An installation shot of Skilled Labor: Black Realism in Detroit at the Cranbrook Art Museum, which will be up through March 3, 2024. (At left is Patrick Quarm’s Three Transitions.) Running through March 3, 2024 as well is LeRoy Foster: Solo Show. All images Courtesy Cranbrook Art Museum.

Two new exhibitions at Cranbrook Art Museum showcase the considerable talents of Detroit’s African-American portrait painters, both past and present. Both LeRoy Foster: Solo Show, and Skilled Labor: Black Realism in Detroit will be up through March 3, 2024.

Skilled Labor is the larger of the two, and a complete stunner. The very first canvas you’ll see on entering this 20-painter group show is Mario Moore’s huge, undeniably sexy Thornton and Lucie Blackburn in Canaan – with a 21st-century Black couple in bathing suits lying on the Windsor waterfront at night, the Detroit skyline, part of it in flames, across the river.

Mario Moore, Thornton and Lucie Blackburn in Canaan, Oil on linen, 2022.

Chief curator Laura Mott organized this show with Moore, a 2018 Hodder Fellow at Princeton University, and she loves “how he conflates history and time into one canvas.” In this case Moore’s employed contemporary Detroiters to portray the Blackburns, a couple who fled Kentucky slavery in 1833, ultimately making their way to Canada via Detroit and the Underground Railroad.

A bit like Kehinde Wiley, who inserts young, tattooed and dreadlocked Black guys into historical paintings of war heroes on rearing horses (Wiley turned one of those into a sculpture that now sits on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia), Moore recontextualizes and illuminates history by dropping it into a modern framework.

Be sure not to miss Moore’s other large piece, A Student’s Dream, in which the artist himself, staring straight out at the viewer, lies naked on a dissection table surrounded by white doctors – a reference both to Moore’s own brain surgery, and the medical profession’s callous use of Black bodies in decades past for scientific research.

