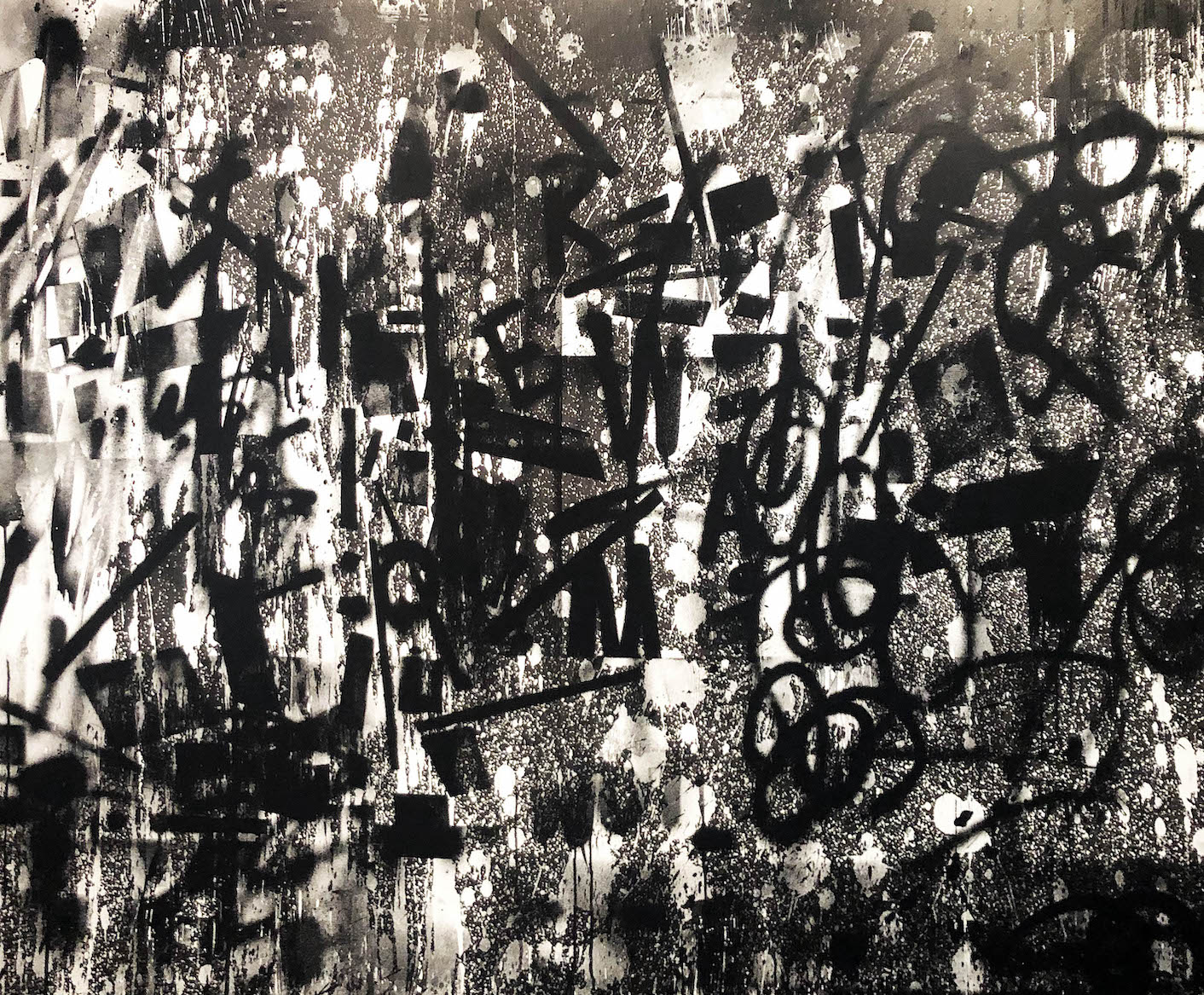

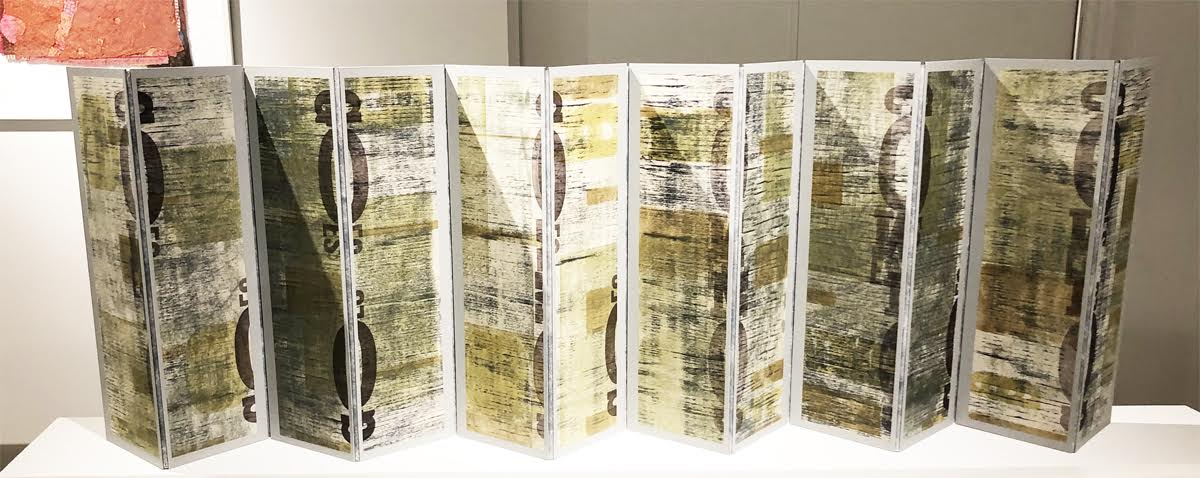

An installation view of Scott Hocking: Detroit Stories at the Cranbrook Art Museum. Detroit Stories is up through March 19, 2023. Image courtesy of Cranbrook Art Museum

There was a time, not so long ago, when most suburbanites and even some Detroiters regarded our grand, dilapidated city as an embarrassment. It would take youngsters just out of college in the early 2000s, dazzled by the postwar-Berlin landscape and surfeit of abandoned buildings to explore, to start to write a different narrative that didn’t run away from the city’s blemishes, but celebrated the beauty to be found within our fabulous ruins.

Scott Hocking, a 40something working-class kid from Redford Township, was in the forefront of that cultural vanguard two decades back, and his early forays caught the attention of a nation accustomed to ignoring Detroit. Luckily for those unfamiliar with his work and those who love it alike, the Cranbrook Art Museum has just opened his first career retrospective, Scott Hocking: Detroit Stories, up through March 19, 2023.

After getting his degree at the College for Creative Studies, Hocking established himself as one Detroit’s most articulate storytellers, creating work that reminded the world that the Motor City, for all its problems, is a mythic place deeply rooted in the American consciousness.

Starting in 2008, Hocking – impoverished like many students after graduation – began working with that great Detroit resource, found objects, out of sheer necessity. They were about all he could afford. But unlike the gifted Cass Corridor artists from the 1970s and 80s, who plowed the same field, Hocking wasn’t just picking up junk and creating artful collage or 3-D pastiche. His ambitions were epic in scale, and it quickly became clear his was a unique voice in a city increasingly crowded with interesting artists.

Scott Hocking, Ziggurat—East, Summer, 2008, installation view Fisher Body Plant 21, Detroit. Photo Courtesy of Scott Hocking and David Klein Gallery, Detroit.

