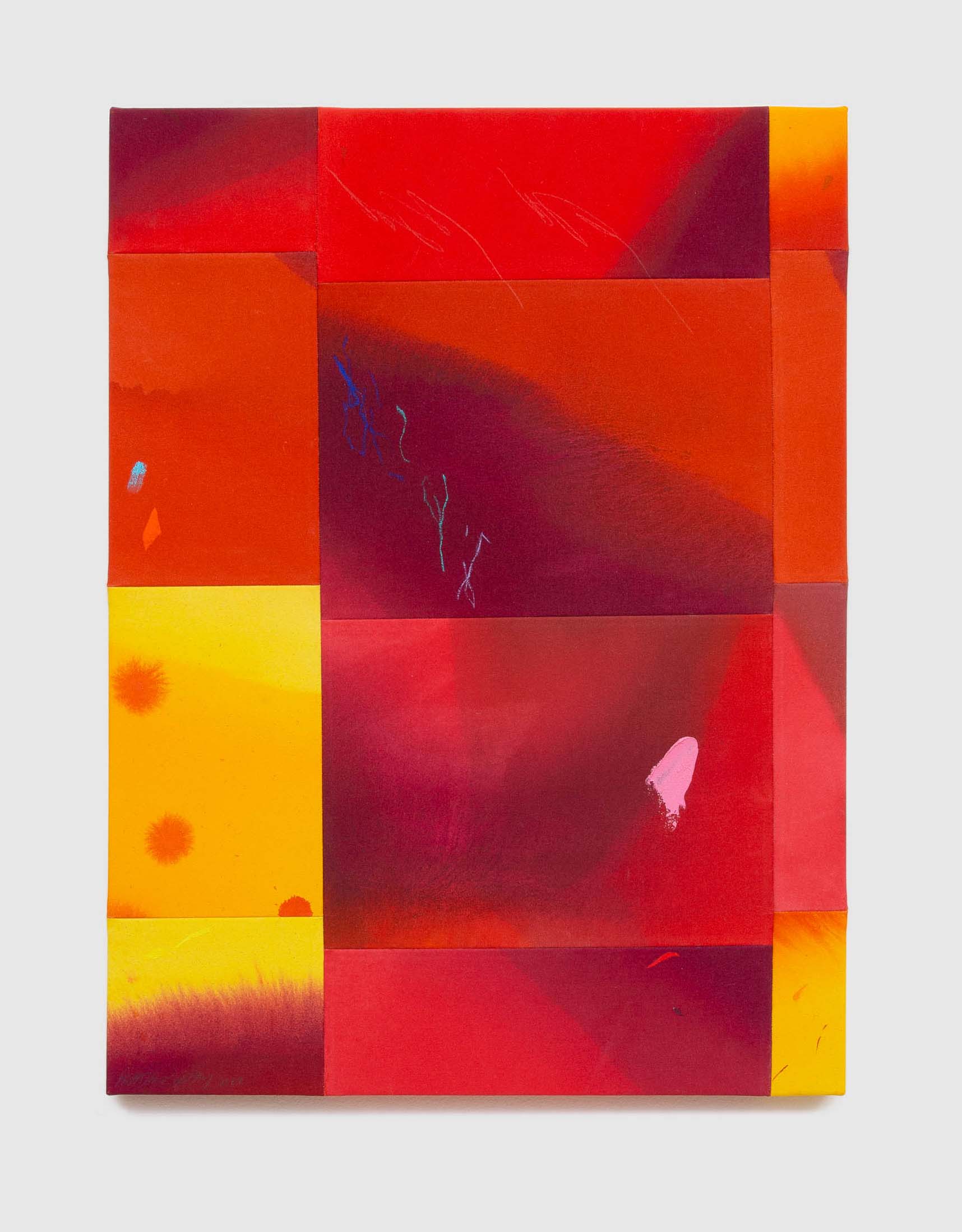

Installation shot of Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, which will be at the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum in University Center north of Saginaw through Dec. 10. Courtesy Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum.

In contemplating the after-effects associated with mining uranium and testing the resulting nuclear devices, Geoffe Haney probably speaks for all of us when he admits he had no idea what a large operation it all is, even today.

