The University of Michigan Museum of Art presents the work of Cullen Washington Jr. – The Public Square in the A. Alfred Taubman Gallery

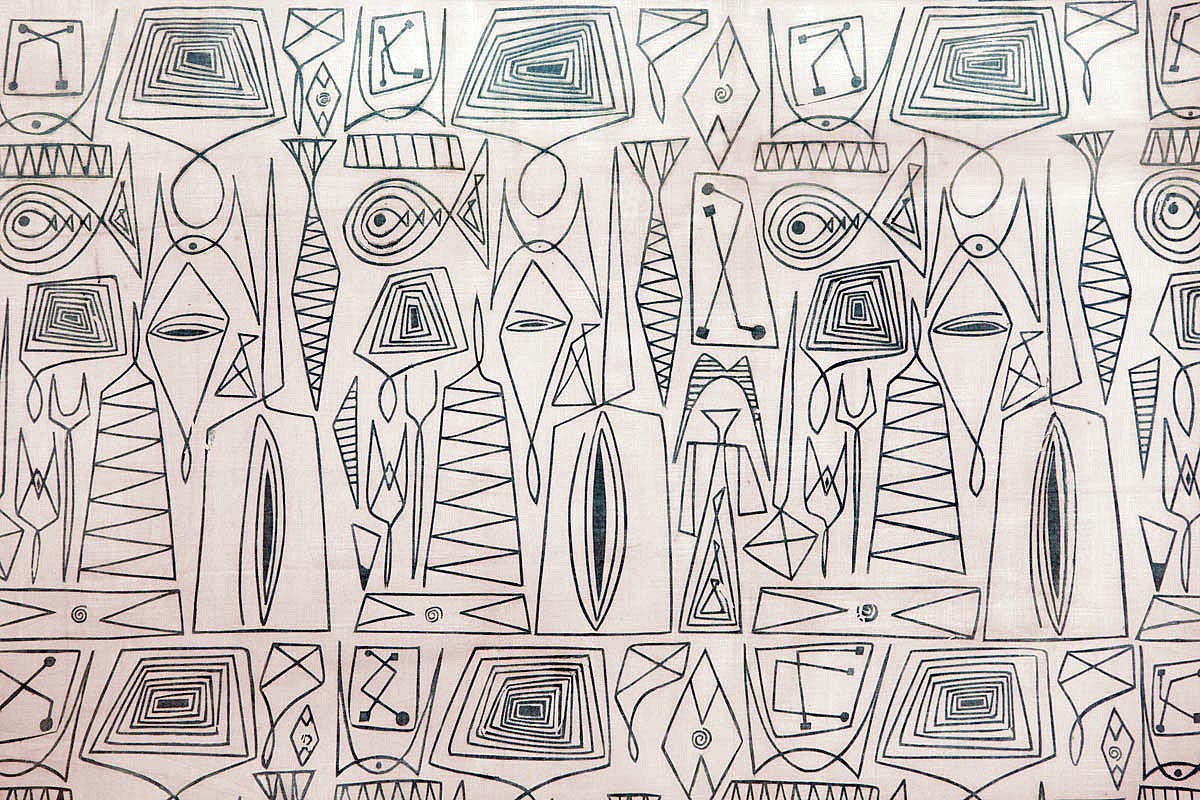

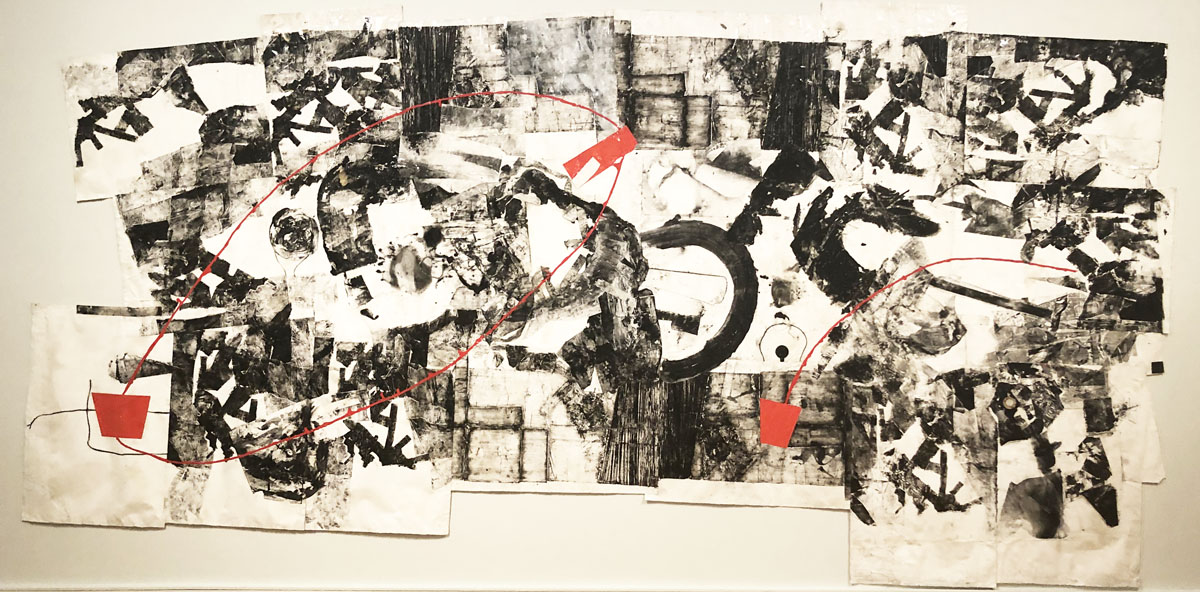

Cullen Washington Jr. – Agora 2, mixed media collage on canvas, 120 x 240″, 2018 , All images by K.A. Letts

Most of us don’t have the leisure time or the disposable income to travel to New York City this winter to immerse ourselves in New York Art Week, that atomized, commodified art mart where cash is king, and hype is the rule. But there’s an attractive local alternative at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where artist Cullen Washington proposes his vision for the museum as public square, a non-hierarchical, inclusive locus for discussion, interaction and cultural exchange in a respectful setting.

Washington hangs the premise for his solo show The Public Square upon his recent trip as a visiting artist to Greece, where he walked the space of the classical agora and considered it as a marketplace of ideas that might be adapted for a modern setting. His installation in the A. Alfred Taubman Gallery recapitulates the ground plan of an ancient city center. Five monolithic black walls mark the perimeter of the main installation. An open space in the middle of the gallery forms the exhibition’s heart, where the artist’s monumental collages dominate and activate the space.

