Outside Work: Faculty Exhibition at Oakland University Department of Art and Art History

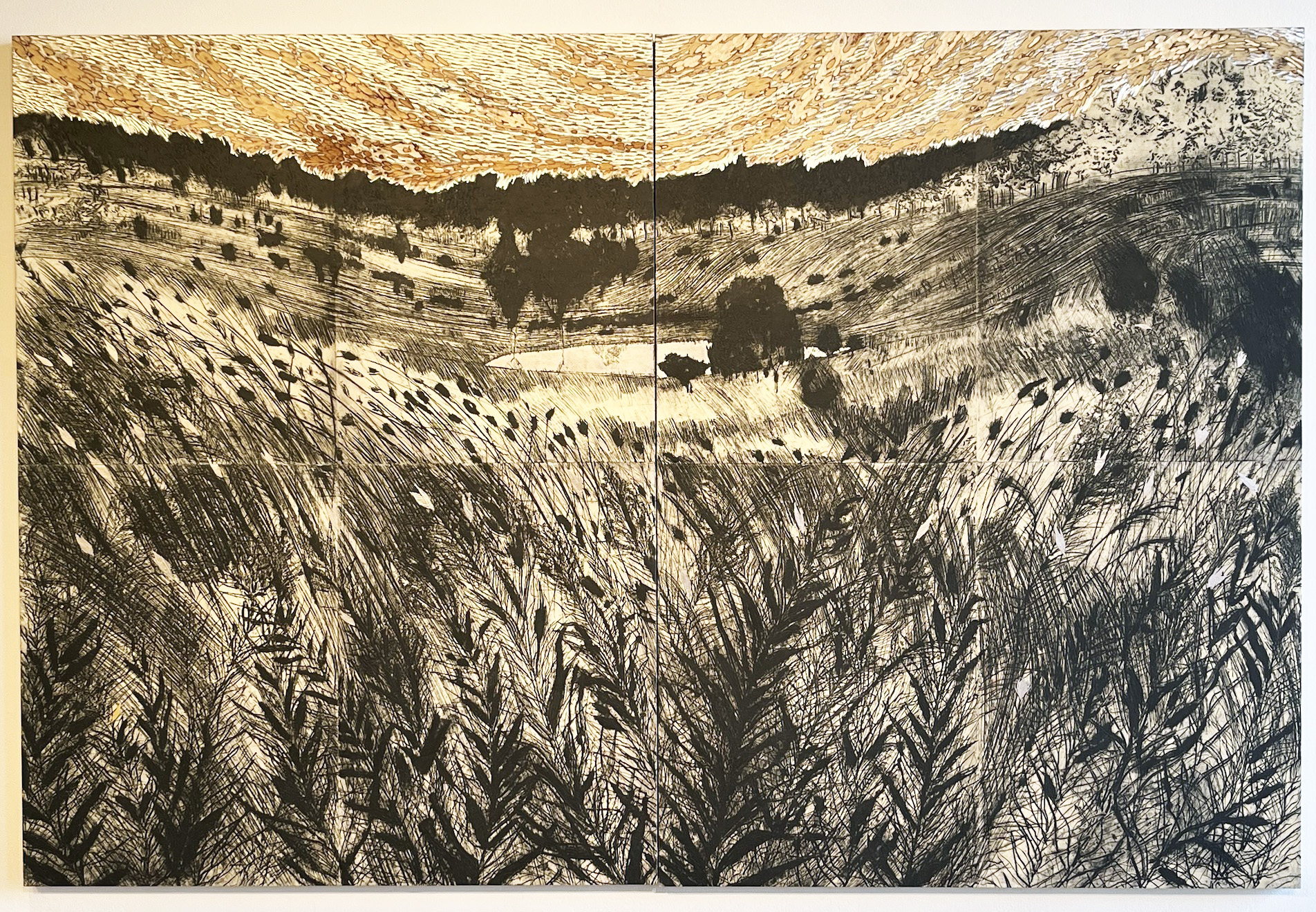

Installation view of Outside Work featuring Black Marquee, The Wild Bunch by Ryan Stanfest, and Getting Golder by Lindsey Camelio. All images courtesy of Ashley Cook

