Echoes from the Rust @ Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Wayne State University

“Echoes from the Rust,” Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Exhibition installation. All photos by K.A. Letts

It’s a tall order to ask a few to speak for the many, as these six artists from Detroit and Pittsburgh have been chosen to do in the exhibition “Echoes from the Rust,” on display at Elaine L. Jacob Gallery until January 10, 2025. The expansive theme of resilience in the face of hardship and of the importance of ethnic identity, immigration, labor, and location in the region’s artistic production could easily encompass the stories of 60 artists…or six hundred. But these half-dozen accomplished makers of images and objects, selected by independent curator Kemuel Benyehudah, describe as well as anyone can how midwestern values are shaped by personal experience, geographic displacement, and economic adversity.

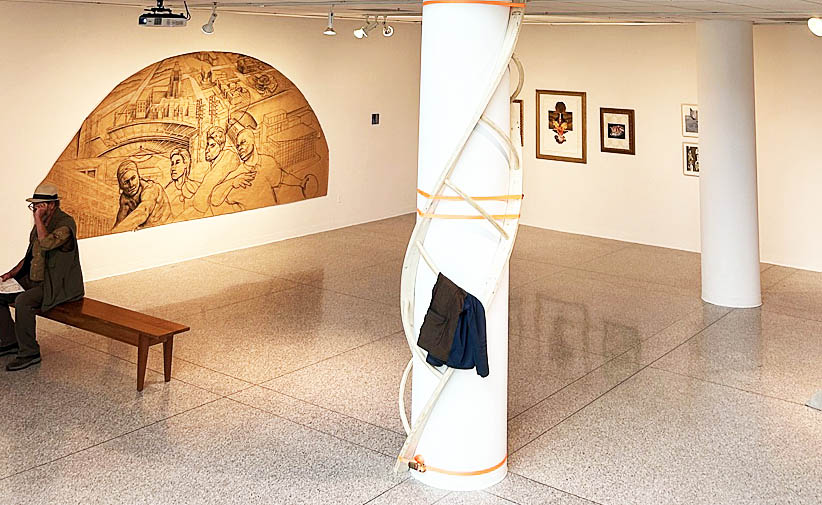

Hubert Massey, Cityscape of Detroit, 1999, charcoal drawing on paper.

Narrative art enjoys exceptional credibility in the Midwest, where the ghosts of Thomas Hart Benton and Diego Rivera lurk in the consciousness of several of the exhibition’s artists. Eminent Detroit muralist Hubert Massey’s reverence for the craft of drawing is evident in the two semi-circular charcoal works on paper displayed on the gallery’s main floor. In these preparatory drawings for his frescos in the Detroit Athletic Club, carefully rendered architectural features of Detroit form a backdrop for monumental figures that would be at home in a depression-era WPA mural. N.E. Brown, of Pittsburgh, likewise traffics in the archetypal, with meticulously painted scenes of workers that range from the miniscule “Blue Collar” to “The Mill,” in which a masked and gloved worker rendered in burnt wood to graphically evokes the heat and dim light of an industrial environment.

N.E. Brown, Blue Collar, 2024, oil on canvas.