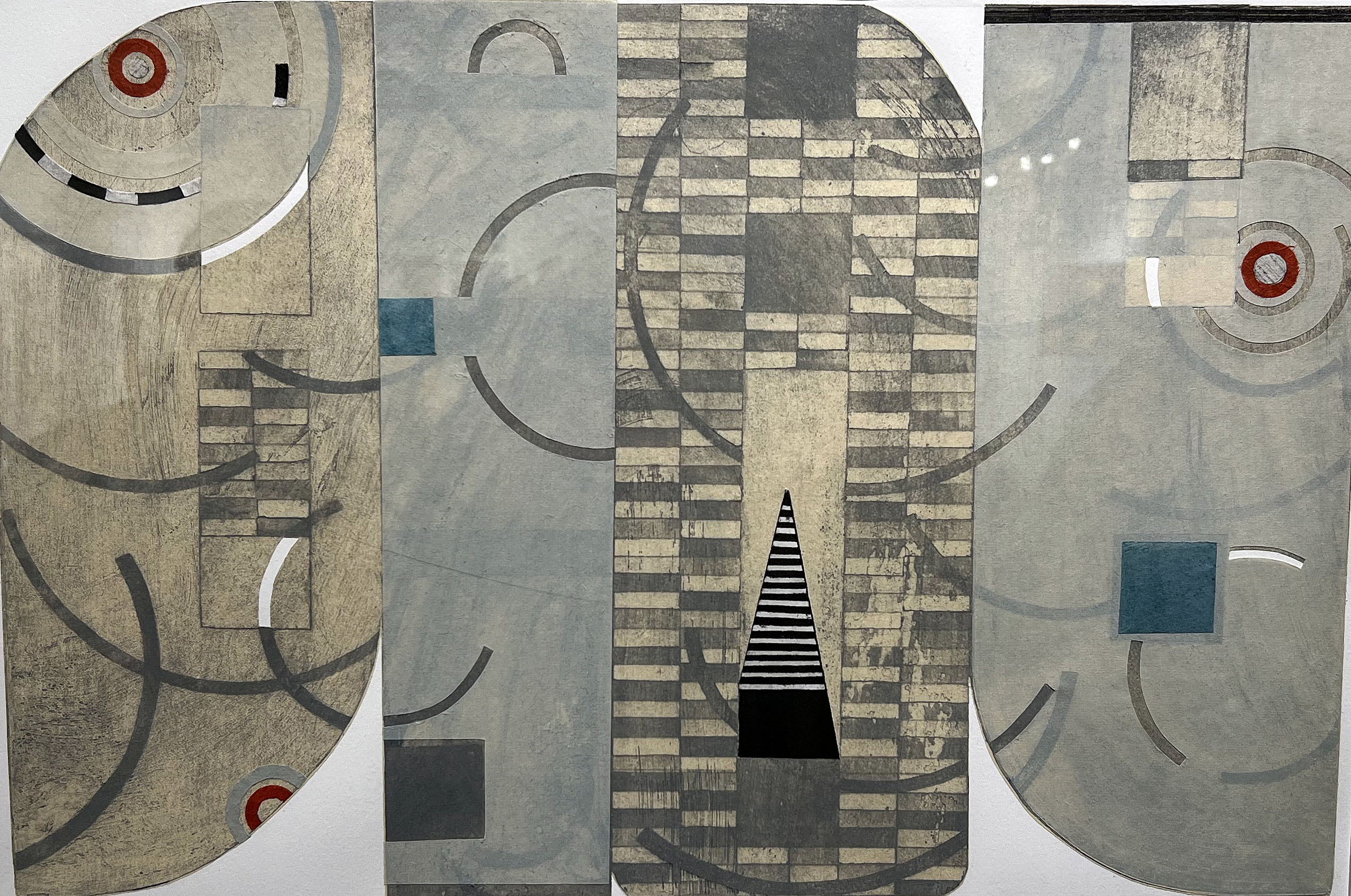

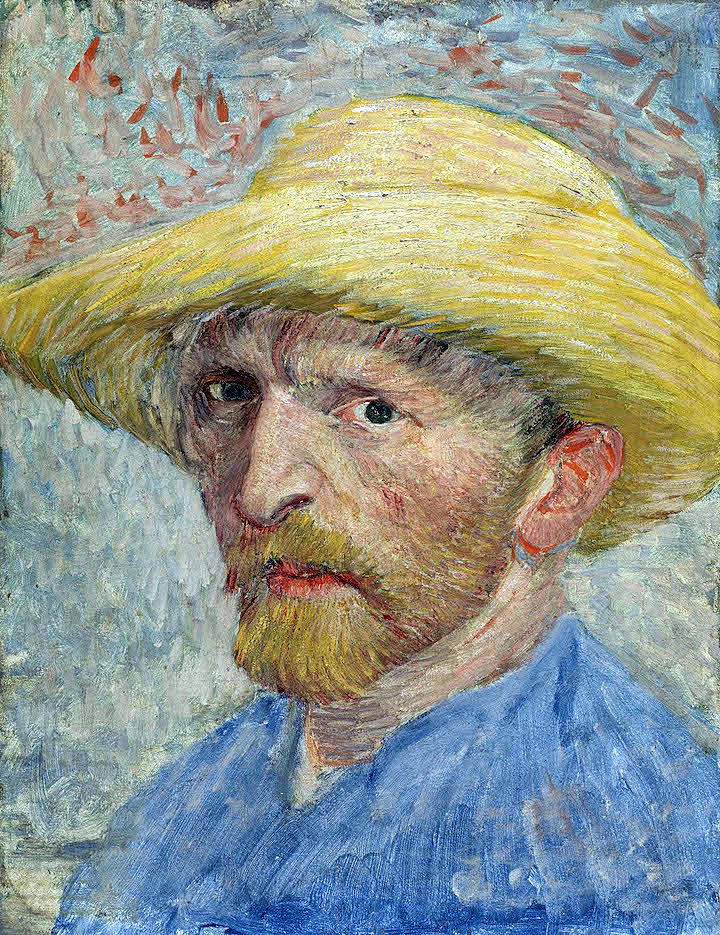

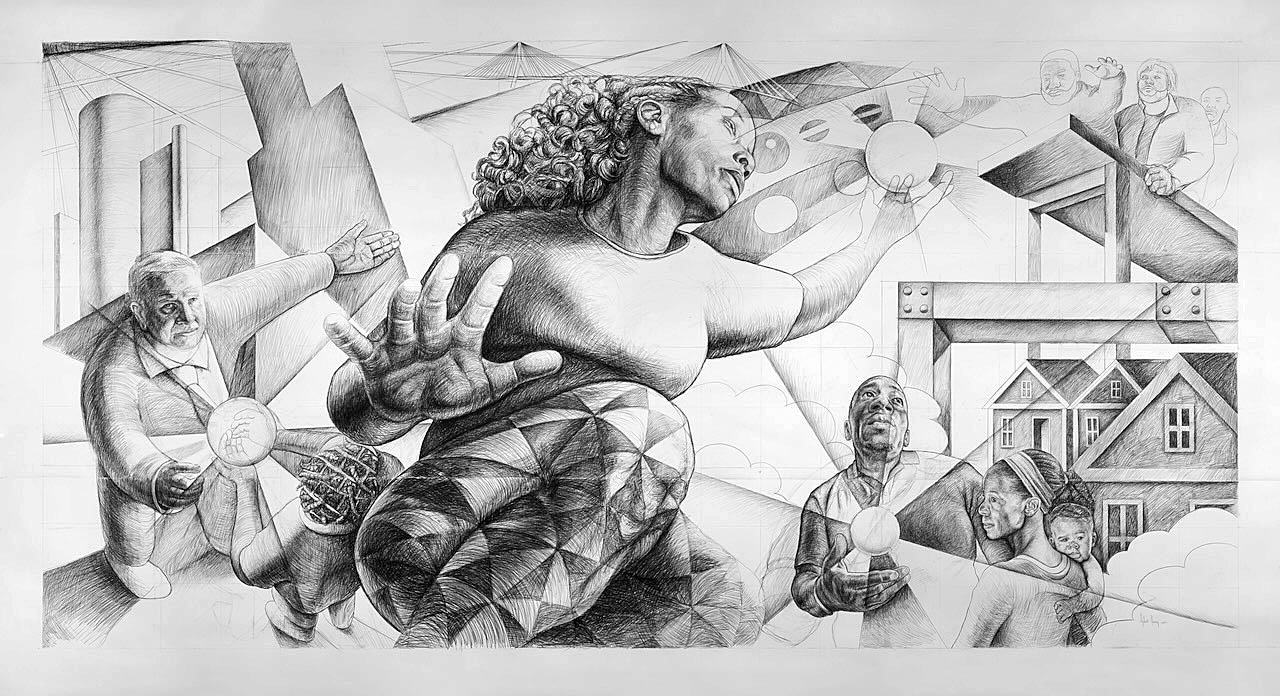

Also grappling with history, though in more sweeping, allegorical fashion, is Hubert Massey’s graphite-on-paper sketch for Forging the Future, a visual explosion of perspective and movement. The resulting fresco now commands the lobby of the new Huntington Tower on Woodward Avenue, just north of Grand Circus Park.

Hubert Massey, Sketch for Forging the Future, Graphite on paper, 2022.

You’re probably familiar with Massey’s work, whether you realize it or not. Among many other Detroit projects, Massey painted the mural on the exterior wall of the College for Creative Studies parking structure at Brush and Frederick streets, and designed the colorful mosaic on the soaring, modernist Bagley Street pedestrian bridge that vaults over the freeway trench dividing Mexicantown.

In pulling together Skilled Labor, Mott said Moore was particularly interested in what he calls “anti-portraits,” depictions that depart from the standard template of subject facing the world. This show has any number of intriguing examples, including several in which the individual in the painting has her or his back turned to the viewer. Consider, for example, Menorah’s Volta: A Light That Speaks by Cranbrook Academy of Art alum Conrad Egyir, a gorgeous portrait of a Ghanaian woman looking away from us, across a vast African valley.

