PHENOMENA IN LANDSCAPE: Paintings, Prints, Drawings, & Photographs 1969-2017

James Nawara, Professor Emeritus of Painting and Drawing at Wayne State University, PHENOMENA IN LANDSCAPE, Retrospective Exhibition, 2017 Image Courtesy of Lucille Nawara

The exhibition by Jim Nawara, now Professor Emeritus of Painting and Drawing at Wayne State University, spans forty-eight years and includes more than one hundred paintings, prints, drawings, and photographs. The exhibition begins with Nawara’s imaginary landscapes seen from an aerial viewpoint that were made in the seventies and eighties. Next, an engaging series of thirty-two black and white photographs (1969-1989) presents sometimes quirky subjects selected mostly from Detroit area urban landscapes. Some these compositions were influential sources for subsequent oil paintings and large watercolor paintings that Nawara has produced from 1990 up to the present. No longer seen from an aerial viewpoint, these representational landscapes are based upon observation and interpretation of actual sites that are carefully selected.

Nawara has stated that he often prefers depopulated, nondescript, or non-picturesque sources, “The subject does not need to be obviously beautiful, grand, or pristine. I once found the foundation of an abandoned house more intriguing than an idyllic nearby waterfall. A large globe light set in a library lawn below a harvest moon, the geometric pattern of a partially demolished Detroit factory, and the stark, nighttime shadows on snow covering a backyard garden all became painting subjects.”