The promotional material for Outside Work at Oakland University Art Gallery includes an image of an organic object with a form similar to a bone or a piece of wood, lending itself to preconceptions that the exhibition would be focused on the natural outside world. Realizing upon visiting the work that this piece by David Lambert is a series of spoons carved from a native sycamore tree could pique the interest of nature lovers. The rest of the work, however, undermines from this assumption that nature is the consistent focus and quickly clarifies that what we have is a group of works by the faculty of the university done outside of their work within the Department of Art and Art History. Dick Goody is the director of the gallery and a Professor of Art at Oakland University; curated into the show are fourteen of his oil paintings along with other works of art by Claude Baillargeon, Meaghan Barry, Lindsey Camelio, Dho Yee Chung, Satareh Ghoreishi, David Lambert, Colleen Ludwig, Karen McGarry, Maria Smith Bohannon, Ryan Standfest and Cody VanderKaay.

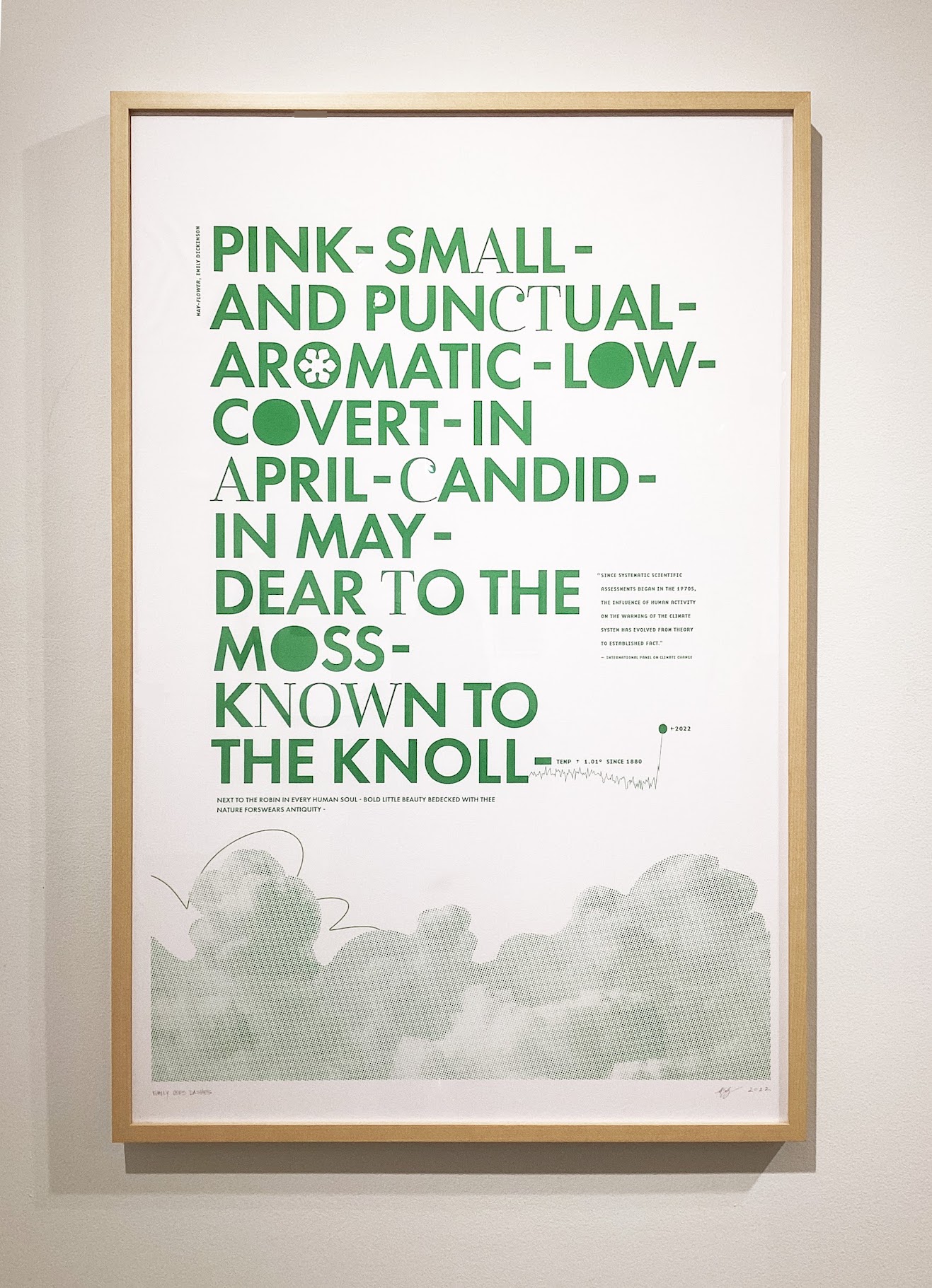

Maria Smith Brohannon, Emily uses Dashes, Glichee on canvas, 2022.

Visitors are first welcomed with a poster by Maria Smith Bohannon, who is an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design. This poster Emily uses Dashes places a strong focus on the poetic punctuation practices of Emily Dickinson in order to soften the heavy statistics of climate change that are peppered around the poetry. Eight conceptual maps by Karen McGarry are presented along the adjacent wall and then a second piece by Bohannon, Emily is Hopeful. The maps entitled These Places Thus Far by McGarry, who is a Lecturer in Art, utilize collage as the primary technique to touch on her experiences living in different places throughout her life as a student and arts educator, including Detroit, Chicago, New York, Oxford, Singapore, Dublin, Cincinnati and Los Angeles.

Dho Yee Chung, The Room Series, mixed digital media, 2022.