Anti-portraiture emerges in different fashion with Bakpak Durden’s How they recall his hands, an oddly moving portrait of an African-American man operating the wheel of some machine. The most notable feature is there’s no head above the meticulously rendered work shirt – suggesting, perhaps, that Black men were typically valued for their labor, but not for themselves. Durden, a self-taught multidisciplinary Detroit artist, was the subject of a solo show, The Eye of Horus, at Cranbrook in November, 2022.

Bakpak Durden, How they recall his hands, Oil on etch steel, pine, 2023.

A similar motif emerges in Cailyn Dawson’s three portraits on display, two of which clearly feature the artist herself, and one other, the 2021 “Untitled,” that stars a headless figure wearing a trench coat and white shirt. Said Mott, who first discovered Dawson in a show at Ferndale’s M Contemporary gallery, “When Cailyn talks about her work, she talks about learning about herself. She paints to investigate herself.” Assuming, then, that the untitled trench coat is the artist, one could possibly speculate that its meaning lies in a sort of obliteration or enforced invisibility.

Dawson’s other works are equally enigmatic. In “Seeing Double,” the artist regards herself in a mirror, arms and hands visible in the foreground as well as in the reflection. The point of view almost seems to locate us in her body, with the exact same perspective that she’d have on herself. It’s both a bit disorienting and cool. Finally, in Spotlight the artist, who’s currently getting her MFA at New York City’s Hunter College, shields her eyes with one hand from a blinding light that casts a sharp shadow on the white wall behind her. As unexpected compositions go, this almost rises to the level of anti-portrait. As Mott notes, if this were from a photo series, such a squinting image is the one you’d likely toss. That’s no criticism; the very unexpectedness of her pose is what makes Spotlight so hard to look away from.

Cailyn Dawson, Spotlight, Acrylic on canvas, 2021.

Once you’ve made your way through Skilled Labor, which occupies the first, large gallery as you walk through the museum, do turn left into LeRoy Foster: Solo Show. Moore and Mott initially intended to select painters for Skilled Labor from both the 20th and 21st centuries, but ultimately decided it made more sense to focus on works produced in the last 10 years.

