Guggenheim Museum, New York City. All Images Courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum.

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present

Before a recent visit to NYC, I was set on visiting the new Met Breuer Museum (housed in the former Whitney Museum building) that is hosting a large photographic exhibition by Diane Arbus. But my interest in European Modernism pulled me away to the Guggenheim, which has mounted a major retrospective of work by the Hungarian artist, László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) who is unknown to me. The compilation of work is the first comprehensive retrospective of Moholy-Nagy, likely the first artist with a large and diverse field of media, including painting, sculptures, works on paper and Plexiglas, photograms and films. Despite his visibility as a Bauhaus teacher and artist, his profile has been little known to American art schools. This exhibition conveys the experimental nature of his work that includes industrial materials, movement, light, and a variety of photo-based images.

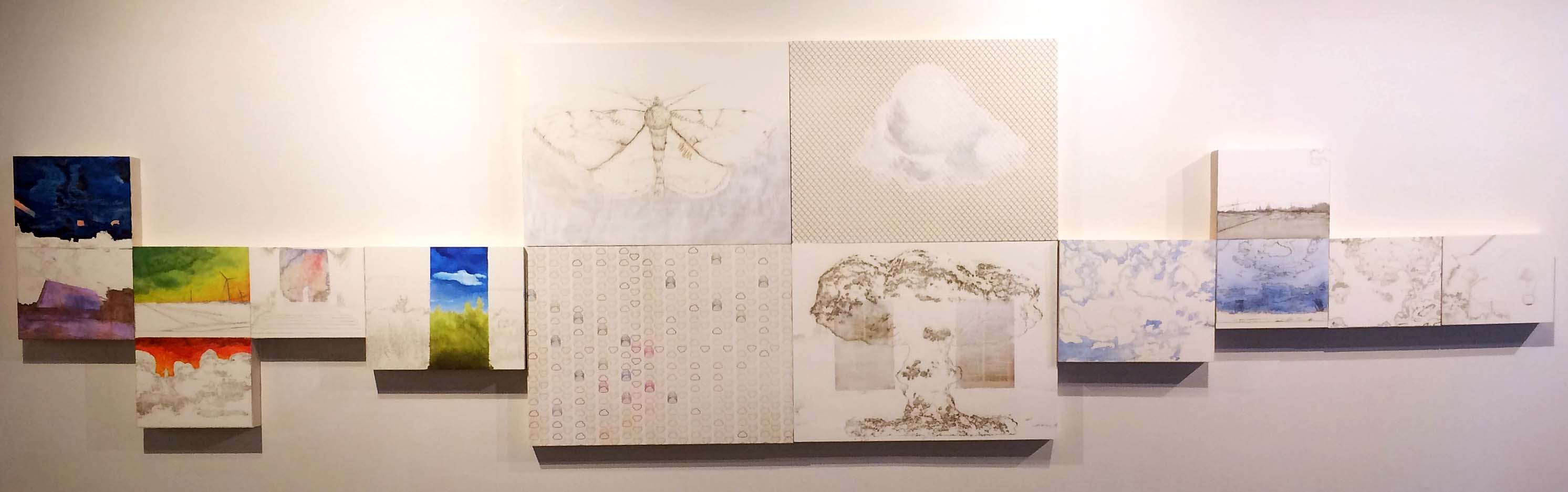

