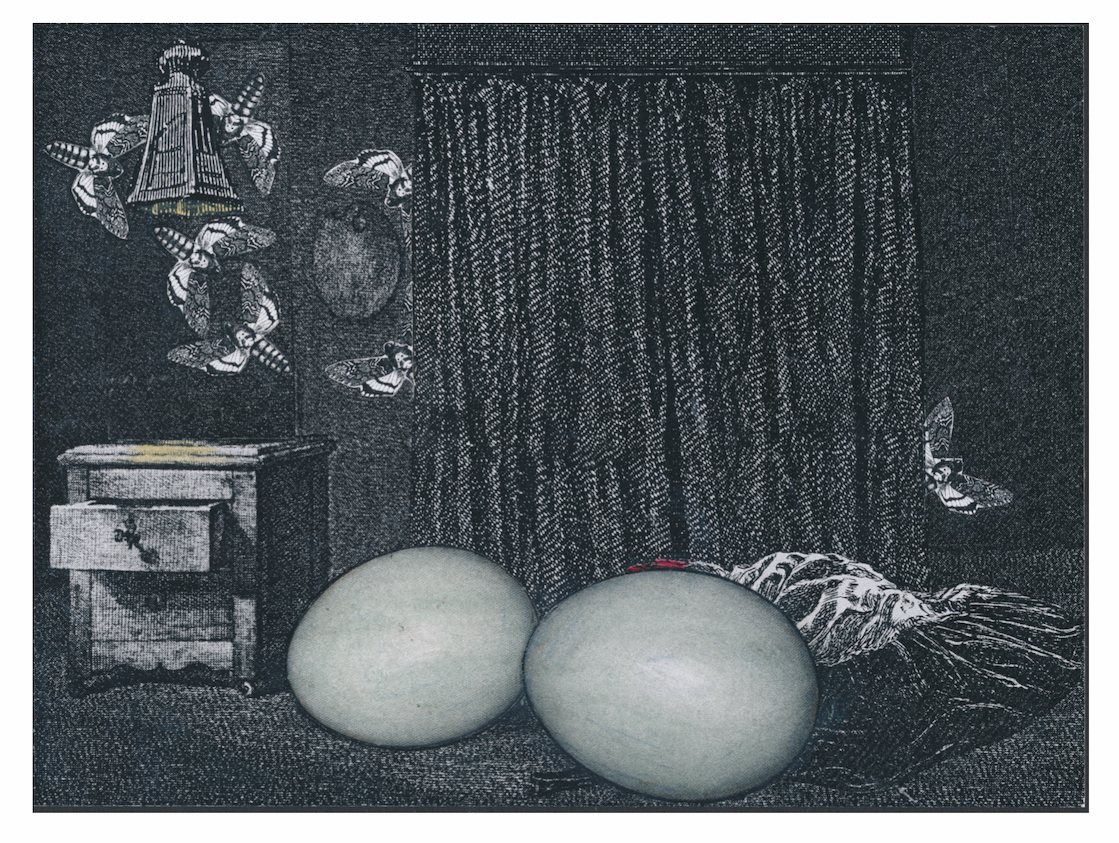

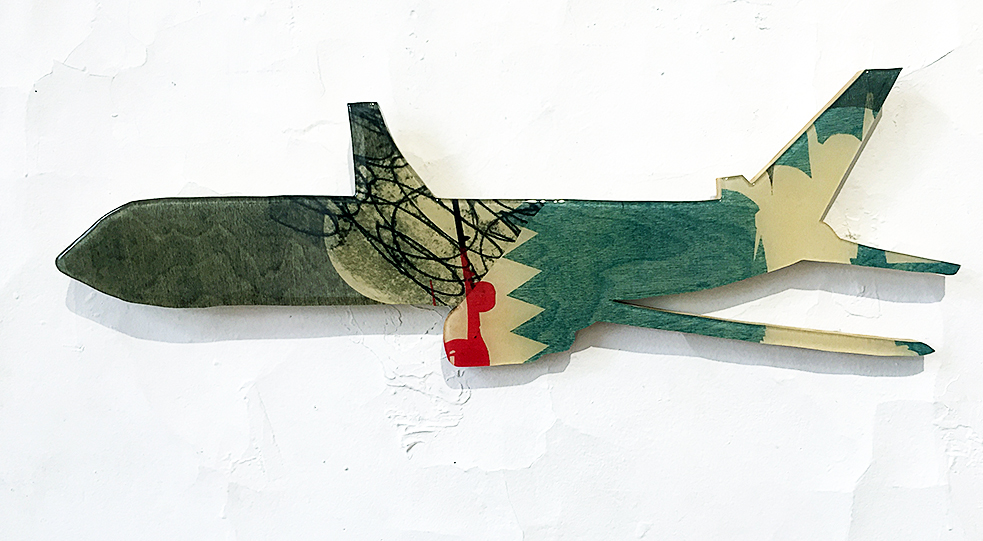

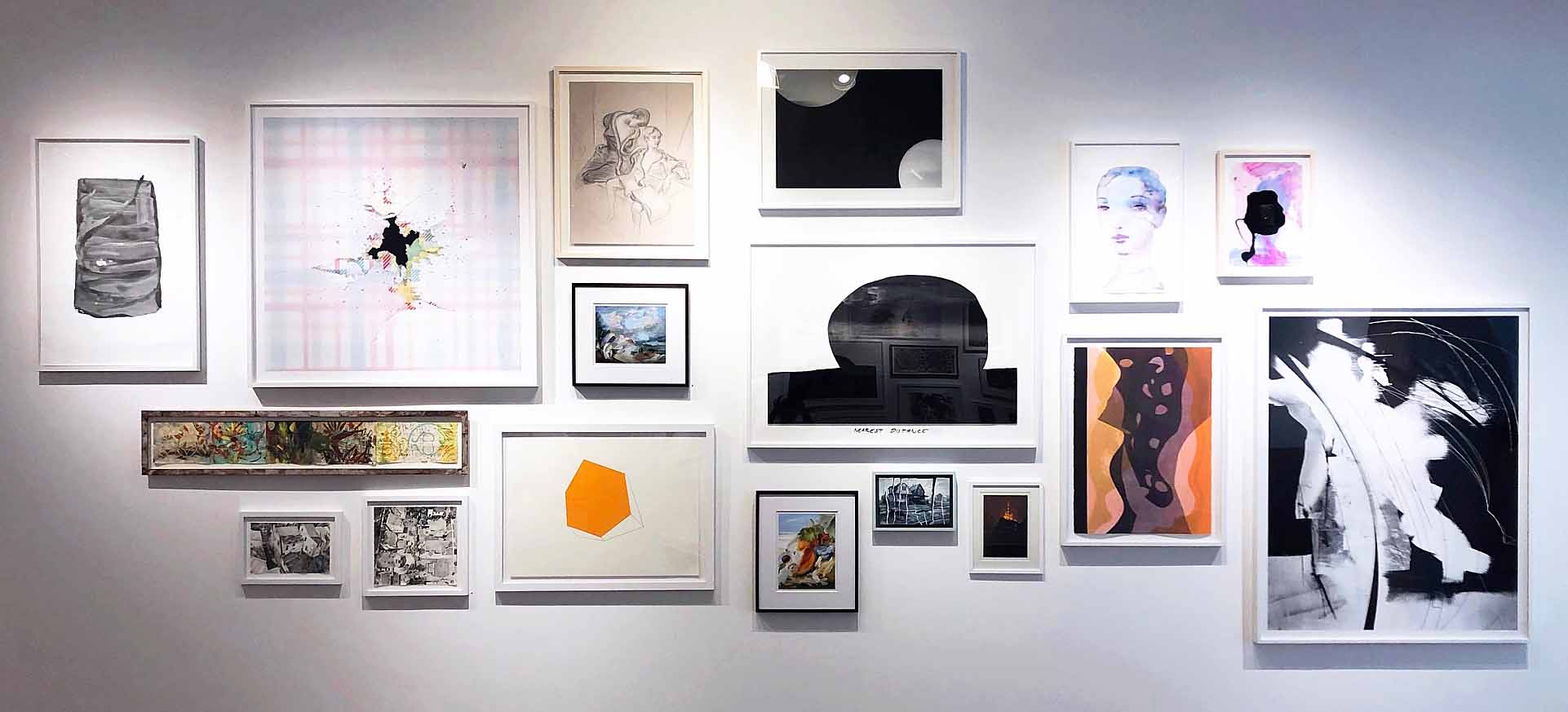

“SALON” Gallery 1 Installation View. All photos are courtesy of David Klein Gallery.

At the David Klein Gallery, Detroit, the exhibition “SALON” ambitiously presents 90 works by 39 artists across a range of media, with sundry formal intentions in diverse dimensions, all the while accomplishing the near impossible task of curating a ruminative viewing experience in which a spirited dialogue between each work translates into an expansive conversation with its audience. “SALON” summons and breathes new life into old models of art viewership and cultural discourse that once placed an emphasis on wide-eyed pluralistic wonder.

