Detroit Artist Allie McGhee exhibits a Retrospective, Banana Moon Horn, at Cranbrook Art Museum

Installation image, Allie McGhee, Retrospective, Banana Moon Horn, at Cranbrook Art Museum, all images courtesy CAM

Cranbrook Art Museum (CAM) opened a retrospective exhibition of artwork by artist Allie McGhee on October 30, 2021, which spans five decades of work produced at McGhee’s Jefferson Avenue studio in Detroit.

Laura Mott, the chief curator of contemporary art and design at Cranbrook Art Museum, curated the exhibition. She says, “My interest in Allie McGhee’s work came from seeing his paintings at local galleries in Detroit, but when I did my first studio visit with him, it was a revelation. In his studio, I saw decades of work and an incredible arc of his artistic practice since the 1960s. There is also a richness of ideas in his methods of production and research into history and science. When one encounters an incredible mind like Allie’s, it becomes a necessity to tell his story. Furthermore, his work needed to be contextualized in art history, which is why it was important to have both an exhibition and publication.”

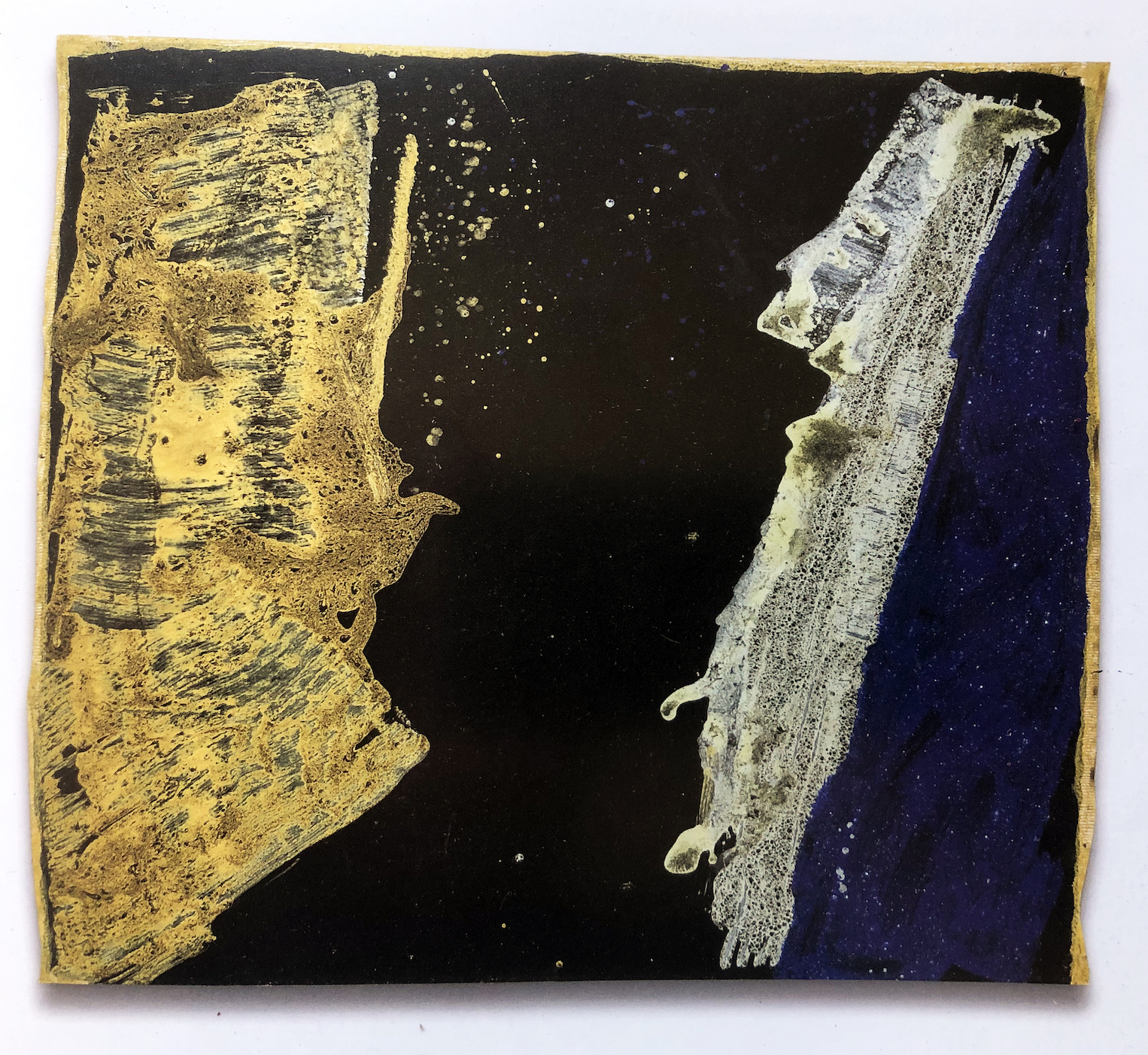

The exhibition brings together artwork that demonstrates the evolution of McGhee’s work back to the 1960’s, beginning with early representational work that quickly evolved to abstraction. McGhee’s work was heavily influenced by trends in the abstract expression movement and influenced by jazz musicians in the Black community.