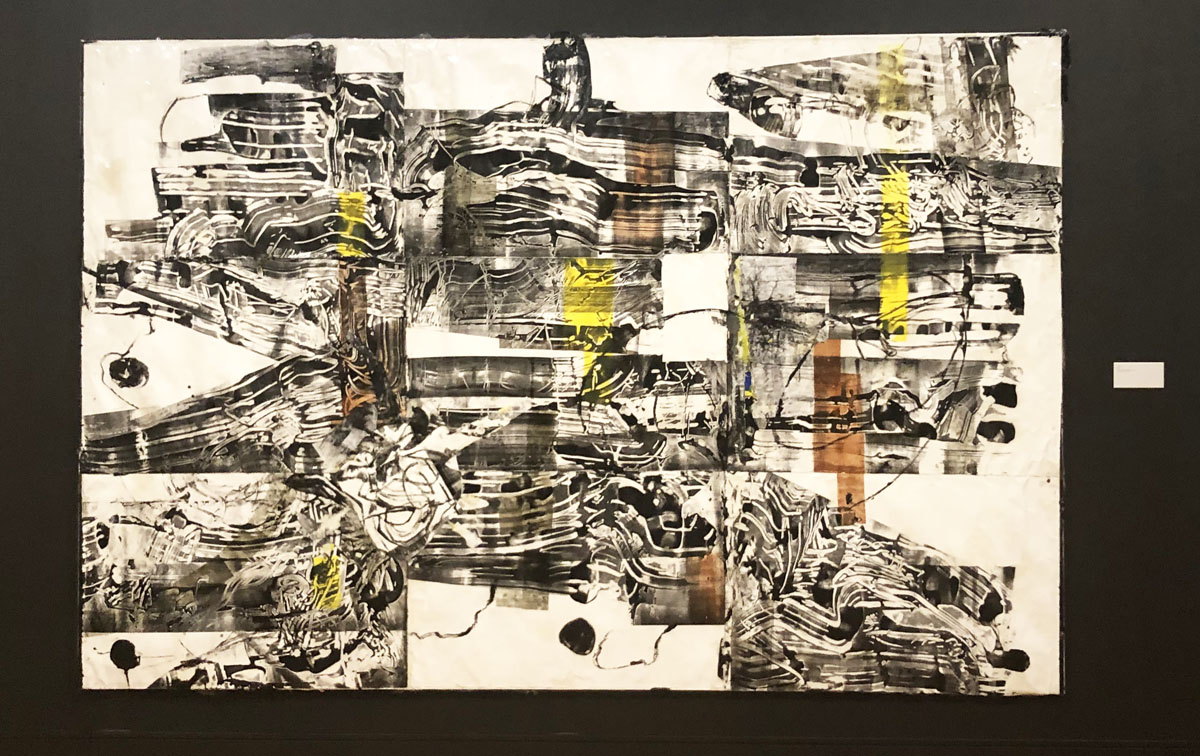

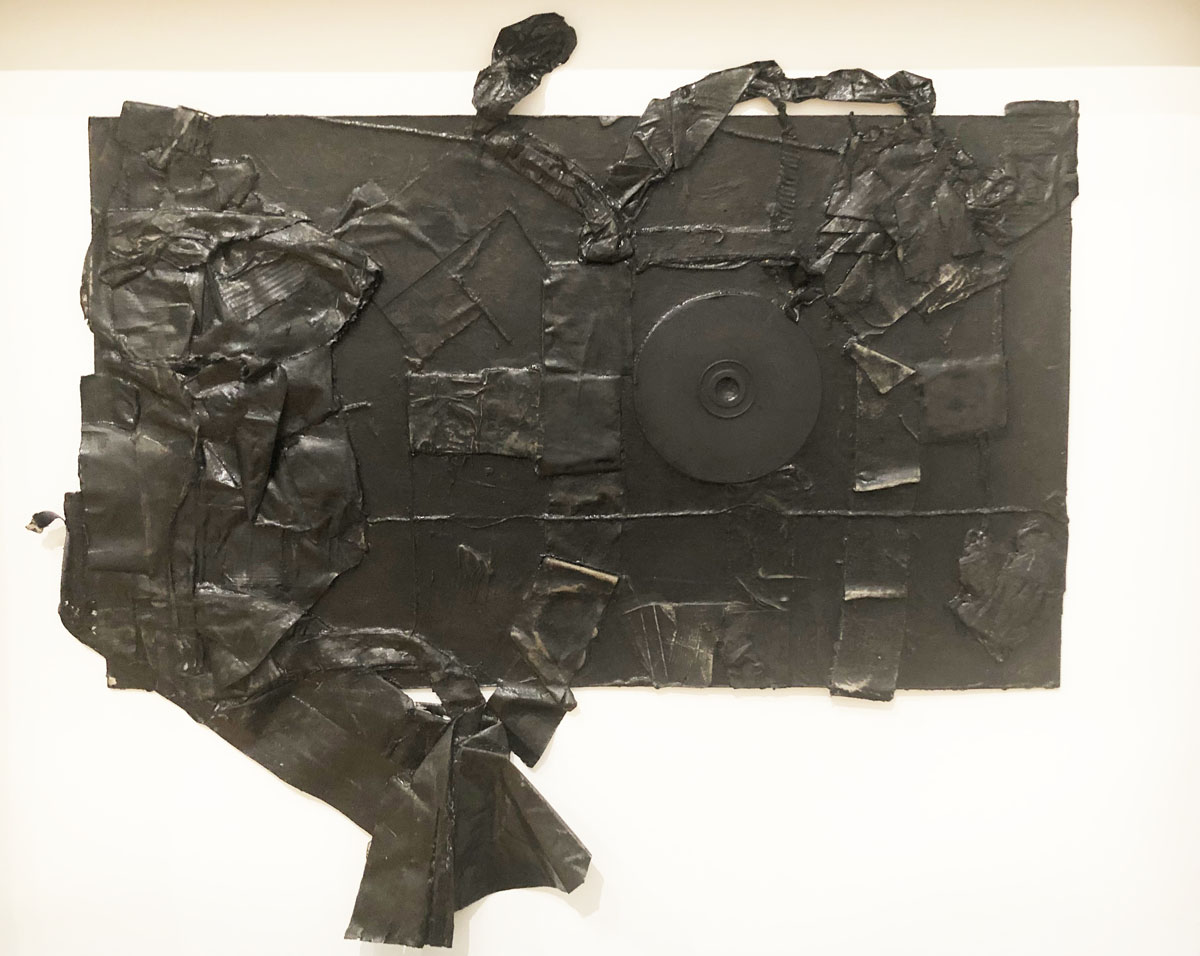

Cullen Washington Jr. – Agora 6, mixed media collage on canvas, 165″ x 96, 2018

Washington’s art practice can be described as gestural abstraction, a formal approach to art that some museum visitors might find intimidating. But a short and engaging video of the artist talking about his work, on a nearby gallery wall, provides a welcome map into his mind and his methods. Washington is an entertaining and approachable guide; his taped conversation with two studio visitors is down-to-earth and jargon free. His ongoing enthusiasm for the process of discovery in his work is palpable. “I’ve learned this [visual] language and I feel I’ve just started to write poetry,” he explains. He devotes considerable energy to describing his idiosyncratic process, which he characterizes as finding a place for his work in the gap between drawing, painting and printmaking. It’s an egalitarian space where notions about hierarchies in modes of expression as art or craft are rendered nonsensical. Washington insistently expresses his mission as one of flattening elitist distinctions in art, and in social class and race.

