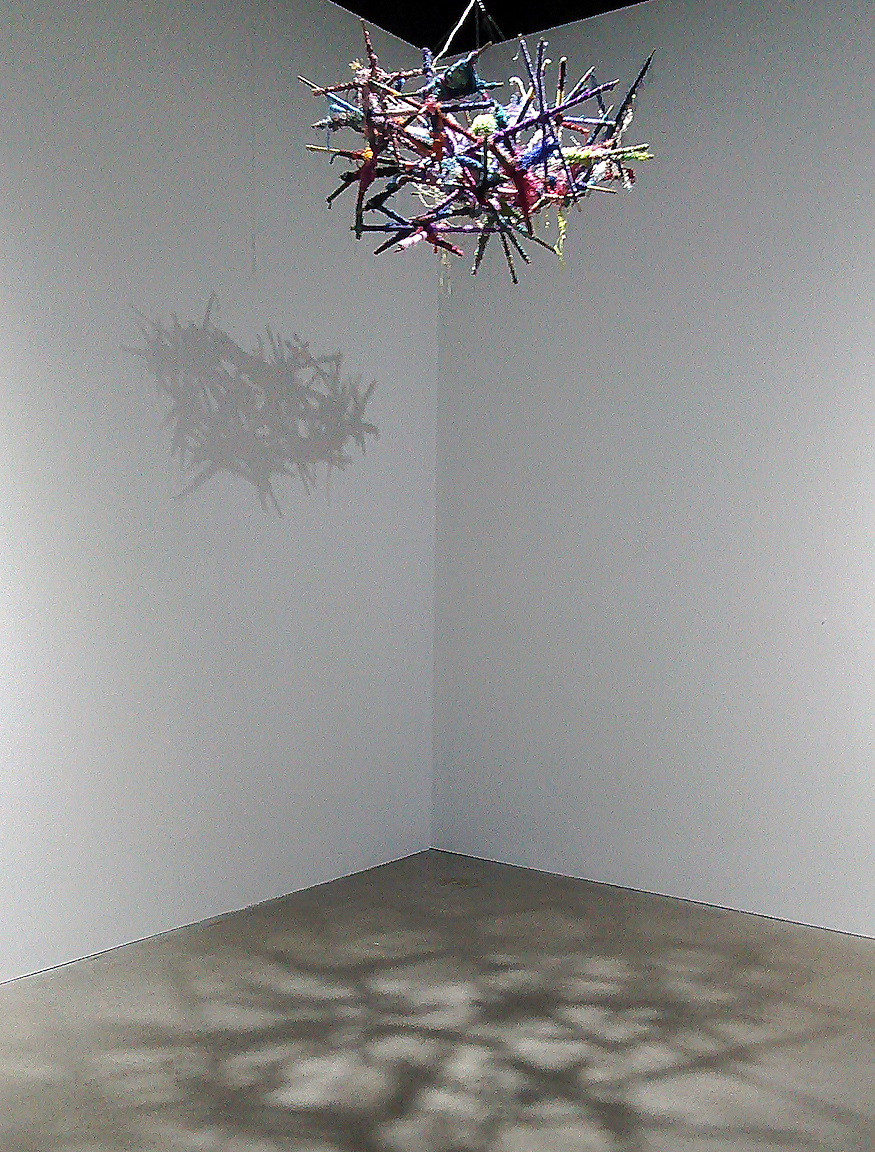

W.C. Bevan, “Contrast” partial installation view, All images – Ryan Standfest

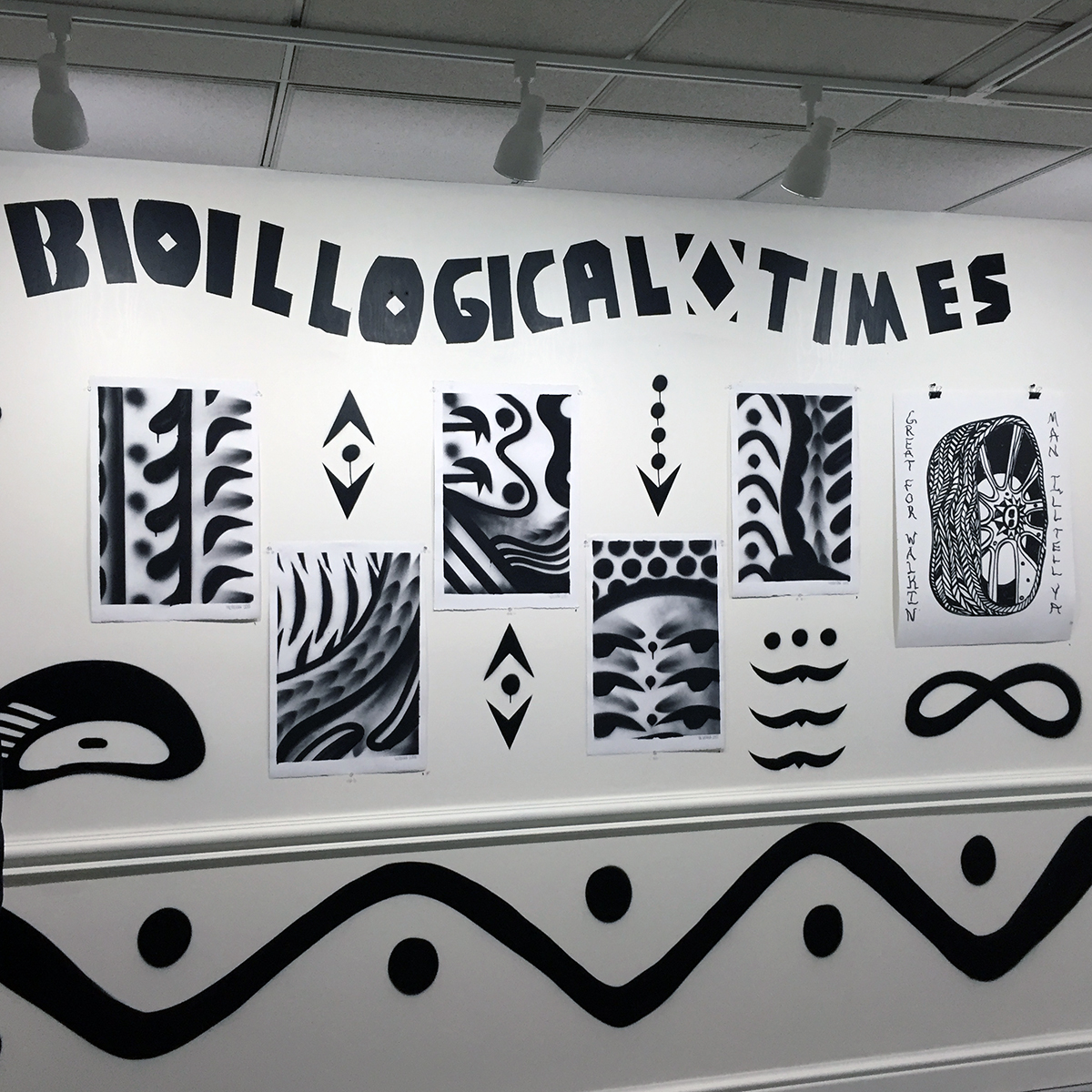

Entering into the space of the new Greenroom Gallery for its second exhibition, “Contrast”, a collection of 24 black and white painted, printed and drawn works by W.C. Bevan, muralist, graffiti artist, printmaker and painter, one comes upon a seamless environment in which wall surface and the individual works presented on it, augment one another to resemble a brightly-lit cave covered with symbols and representations both prehistoric and futurist, of our time and outside of our time, vague and precise. There is a timeless music issuing forth from this chamber.

