Stop Making Sense at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago

“Surrealism: A Conjured Life” installation view All Images Courtesy of Sarah Rose Sharp

There is a fairly structured approach to cognitive development within our society—we try to make order of chaos. We assigned meanings to symbols (like letters or shapes), and organize those symbols in configurations that generate more complex meanings (like words or images), and continue along, stringing together ever-greater numbers of shapes and letters to make cogent arguments and beautiful imagery. We (hopefully) teach our young people fluency with the existing sets of shapes and letters, so they can grow up to understand all the meaning that has come before, and potentially contribute thoughts of their own to the collective understanding.

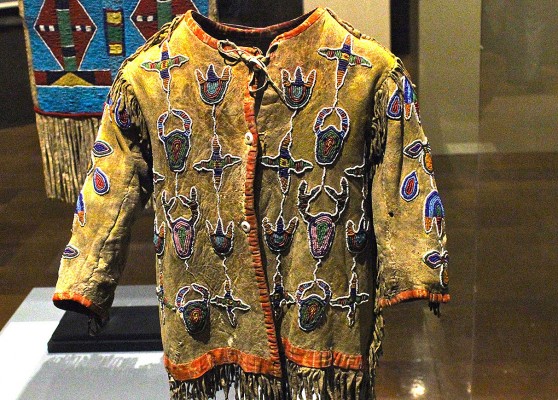

Unless we don’t. The Surrealist movement, which formally emerged in Paris in the mid-1920s, supplanted the basic order of established meaning, challenging straight-line association and favoring experimentation across a wide range of media, including theater, writing, film, poetry, and of course, visual art. A survey of foundational and second-generation Surrealist art from the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) collection provides a vivid showcase of some of the lesser-known founders of Surrealism and those that followed in their footsteps—including a number of Chicago-based contemporary artists—and underscores the difficulty inherent in making work that disrupts the basic building blocks of meaning, as they are instilled in most of us from a young age. The work on display includes sculpture, paintings, drawings, and multi-media installations, and a wild array of subjects, rife with texture and symbols. Paradoxically, the exhibition materials provided by MCA immediately attempt to contextualize and categorize some of the symbols, themes, and motifs commonly explored by Surrealists—including death, winged messengers, sleep and dreams, the grotesque, mannequins and dolls, and phantasmagoria—which to some degree undermines the destabilizing objectives of Surrealism as a movement. Again, being nonsensical, generating and/or accepting ambiguous meaning in art, is harder than it initially seems.

Harry Bertoia, Landscape Fantasy (n.d.), Lead, wire, and stone slab

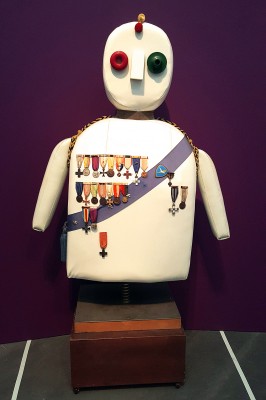

The gallery is organized into two spaces, an inner circle with rich purple walls that displays some of the movement’s foundational contributors, such as Max Ernst, René Magritte, Dorothea Tanning, Kay Sage, and Remedios Varo. There are some outstanding works here, each radically different from the next – the aesthetics of Surrealism are as disparate and personal as the individuals who worked within the movement. Landscape Fantasy (n.d.) by Harry Bertoia is a delicate collection of lead and wire constructions, resembling a flea circus-like playscape, on a stone slab. This minimal and understated work sits just adjacent to Punching General (1969) by Enrico Baj—an cartoonishly-shaped and upholstered military figure on a spring, designed, presumably, to act as a sparring partner for the expression of animosity toward the military state. Within a nearby patch of wall is a four-part installation by Doris Salcedo; Atrabiliarios (1993) encases shoes recovered from victims of mass violence in wall niches, stitching them in behind semi-opaque membranes that give them an otherworldly quality.

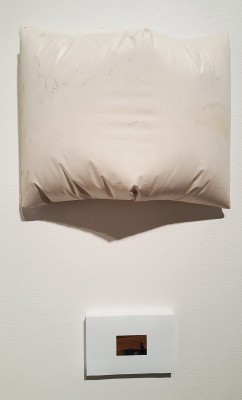

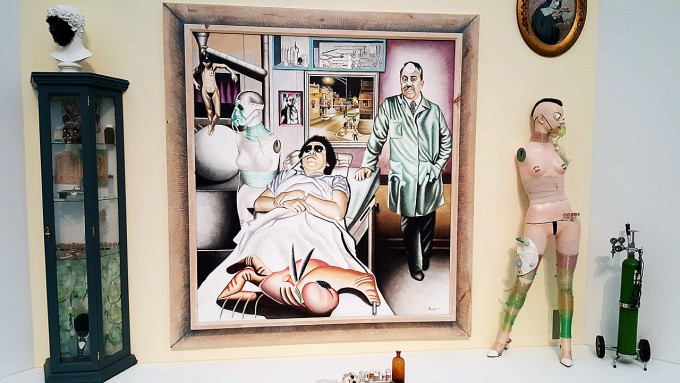

Marcos, Raya, Night Nurse (1993/96), Installation view

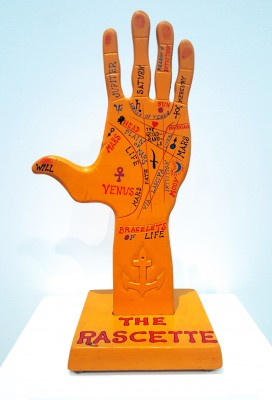

Things are no less esoteric and trippy in the outer ring, which highlights Chicago-based artists that were influenced by the Surrealist movement. An entire wall is devoted to Marcos Raya’s disturbing installation Night Nurse (1993/96), which feels as though one of Frida Kahlo’s medical forensic paintings jumped its frame to become a department store window display. Paintings on Plexiglass suggest internal organs, literally hidden levels of processing, and highly textured paintings pile on revelations in the opposite direction—Surrealists were seemingly obsessed with abstracted notions of the body’s inner workings. The Rascette (1961) by H.C. Westermann, attempts to highlight the secret information encoded in our very palms. A freestanding display presents a two-sided work by Henry Darger—Chicago’s much posthumously celebrated outsider artist, who spent his professional life as a hospital custodian, all the while working on an longform manuscript peppered with illustrations of kewpiesque children in various fantasy states, that is equally disturbing as it is inspired.

H.C. Westermann, The Rascette (1961), Painted woo

Enrico Baj, Punching General (1969), Vinyl, metal, cloth, ribbon, foam,

Many contemporary artists in various media have used transcendental meditation as a method for discovering new perspectives and inspiration, and some of them—for example, filmmaker David Lynch—create work that is among the most challenging, dislocating, and original, in a field dominated by sloppy exposition and audience hand-holding. “Surrealism: The Conjured Life” presents a critical mass of work that collectively instigates a kind of dream state—surrounded by so much disordered thought, the viewer cannot help but surrender, at least temporarily, and cease to impose logic upon what she sees.

For some, this may prove to be an extremely alienating experience, but for this reviewer, it is a welcome respite from the cultural spoon-feeding that is the hallmark of our media age, designed to sell consumer products, above all else. Any one of the works in the exhibition would be worthy of longer consideration, but the best effect of all is the collective disorientation. It is a very different kind of shock and awe than the political and media process used to handily to inspire fear and division among the populace; it is a confusion that inspires wondering, and with it, transcendence.

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois https://mcachicago.org/Home