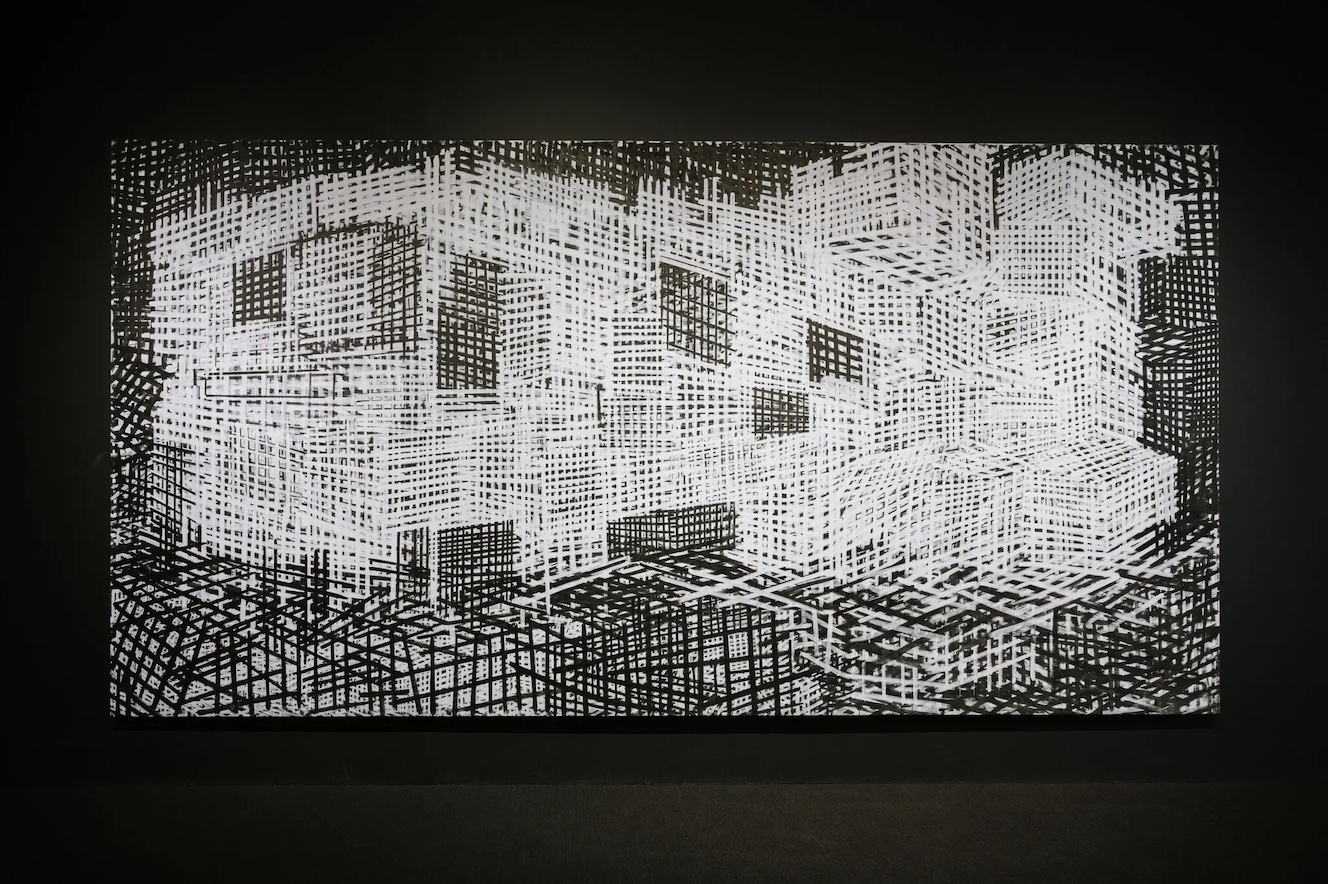

Hocking’s first grand conceit lit up the art world like a meteor — and vanished almost as quickly. Collecting some 6,201 wooden “bricks” that paved the concrete floors of Fisher Body Plant 21, a crumbling auto factory near the east-side tangle of railroad tracks known as Milwaukee Junction, Hocking built, block by repetitive block, a majestic Ziggurat or stepped pyramid. Set in the dead center of a vast, rubble-strewn factory floor and framed by two rows of industrial “martini columns,” the massive structure looked, for all the world, like an artifact from a lost civilization. For pure sculptural drama, Ziggurat was unbeatable – mysterious and jaw-dropping all at the same time.

“I always try to explain the beauty I see in Detroit,” Hocking’s said, and it amounts to a sort of professional ethic. And indeed, his creations go a long ways toward accomplishing just that. For its part, Ziggurat quickly got national exposure. A photographer, Sean Hemmerle, rounded a corner while exploring the city’s industrial infrastructure and happened upon the monument unawares. In an interview with The Detroit News, he confessed it knocked him right off his feet. The picture he produced would end up running across a full page and a half in Time magazine as part of an essay on Detroit.