BLACK & WHITE

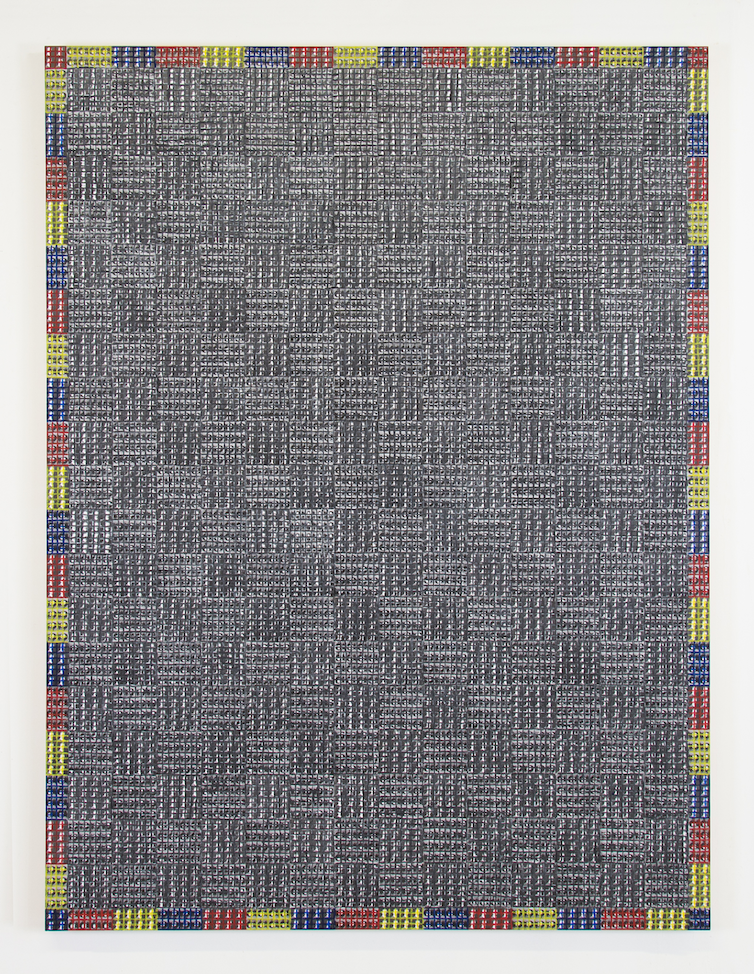

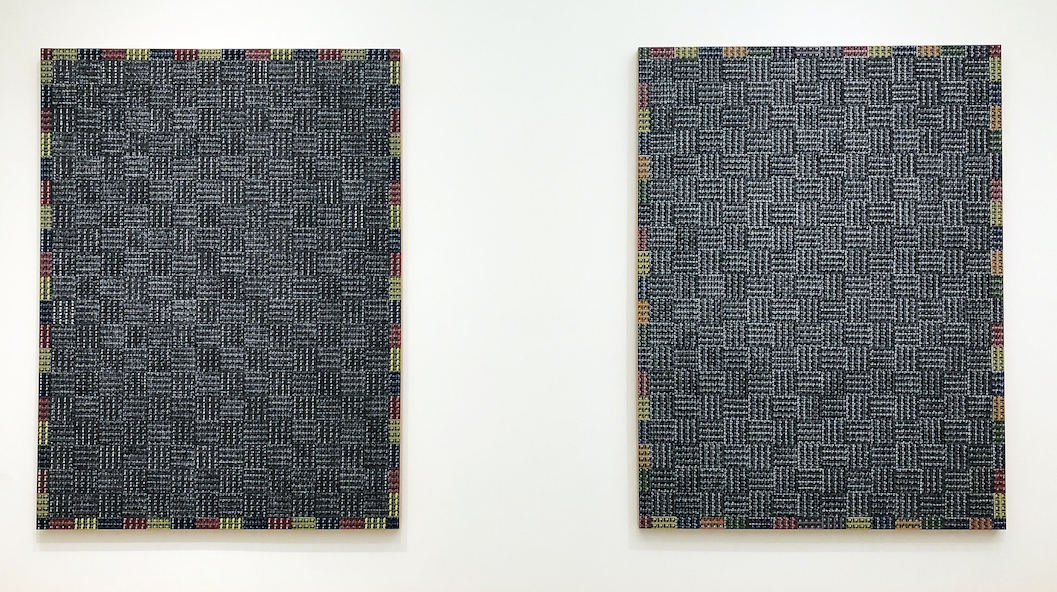

W.C. Bevan states that black and white is his “preferred mode of transport.” It’s usage suggest basic black ink on white paper, the foundation of a D.I.Y. print aesthetic cultivated in an underground Punk culture of fast and cheap photocopied zines, handbills and posters. But economic necessity also gives way to meaningful form, as high contrast lends itself to the graphically impactful, the immediate read from whatever distance. Color can carry with it nuance, emotional shading, a reading that depends upon one’s preconceived connection to a color. Whereas the simple combination of black plus white has no hidden agenda up its sleeve.