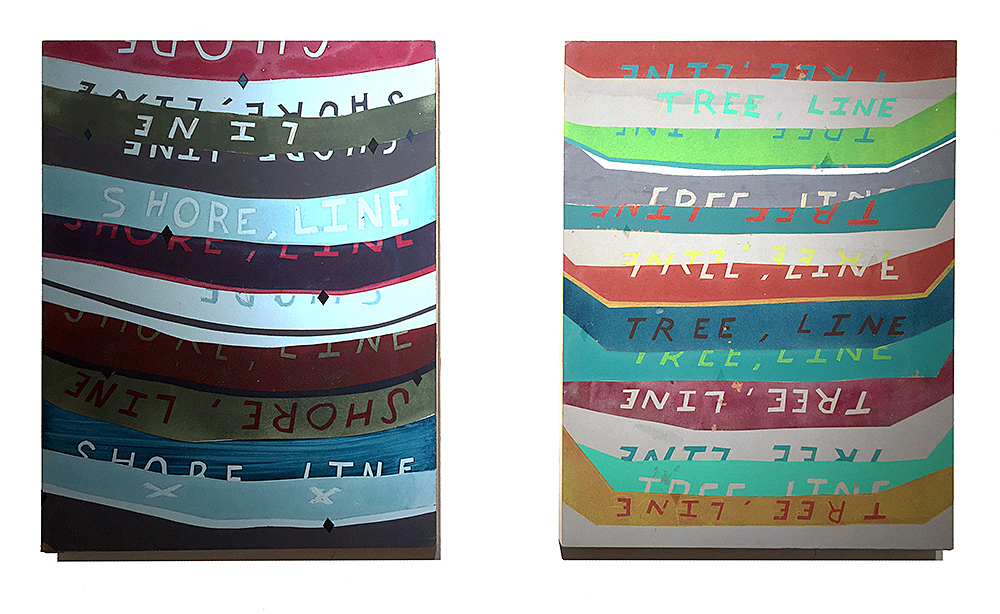

“SALON” Foyer Wall Installation.

The term salon originates as a social event that flourished during the Enlightenment. A crucial practice in “the age of conversation,” the salon collected persons of intellectual and cultural significance within the home of a well-to-do host to allow for an absorbing, investigative conversation on a wide-ranging set of issues. These were intended to be regularly recurring conversations around art, literature and politics to satisfy a hunger for knowledge while refining the tastes of all participants, mingled with a dose of amusement as egos politely debated for intellectual superiority. The salon also came to be identified with a series of academic art exhibitions beginning in 1667, at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Work chosen to be exhibited by a juried system, jostled for space in dense groupings that covered the wall from top to bottom. With the rise of public museums in the 18th century, a similar method of presentation was followed. Work that had once been displayed in private collections, often serving as the backdrop for salon conversations, and were ordered as closely grouped arrangements to juxtapose formal contrasts more immediately, was replicated in the new public displays.