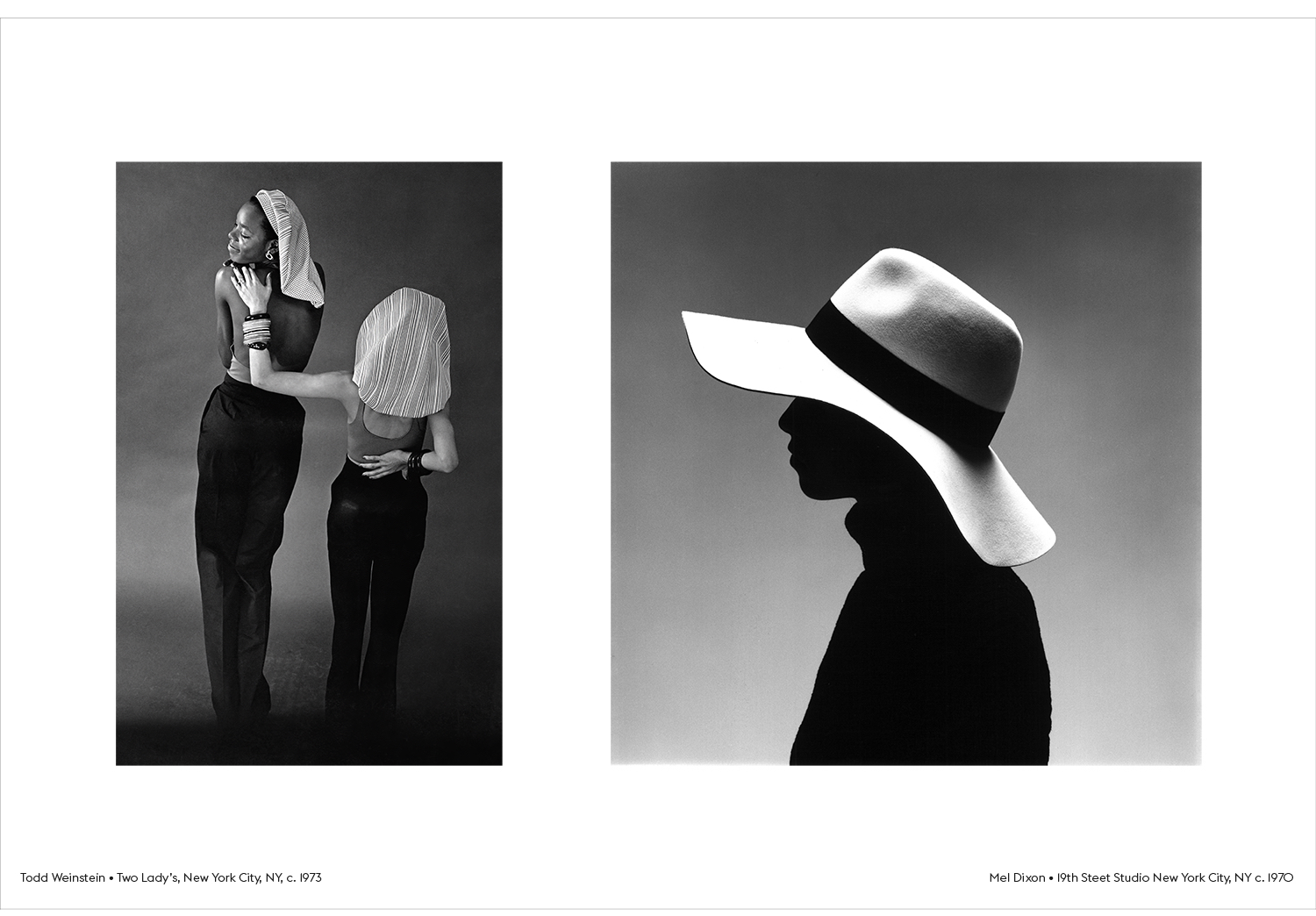

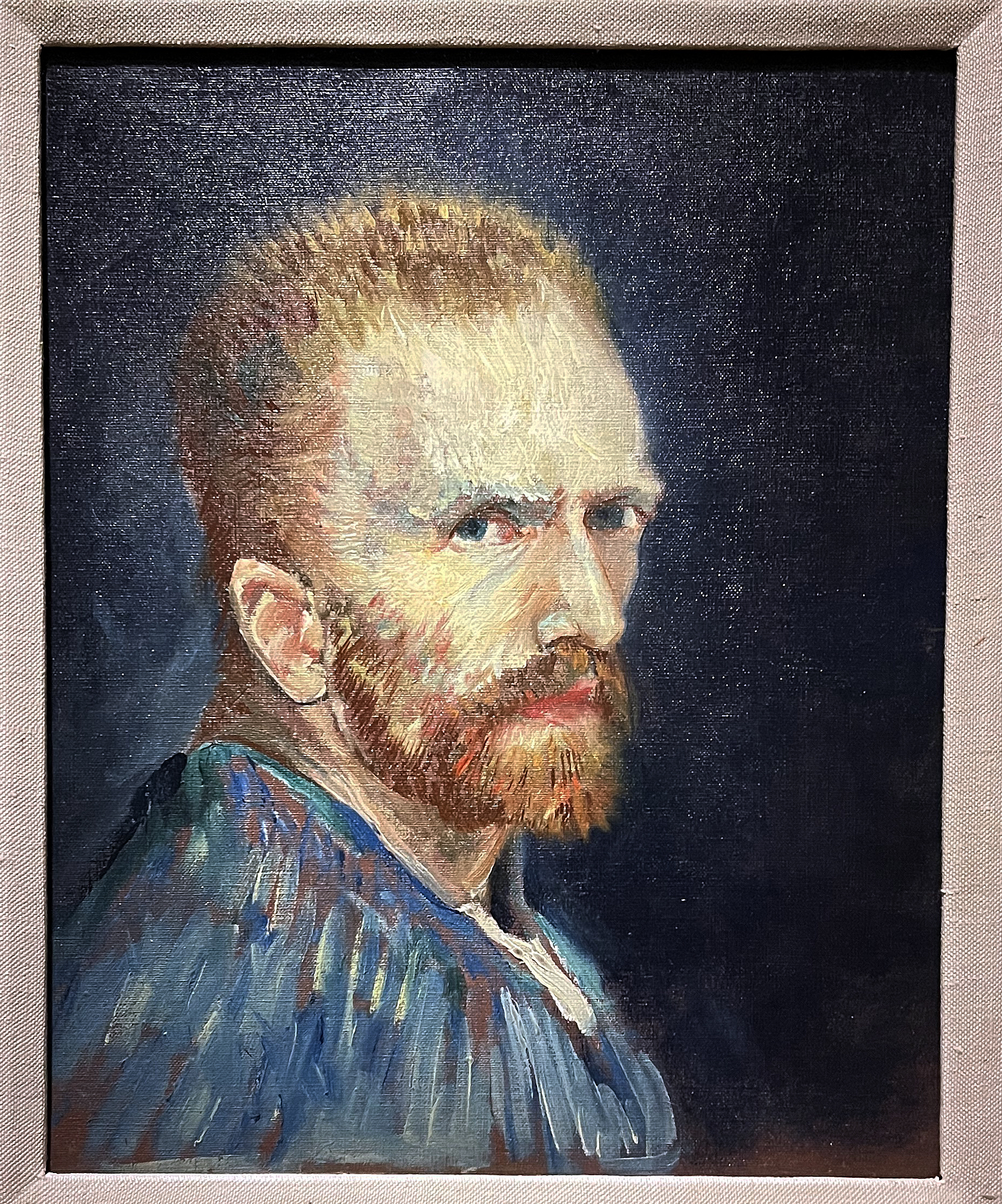

Inevitably, that meant letting go of any number of superb portraitists who are no longer with us. The one exception they made was with LeRoy Foster, born in 1925, whom they decided deserved his first-ever solo show in a museum, one supported financially by the City of Detroit’s Office of Arts, Culture and Entrepreneurship.

Foster, who graduated from the school at the old Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (predecessor to CCS) and probably studied at Cranbrook, is a fascinating and surprising Detroit character – an unapologetically gay, Black artist in an era when that was perilous on any number of levels. In addition, the Detroiter, who lived in an abandoned theater on Livernois Avenue, was a portraitist in an era, particularly the 1950s and 60s, that mostly disdained any figurative art – much less the sort of lush, physicality Foster had such a gift for.

A reporter from National Public Radio, Mott says, wanted to know why an artist of Foster’s astonishing talents wasn’t better known. Mott laughs. “A Black, queer artist in mid-20th Century doing high-Renaissance style portraits? That was the era of Minimalism and Abstract Expressionism. And here’s Foster, hanging out being completely himself, doing paintings the art world at the time would likely have regarded as old-fashioned.”

Foster may be best known for his mural inside the Frederick Douglass branch of the Detroit Public Library – or the one on display in this show, Renaissance City, that hung for years in the old Cass Tech High School, even after the school was abandoned in favor of a new building next door. A group of Cass art teachers, including Senghor Reid (who’s in Skilled Labor) rescued the mural.

Some time after this exhibition closes in early March, Renaissance City will be installed in the new Cass Tech.

LeRoy Foster, Renaissance City, Oil on canvas, 1978/1986.