Andrew Blauvelt, director of Cranbrook Art Museum, said of some of McGhee’s work, “Learning of McGhee’s interest in astronomy, their crumpled and twisted forms have taken on a new resonance, one that recalls the spatial complexities of Catastrophe theory and, in particular, the relative notion of the fold.”

This exhibition takes on more than forty years of paintings and drawings and documents the growth of one of Detroit’s most important artists. The museum produced this short 6-minute video as an introduction to Allie McGhee and his work.

From his recent talk at Cranbrook, the story goes that McGhee came upon an object in the street that reminded him of a KKK hood. The object was an icing cone used in a bakery. This occurred in a time period just a year or so after the 1967 Detroit Rebellion and caused McGhee to harness that energy and create an object that hung on the wall alongside a petrified banana, foreshadowing what would repeat itself for years to come.

Allie McGhee, The Ku Klux Klown, Mixed Media on found object, petrified banana, 1961. All images courtesy of CAM

Ku Klux Klown coincided with his association with a black artist cooperative founded by Charles McGee. Charles organized the landmark 1969 exhibition Seven Black Artists at the Detroit Artists Market and founded Gallery 7. Along with Allie McGhee, members included Lester Johnson, Robert Murray, James Lee, Harold Neal, and Robert J. Stull. For years, Allie McGhee pursued abstract expressionism using a variety of sizes, shapes, and materials on a flat canvas that hung on the wall. The object and the banana became the center of what was to be called Banana Moon Horn, the title of this exhibition and the Cranbrook publication.

Allie McGhee, TWA Light on Washburn, Mixed Media on canvas, 1989

One of the strongest compositions in the exhibition was from 1989. TWA Light on Washburn, repeats the reoccurring banana symbol that follows him over time. One of the trademarks of McGhee’s work is that he leaves behind the use of traditional brushes for flat sticks of varying sizes to move paint across the surface. In addition, he has a variety of tools to remove paint from a given area, be it cloth, wood or plastic. This could easily have been when he preferred placing the canvas on the floor instead of using an easel to hold the stretched canvas on a frame. Gravity is his friend on the floor, not an obstacle, where mixing paint worked to his advantage. In TWA Light on Washburn, we see the primary colors dominating the composition while using the spacing of thirds on the grid, both vertical and horizontal. There is no evidence of brushwork on the canvas, only the stroke of a long stick he used to create geometric lines, shapes, and sometimes texture. Various values of red, blue, and yellow assist in holding everything together.

Allie McGhee, Apartheid, Mixed Media on Masonite, 48 x 120″, 1984

Most recently viewed in 2017 at the Detroit Institute of Arts as part of a large exhibition, McGhee’s Apartheid was on display in the Art of the Rebellion and Say It Loud, commemorating 50 years since July 23, 1967, when African Americans took to the streets of Detroit to express their anger and frustration with the injustice of law enforcement. It would come to be called the Detroit Rebellion. McGhee’s work was then being shown by the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art. This painting highlights his use of angular shapes and splatters of paint to evoke and represent the tension of the time. The title Apartheid refers to the oppressive political system that existed in South Africa. The Civil Rights and Black Power movements inspired many African American artists to internalize the fight for civil rights in Detroit.