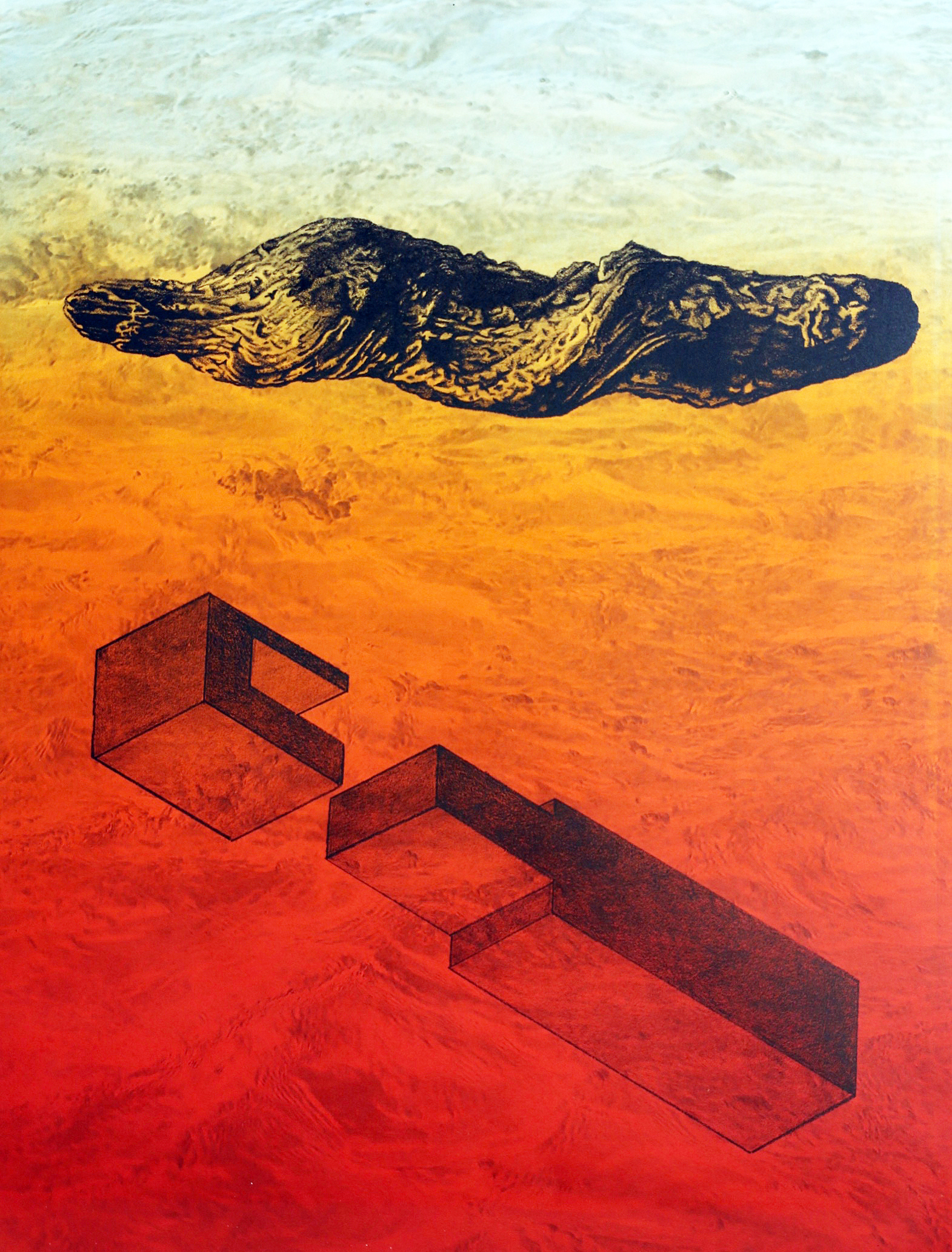

“SALON” Gallery 2 Installation View.

Crowded together to view a salon exhibition, the public was at times overwhelmed by the tightly clustered variety of works, but also in a state of awe and wonder, delving into vigorous conversation. With the advent of the “white cube” display methodology with neutral walls, controlled lighting and the spatial isolation of individual works of art inducing a hushed distance among viewing patrons, the salon approach was no longer the de facto system. The white cube environment, the earliest known iteration being an 1883 exhibition at London’s Fine Art Society by American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), was initially intended as an innovation to eradicate distraction, disconnecting art from the world and imposing more rigorous viewing criteria upon the viewer: there is only one way to see the artwork, and it is thus. Subsequently, what was innovative has now become conventional, with institutions and galleries continually questioning how to liberate the viewing of art from the impulse of Modernist constraint.

“SALON” Gallery 1 North Wall Installation.