Unfortunately, Ziggurat had a short shelf life. In a development completely unrelated to the sculpture, the EPA bulldozed all the floors in Fisher Body Plant 21 to clear out toxic debris – including Hocking’s sober stepped pyramid. But it hardly matters. Also a talented photographer, he documents all his constructions so they live on long after they’ve degraded or disappeared.

It’s also worth noting, whether intentional or not, that Ziggurat works superbly at the symbolic level. Had Hocking erected a tombstone in a dead auto factory, it’d be a gesture both banal and trite. But a ziggurat, like the pyramids, is a funerary object — even if that’s not our first association upon seeing it. It’s the oblique nature of the reference that gave the doomed structure its pathos.

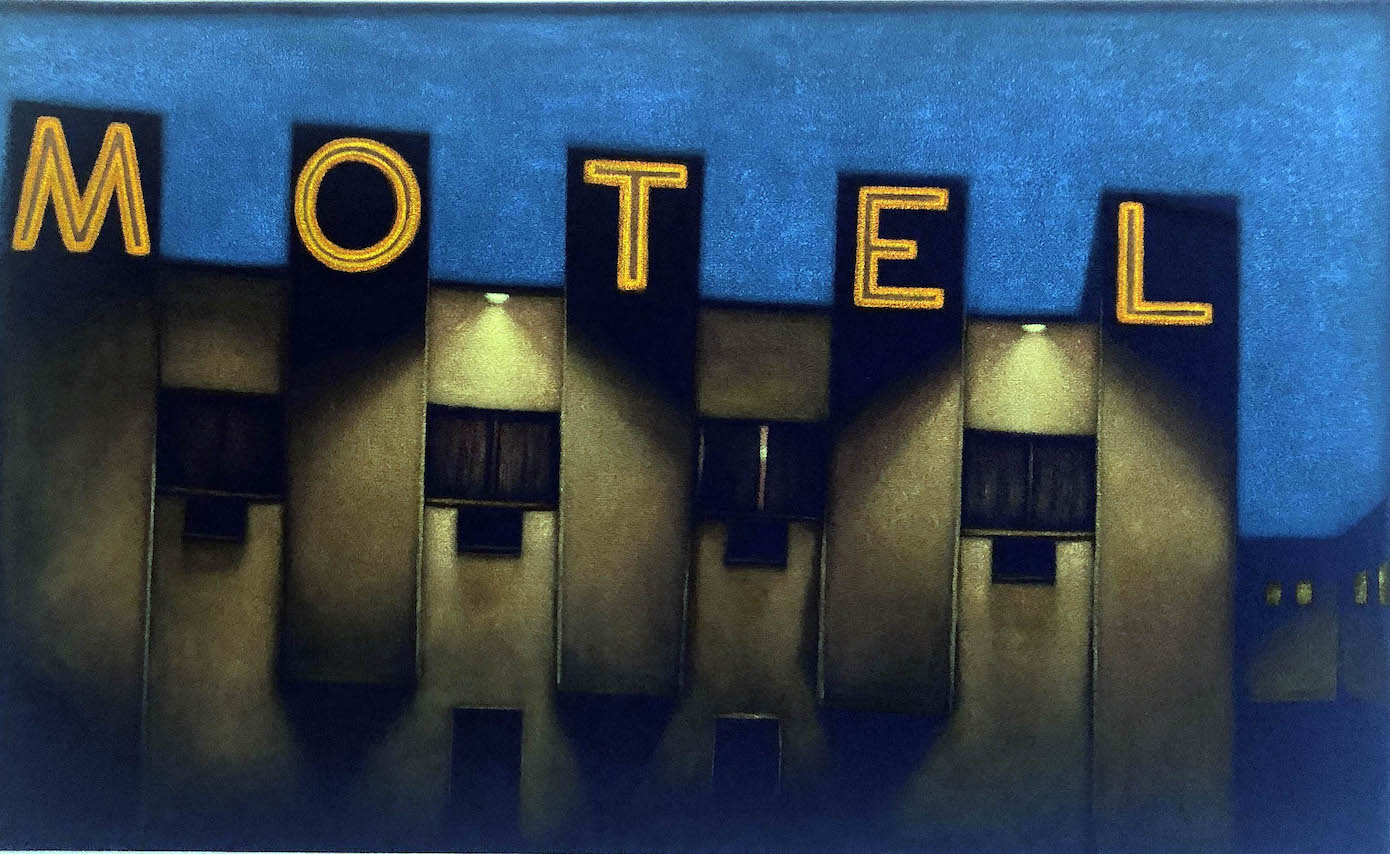

It has to be said that Hocking’s a veritable artistic polymath, with work ranging from the large-scale sculptures to installations to the haunting series, Detroit Nights, where he documents the dark city using available light. In the words of the show’s short introductory essay, Hocking – part archeologist and archivist – “[uncovers] layers of history, meaning and memory, with a historian’s sense of discovery and a writer’s craft of storytelling.”

Word to the wise: don’t miss his series of portraits of boats abandoned on Detroit streets.

