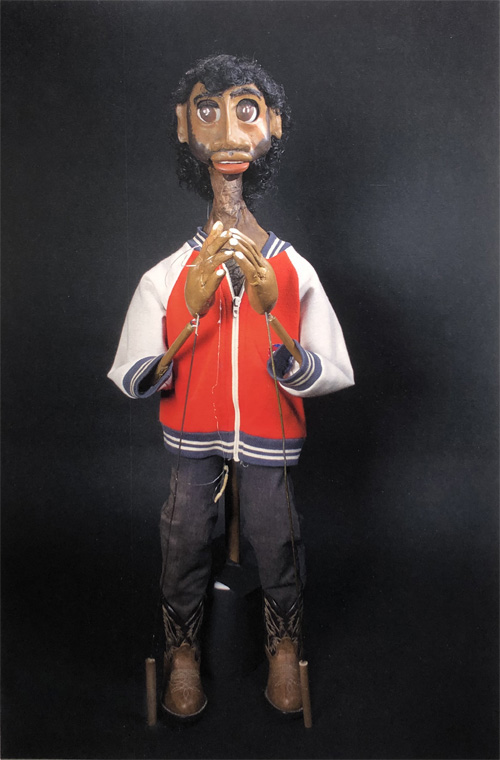

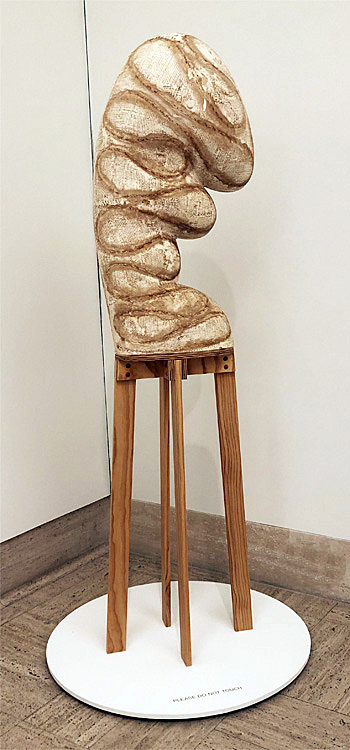

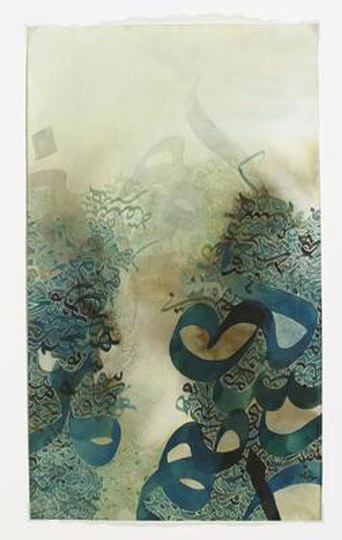

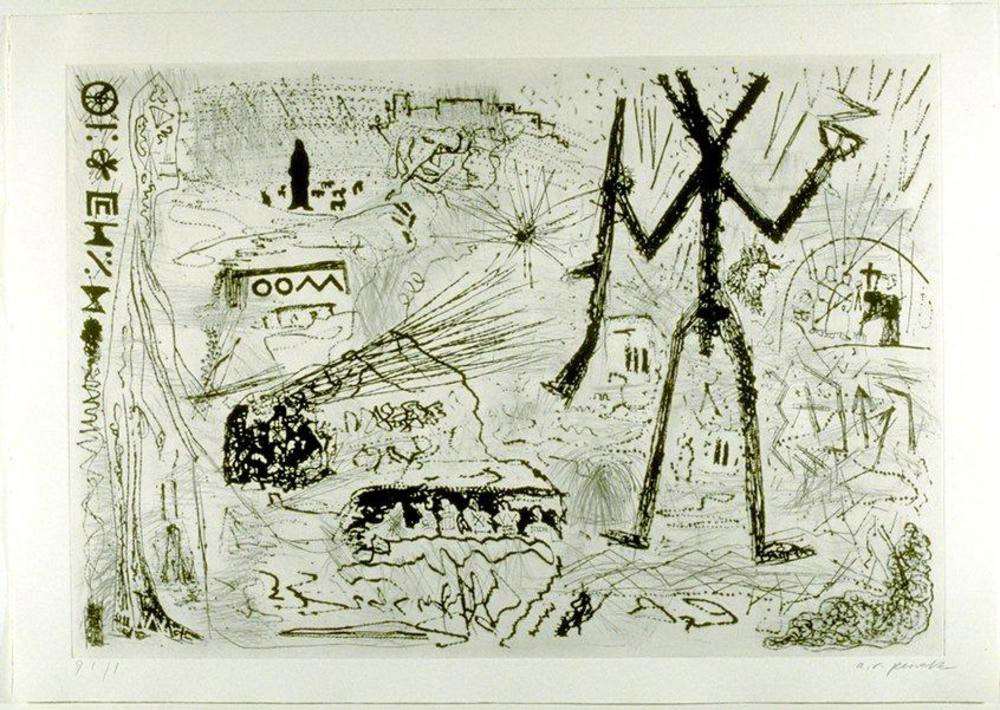

Anke Weyer

Still I’m Blue, Anke Weyer, 2021, oil and acrylic on canvas, 58.5” x 74.25” photo courtesy of Canada New York and David Klein Gallery