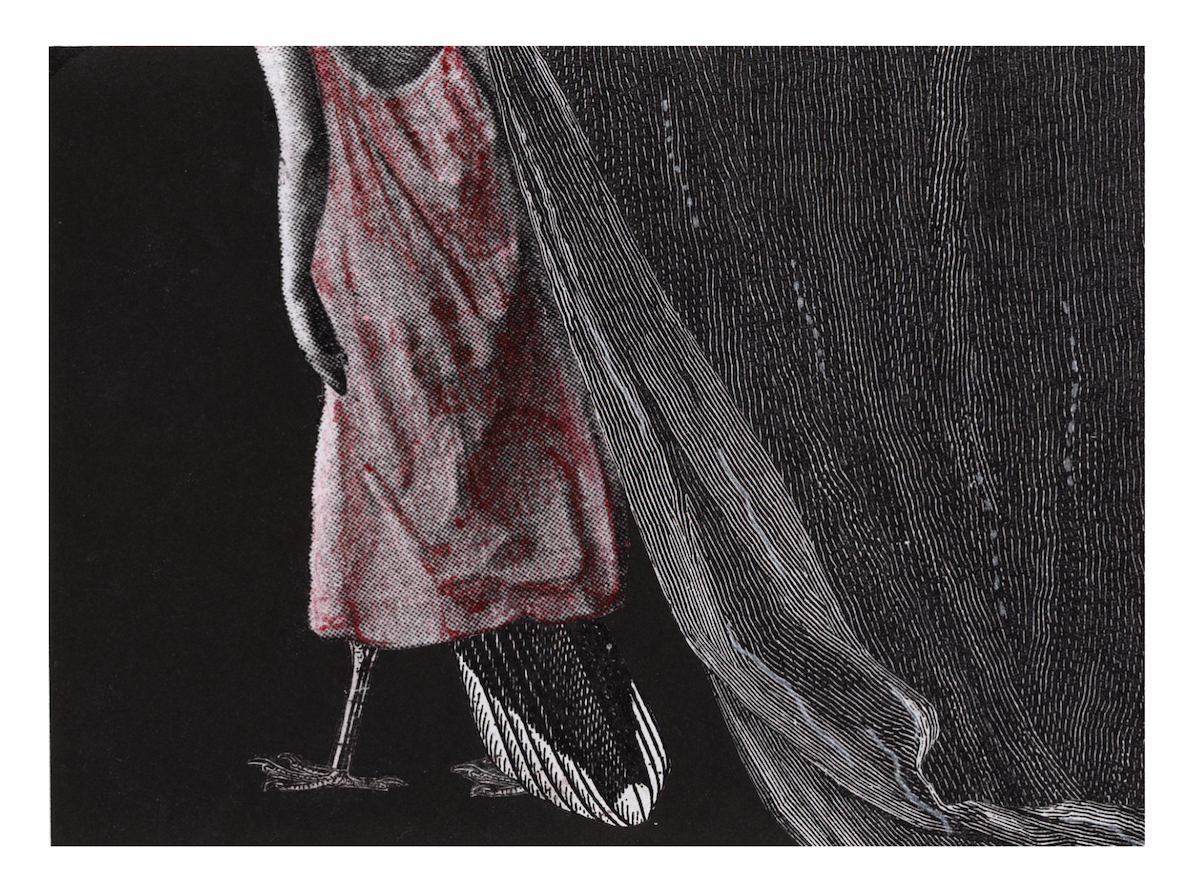

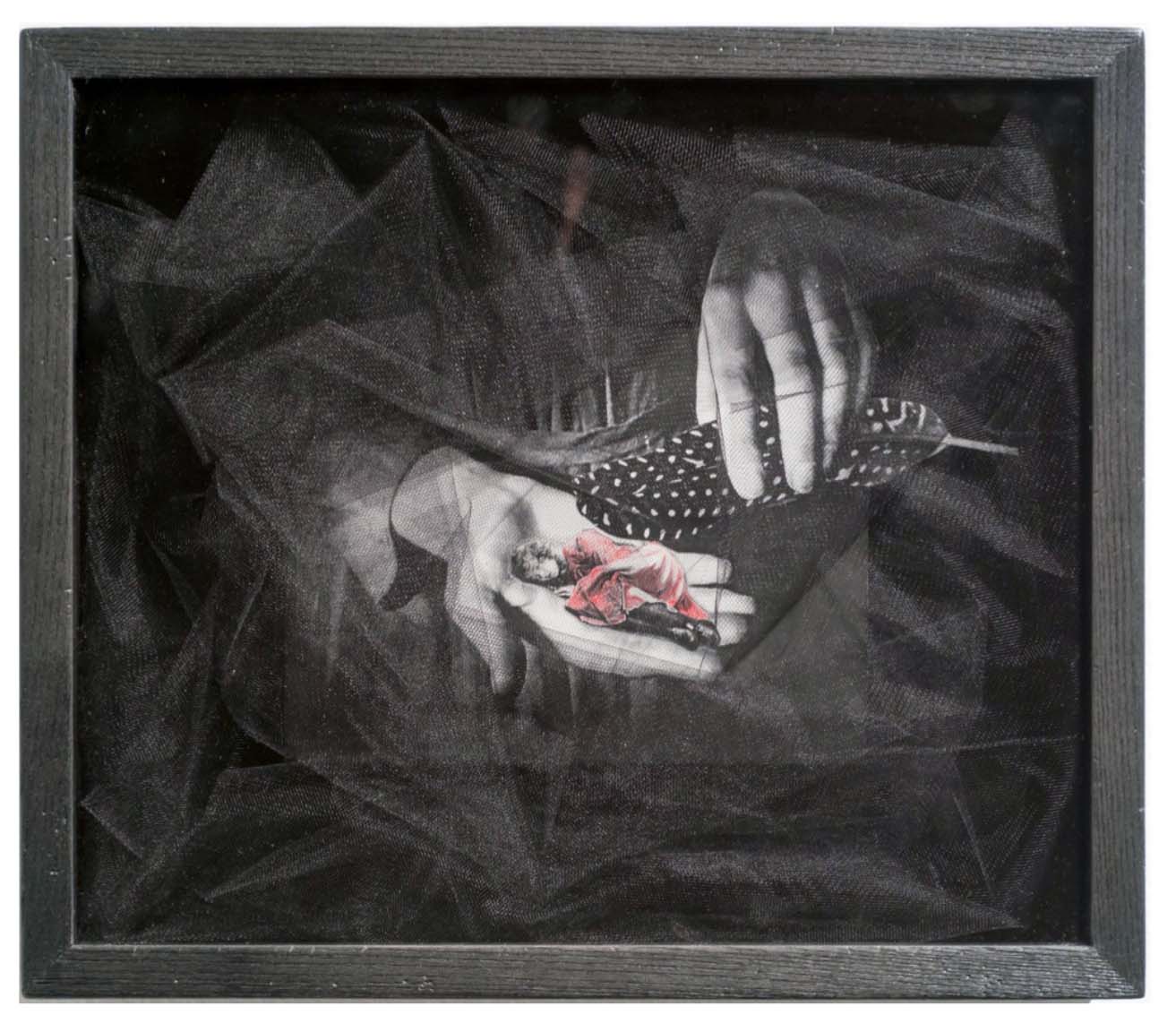

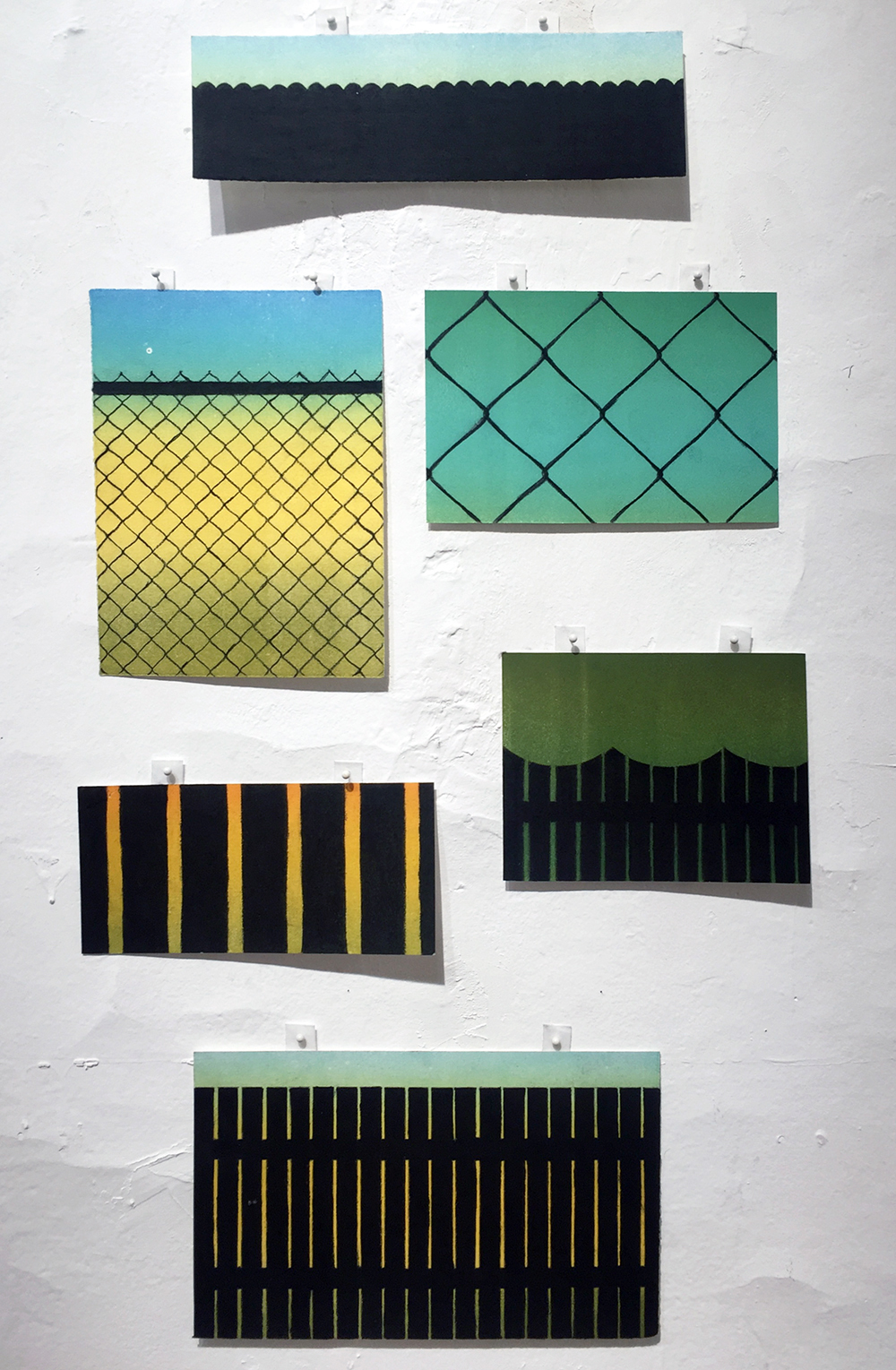

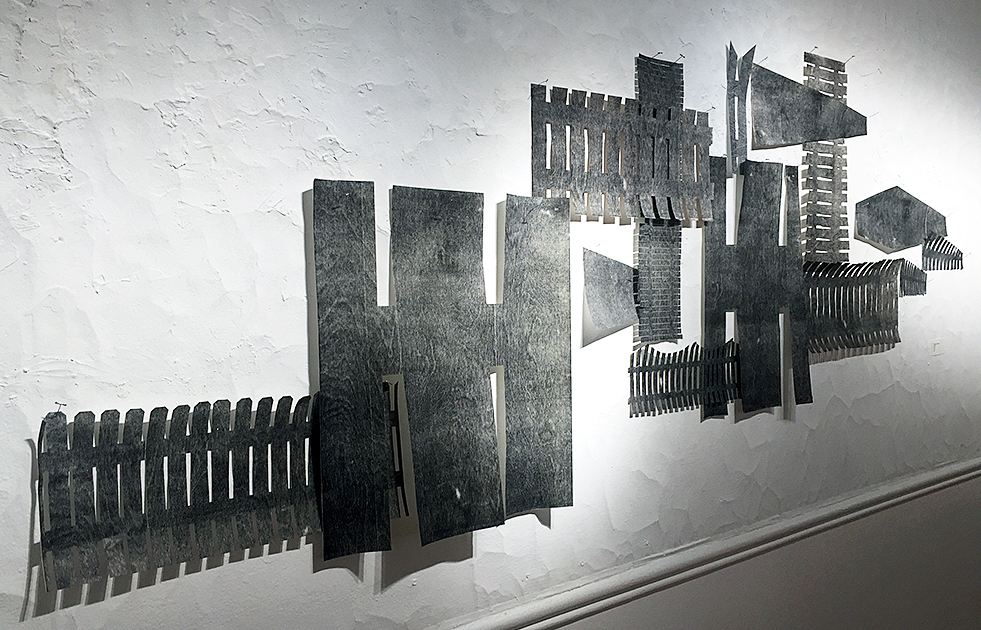

At David Klein, the use of the salon as both conversational gathering point and display methodology, stimulates an adventurous public viewing space. Rather than filling every wall from top to bottom and side to side, the work in the exhibition is broken down into intriguing groupings displayed on eight separate walls in the two gallery spaces. It would be a fool’s errand to extract a work or two from each group and create a “best of” series of highlights as the basis for an exhibition review. There is no star amongst the roster of artists here, culled from the gallery’s extensive exhibiting family. This is a group effort; each work assists the other as contrasts are amplified to deepen the conversation. Such collective resonance is where the true joy of “SALON” resides as hierarchies are erased. The graphic sits beside the painted. The drawn beside the photographic. The representational beside the abstract. The minimal beside the dense. The humorous beside the solemn. And so on and so forth. Such juxtapositions are the stuff of wildly active viewing. The exhibition hums with a vitality.