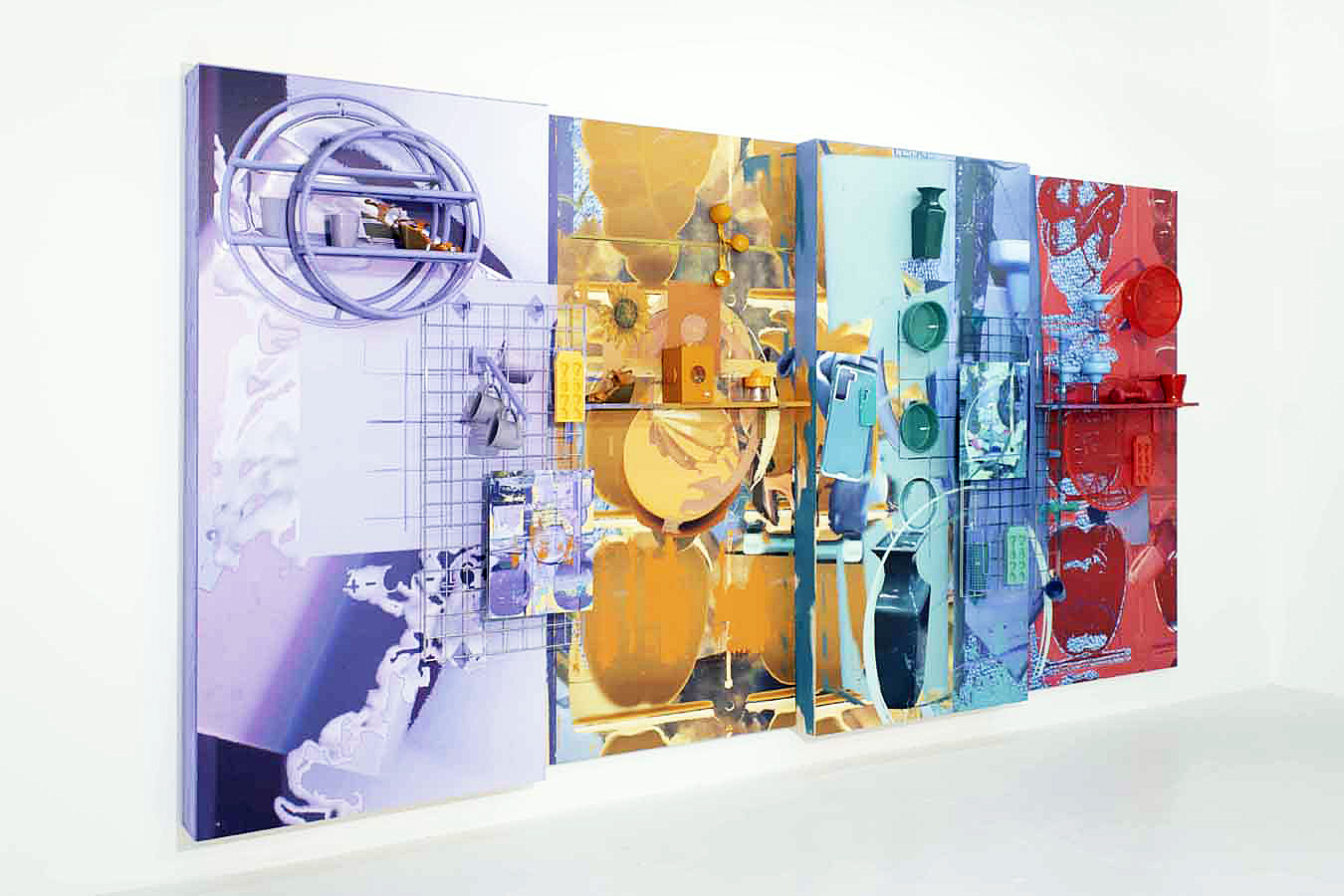

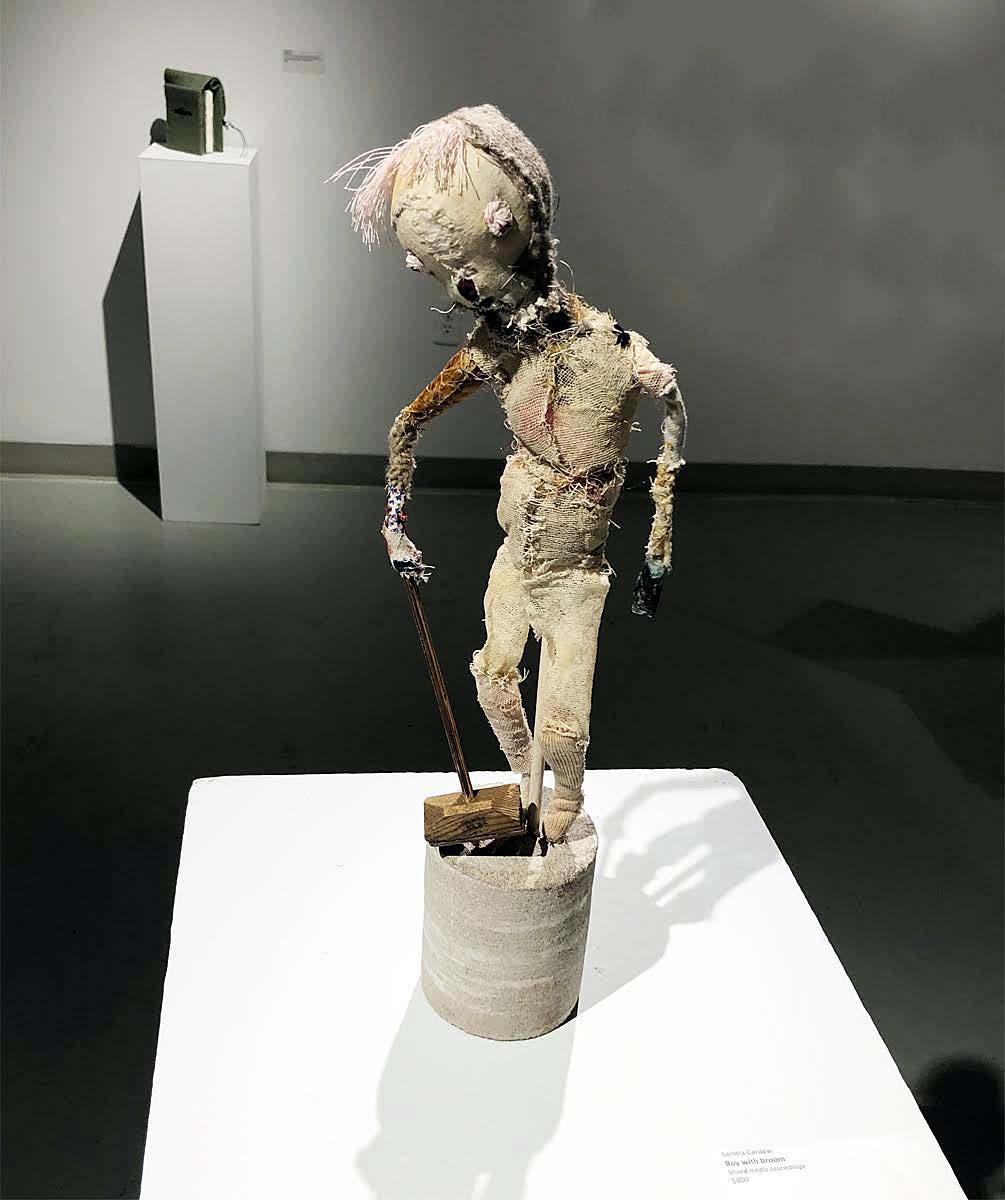

Scott Hocking, The Secrets of Nature, 2012 / 2014 / 2022, Fiberglas, wood paint, metal, concrete, various found objects, Courtesy of and David Klein Gallery, photo by deo Owensby.