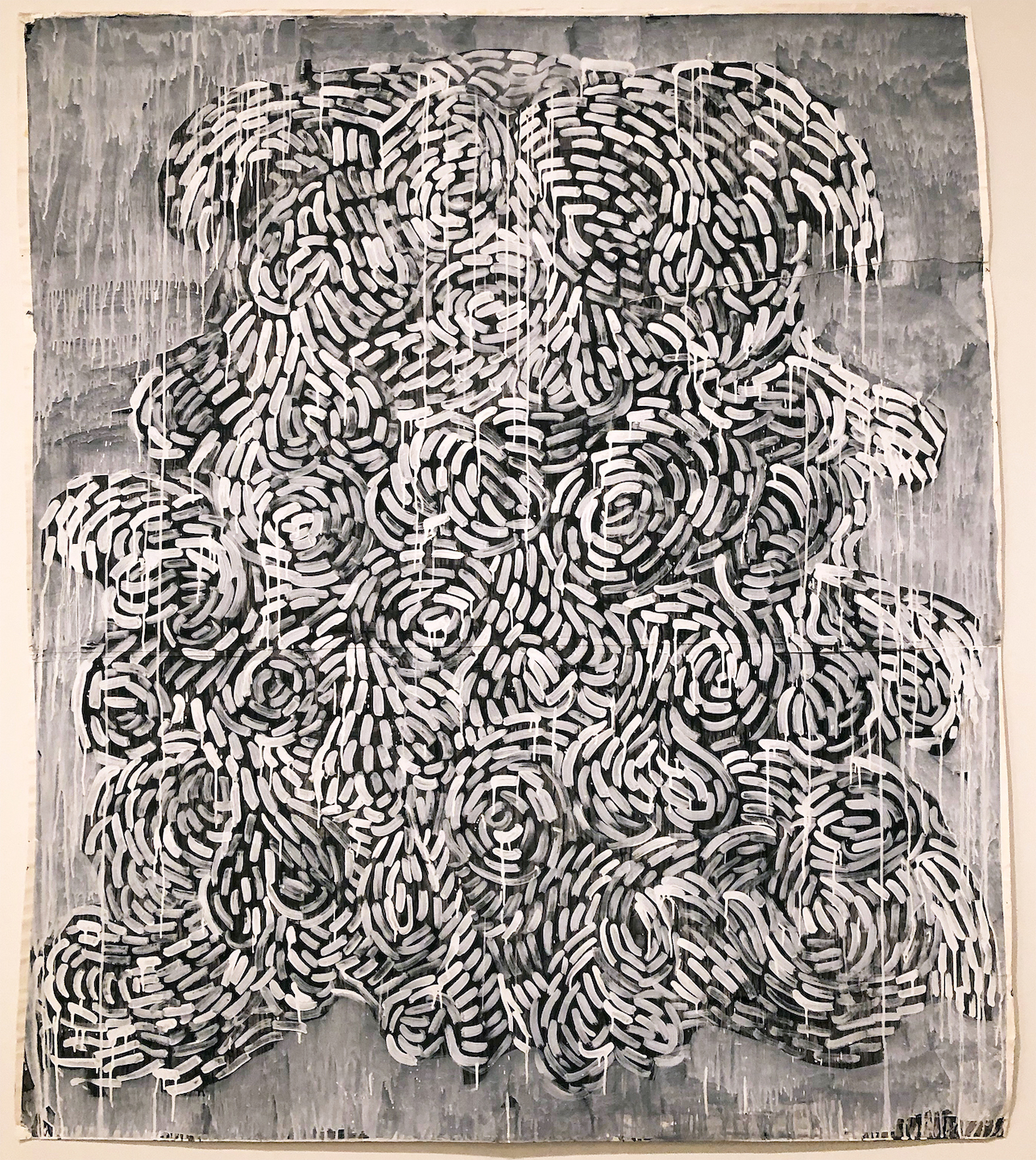

However, there is the presence of grey. When Bevan utilizes a can of black spray paint to adorn the walls of his exhibition space, he makes skilled use of the resulting overspray as a gradient, softening the image. He likens this to the mis-registration of a printed image, in which a layer of color slips outside of its intended target, accidentally lending further dimension. Indeed, there are also an abundant number of drips allowed to remain, unedited, that keep the space active, reminding the viewer of the performance required to manufacture marks.

Bevan’s methodology is a balancing act between exerting control and embracing chance. Upon an initial encounter with a space, a wall, a surface, a scenario must be devised in reaction to circumstance. Visual anchors are established using large scale icons. Connective threads between these anchors take the form of repeated visual motifs, adornments that form a flowing space to be read. Entering the Greenroom Gallery space, flashes of prehistoric cave art abound. As with the Paeolithic paintings found in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave, Bevan’s spray-painted marks respond to the various openings, contours and edges of the wall’s surface, making use of spatial shifts as an opportunity to animate his shapes and lines.

W.C. Bevan, “Contrast” installation detail, acrylic spray paint on wall, 2018

These adornments comprise a lexicon, assembled from typographic symbols. Bevan’s walls have a strong hieroglyphic character, suggesting black and white pictographic texts. It is no surprise then, that his practice of black and white mural painting began with the 2015 project “True Meridian,” which adorns a large wall on the former Eastern Market location of the letterpress shop Salt & Cedar, on the East Fisher Service Drive. Proprietor Megan O’Connell and Bevan had envisioned the mural as a black and white “cathedral of type” in response to the idea of letterpress. The resulting image retained its ecclesiastical architectonics, but letterforms gave way to a dizzying pattern of abbreviated characters.

W.C. Bevan, “Contrast” installation detail, acrylic spray paint on wall, 2018

Growing up in Cleveland, surrounded by examples of opulent turn of the 20thcentury architecture, much of Bevan’s wall-marking practice has been defined by a relationship with architectural ornamentation; the decorative repetitions that activate the façade of a building through the rhythmic accretion of detail. This visual language is on view in “Contrast.” The Classical ornamental device known as “egg and dart,” which consists of an egg-shaped object alternating with another element shaped like an arrow or a dart, is echoed in the spray-painted embellishments on Bevan’s walls.

W.C. Bevan, “Contrast” installation detail, acrylic spray paint on wall with “Untitled” drawings and “Tire Poem” print, 2018

TIRES

The “contrast” of the title is not just black and white, but also the organic and the inorganic. One prominent text adorning a wall states “BIOILLOGICAL TIMES” (a kind of subtitle to the show) as a reminder of the uneasy relationship between the natural and the industrial.