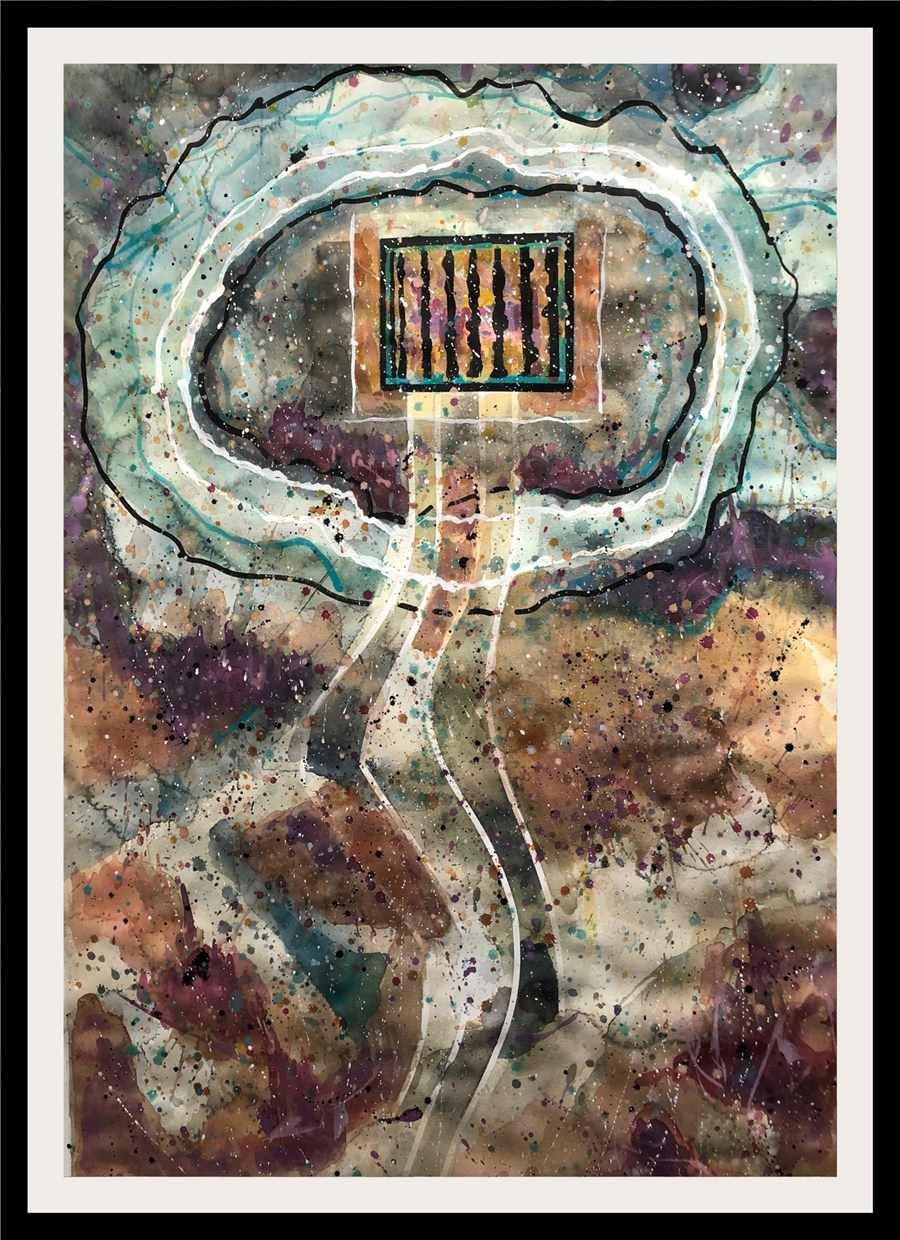

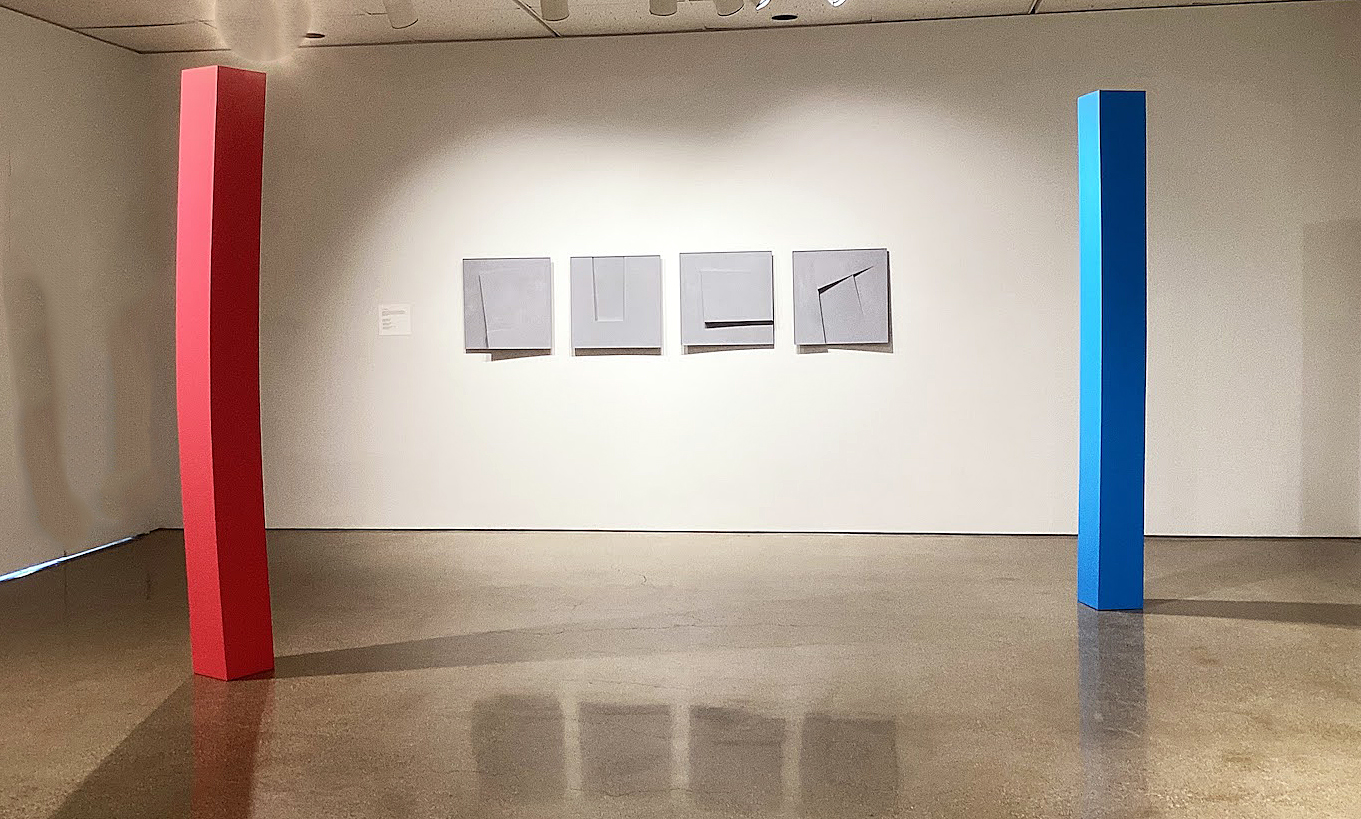

Works by Assistant Professors of Graphic Design Dho Yee Chung and Lindsey Camelio differ from each other despite both using digital media as their means of production. Dho Yee Chung’s triptych The Room Series uses surrealist compositions, missing ceilings and floors, animated walls, and translucent floating forms to depict the control of human labor within a digital workspace. Camelio embraces elements of surrealism too, but with the objective of exploring a realm between luxury and everyday life through odd combinations of subject, pattern, color, and form. A strong focus on color and form is also at play in the work across the room by Cody VenderKaay who is an Associate Professor of Art, the Director of the Studio Art Program, and a sculptor. These abstract red and blue towers are in fact made of pine despite them looking like plastic. This carries over as well to the gray wall works they frame, which are shaped and primed birch.

Cody VanderKaay, Lodestone (Roulette) and Lodestone (High Dive) made of shaped and painted pine, Untitled (Subliminal Landscape) made of shaped and primed birch, 2022.