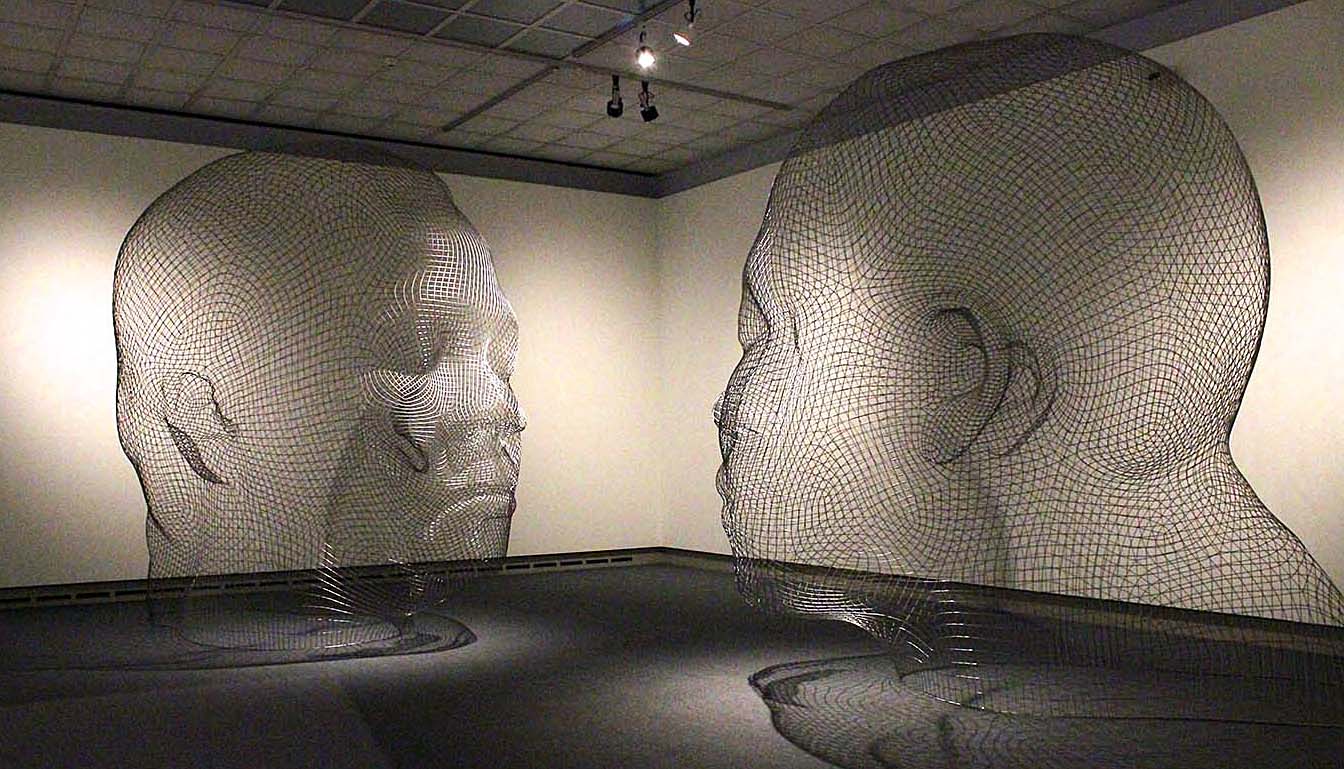

Installation View: Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Future Present, Solomon Guggenheim Museum, 2016

The Bauhaus School (1919-1933), meaning in German to construct, struggled to exist at three locations in Germany during the early part of the 20th century. Founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, in Weimar, it moved to Dessau in 1925 where it housed an artist faculty that included Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Breuer, and László Moholy-Nagy, and then finally ended up in Berlin for one final year until the Nazi Party came to power. The school specialized in fine and applied arts influenced by the Constructivism movement that originated in Russia in 1913 under Vladimir Tatlin, where art was practiced for social purpose, and included architecture and typography. Constructivists proposed to replace art’s traditional concern with composition, rather a focus on construction. For many Constructivists, this entailed an ethic of “truth to materials,” the belief that materials should be employed only in accordance with their capacities.