Washington’s giant collages are more built than painted. The artist attaches sheets of paper end-to-end defining outer perimeters. He then adds layers of marks, tapes, cut paper and the like to form compositions that roughly approximate the architectural grid and describe the floor plan of his imagined agora. Brushy marks that appear to be applied to the paper directly often turn out to be painted strokes from other pieces of paper that have been meticulously cut out and applied. In fact, many of the features on the surface are discreet blobs of paint, tape, plastic and paper that have been physically attached to the substrate. The effect is one of painterly abstraction, but the process is a bit more like writing: that is, he selects individual components and adds them together to create meaning. Washington uses color sparingly in marks and shapes that indicate compositional direction or that stand in for humanity moving within the built environment.

Cullen Washington Jr. – Agora 1, mixed media collage on canvas, 79″ x 171″, 2017

All the work in the central installation is compelling, but a couple of them are especially noteworthy. The squarish Agora 3 is exemplative of Washington’s methods; he clearly maps out the central space with black striated blocks loosely referencing the columns of the buildings surrounding the agora. Within that environment, lively movement abounds, punctuated by applied tape in red, yellow and green. The mood of the piece is lively and the agora is imagined as a venue for serious but playful dialog. Agora 6 is more monumental in effect, and the central void of the agora has almost disappeared. Intimations of the figure give this artwork a unique presence, and Washington’s restrained use of color is especially deft.