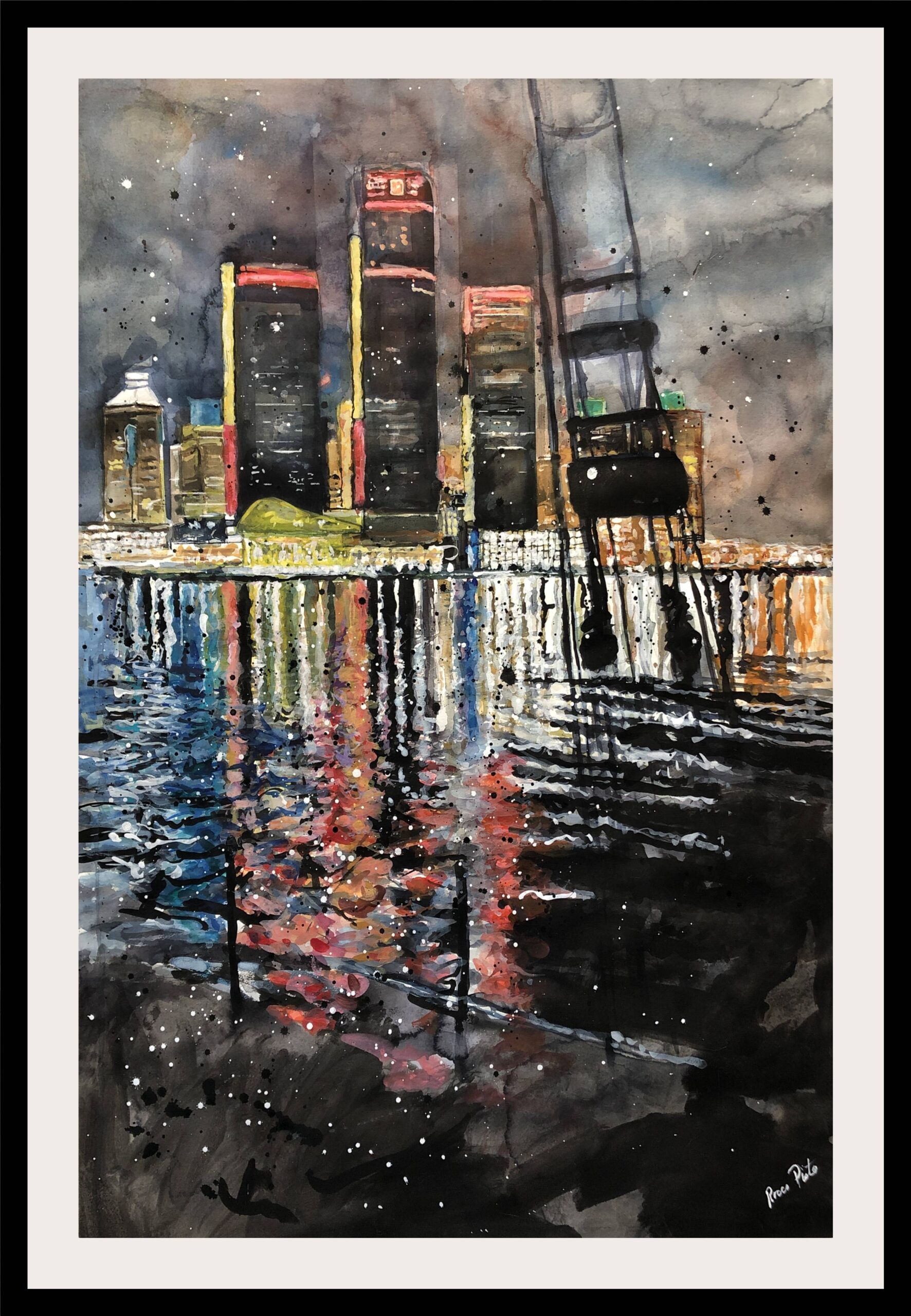

Assistant Professor of Graphic Design Satareh Ghoreishi and Assistant Professor of Art Ryan Standfest encourage us to consider the impacts of Covid-19 on consumerism around the world. The two works by Ghoreishi focus on the massive influx of online shopping that took place during the onset of the pandemic through her sculptural assemblages that combine contemporary shipping boxes and fashion items with personal items from years ago. The 3D collages by Standfest highlight the unfortunate impact that the pandemic has had on our ability to gather together in physical spaces. He touches on this through the display of two abandoned movie theater facades and a watercolor painting of a rundown marquee. Sharing the same space is Associate Professor of Art Colleen Ludwig’s crocheted fiber and mushroom root sculptures Saccu 1 and Saccu 2. They use the superorganism mycelium to test its ability to merge with fiber with the aim of discovering the potential for new habitat designs to house small creatures within the natural world. This work has a very particular concentration that combines biology with creative production similar to Untitled (Spoons) by Lecturer in Art David Lambert, who uses the tradition of spoon making from his Scots/Irish ancestry to produce these seven forms that teeter on the line between concept and function.

David Lambert, Untitled (Spoons), sycamore, 2020.