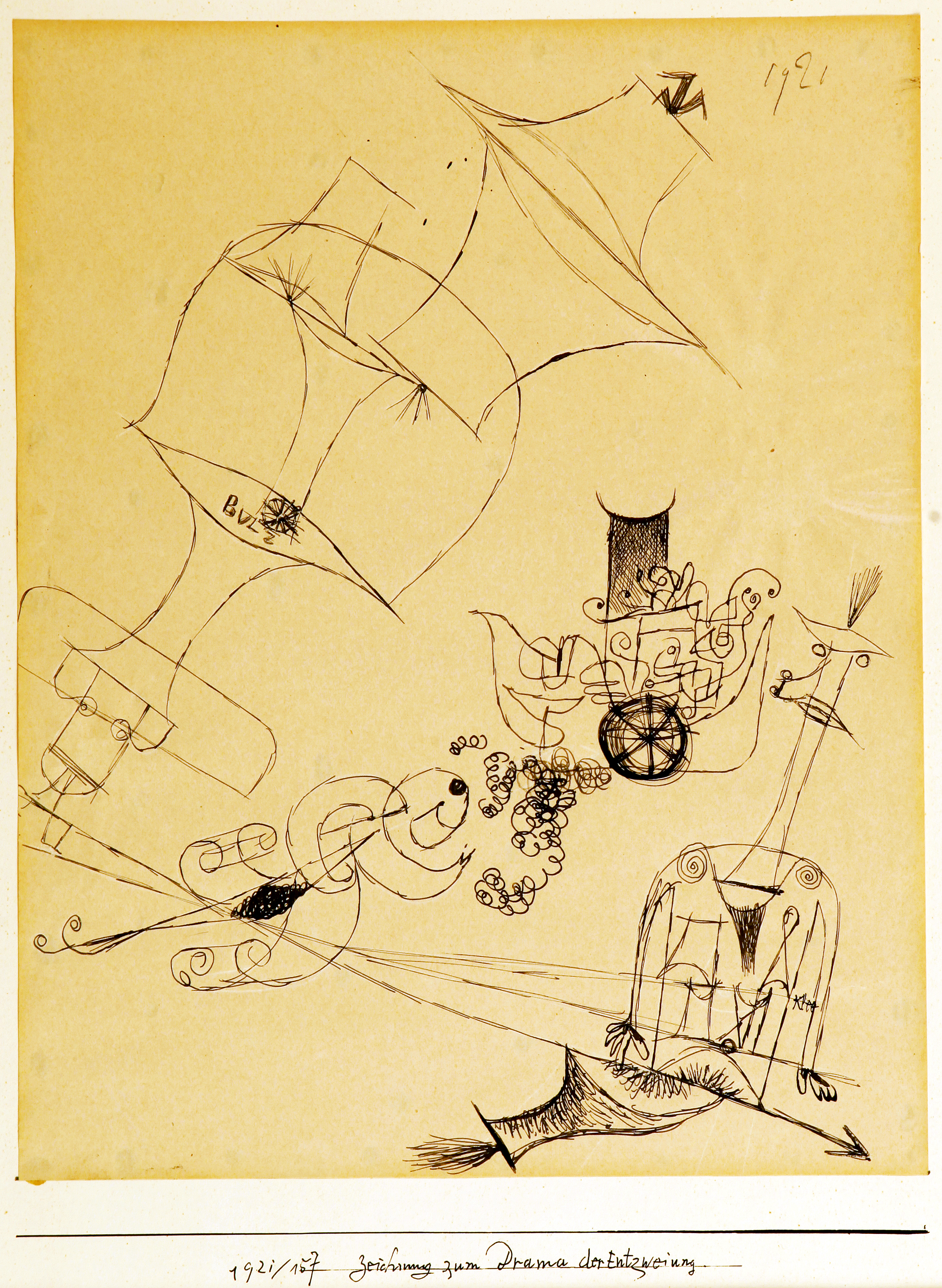

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, CH BEATA l, 1939, Oil and Graphite on Canvas, Collection of the Solomon Guggenheim Museum

Juxtaposed against German Expressionism, Moholy-Nagy creates an image that reminds this writer of Kandinsky in his large oil on canvas, CH Beta 1. A non-objective abstract composition, the work relies heavily on design and the use of space, line and color on a flat plane void of objective meaning. If Kandinsky is the father of abstract art, then Moly-Nagy is an apostle presenting a new venue of work for the modern world. Born in Hungary in 1895, he attended art school in Budapest before bringing his Constructivist aesthetic to the Bauhaus school in Dessau. The mechanical free-floating geometries influenced many artists in the United States to follow, including Frank Stella, David Smith, Ad Reinhardt, Sol LeWitt and Sean Scully.