Allie McGhee, Fall Rush, Acrylic on enamel paper, 2013

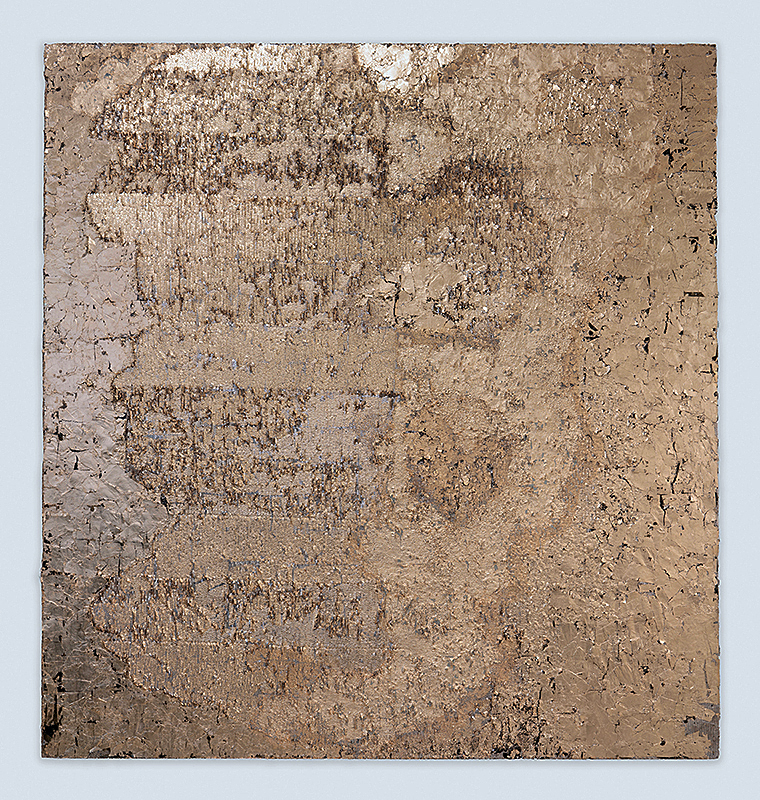

Throughout his talk at Cranbrook Art Museum, McGhee continued to stress and talk about his approach. “ The process is more important than the subject.” Thanks to his diligent years of daily work, we see the artwork on the floor begin to evolve and ultimately create something very new. The work Fall Rush (2013) is acrylic and enamel on paper where McGhee has applied his sensibility to both sides of this heavy-duty paper and then worked on producing a crushed and folded object that would present itself on the wall. When I first viewed the work, my only context was the artwork by sculptor John Chamberlain who did something similar with scrap metal, usually mounted on a base as in Homer, 1960. Chamberlain didn’t paint the metal, instead, he would find parts from scrap car lots where he discovered his colors in the parts of fenders and related shapes of metal. Here, McGhee, the painter, created his own material by painting both sides of the paper, canvas or vinyl, and inventing his shape using his well-developed sensibility. He puts his trust in the process.

Allie McGhee, Flip Side, Acrylic on enameled vinyl, 2015

In the piece Flip Side (2015), we see the evolution of this work where he adds elements after the object is created and on the wall. During the artist talk, he mentioned his interest in science and the various visual aspects of the universe, either through a telescope or a microscope. McGhee mentioned participating in an Art & Science program that paired artists with scientists from the University of Michigan. The artists then made an artwork that was auctioned off to support scientific research. McGhee was seeking information based on scientific discovery where he sought truth and imagery in the cosmos.

And Allie McGhee talked briefly about the role of music in creating art with an emphasis on the Black jazz musicians John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, and Charles Mingus. They all co-mingled with his process.

Russian abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky has said he was deeply inspired by music. He played the violin from an early age and even gave his works of art musical titles: ‘Improvisations’, Compositions’ and ‘Fugue.

I know I carefully select what I play in my studio. I always select instrumental-only by a variety of musicians like Dave Brubeck, Mozart, or Arvo Part.

Richard Dorment, the art historian, said of Paul Klee, “He started every picture with an abstract mark—a square, a triangle, a circle, a line or a dot—and then allowed that motif to evolve or grow, almost like a living organism.” Whether it is from subconscious dreams or Eric Dolphy on the Saxophone, Allie McGhee worked daily to the sound of jazz. The improvisational riffs provided support for the creation of rich abstraction in the studio, experimenting with materials, making the same mistakes over and over until something emerges and falls into place or rises to the top. What resonates in my thoughts is McGhee’s emphatic statement, “It’s the process, not the subject.”

In the Cranbrook publication, McGhee says, “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It is an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks labored and overworked, and you can’t read in it…there is something in there that has not got to do with beautiful art. And I usually throw these out, though I think very often it takes ten of those over labored efforts to produce one really beautiful wrist motion that is synchronized with your head and heart, and you have it and therefore it looks as if it were born in a minute.”