Cullen Washington Jr. – Agora 3, mixed media collage on canvas, 120 x 94, 2018

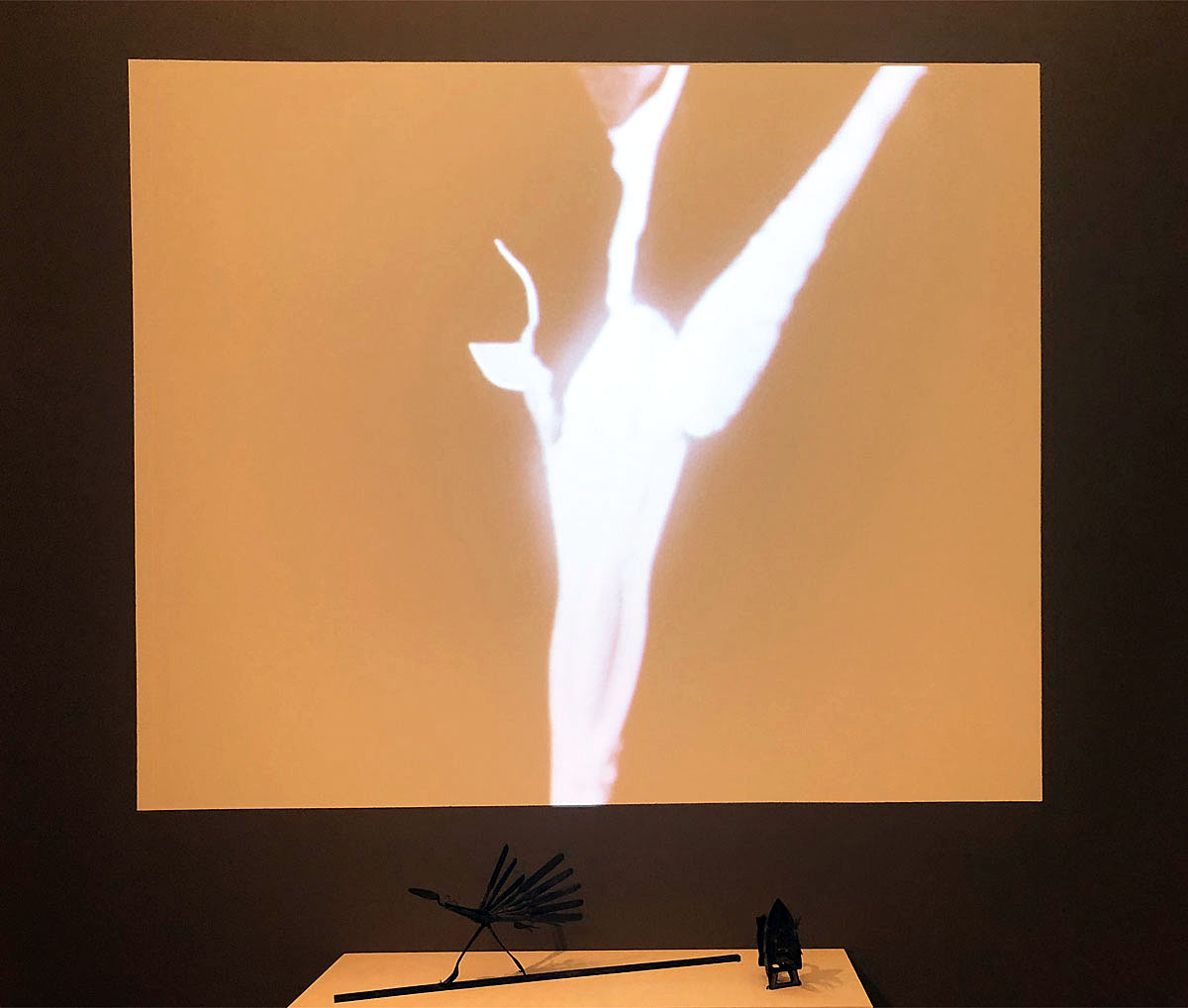

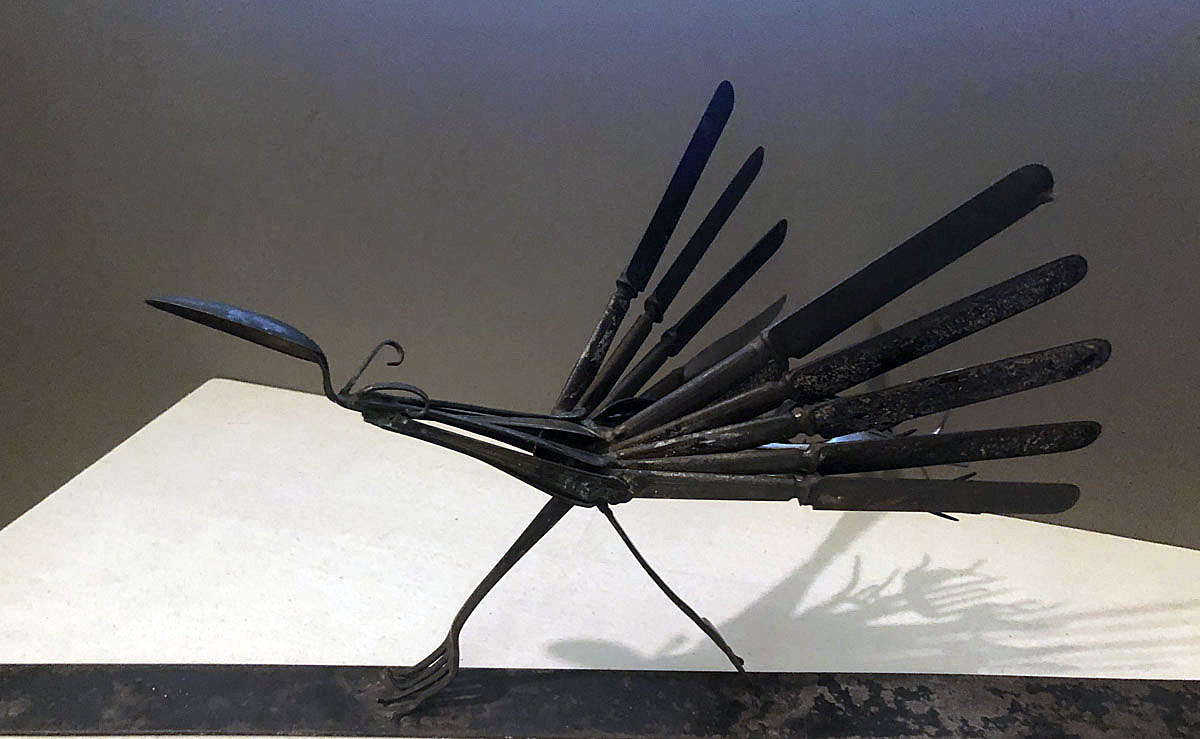

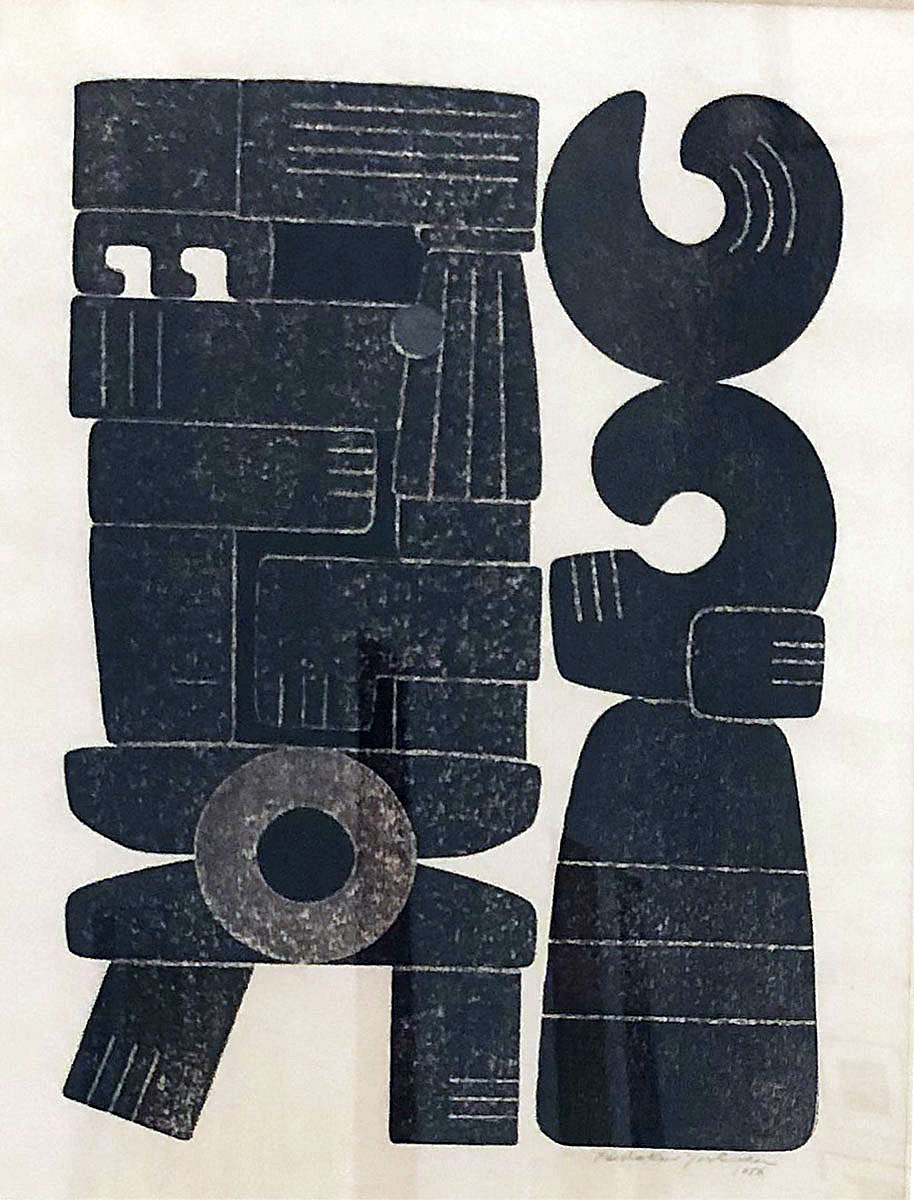