The long-standing painting practice of Dick Goody holds a place in this show alongside Professor of Art History Claude Baillargeon’s ink-jet prints entitled Memorial Monuments of Racial Terror, The Equal Justice Initiative (EIJ) Community Remembrance Project, and A Knight of Columbus Facing Justice. These photographs represent the Equal Justice Institute and its work in confronting the history of racism in the United States as a way of healing and achieving justice. And finally, the Department of Art and Art History Chair Meaghan Berry introduces her graphic design firm Unsold Studio through the presentation of six posters that were commissioned by the Michigan Opera Theatre’s 2021-2022 season In MOTion. These promotional designs were made for each performance in the season and visually communicated a freshness through the sense of motion with the goal of not only continuing to attract long-time attendees but new audiences as well.

Meaghan Barry, In MOTion: A visual identity system for Michigan Opera Theatre’s 2021-2022 Season, 2021.

The professional and personal concerns of the artists are represented through the work they chose to include in this group exhibition. Outside Work successfully highlights the dynamics at play within the Department of Art and Art History and makes it clear that each of these artists sustains a studio practice and active professional career in the world of art and design in addition to their position as an educator, which is an essential trait to the faculty of any distinguished university.

Outside Work at Oakland University Art Gallery opened on January 12 and is on view until April 2, 2023. You can learn more at https://www.ouartgallery.org/exhibitions/outside-work/