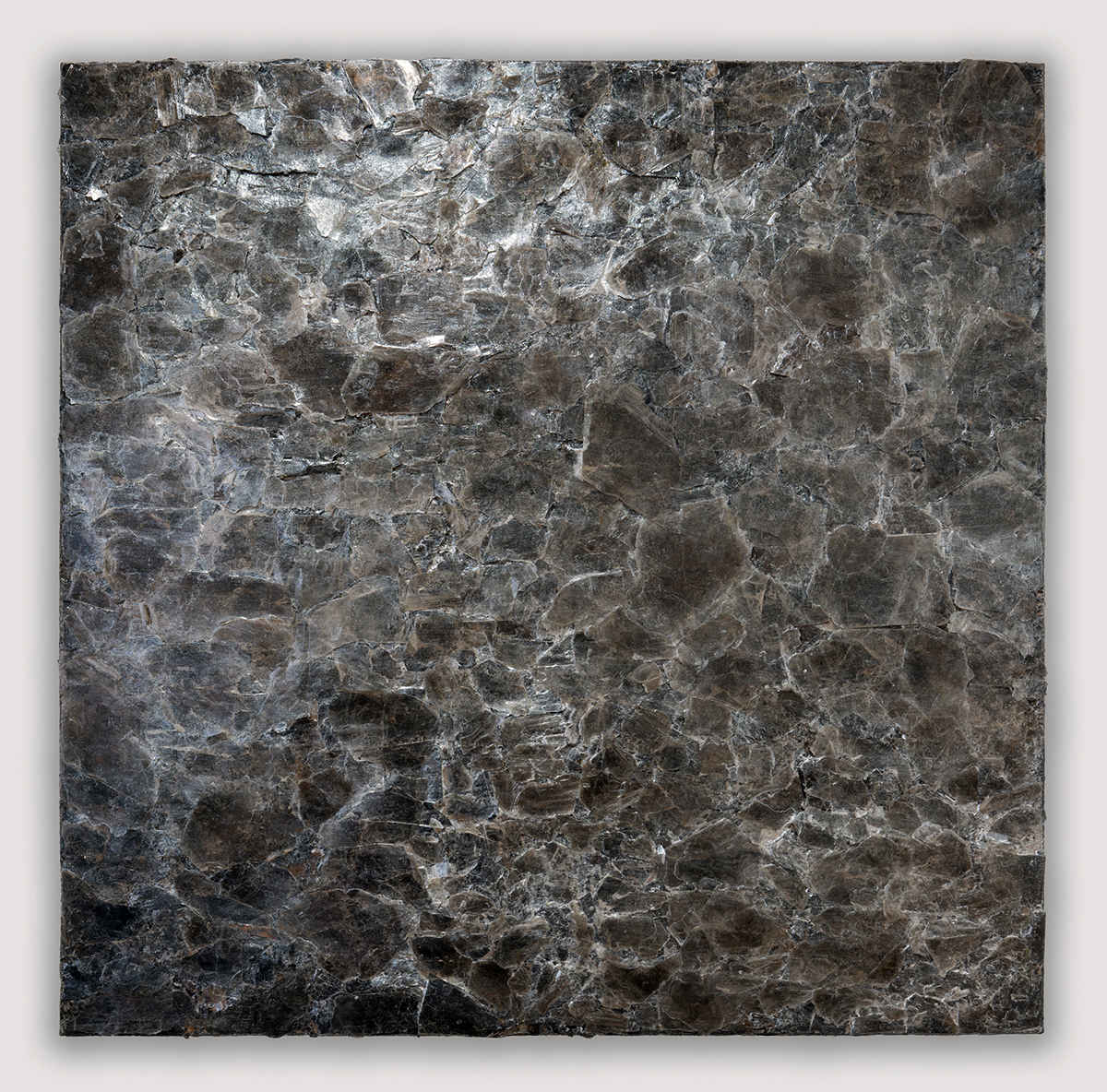

Allie McGhee, Bloom, Acrylic, and enamel on fiberglass, 2019

In the acrylic and enamel on fiberglass Bloom, McGhee gives the viewer some insight with the title and adds details to the piece after its painted and folded creation. Who knows? The inspiration may have come from a memory of sitting at his mother’s kitchen table where some flowers were blooming in a vase. We see the surface where the artist draped and dragged the stick over the fiberglass on the floor, then the folding produced fluidity and pattern.

Laura Mott quoted McGhee in her writing about him as saying, “I can tell stories in my paintings about these significant contributions made through our history. To me, that’s a lot more exciting scientifically, spiritually, and visually to feed off of. It’s never-ending. The only limitation is the entire cosmos…I don’t think I will be able to use that up in my lifetime.”