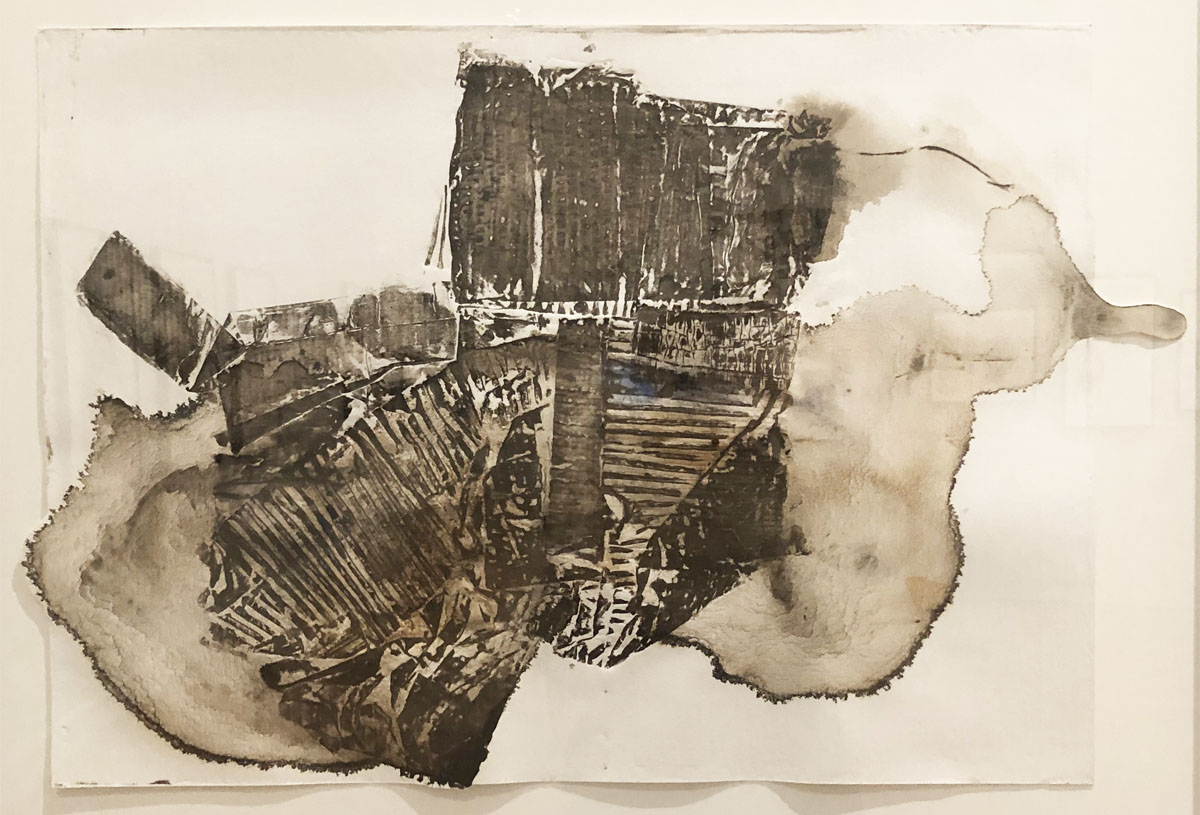

Smaller works in the side galleries make use of collagraph, a primitive type of relief printing, and other graphic techniques. During his summer residency