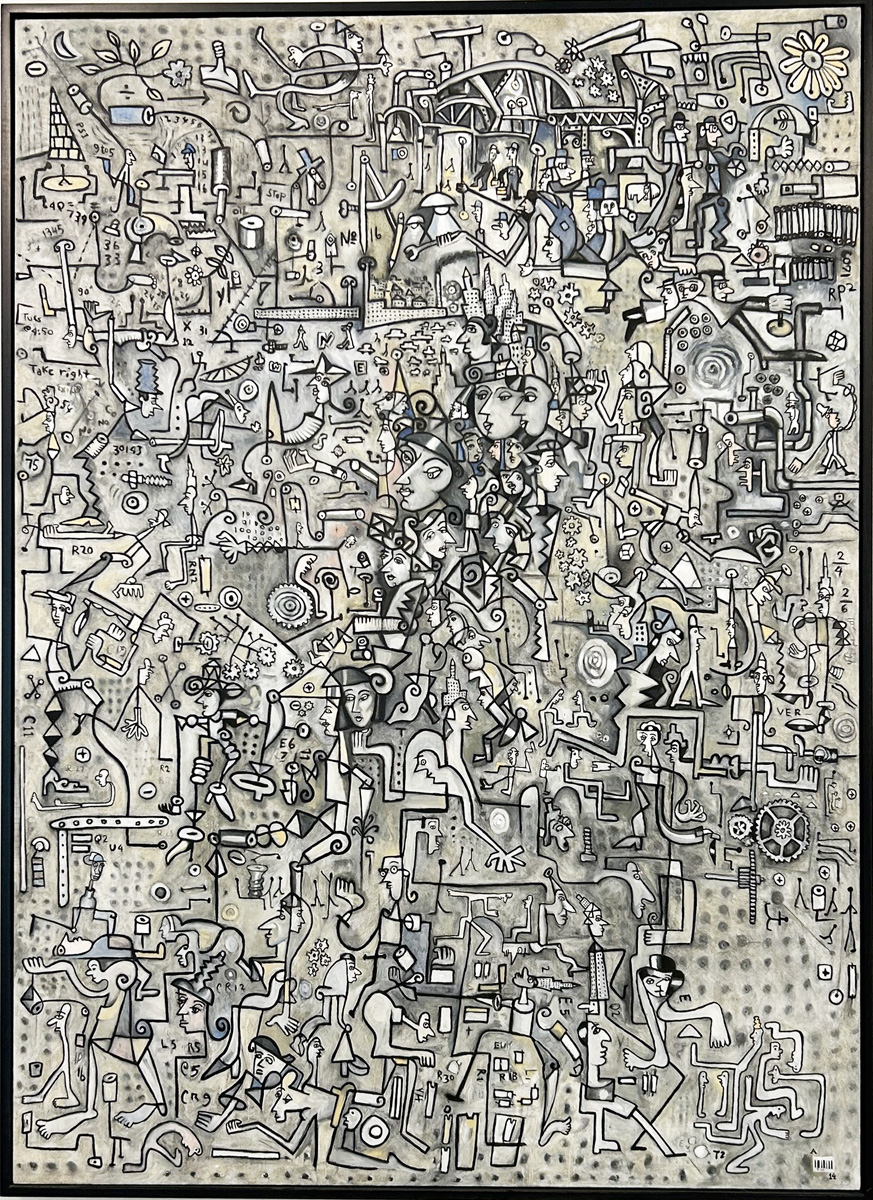

Like several other artists in the exhibition, Adnan Charara is an immigrant delivered in 1982 to Detroit by political upheaval in his native Sierra Leone. Charara’s family of Lebanese descent found a home in the Middle Eastern diaspora of Dearborn, while the artist himself found a vocation in fine art after completing his education in environmental studies and urban planning. Charara is that odd combination of a highly educated, yet self-taught, artist. Through his extensive self-guided studies, he has arrived at a style of expression that seamlessly combines a variety of art historical styles with his comic sensibility.