“When I thought about atomic testing,” said Haney, collections manager at the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum north of Saginaw, “I thought about the Marshall Islands or Nevada. I thought, ‘OK, we learned our lesson, and everything worked out.’ But,” he added, “it’s all ongoing, and the amount of uranium mining is insane.”

A traveling show at the museum on the Saginaw Valley State University campus, Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, underlines the wide range of countries that still have working mines. (The trade association for the nuclear industry, the World Nuclear Association, reports active mining in 20 countries.) The exhibition also points to the uncomfortable fact that most of the mines seem to be on the land of, or adjacent to, indigenous communities, whether in New Mexico, South Australia, Arizona, Saskatchewan or Hawaii – all of which contributed works for this colorful, ultimately disturbing show.

Exposure will be up through Dec. 10, 2022.

Organized by the IAIA Contemporary Museum of Native Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the exhibition – which heads to Los Angeles next – is both engaging and politically astute.

For example, a text panel instructs us there are over 500 abandoned uranium mines and mills on Navajo Nation and Pueblo lands, “and most of them are unmarked.” Until 60 years ago, Native American miners worked in the uranium mines “without any protective equipment and lived in houses constructed from contaminated material.” Many were claimed by uranium-related illnesses and unknowingly seeded birth defects and cancer that have spread through succeeding generations.