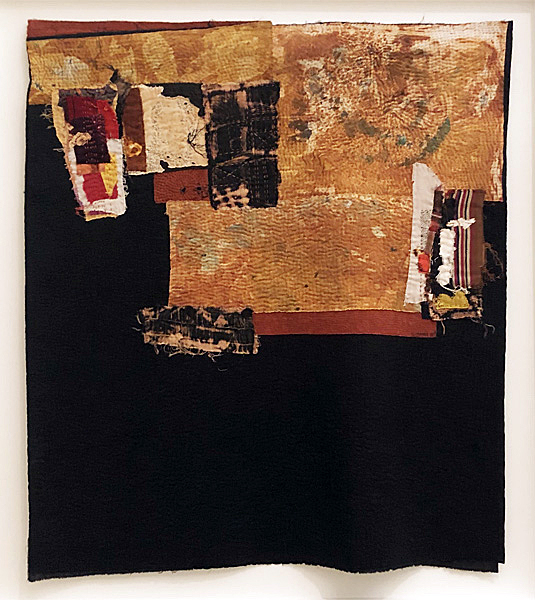

Although Anke Weyer makes use of some of the same art historical antecedents and improvisational techniques as Carrie Moyer, her paintings project a distinctly different mood–energetic, inventive, a little angsty. The New York-based, German painter has describedpainting as a form of “constant crisis management.” In a recent interview she adds “I can’t stand it when a painting looks as if it’s just a pastime. It is serious work and comes loaded with so much history and responsibility, which is what makes it so interesting.”

She considers her paintings to be a record of the creative process within the artwork: an intuitive series of marks and shapes that describe the visual and emotional content of her conversation with the painting. Each artwork is the record of a dialog that the painter engages with on the canvas. It is an inherently hermetic process. “Of course I cannot explain all my choices; most of them are made while painting, and there is no explanation for them other than the painting itself.”

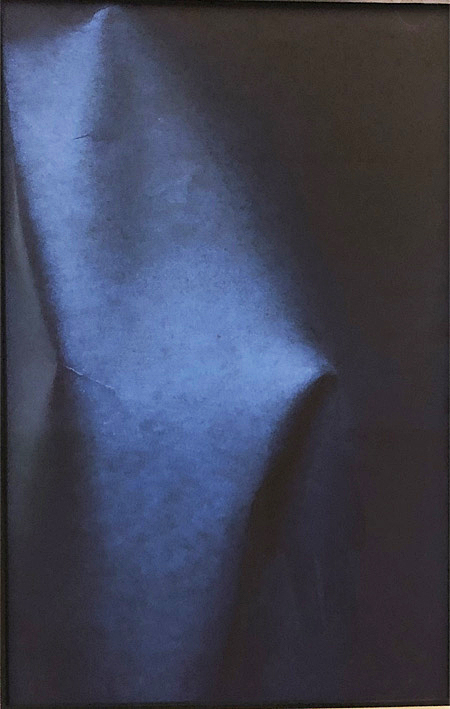

Invocation, Anke Weyer, 2021, oil and acrylic on canvas, 81.5” x 60.25” photo courtesy of Canada New York and David Klein Gallery

Her painting Still I’m Blue, illustrates some of the hallmarks of her art practice. The substance of the paint applied to the canvas leaves little room for illusionistic space. Exuberant strokes and shapes in vibrant colors circle the canvas in a vortex of chromatic energy. Weyer acts upon the painting as if it is a body upon which she adds layer upon layer of mark and gesture. In Invocation, the painter’s brush moves restlessly around the perimeter of the canvas leaving dark blue dots; an ominous, snaky red line slithers up the right side of the painting and the anxious yellow center is punctuated by restless white streaks. Each of Weyer’s paintings documents her perilous creative travels. She is a painterly Icarus occupying the risky space between falling and flying.

While Weyer does not claim to be continuing the tradition of Abstract Expressionism, she is cognizant of the historical underpinnings of her work. She describes her art-making practice as one of constant, highly instinctive editing, a slow process requiring time and contemplation. Like personal notes, all thoughts or traces of thoughts are allowed to play out on the canvas.

What is fascinating about both these painters, and what gives them a kind of constantly regenerative liveliness is the reflective mental consideration they require from the viewer. We must parse, meditate–marvel–at the infinite number of decisions they continuously make on the road to a finished work. We want, and get, from these painters a kind of freshness built upon the foundations of modern art history, but speaking specifically and genuinely to our moment.

Carrie Moyer and Anke Weyer, artists work at David Klein Gallery until June 26, 2021