James Nawara, Installation image, Early work, Image Courtesy of DAR 2017

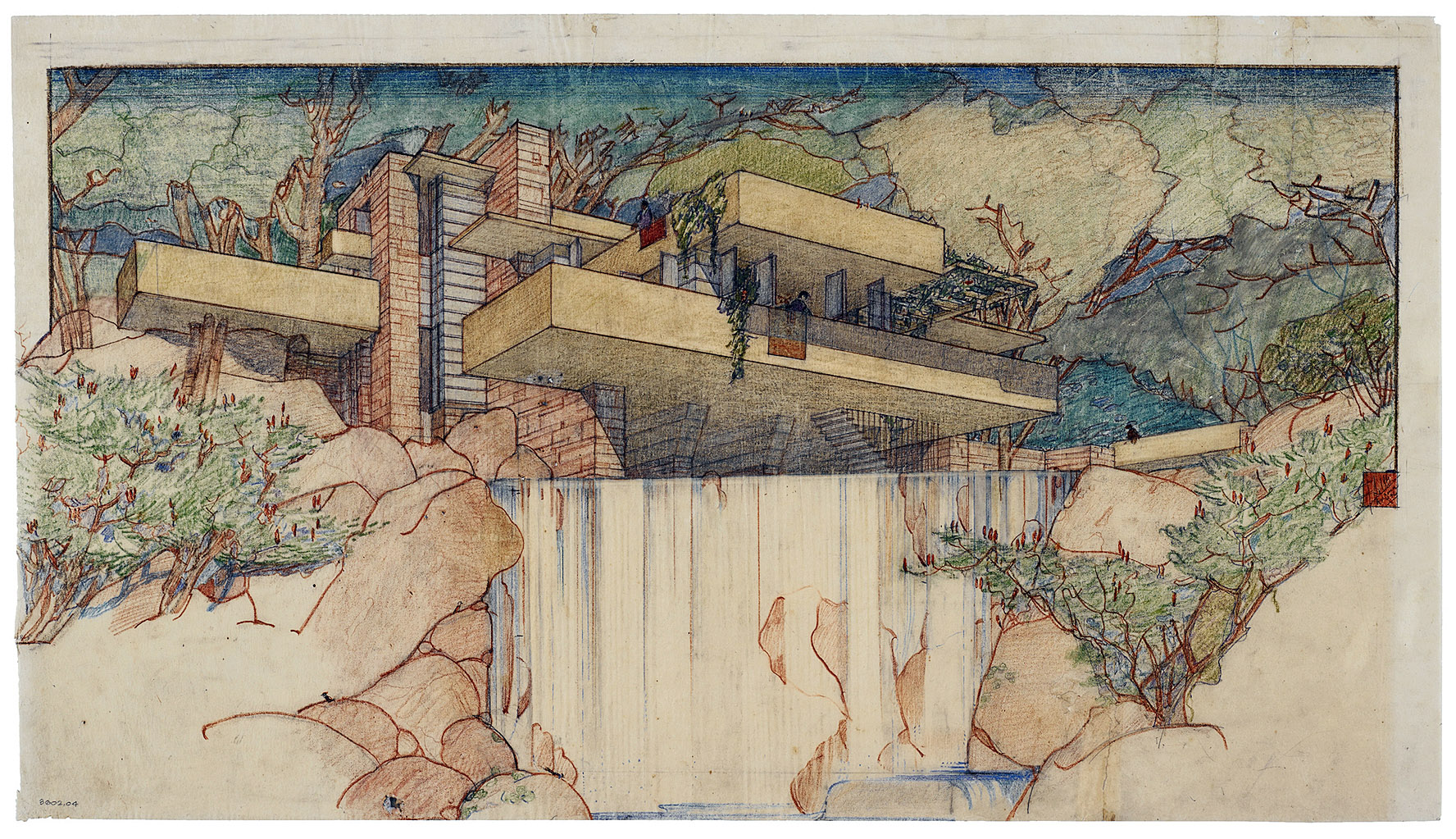

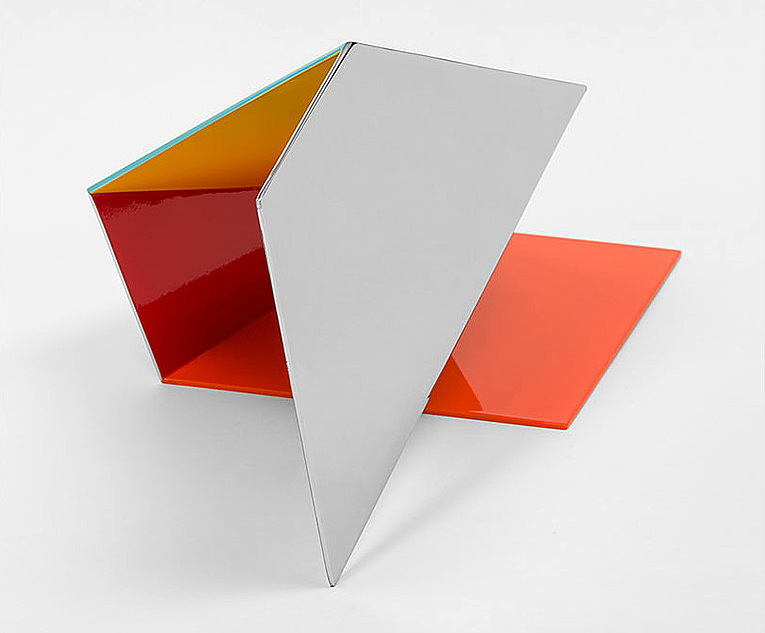

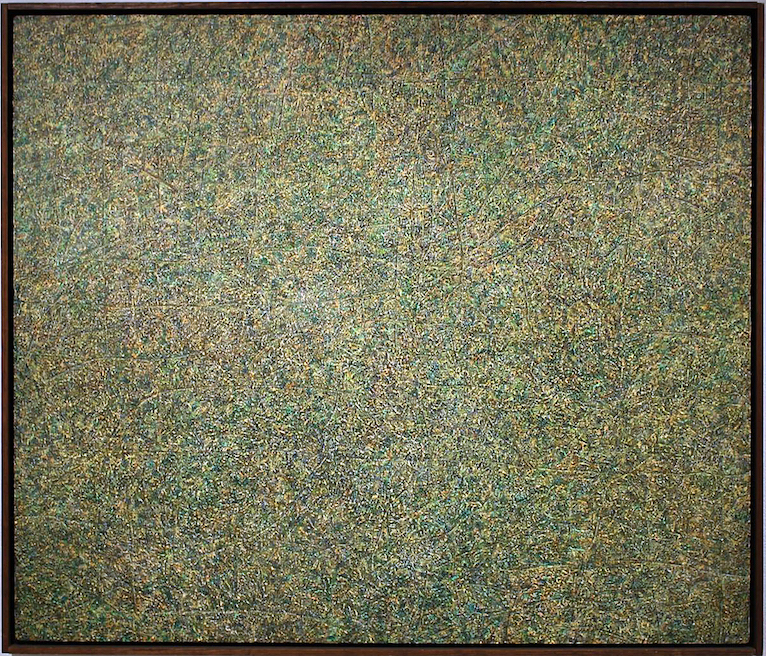

In the earlier imaginary landscape subjects, the terrain was seen from a low-altitude aerial viewpoint. Although invented, these compositions evolved from actual landscapes viewed from commercial flights, light aircraft, a helicopter and once a hot air balloon flight, as well as the artist’s interests in geology, optical phenomena, and prehistory. At a distance, the work might suggest abstract color field painting, exemplified by abstract color field painters like Jules Olitski in the 1980’s. Upon closer observation, the details reveal a plausible landscape that provides illusions of crop growth, archeological sites, subtle patterns, rock formations, long cast shadows, with both actual and illusionistic textures. These works have a feel for abstraction, something that would be carried through in Jim Nawara’s later work.