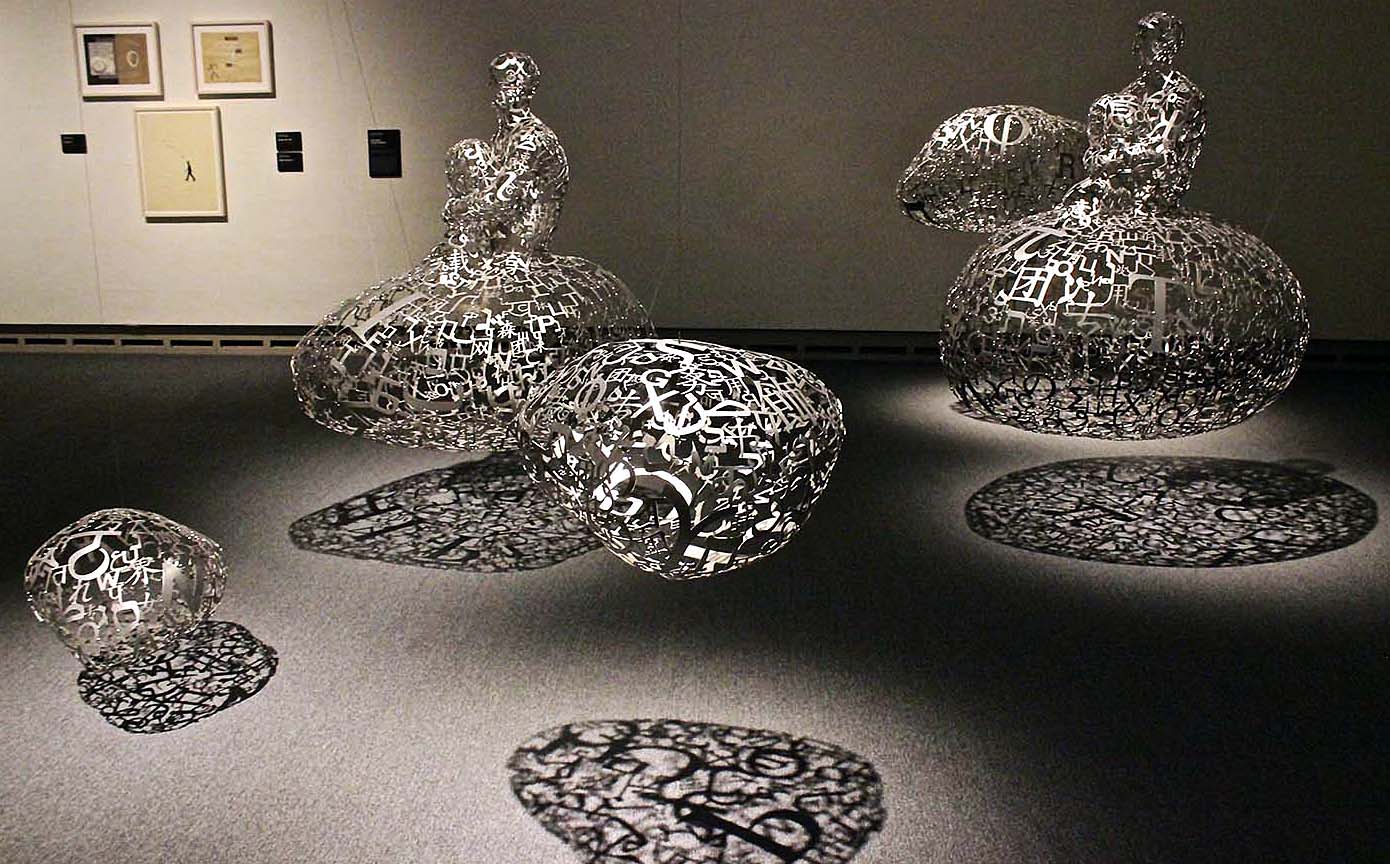

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Nickel Sculpture with Spiral, 1921, The Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