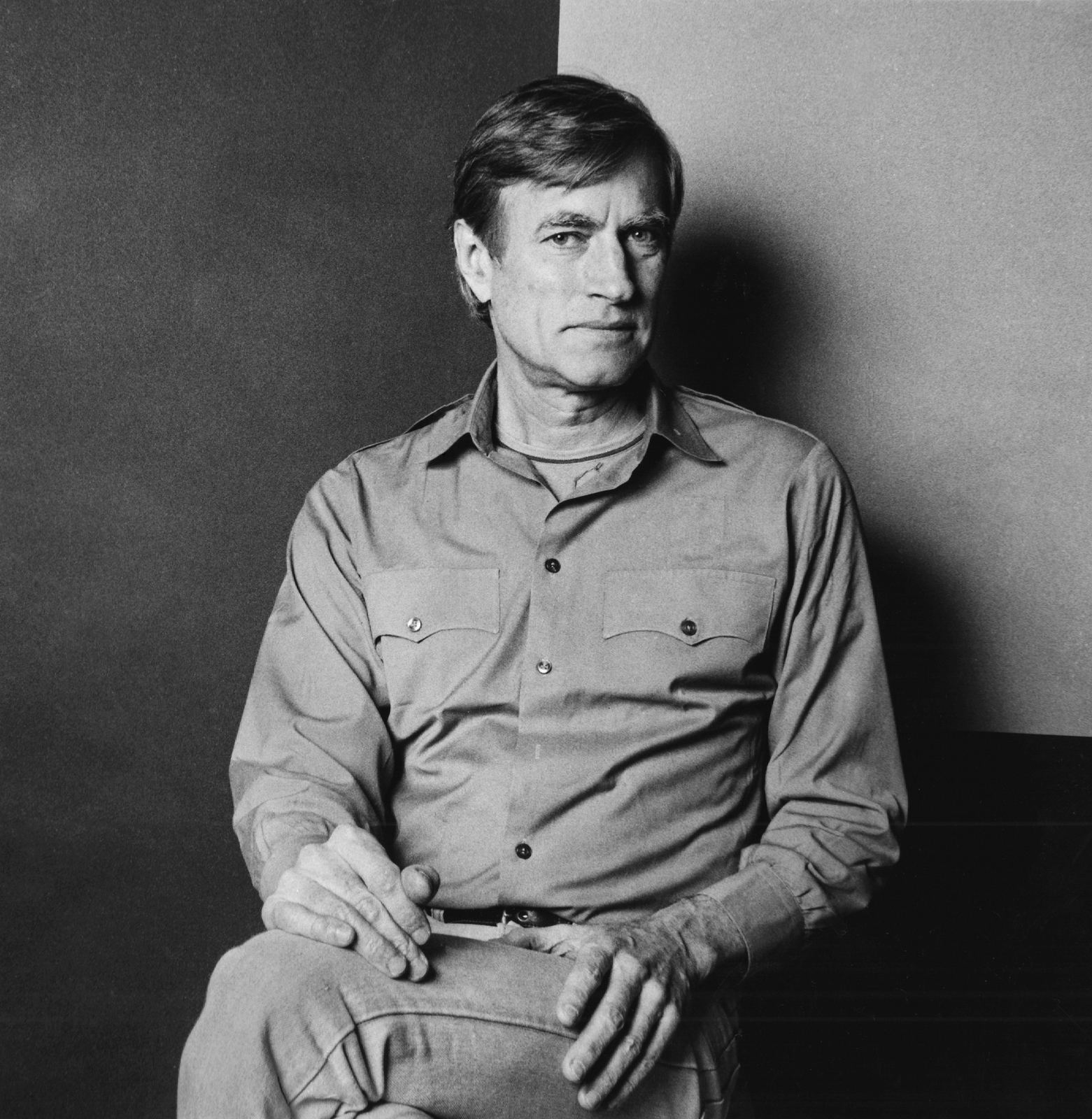

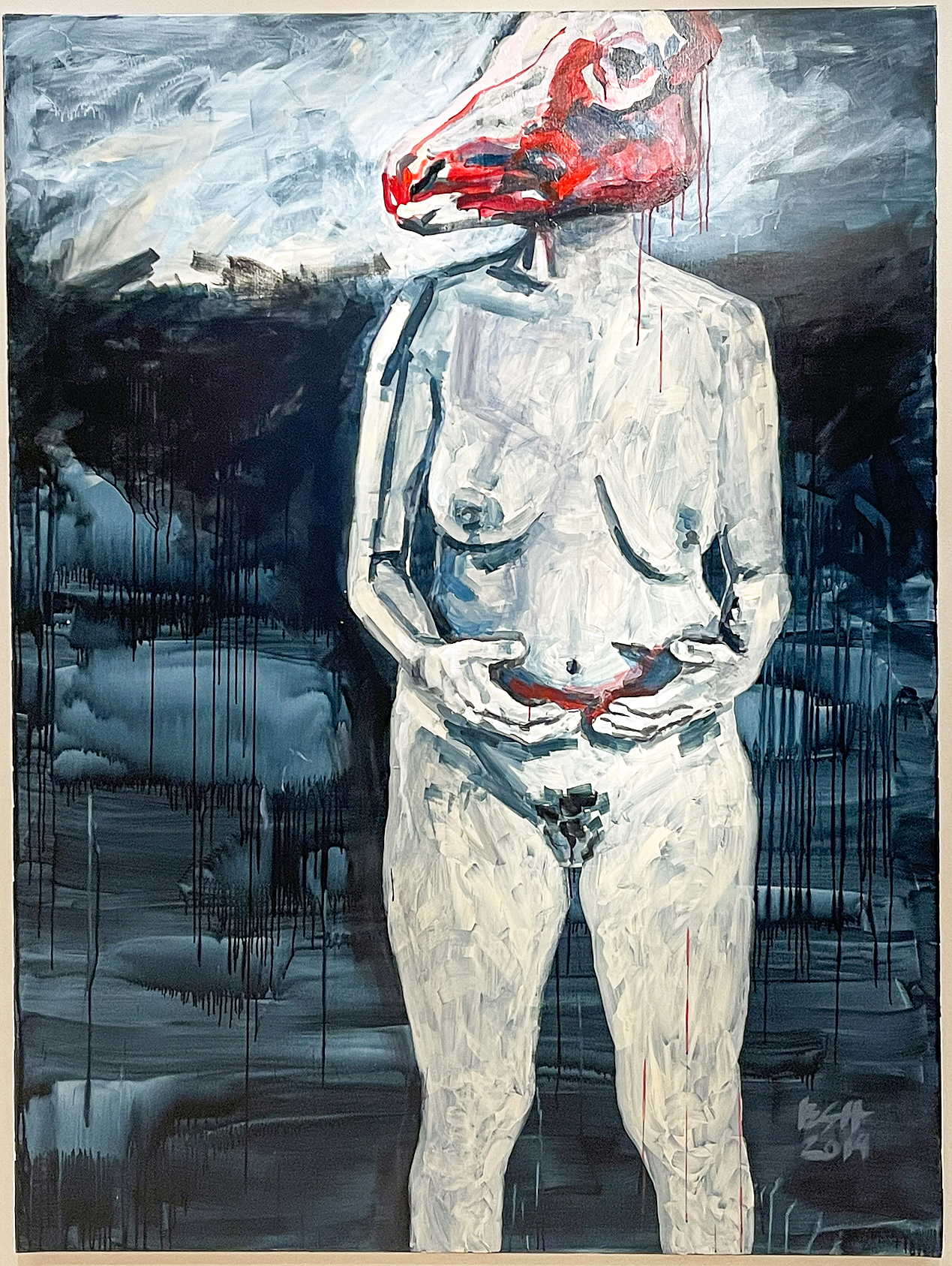

Bolatta Silis Høegh, Outside (from the Lights On, Lights Off series), 2015.

This suggestion of genetic tragedy gets a nice treatment by the Greenlandic Inuit artist, Bolatta Silis Høegh, who now practices in Copenhagen. Outside, a self-portrait from her 2015 “Lights On, Lights Off” series, presents a naked figure, rendered in crude, choppy, gray strokes. The woman is surrounded by a black landscape both lurid and elegant, and where her head ought to be there sits instead a bloody cow’s skull, gazing off to the right, as if it’d just heard something.

Is this a mask? Hard to tell, but it somehow doesn’t feel likely. All in all, Høegh conjures up a powerfully despairing portrait with an edge of anger.

Visually amusing but no less hopeless in its way is Adrian Stimson’s Fuse 3 from 2010. The member of the Canadian Blackfoot nation gives us a beige, beach-like desert landscape under a heavy gray and black sky. At the left horizon, a diminutive mushroom cloud comprised of black, salmon-pink and dark yellow is rising into the sky, its blast apparently causing the mustard-colored bison who dominates the canvas to jump in alarm.

The treatment of objects and landscape alike is interesting. The mushroom cloud reads a bit like a cartoon, gaudy and almost cute, but the buffalo is rendered with sympathetic precision. And there’s surprising beauty and technique in both the menacing sky and milky-beige sand in the foreground.

Adrian Stimson, Fuse 3 (Series of three paintings), Oil and graphite on canvas, 2010. Courtesy Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Garden.