“SALON” Gallery 2 North Wall Installation

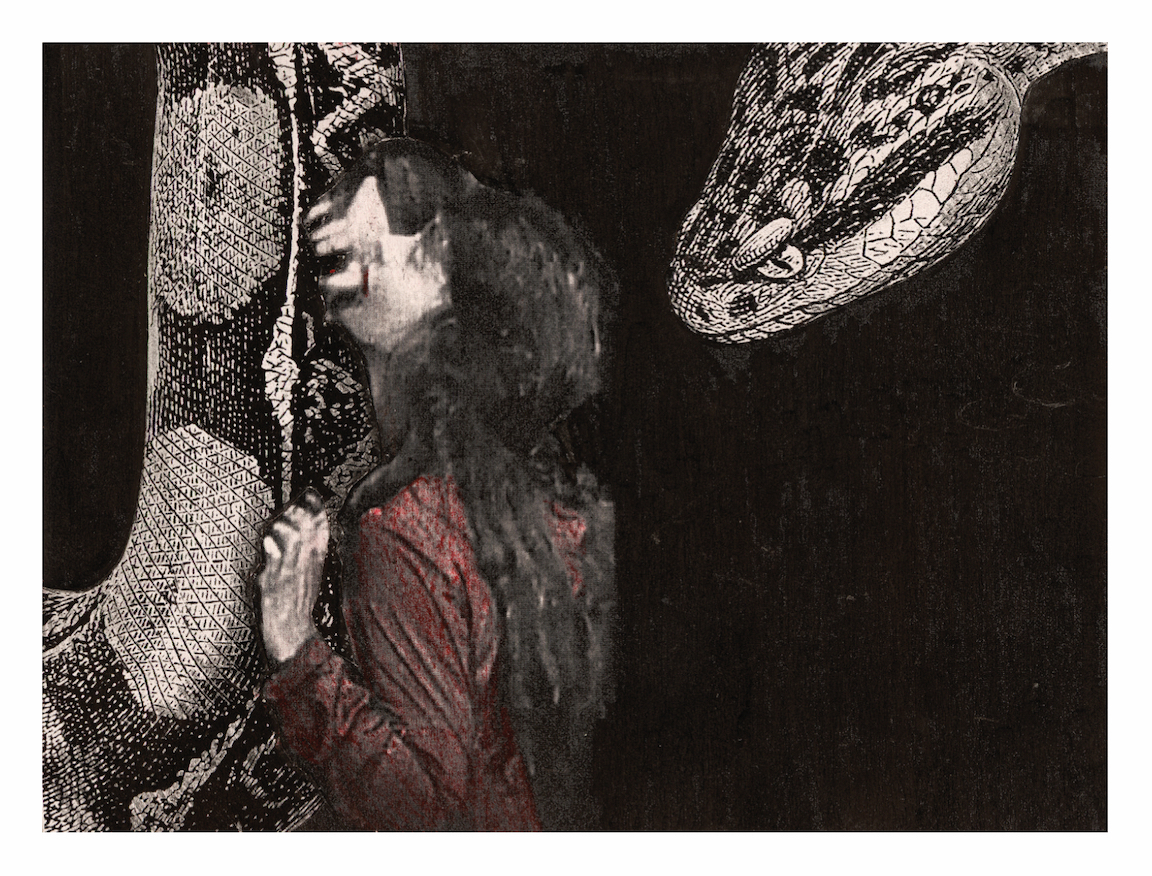

As a viewer moving from wall to wall, from conversation to conversation, one approaches the whole of each arrangement, marveling at the curatorial decisions resulting in unexpected formal juxtapositions. These configurations are the result of thoughtful installation on the macro level as well as care for content on the micro level. As one drills down into individual works, crowding in closer, examining each piece on its own terms, something occurs moving from one close inspection to another: the experience of the prior work lingers a bit more on the way to settling into the next. Like the exquisite sound design in a Robert Altman film, the voices overlap. On the north wall of gallery 2, the energetic collisions of Alisa Henriquez brush up against the hard-edged purity of Matthew Hawtin which finds a partnership with the carefully observed humanity of Mario Moore which is confronted by the mediated spectatorship of Jessica Rohrer which dissolves into the formal filigree of Janet Hamrick which simultaneously eases and bumps into the heightened temperature of Corine Vermeulen. There are many such moments throughout “SALON.”

“SALON” Gallery 1 South Wall Installation.

Realistically, “SALON” is an exhibition about availability. The works chosen are bite-sized morsels representative of a larger body of work by each artist, serving as distilled entrées into their concerns. Framed for ease of hanging and transportability, the majority of works priced at a modest level for a larger audience, such market concerns go hand-in-hand with the formal accessibility of the exhibition. Free of viewing images in isolation in support of a single voice, the communion on display in “SALON” is a liberating and welcoming experience. Rather than being instructed where to place one’s focus, there is a choice of attention. In an era in which digital platforms tailor our viewing habits with surgical precision, employing harvested algorithms to produce ever narrower windows on the world, it is good to be reminded of the virtues of pluralistic viewing. “SALON” is a social event that invigorates the necessity of wide-ranging cultural conversations, reinforcing a community of expression.

“SALON” Gallery 2 East Wall Installation.

“SALON” is Jamie Adams, Elise Ansel, Emmy Bright, Mitch Cope, Carlos Diaz, Joel Grothaus, Janet Hamrick, Matthew Hawtin, Alisa Henriquez, Patrick Hill, Scott Hocking, Cooper Holoweski, Trisha Holt, Cyrus Karimipour, Trevor King, Andrew Krieger, Stephen Magsig, Kim McCarty, Clara McClenon, Mario Moore, Carrie Moyer, Brittany Nelson, Marianna Olague, Judy Pfaff, Benjamin Pritchard, Kelly Reemtsen, Jessica Rohrer, Tylonn Sawyer, Robert Schefman, Julie Schenkelberg, Lauren Semivan, Clinton Snider, Rosalind Tallmadge, Corine Vermeulen, Liat Yossifor, and Elizabeth Youngblood.

“SALON” is on view at David Klein Gallery Detroit Until November 2.