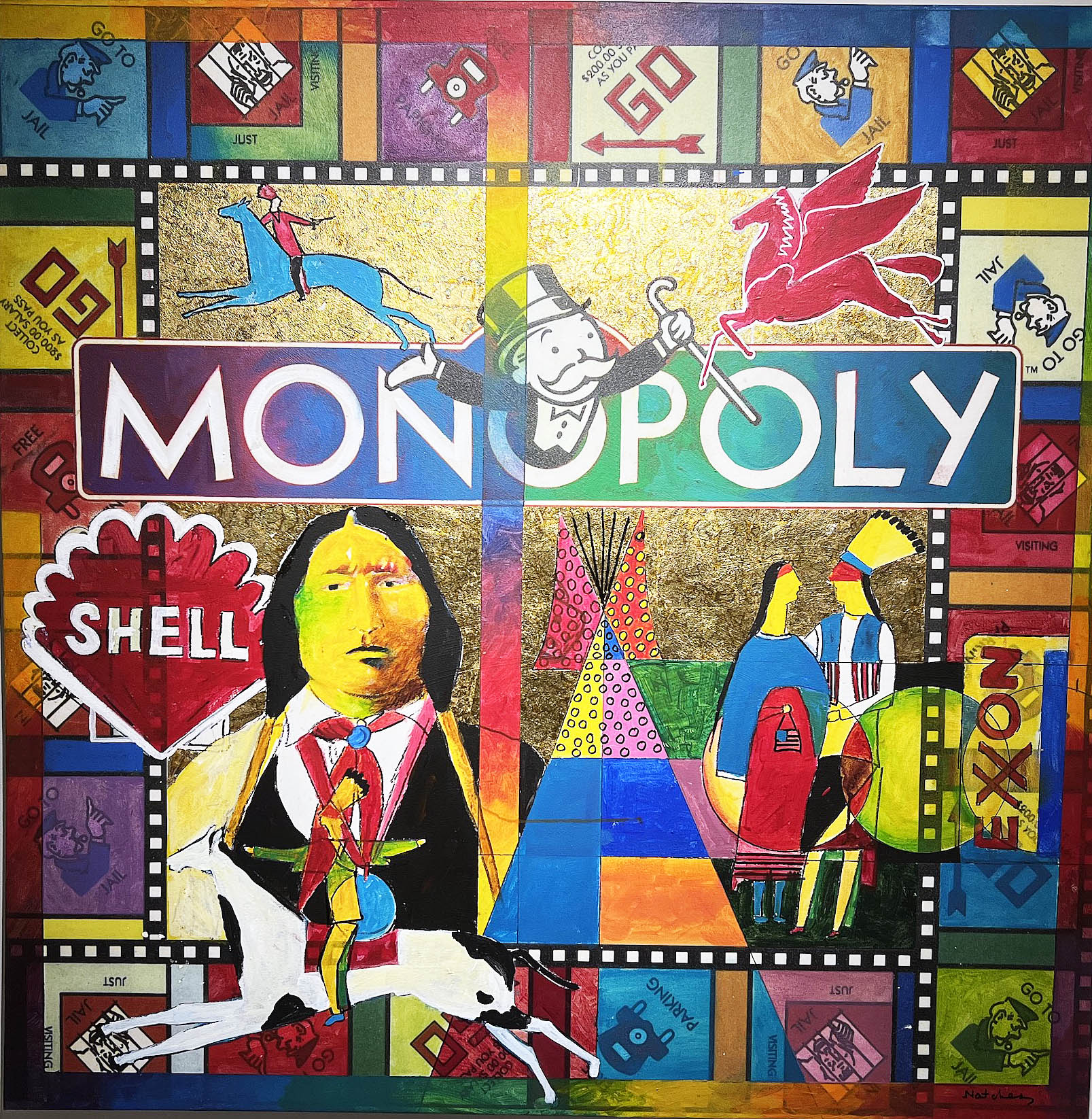

This exhibition features 20 contemporary artists who have worked in Detroit over the last decade. These artists include Christopher Batten, Taurus Burns, Cydney Camp, Ijania Cortez, Cailyn Dawson, Bakpak Durden, Conrad Egyir, Jonathan Harris, Sydney G. James, Gregory Johnson, Richard Lewis, Hubert Massey, Mario Moore, Sabrina Nelson, Patrick Quarm, Joshua Rainer, Jamea Richmond-Edwards, Senghor Reid, Rashaun Rucker, and Tylonn J. Sawyer.

Skilled Labor: Black Realism in Detroit and LeRoy Foster: Solo Show will both be at the Cranbrook Art Museum through March 3, 2024.