One of the more striking assemblages on display, both funny and daunting, is the wall-sized Secrets of Nature. Here Hocking utilizes figurative artifacts, human and animal alike, found at what he calls “tourist traps and roadside attractions” – in particular, a clutch of Bible characters from the former Good Shepherd Scenic Gardens up north in Mancelona. The installation looms high above the viewer with dozens of saints and sinners peering down at you. The work’s got a weird depth. In the words of the accompanying label, Secrets focuses on “creation and destruction mythologies … and ancient prehistoric wisdom.”

Scott Hocking with The Egg and the MCTS, 2012, Photo Scott Hocking; Courtesy the artist and David Klein Gallery.

Another of Hocking’s astonishing, large sculptures was The Egg in Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, the towering wreck on Michigan Avenue now being renovated by the Ford Motor Co. into high-tech office space — one of the most recognizable symbols of Detroit’s decline.

Using shattered pieces of marble that had cracked off the walls along one of the upper-story hallways after decades of freeze and thaw, Hocking painstakingly assembled thousands of shards to create a symmetrical ovoid sculpture that’s easily nine feet tall. The design has an almost Japanese aesthetic in its use of irregular, jagged elements — albeit all the same thickness – to produce something elegantly and breathtakingly symmetrical.

Workers doing asbestos removal before Ford acquired the depot helpfully suggested to Hocking that the egg’s weight might be too great for the floor. So they built a structural support system right below to prevent collapse.

The Egg reflects Hocking’s interest in geometric shapes, but as with Ziggurat, you can read something more into the design – in this case, birth and renewal rather than death.

Of course, this being Detroit, making art out of the city’s desolation exposes you to the charge of “ruin porn,” the cheap shot leveled most frequently at outsiders who can’t refrain from taking pictures of our astonishing dilapidation – like the French photographers and authors Romain Meffre and Yves Marchand, whose 2010 “The Ruins of Detroit” scandalized Michiganders but dazzled the world.

Cranbrook Art Museum Director Andrew Satake Blauvelt, who curated the show, isn’t buying the allegation. “In this case, Scott is from Detroit,” he said, creating actual art in these buildings, not merely gaping. “It’s not just depressing pictures that will go in a magazine,” Blauvelt said. He points out that College for Creative Studies Prof. Michael Stone-Richards, who wrote an essay for the exhibition catalog, “also references the idea of ruins,” noting the fascination has a long history – indeed, going back to at least the 17th century, when Germans of means started traveling to Italy in search of the ancient and profound. “We go to Rome to venerate the ruins from past centuries,” Blauvelt said, because like Detroit, “they tell a story.”

Scott Hocking, Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark) AKA The Barnboat #0721, 2016, installation view, Port Austin, Michigan. Photo Courtesy of Scott Hocking and David Klein Gallery, Detroit.

Not all Hocking’s remarkable constructions are in the Motor City. Indeed, he’s been invited to create work around the world. But one of his most recent and compelling pieces is found in Michigan’s thumb outside Port Austin – where he created an enormous sculpture as part of the “barn art project” first launched by former Public Pool gallerist Jim Boyle along with Steve and Dorota Coy, two artists who go by the monicker Hygienic Dress League. The project’s turned four old barns scattered around the countryside into art objects both oddball and beautiful. (See especially architect Catie Newell’s “Secret Sky.”)

With permission from the owner, Hocking deconstructed an 1890s barn starting to slump and rebuilt it into an ark-like sculpture that hangs off several telephone poles — a fitting metaphor, many would say, for our imperiled times.

It’s often said that the arts have “saved” Detroit. And it’s indisputable that at the turn of the century, Detroit and the state of Michigan were fortunate in having a rich crop of talent who made the Motor City their subject long before it became chic – among them Taurus Burns, Clinton Snider, Corine Vermeulen and Andrew Moore. While Hocking’s work is the most peculiar and original of the bunch, they’ve all helped Michiganders and the world at large see Detroit in a fresh light.