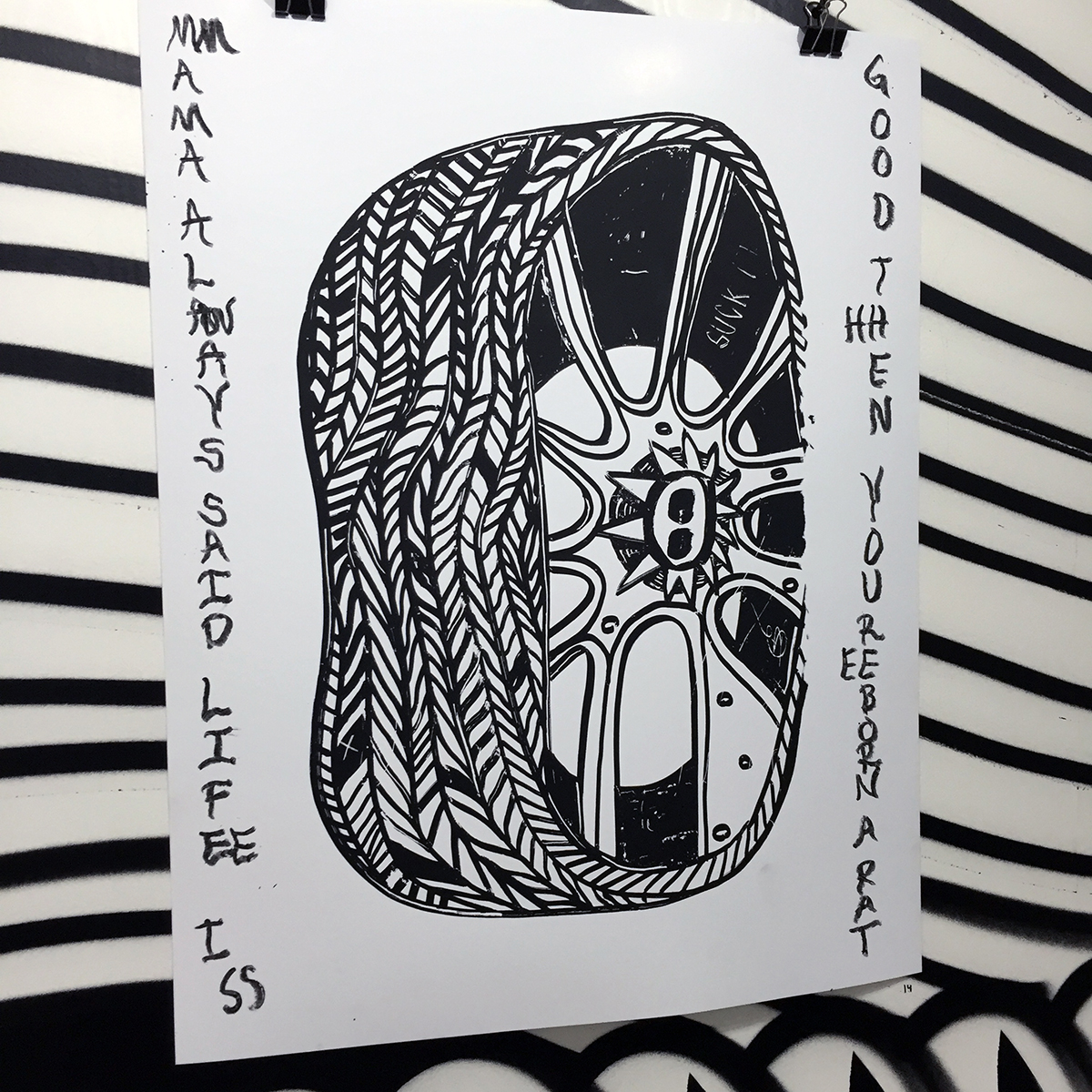

The recurring motif of the exhibition is the automobile tire. It appears in a series of oversized visual anchors, in a smaller series of screen prints with poems scrawled in black oilstick, as piles in smaller acrylic paintings on canvas, and deconstructed as tread marks that reframe and elaborate a new, more playful architecture within the exhibition space.

W.C. Bevan, “Tires”, acrylic on canvas, 22 x 17.5 inches, 2018

In the series of small acrylic paintings depicting tire piles, the subject becomes a surrogate for bodies—slumped, disposed of. Bevan speaks of the tire as a thing that has gone places, that has been worn down while carrying us places, therefore having a history itself. The very idea of the tread has multiple meanings: to walk along, to press down onto the ground, to crush or flatten. In “Contrast,” tires themselves have been crushed and flattened, having carried themselves too far. The piles he depicts morph into less recognizable heaps and mounds, as they go treadless. Throughout the exhibition space, there is an unraveling of the tire, a peeling away of the tread—unspooled to become architectural pattern.