James Nawara, Trace, acrylic on linen, 1973

As an undergraduate at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Nawara studied under the mentor and famous photographer, Kenneth Josephson and also worked as a commercial photographer in Chicago. He went on to graduate school in painting at the University of Illinois, and studied photography there under another well-known photographer, Art Sinsabaugh.

James Nawara, Thirty- Two early Black & White 8 x 10″ Photographic Images

After completing his graduate degree in Illinois, Jim Nawara moved to Detroit to take a position as a drawing instructor at Wayne State University. His thirty-two photographs in this exhibition, most of which were taken in Detroit, have seldom been exhibited. He chose the rigor of always composing and printing the images full frame, un-cropped. The dates of these images overlap Nawara’s shift from aerial view subjects to landscapes based on ground-level views of actual sites. He was intrigued by the idea that an artist might be able to make art out of a “mundane” subject.

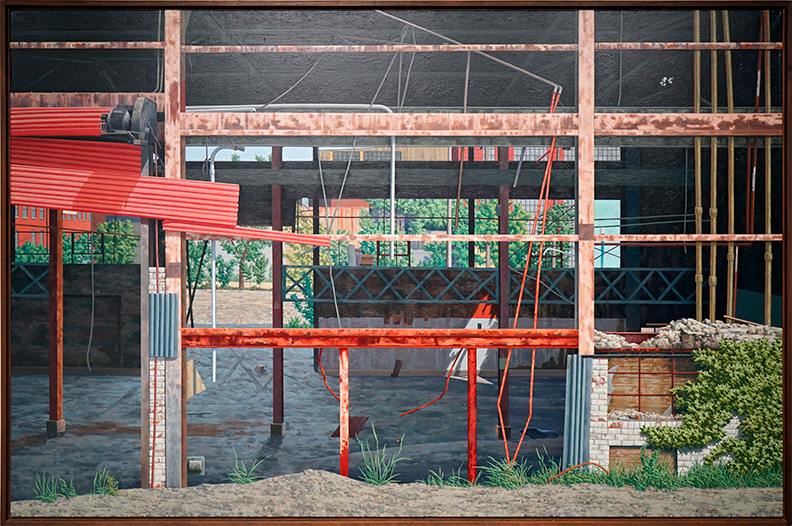

James Nawara, RESTEEL, oil on Linen, 1991

In the large industrial urban landscape, RESTEEL multiple layers of broken walls and windows of an abandoned factory draw the viewer into the painting. The foreground, mid-ground, and background all have their characteristics concerning light, shape, and color. It is an example of magical realism that presents an abstraction that is grounded in realism. In the foreground, the lower right brick structure plays off the left sheets of corrugated red metal, while the interior plays with a sliver of light. The imagery is divided into thirds both vertically and horizontally. It is a grid that provides us with a solitude that brings us back to multiple viewing. Each section of this oil painting is meticulously rendered, another reason viewers are compelled to take a long, hard look and become enveloped by this vestige of Detroit’s industry.

James Nawara, Blue Fence, oil on linen, 1999

In the small oil painting, Blue Fence, from 1999 is another example of Nawara’s strong composition, illusionistic space, and placement of color. He painted the blue fence, as well as a wedge of a red, white and blue sign on the far right in crisp detail. The fence, sign, shed walls, roof, and tree are carefully layered, like flats on a stage. It is evident that placement of these compositional elements is like an abstract collage.

James Nawara, Night Garden, Watercolor, 2007

Nawara’s Night Garden demonstrates a high level of technical facility with the watercolor medium. He poetically creates the stillness of fallen snow in his wife’s vegetable garden, illuminated by a strong floodlight on the back of their studio.

Working from a photograph, Nawara translated the textured snow with granulated watercolor washes, particularly as seen in the snowdrifts and snow-covered birdbath. This was an ephemeral subject, as all the snow melted by dawn. The entire painting was done with just three granulating watercolors, Holbein Ultramarine Blue Deep, Daniel Smith Lunar Black, and Holbein Prussian Green.