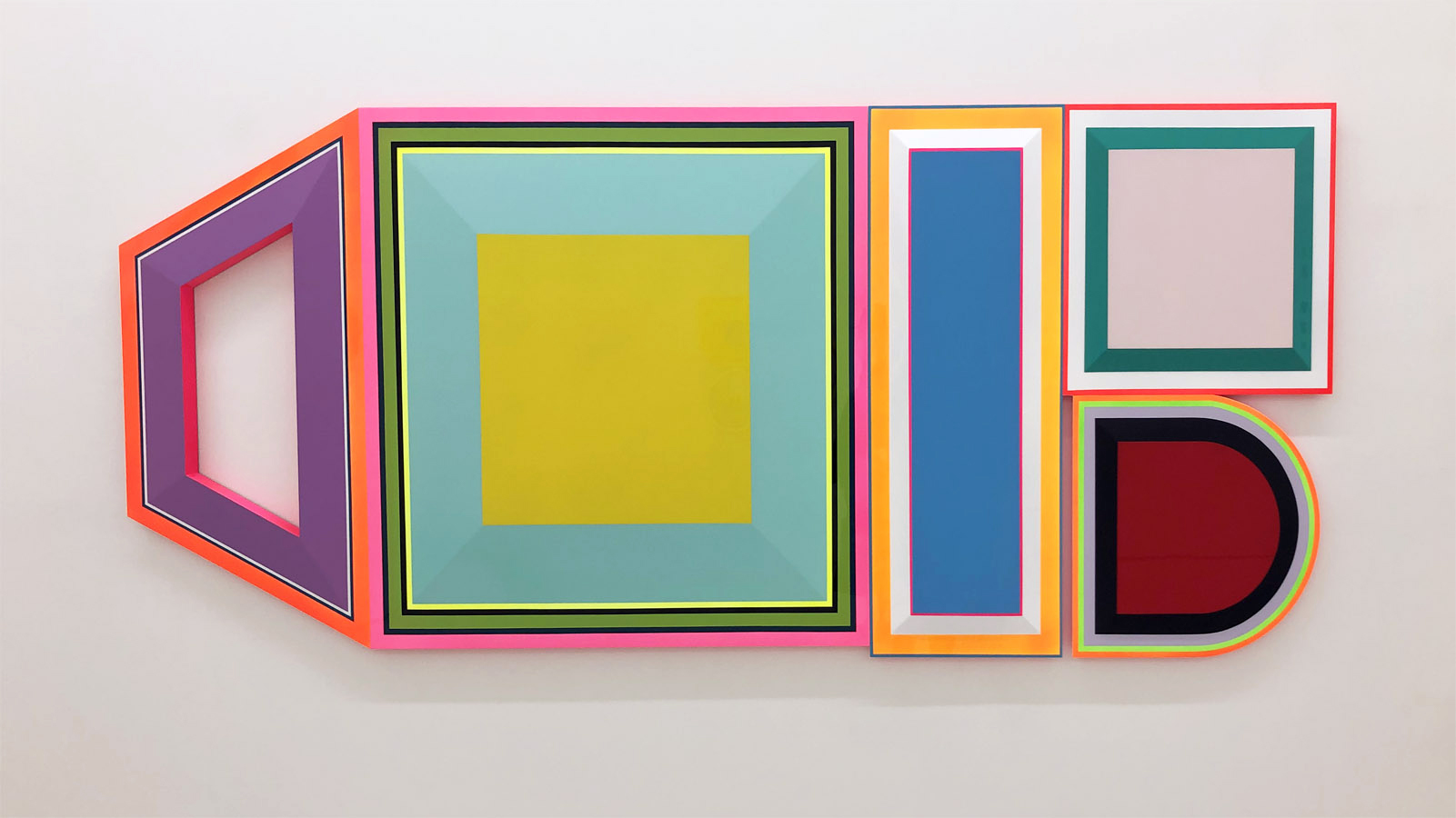

Allie McGhee, Long Look, Acrylic and enamel on vinyl on wood. 2021

Right when you think these folded and crushed colorful objects art are the beneficiaries of a life’s work and might be his last body of new work, he comes back with new flatwork on the wall, like the painting, Long Look, an acrylic and enamel paint on vinyl attached to wood. Is he looking through a microscope or a telescope? Or is he reading The Elegant Universe by Brian Greene about how artists look to science for inspiration? From the Cranbrook publication, McGhee writes, “I will see the Science section of The New York Times where there will be a photograph that is almost identical to something I painted years ago, like a picture from the Hubble telescope.”

There is something to be said about McGhee’s longevity with respect to being able to continue his process and reap the success of this later work. He is still exploring his evolutionary process, a painter of extraordinary ability who continues to contribute to the art record of Western civilization.

Allie McGhee exhibits a Retrospective, Banana Moon Horn, at Cranbrook Art Museum, through February 13, 2022.