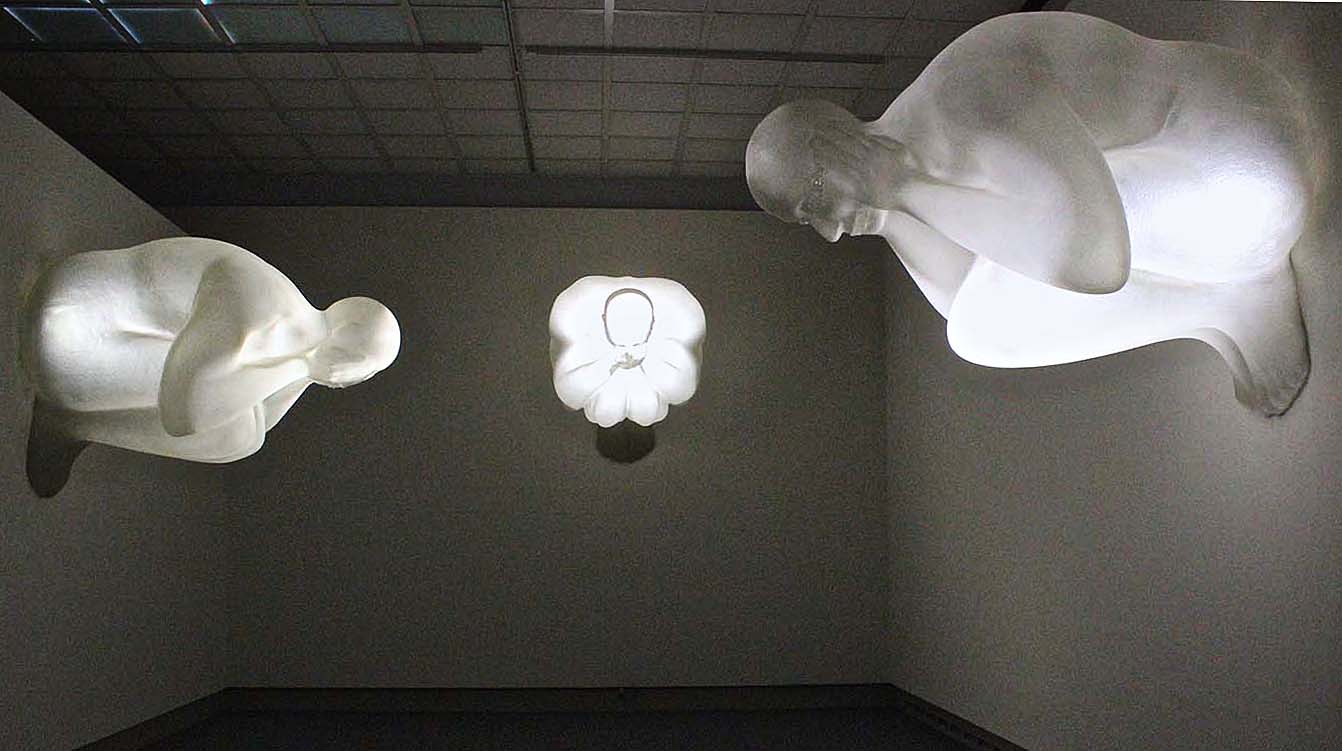

Moholy-Nagy’s nickel plated on iron-welded sculpture, owned by the Museum of Modern Art, demonstrates his industrial design and constructivist approach to the machining of objects and a spiral that inadvertently echoes the Guggenheim’s internal architecture.