in Greece, Washington took special note of the cardboard that came and went in the center of Athens. Inspired, he employed cardboard in these hybrid collages as well as other urban detritus to create relief monoprints that imply the fossil record of a vanished city.

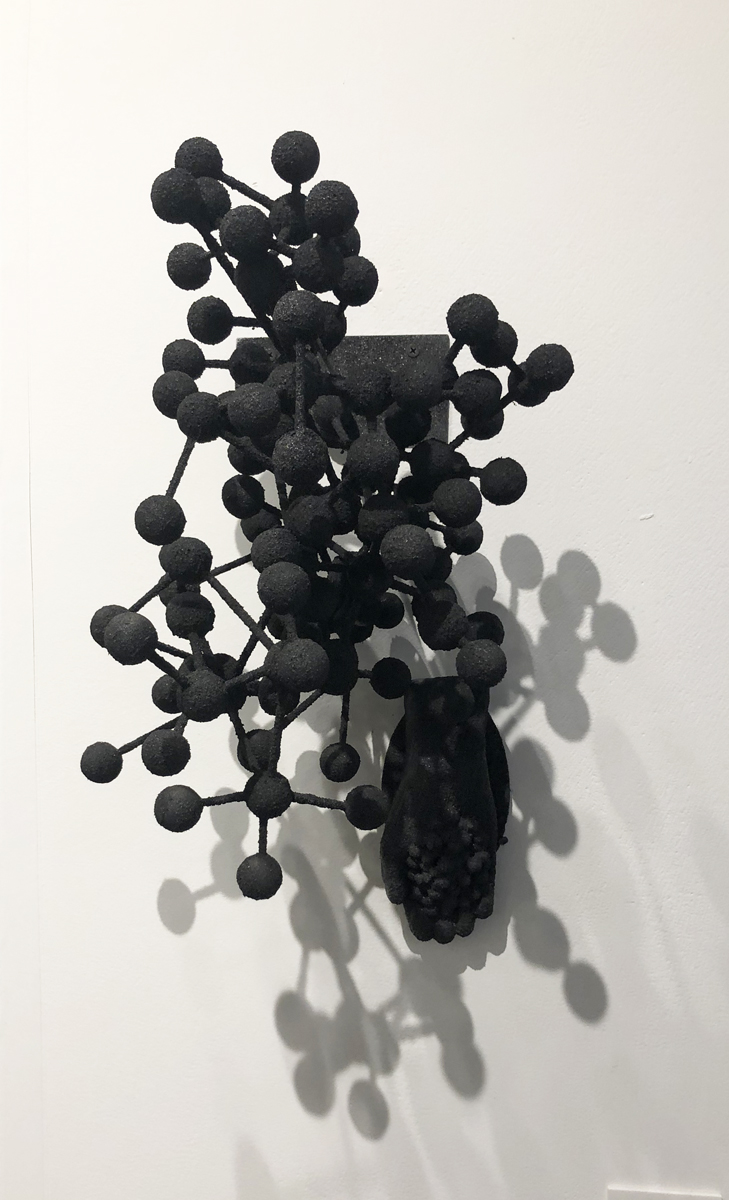

Cullen Washington Jr. – Od Matter S5 Original, mixed media on board, 235″ x 25″, 2016