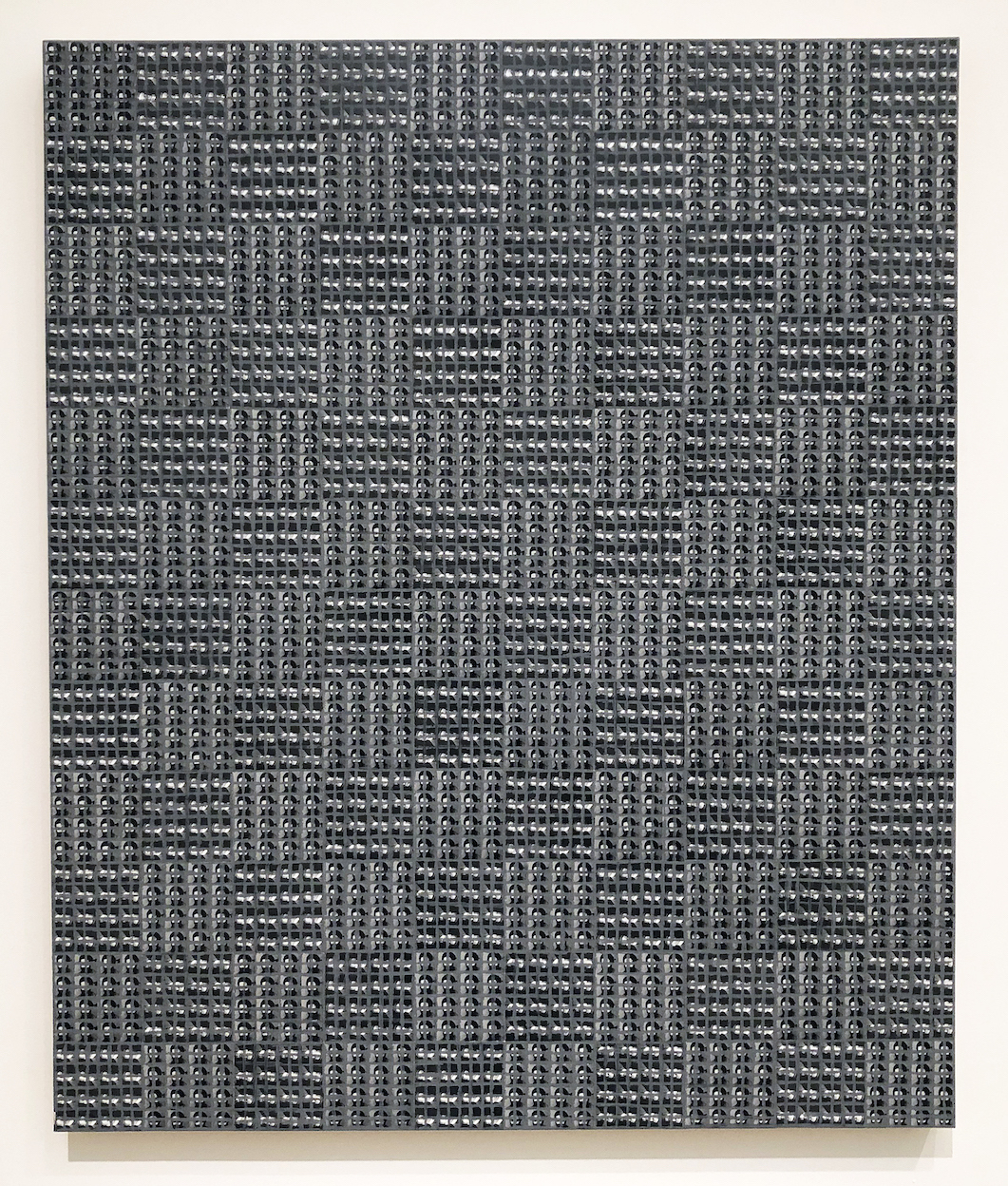

W.C. Bevan, “Wall Peeps”, acrylic on canvas, each 15.5 x 12.5 inches, 2018

Ultimately, the tire is not the subject. In fact, the tires are not just tires. For Bevan, the urban experience of the discarded tire, tossed into a field, piled, stacked, becomes an absurd totem. A deflated tragicomic sign of what has passed. Bevan’s tires are droopy, flaccid, out of shape. Having spent some time painting commercial signs populated by “hamburgers, liquor bottles and tires” for quick cash, Bevan has spoken of a fondness for hand-painted tire shop signage around the city of Detroit, that