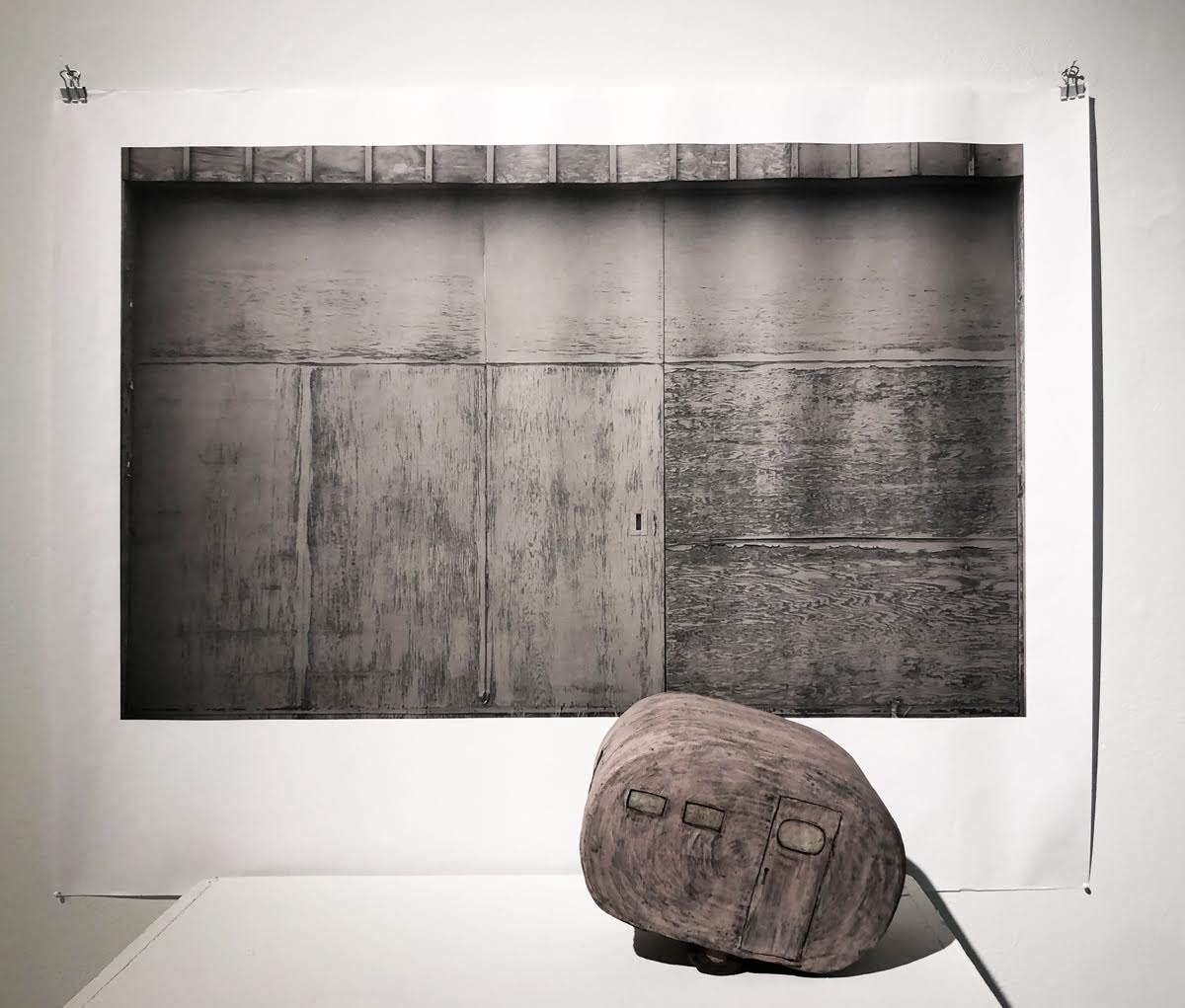

Scott Hocking and Clinton Snider, Relics, 2001. Photo by deo Owensby.

Scott Hocking: Detroit Stories at the Cranbrook Art Museum is up through March 19, 2023.