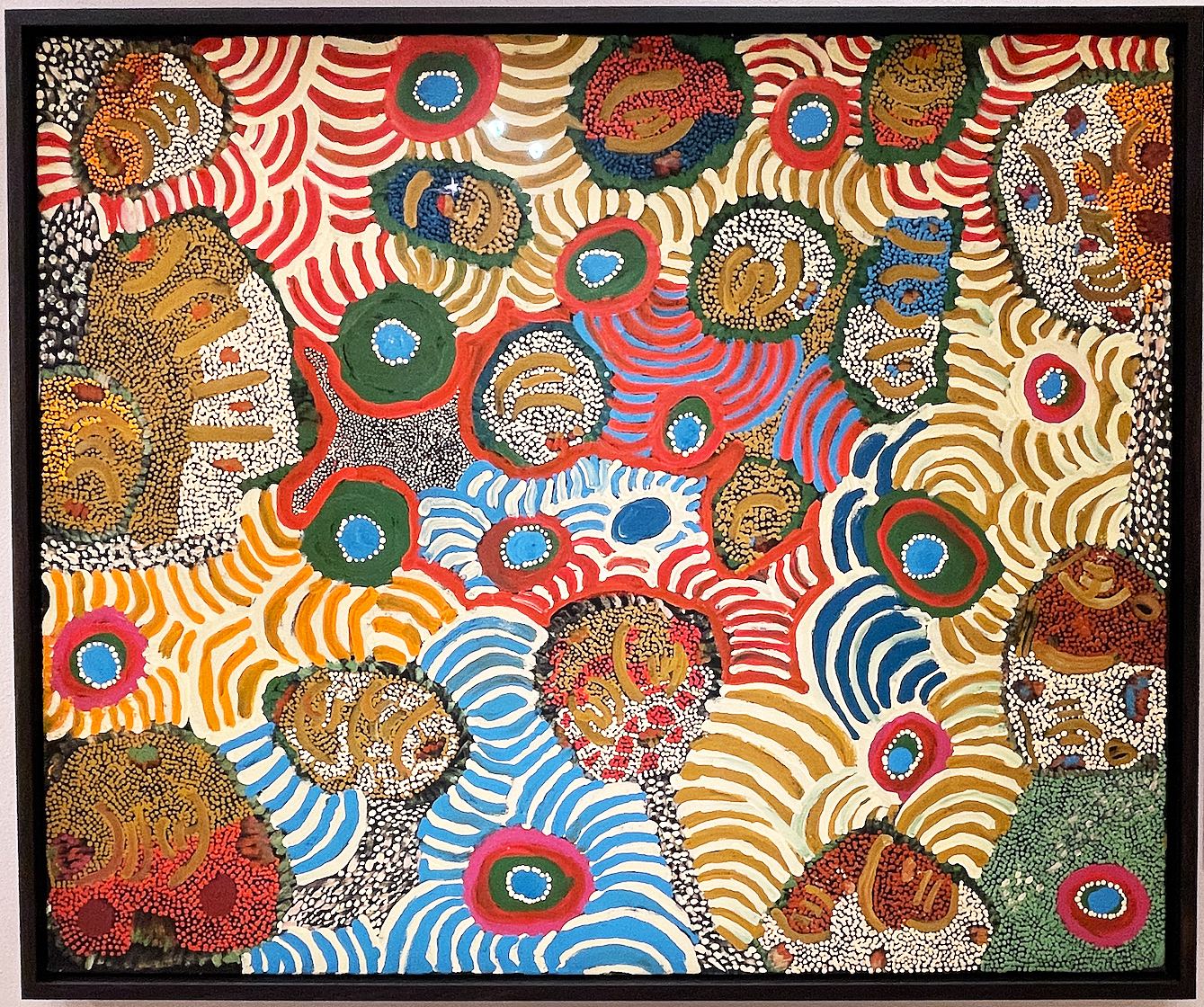

Between 1956 and 1963, the United Kingdom conducted seven nuclear tests at the Maralinga site in South Australia. At first blush, with its exuberant circles and parallel curves in a rainbow of colors, “Maralinga Bomb” looks almost playful. But Karrika Belle Davidson, an Aboriginal woman who was near one of those tests with her young son when it detonated, has embedded this acrylic abstract, so cheerful on the surface, with hard-to-decipher representations of the dead and dying, and the hundreds of spot fires that burned long after the explosion had mostly cleared.

Kunmanara (Karrika Belle) Davidson, Maralinga Bomb, Acrylic on canvas, 2016.