Adnan Charara, Unconscious, 2006, oil on canvas.

Charara’s three black and white silkscreen prints of workers, created in 2014, are reminiscent of Diego Rivera’s DIA murals, but represent less an homage to Rivera than Charara’s direct observations of industrial workers from the same source materials. Two large canvases, more typical of his current style, are wiggly, jittery masses of small figures crawling over and across a more-or-less undefined, yet urban, space. Hieronymous Bosch might recognize and approve of the anxious yet optimistic citizens of this no man’s land.

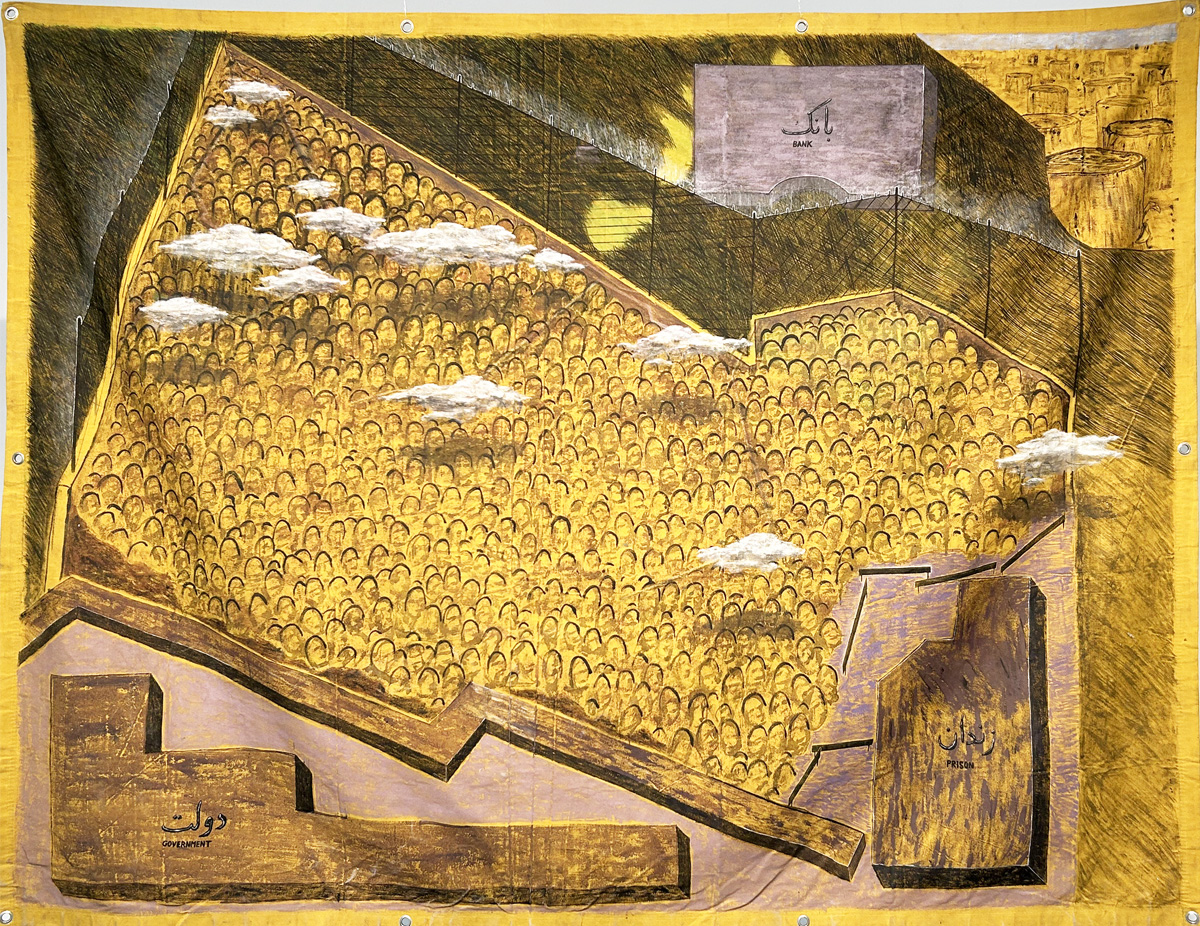

Omid Shekari, Is there a way Out, 2023, acrylic on industrial canvas.