often represents the tire and or wheel as something misshapen. Unmoored by the refined craft of a trained artist, there is an clumsy earnestness to most of these signs with their straightforward deformation of what Bevan calls “the thing that keeps America moving.”

STREET

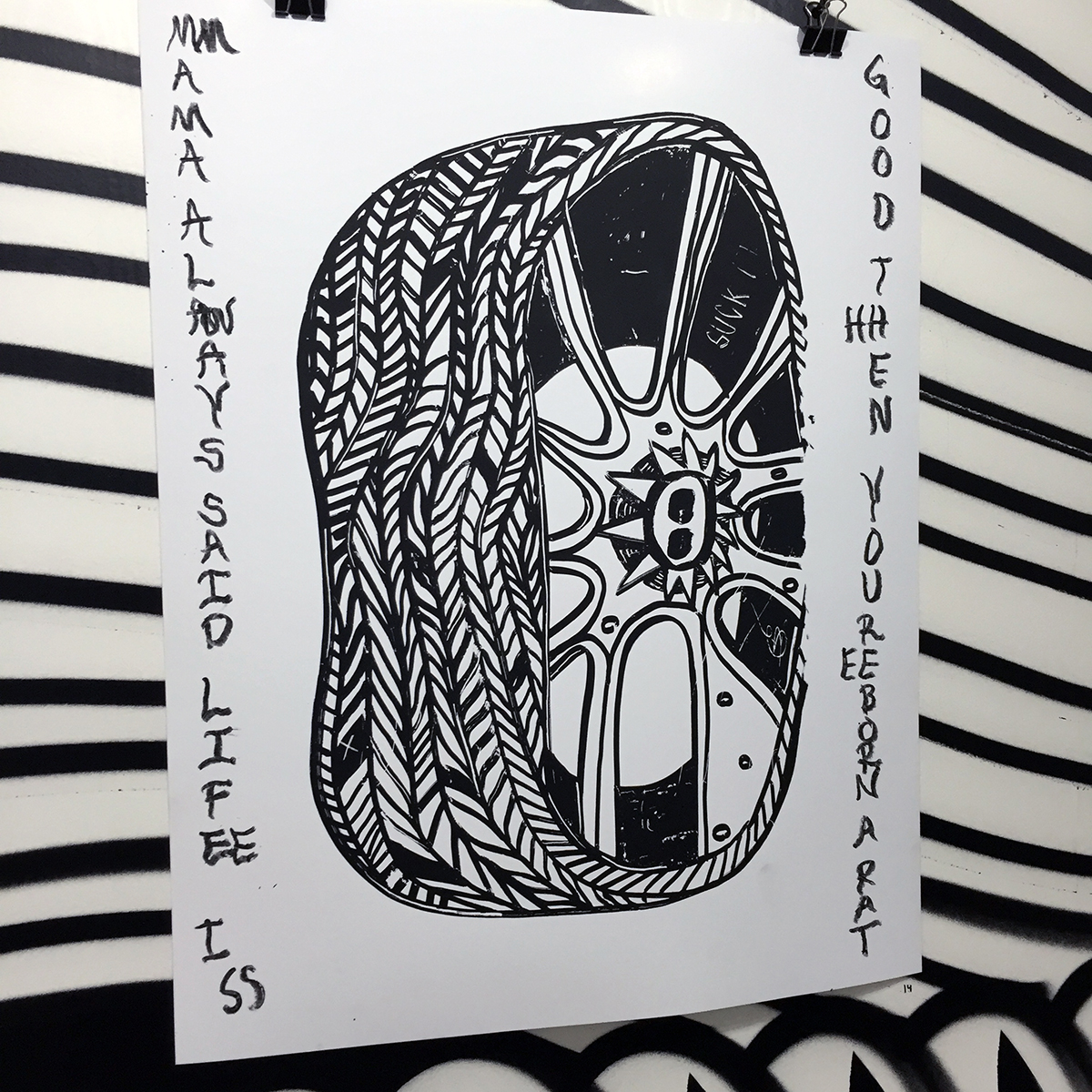

On screen printed works each titled “Tire Poem,” Bevan scrawls variant texts with a black oil stick, at the sides of each repeated, centrally printed tire image. The texts have a touch of the street to them, rough fragments drifting into the image nudging them toward something resembling a hand-painted sign:

LONG HISTORIC PIANO SONG

PIRATES MADE OF YOGA

GREAT FOR WALKIN’ MAN I’LL TELL YA

SUDAFED NAIL BED

MMAMA ALWAYS SAID LIFEE ISS GOOD THHEN YOUREEBORN A RAT

YOU’RE A PONYTAIL WOW

W.C. Bevan, “Tire Poem”, screen print with oil stick, 28 x 22 inches, 2018

The majority of the work in “Contrast” makes use of vernacular visual street language. In conversation, Bevan points out a series of paintings depicting tires by the artist Art Green, who was a member of the Chicago-based Hairy Who—a group of artists producing work in the late 1960s to early 1970s that was a potent mélange of high and low tendencies culled from comic books, Art Brut, commercial advertising and popular illustration, resulting in fragmented and highly fluid, often sexually-charged work that was a deliriously absurd response to the times it was made in. Similarly, Bevan’s work constructs a “Rustbelt Absurd” with its own pictorial elasticity, erasing notions of high and low with a language both refined and unrefined, and a practice that bridges the street and the studio with mural painting and graffiti, printmaking and painting.

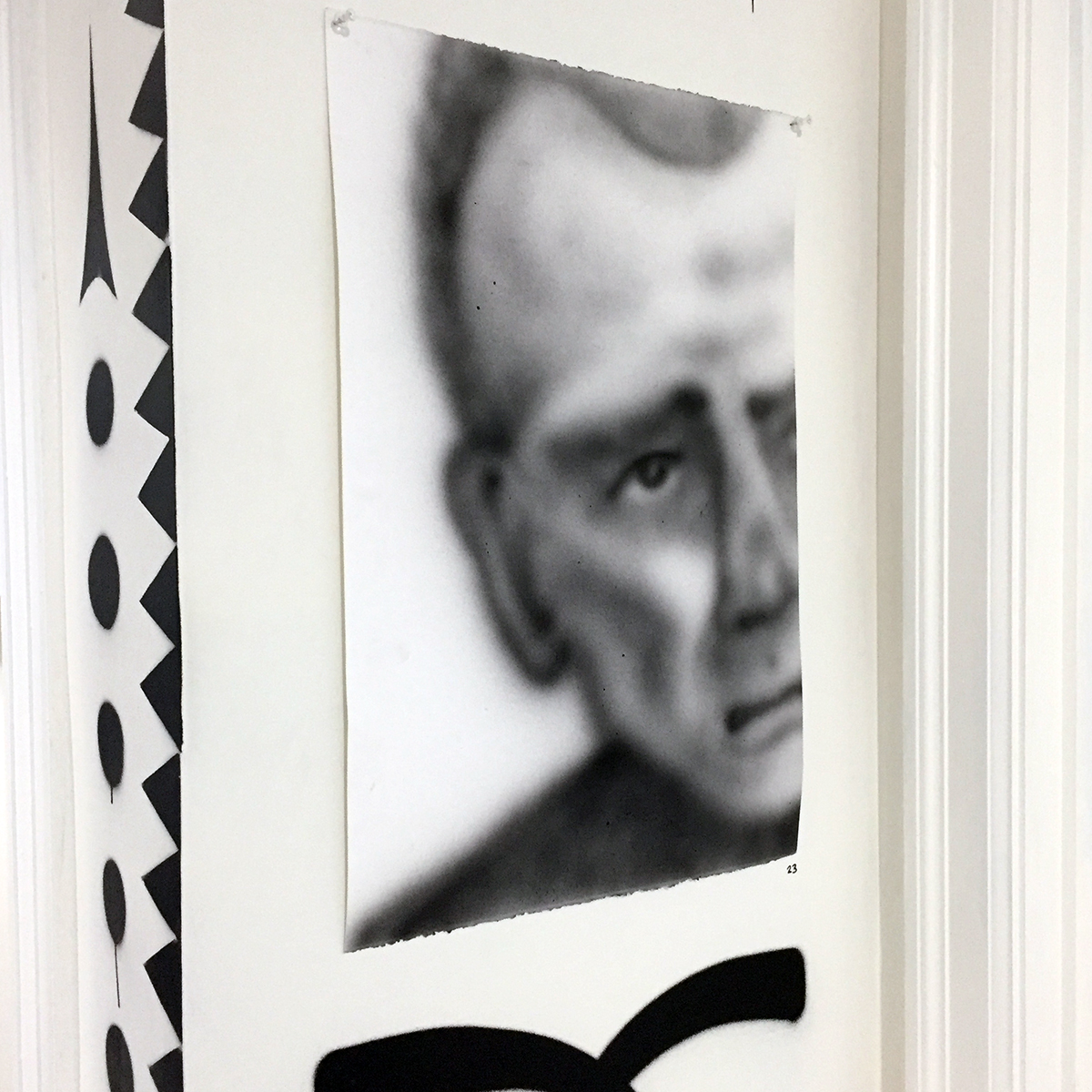