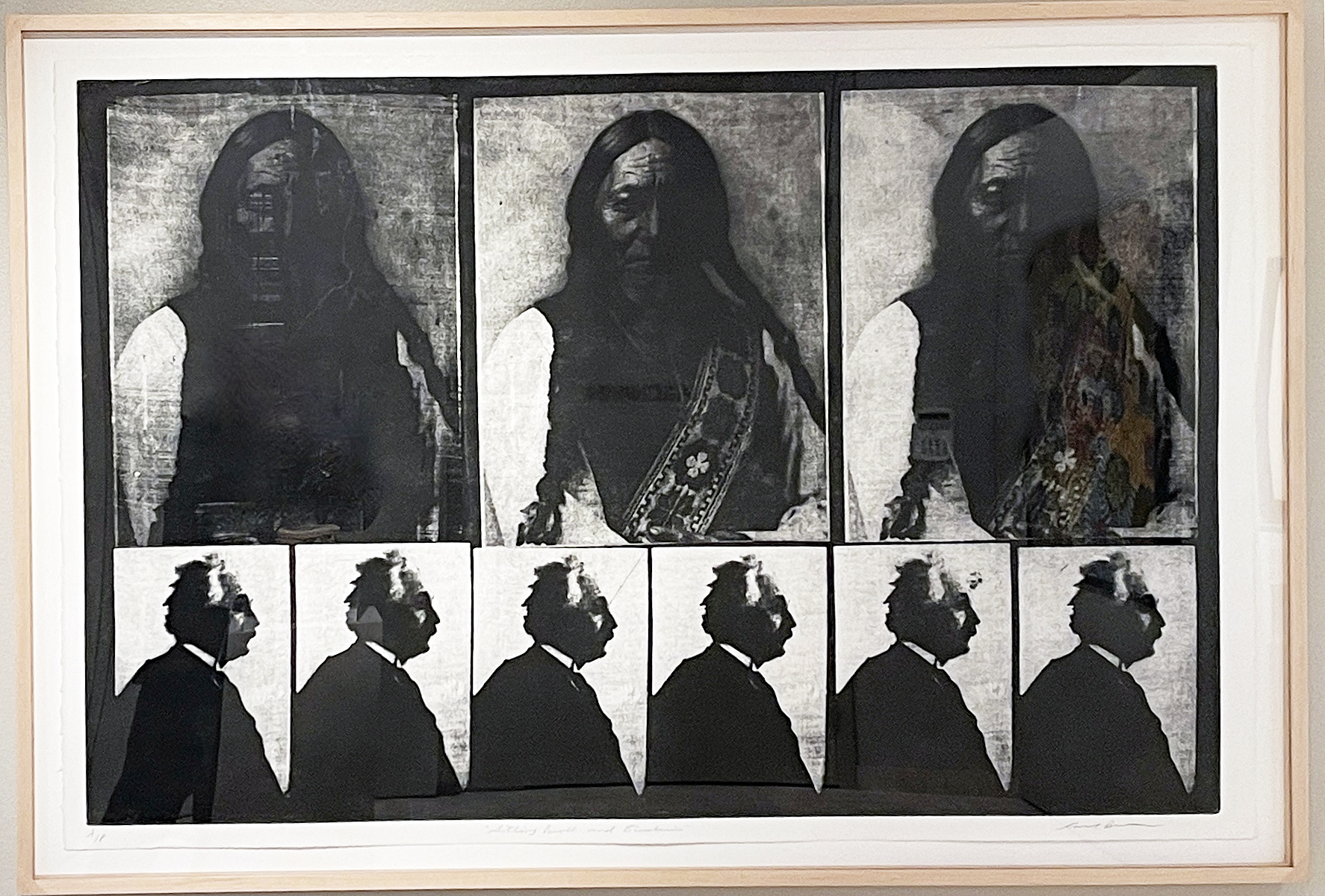

With Sitting Bull and Einstein, Ojibway printmaker and artist Carl Beam pairs the legendary Native leader with the scientist whose genius led to the most frightening destructiveness man has ever wielded. Here the Saskatchewan native, who influenced an entire generation of First Nations artists before his 2005 death, lines up a half dozen lookalike pictures of Einstein in profile along the bottom of this black-ink etching, topped by three larger images of Sitting Bull. Calm and august, he looks straight out at the viewer. There’s a little playing with what academics might call the standard hierarchies of power here, with the world-acclaimed scientist overshadowed by the mythic Native American.

Carl Beam, Sitting Bull and Einstein (From the series The Columbus Suite), Etching in black ink on paper, ca. 1990. Courtesy Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Garden.

Some prospects – wholesale obliteration or lingering death, say — are too ghastly to dwell on without pause, which is doubtless why the art of catastrophe and doom often includes a side of black humor.

Greenlandic Inuit artist Ivinguak Stork Høegh invokes this cockeyed tradition with his funny, deeply odd, Sussa Manna Aserrungikkaluarutsigu (We Do Not Have to Destroy This Area), which stars an exploding mountaintop and, looming in the foreground, two dorky kids. Both taken from period photographs, one boy is wearing literal, rose-colored glasses. It’s only when you look close and get past the general jokiness that you realize the child’s face is twisted in a hideous grimace – as appropriate response to nuclear contamination and ruin as one can imagine.

Ivinguak Stork Høegh, Sussa Manna Aserrungikkaluarutsigu (We Do Not Have to Destroy This Area), Digital photograph, 2020. Courtesy Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Garden.

Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology will be at the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum at Saginaw Valley State University through Dec. 10, 2022.