Omid Shekari, another global transplant, arrives at the gallery from Iran by way of Pittsburgh. Displaced by the political upheavals in his native country, Shekari vividly remembers his experience as the victim of an oppressive regime, a past that continues to shape his art practice. He says, “My work looks at power and questions the levels of violence that it causes, as well as possibilities to resist such a phenomenon.”

Shekari’s musings on questions of political power and its oppressive use take form as imaginary architecture, metaphors for the cultural and political structures that imprison humanity. Seen as if from above, Body – Nation – State’s wall-mounted metal structure evokes a dream-like sense of displacement juxtaposed with a brutal reminder of human vulnerability. In the middle of this miniature built environment, a small piece of meat adds a jarring note of corporeality. Human fragility hangs suspended and displaced, surrounded by an edifice both shadowy and solid. The same aerial point of view shows up in Shekari’s painting Is There a Way Out, depicting a claustrophobic vision of a nation imprisoned. The same theme is revisited in his metal sculpture, Nation [government-bank-armed forces-prison] State, a seemingly impenetrable labyrinth for holding in –or keeping out–something. Is it information? Free thought? Free expression?

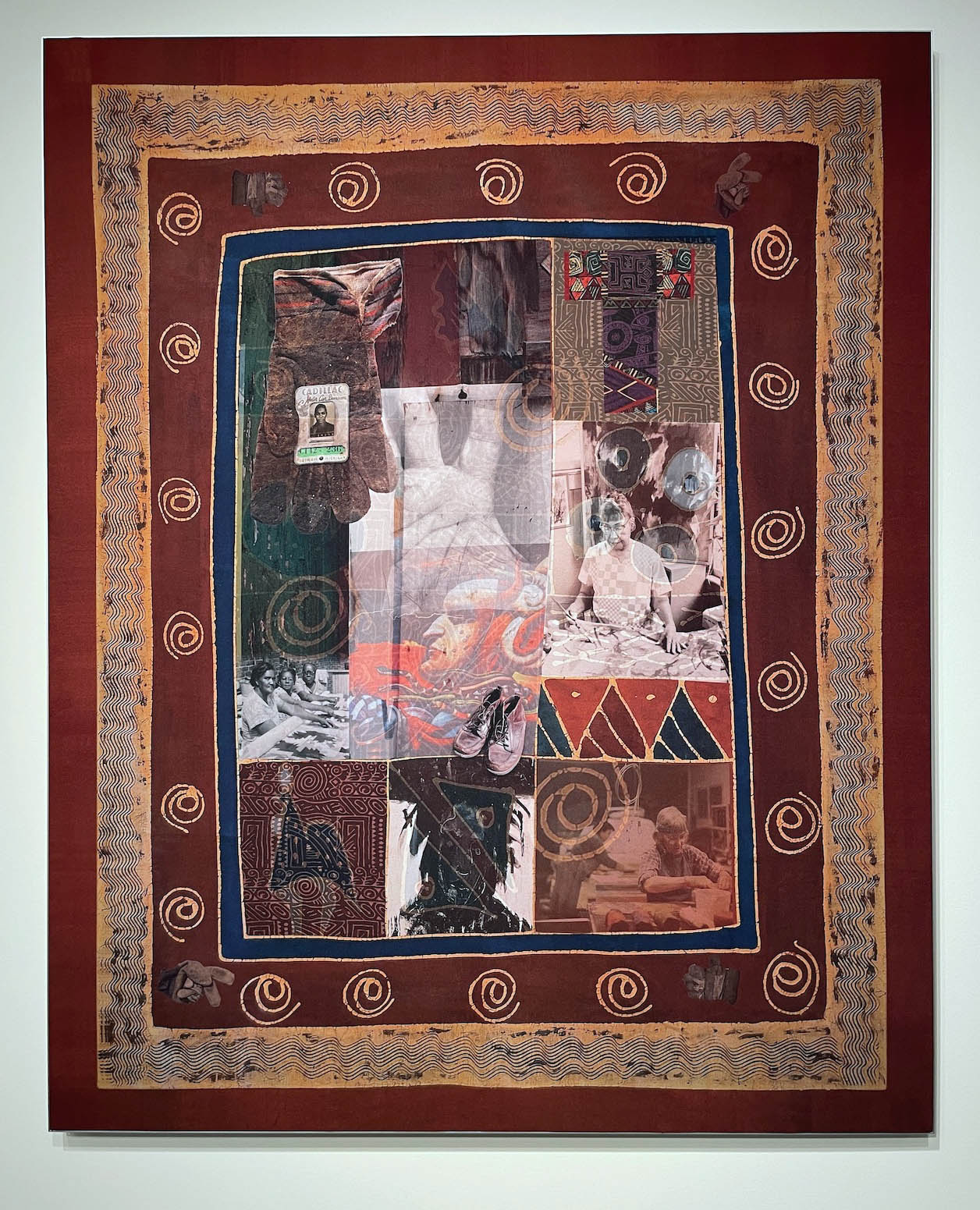

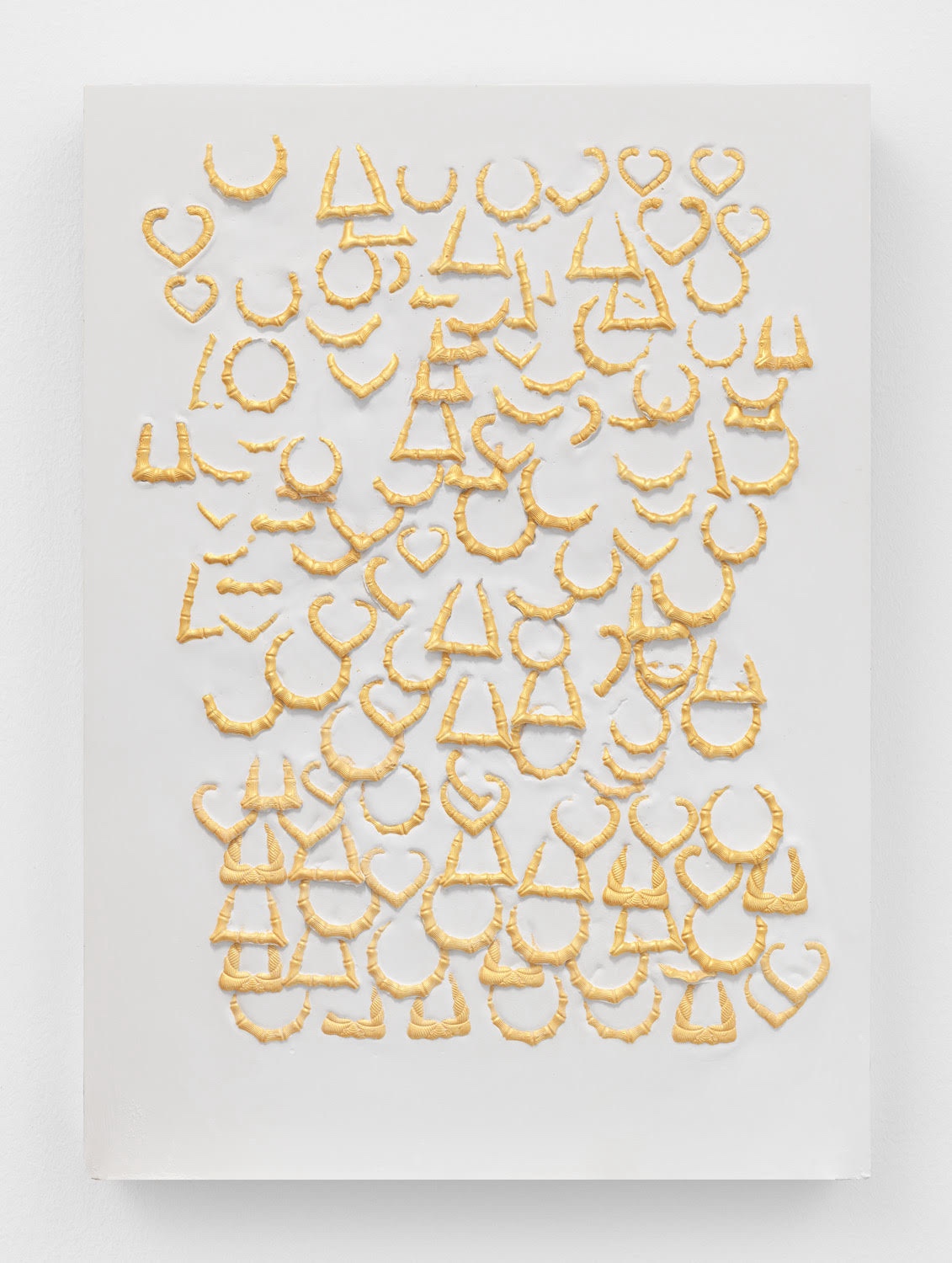

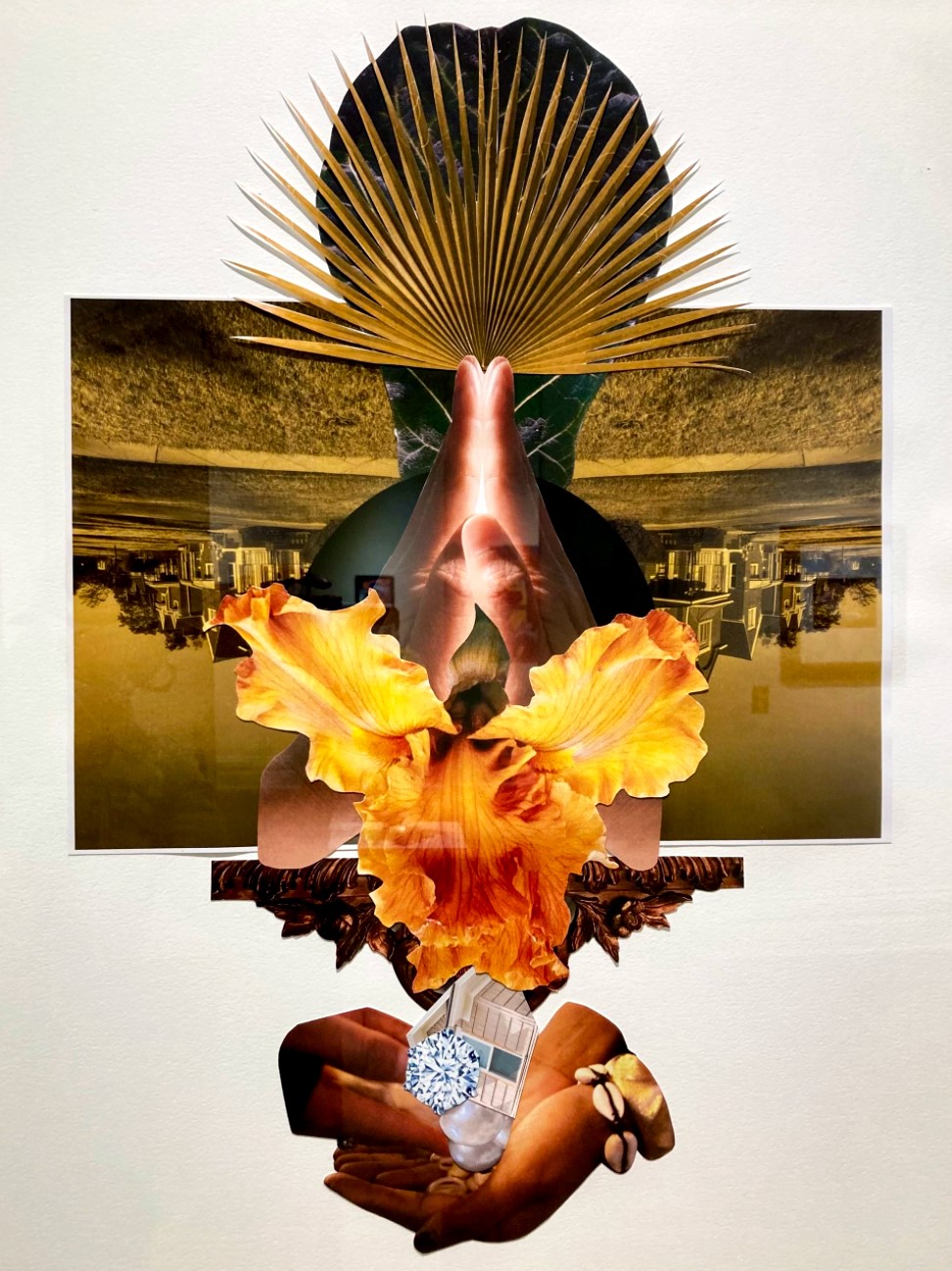

Halima Afi Cassells, Gold Cash Gold, 2024, paper cut.

Halima Afi Cassells views the state of the Midwest with guarded optimism through the lens of her deep cultural roots in the city of Detroit. Her carefully crafted paper cuts acknowledge the importance of technical mastery in a region known for making things. Three delicate artworks privilege the aesthetic over the political, but her strong social justice message is fully displayed in her 17-minute video, Detroit Future State. Composed of two parts, Detroit Future State is a polemic in which the ideal is contrasted with the real. In the first part of the video, an elegantly clothed and coiffed Cassells describes a utopian Detroit future as if it has already come to pass, with community gardens, abundant housing, and adequate healthcare. At the end of this blissful description, Cassell trades her fashionable costume for down-to-earth street clothes and delivers—in black and white–a wry description of things as they actually are in the city.