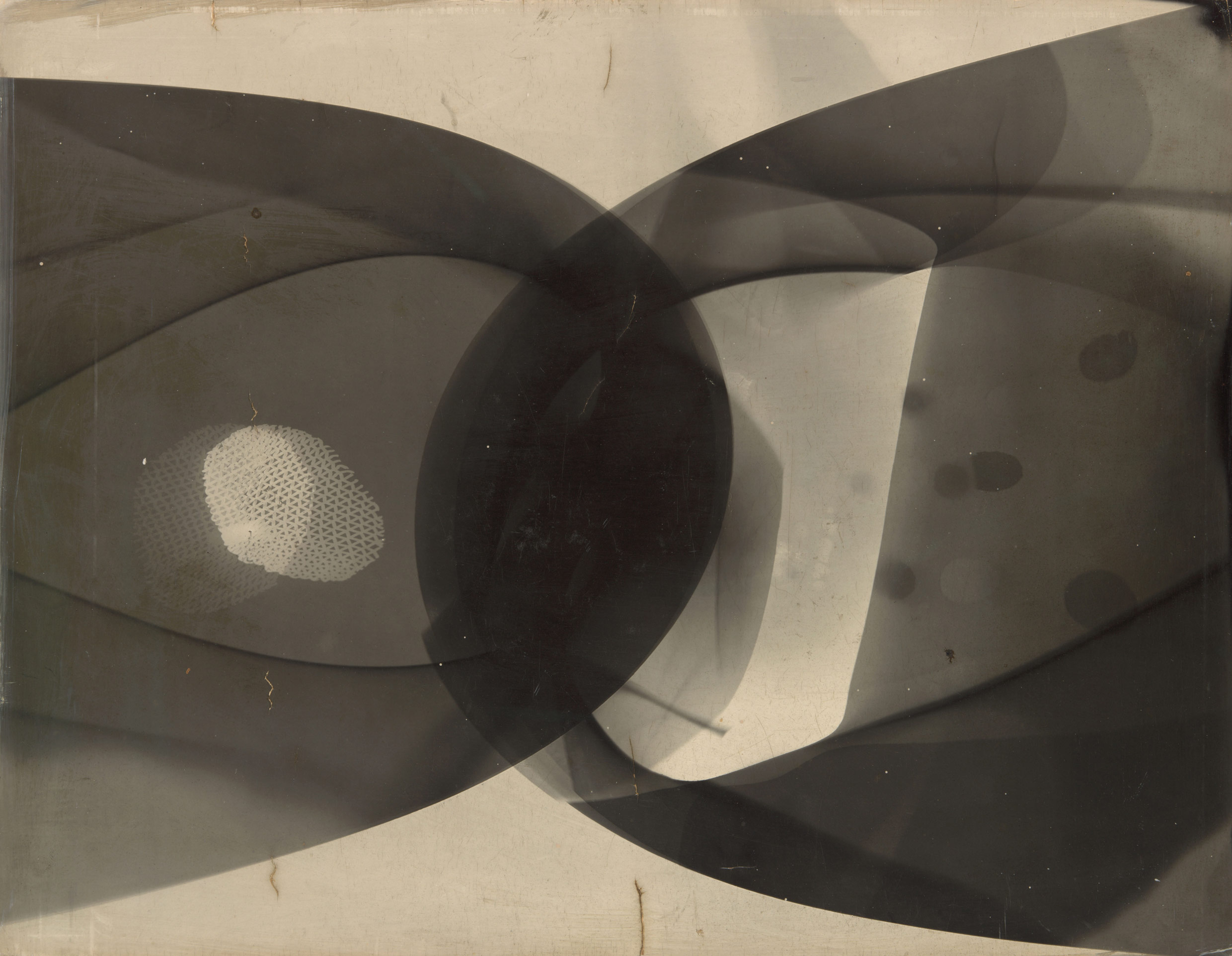

László Moholy-Nagy Photogram, 1941 Gelatin silver photogram, 28 x 36 cm The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Sally Petrilli, 1985 © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Collected by Hilla Rebay and Solomon Guggenheim, founders of the museum, this exhibition is beautifully arranged by Kelly Cullinan, the senior exhibition designer. I especially appreciated the extensive writings of Moholy-Nagy displayed on each level of the museum in vitrines. If I were still teaching painting at the college level, I would spend more time discussing European Modernism, especially the influence of the Bauhaus School and its teachers and artists.

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present is co-organized by Carol S. Eliel, Curator of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Karole P. B. Vail, Curator, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Richard and Ellen Sandor Chair and Curator, Department of Photography, Art Institute of Chicago. The Guggenheim presentation is organized by Vail, with the assistance of Ylinka Barotto, Curatorial Assistant, and Danielle Toubrinet, Exhibition Assistant.