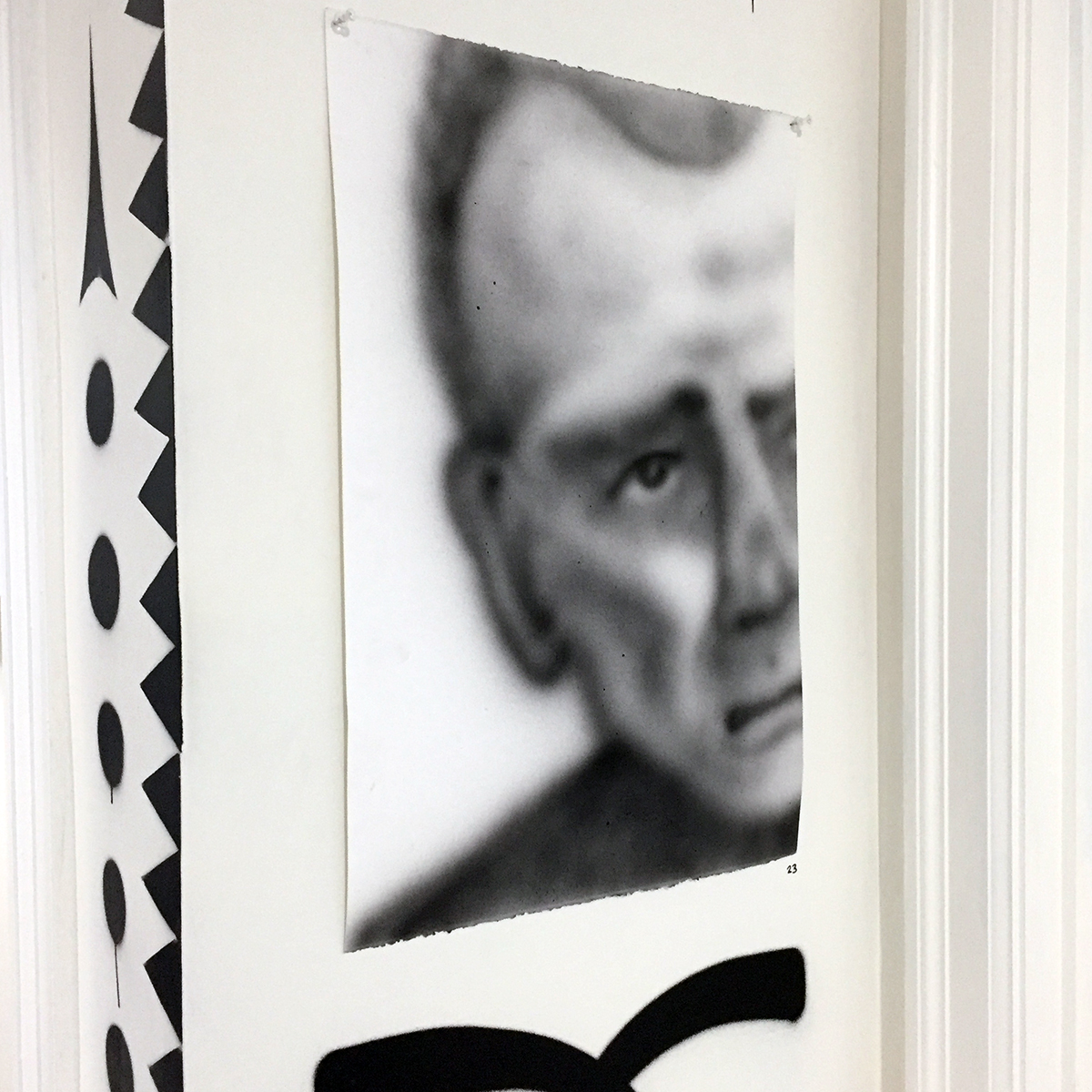

W.C. Bevan, “Hamtramck Memory Drawing”, acrylic on paper, 22.5 x 15 inches, 2018

There is a portrait, seemingly out of place in the exhibition, titled “Hamtramck Memory Drawing,” of a man, possibly of Eastern European extraction, partially cropped. Possibly working class. Possibly from the Poletown neighborhood Bevan has lived in since March of 2018. The drawing, executed with sprayed acrylic on paper, is a soft grey. It feels distant and contrasts with much of the hard-edged graphic work in the exhibition. In its quietness, it asserts itself as a reminder of the human dimension of Bevan’s work, the psychological lifeblood of a black and white Rustbelt vision, placing the everyday of the studio into the street, and vice versa, while summoning the abundant wall-painted symbols as dispatches from a landscape tread upon.

“Contrast: Black and White works by W.C. Bevan”

November 30, 2018-February 1, 2019

Greenroom Gallery Detroit

located within Emerson’s Haberdashery, 1234 Washington Blvd., Detroit, MI 48226

Gallery Hours: Tuesday-Saturday, 10-6pm

Closing reception on Feb. 1, 2019, 6-9pm