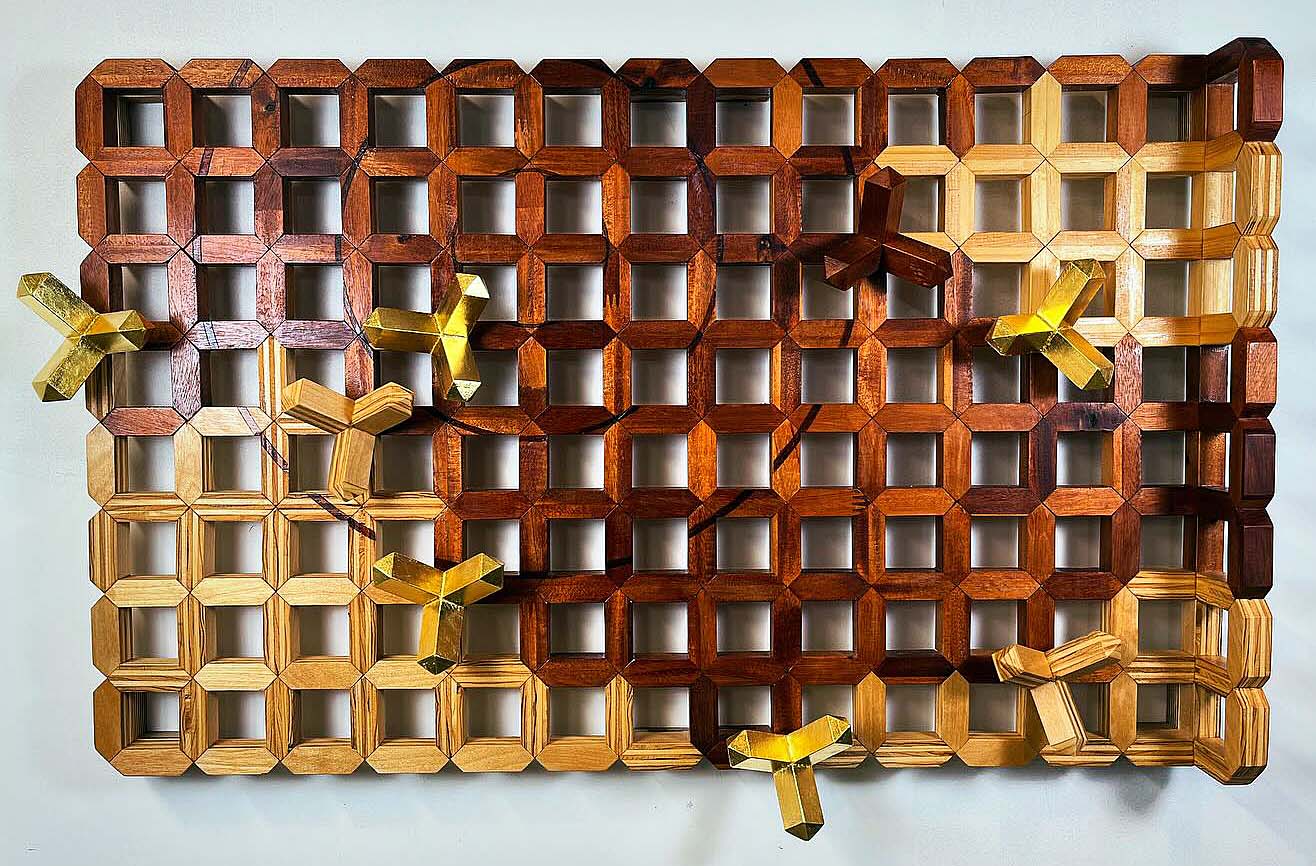

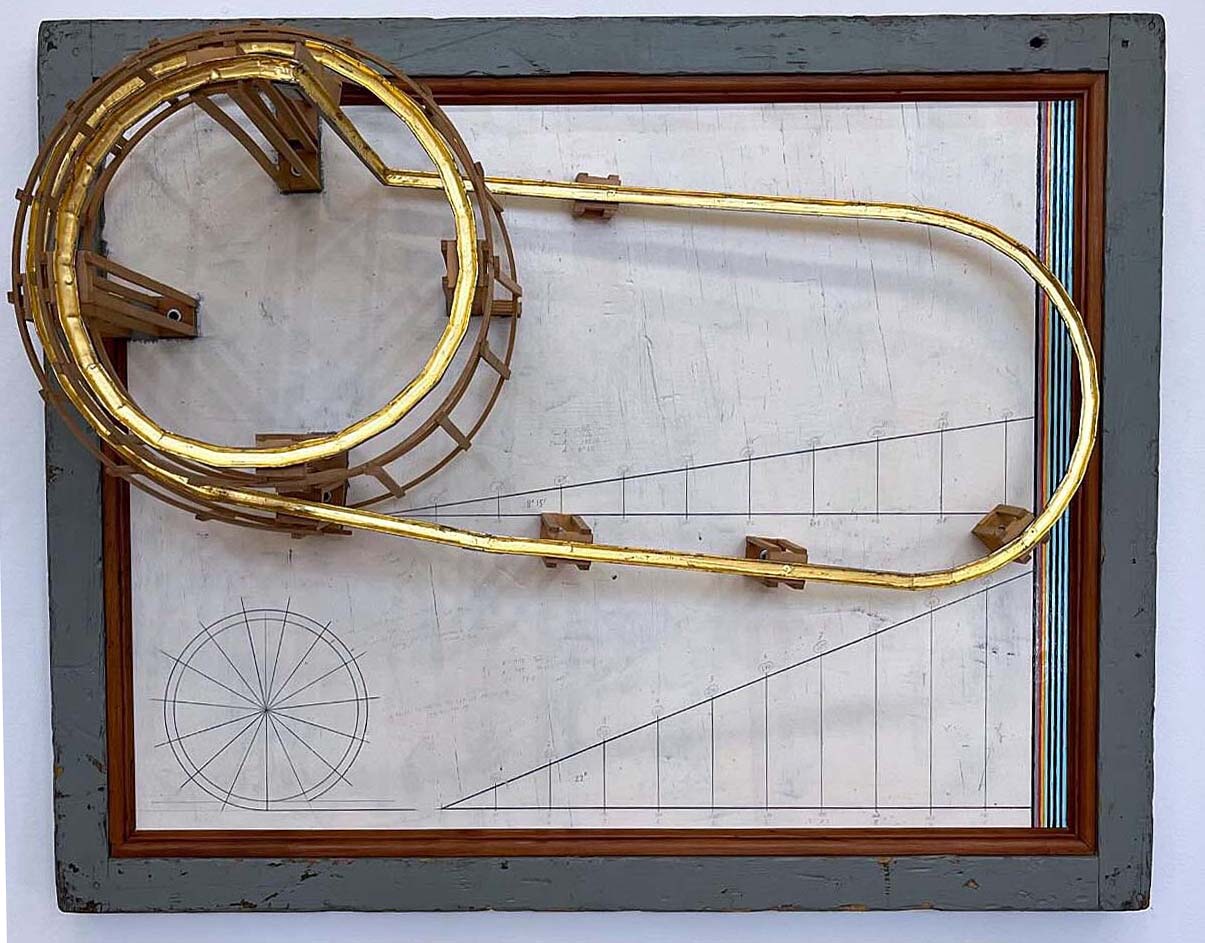

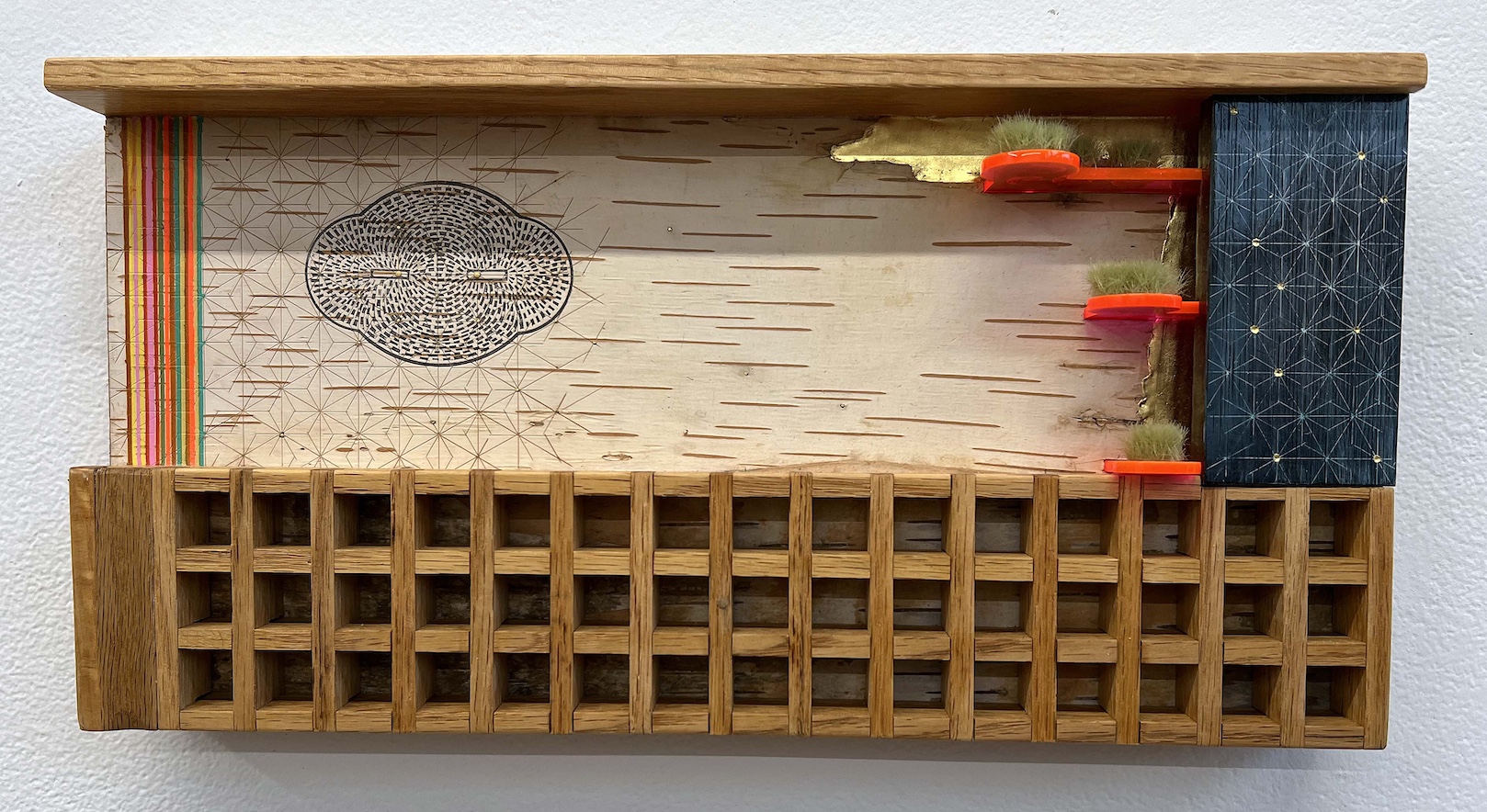

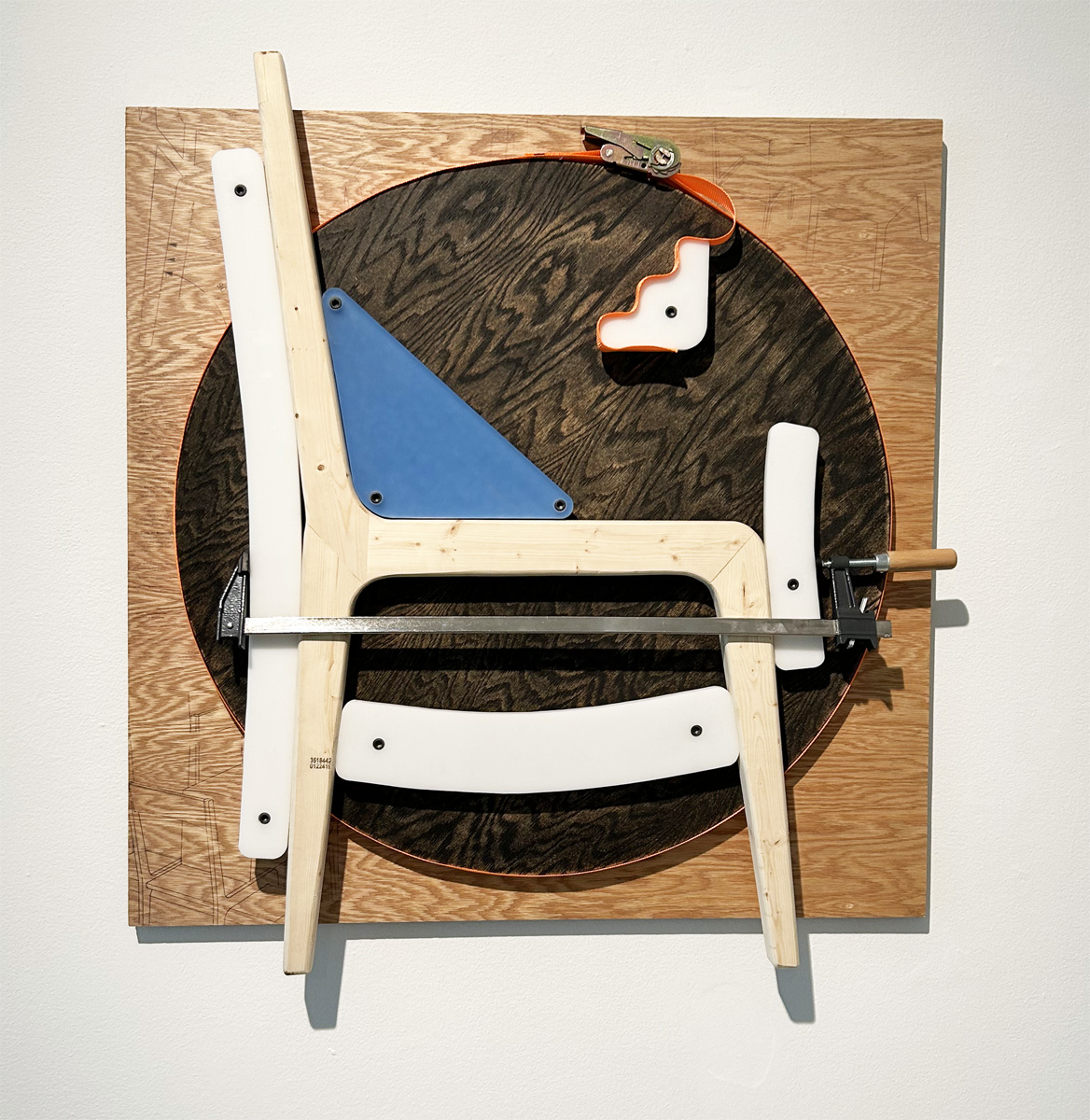

Josh Challen Ice, Held Together, 2024, plywood, plastic, construction lumber, ratchet strap, blue tape, inkjet print.

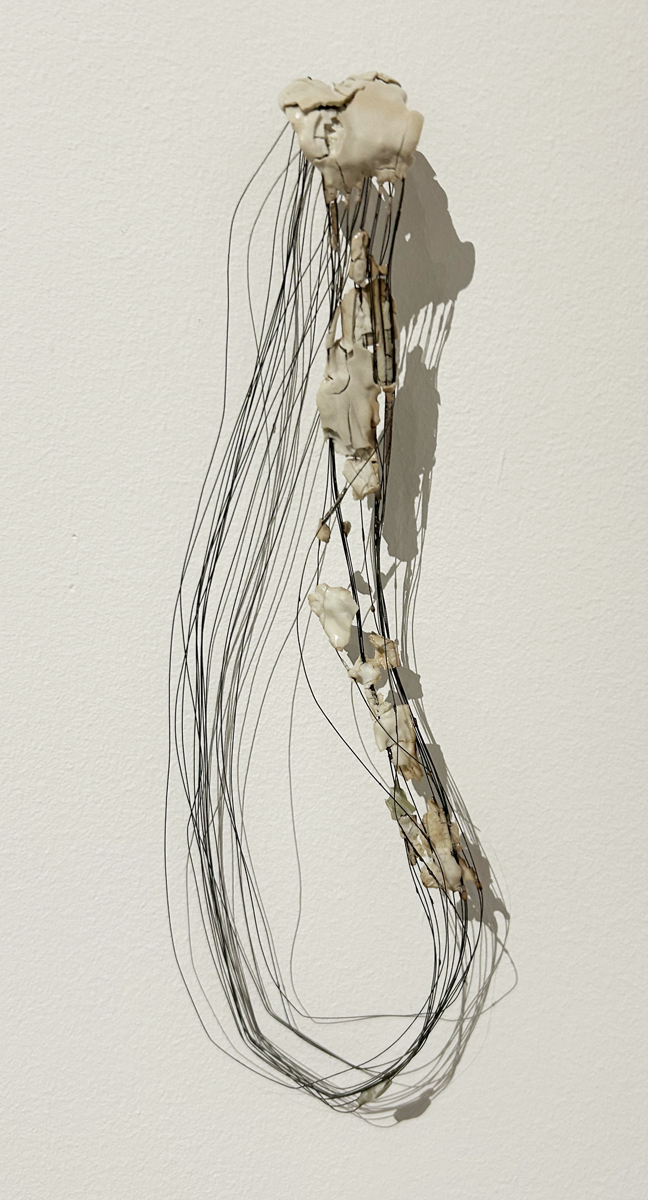

The exhibition’s underlying theme honors the importance of labor in defining the soul of the rustbelt, past and present. It finds its most elegant expression in constructions by Pittsburgh artist Joshua Challen Ice. Ice honors the value of beauty and the importance of craftsmanship in the making of things. He creates each object and installation, often from upcycled materials, with precision while leaving evidence of his labor in the form of clamps, stamps, and straps. His remarkable sculpture, Held Tight, is an impressive example; it replicates the shape of a strand of DNA beginning at ground level and traveling upward. Beautifully created in wood and wrapped around one of the gallery’s central pillars, the construct echoes the architecture of the spiral staircase nearby. Left on one of the crosspieces, as if by accident, is a workman’s jacket, a reminder that these unique and impressive objects are made by someone.

“Echoes from the Rust” is an exhibition in which superior technical and formal expertise serves the artists’ progressive vision. Each artist’s output reflects, in its own way, a shared ethic of hard work, craftsmanship, and social justice. There is an abiding optimism in the work that describes an often neglected part of America, brought together here in a celebration of resilience and grit.

“Echoes from the Rust,” Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Installation. Background: Hubert Massey Cityscape of Detroit, 1999, charcoal drawing on paper. Foreground: Josh Challen Ice, Absent Hands, 2024, construction lumber, ink stamp, concrete.