Cullen Washington’s meditation on the importance of the public square as a setting for cultural and spiritual exchange reminds us that museums are, in themselves, modern agoras. Ideas, old and new, exist in the ‘now’ of a living culture there. They compete and debate there. They provide a context for understanding the past and present and might -just possibly, in this polarized age –propose a way to the artist’s dreamed-of future of understanding and hope.

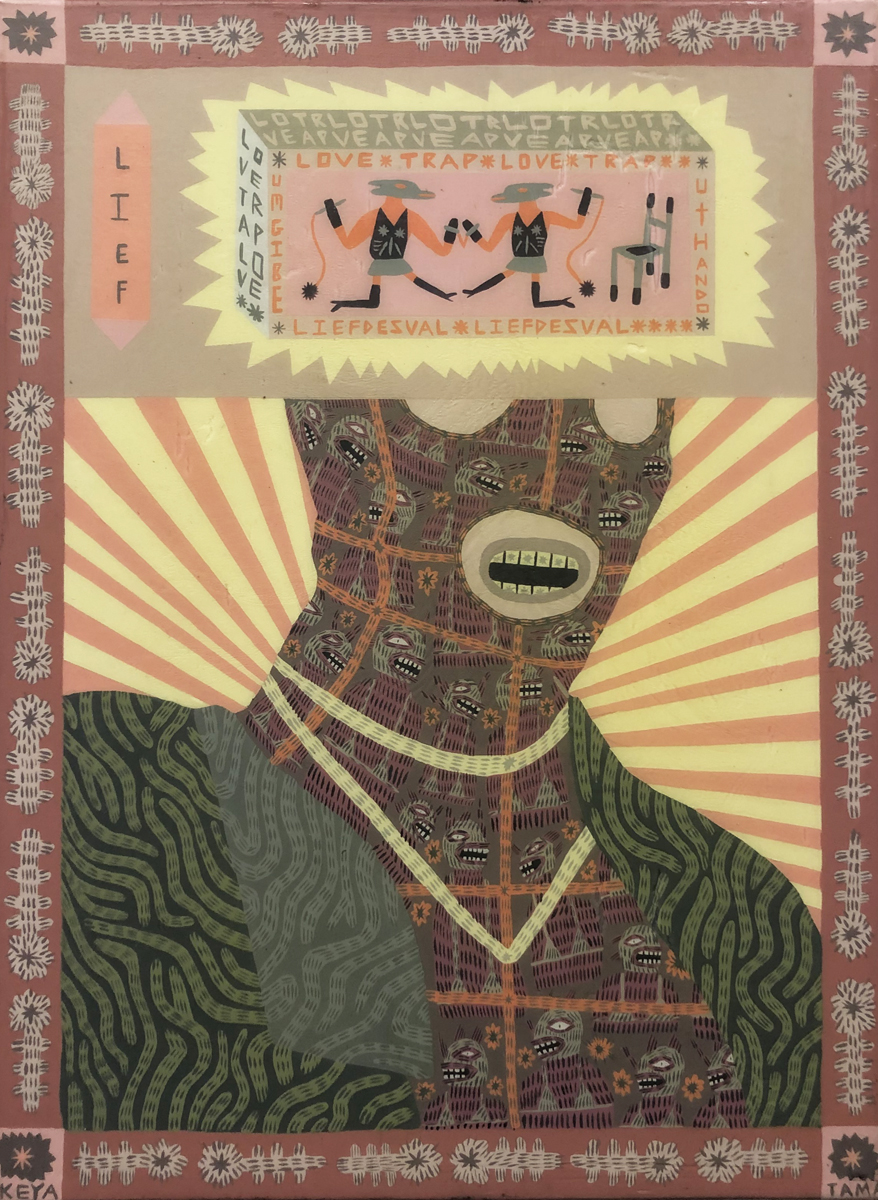

Cullen Washington Jr. – Aegina 4, etching ink on paper, 18 x 30″ 2019

The Public Square at UMMA is on view until May 17, 2020