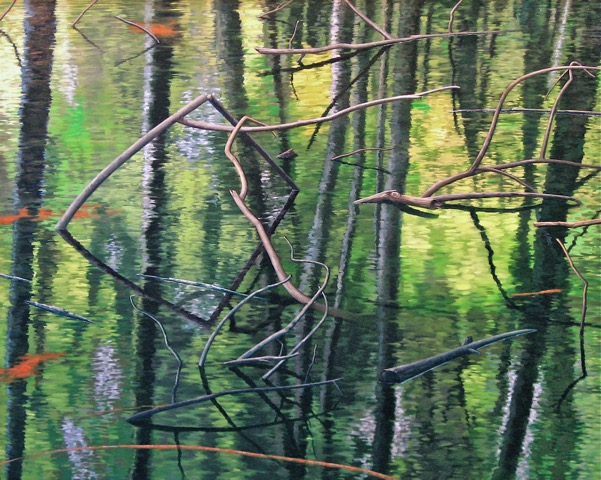

James Nawara, RHOMBUS, 40 x 50, oil on linen, 2008

Nawara’s 2008 40” x 50” oil painting RHOMBUS was used on the announcement for this exhibition. A rhombus is a geometric term for a parallelogram, like the shape of a diamond on playing cards. The rhombus in this painting is formed by a broken branch and its reflection in a flooded young woodland. Nawara was intrigued by the shimmering soft focus of the water surface, and the reflections of trees appear softly blurred by breezes, while the actual branches were rendered in sharp focus. Magic realism is in full play with this abstract composition, far from anything a traditional landscape painter would contemplate. Jim Nawara was pleased when a former student described his exhibition as “dreamlike”.

I had an opportunity to ask the artist a few questions:

Ron Scott: The title of your exhibition is PHENOMENA IN LANDSCAPE. What are some examples and what do you mean by Phenomenon?

Jim Nawara: Anything that may be of visual interest that is happening or that has happened in the landscape; also the evidence, or traces of natural and human activity in the landscape.

RS: When did the move from aerial imagery to horizon-based landscape take place and why?

JN: Actually, I made my first real drawings when I was about six years old and these were graphite pencil aerial view landscapes! This was after my first airline flight from Chicago to Minneapolis. My dad worked for Northwest Airlines, and he took my brother and me on a round trip to give my mom a one-day break. I was blown away by the views out the window and made drawings of what I saw as soon as I got home. Many years later I started drawing and painting aerial views again as a graduate student at the University of Illinois. Then after about twenty years, I moved away from aerial view landscapes in the late eighties. I felt that I had plowed the aerial view field thoroughly, and I wanted to move to other aspects of landscape.

RS: How much of the work is plein-air and how important is that process to the work?

JN: I have started a few paintings outdoors; but being a slow painter, I have never completed one outside. I found it stimulating, and I just kept seeing more and more information that I wanted to put into the painting! I use quick graphite sketches and photographs to define the compositions. I worked outside for two consecutive days on RESTEEL, the six-foot painting in this exhibition. Each day within two hours of my arrival the wind increased moderately, and the six-foot canvas turned into an uncontrollable sail pulling itself and me down the street!

RS: What role has photography played in your artwork? How is it used?

JN: My photography experience in and out of school has given me a good understanding of the differences between human vision and the way a camera records an image. This is crucial in understanding how to use a source photograph effectively for another medium.

RS: How would you describe the difference in oil on canvas work, and the works on paper? Is it more than scale? Is there something inherent in the media?

JN: Yes, oil and watercolor are just inherently different mediums with their characteristics and qualities. I enjoy both and often alternate between the two. The major difference is the fact that transparent watercolor dries rapidly and allows you to move forward quickly in a painting. However, you are very limited in removing color that has dried into the paper. Therefore, I have to plan out each watercolor several steps ahead. Oil paint allows you to move forward and back more easily, but each has its particular, wonderful charms.

RS: Which (living or dead) artist’s work are you most attracted to, and why?

JN: There are many wonderful artists who made excellent work. The first three that I immediately think of are Edwin Dickinson, Georgio Morandi, and (always) Johannes Vermeer. Check them out in books or online, but better yet, try to see some actual work in museums.

RS: What attracted you to these abandoned Midwest locations?

JN: I never select a site to paint because it is abandoned, though some are. I primarily consider my paintings abstract organizations of shape, color, light, and space. The paintings are always interpretations filtered through time, memory and imagination, as well as the physical process of painting. I often choose urban landscapes, but when I select a natural subject, I am interested in the effects of human activity great and small on the landscape. These events may be grand, unimportant, profound, or peculiar. I want to engage the viewer and to express something that is ineffable. My watercolor painting Lock shows a mosquito-ridden abandoned canal lock in Ohio that provided enough visual interest for me to make a painting.

The work in this exhibition spans Jim Nawara’s forty-six-year career as a professor of drawing and painting at Wayne State University. Artists and colleagues that know Jim kid him about his “brief” resume, a reflection of his record as an active exhibitor participating in solo and small group shows as well as more than 250 international, national and regional group exhibitions, not to mention the public and private collections that house his work. In 2007 Nawara had an exhibition at the Muskegon Museum of art, Overviews & Afterlands, that exhibited 22 works of art where the curator remarks say, “His landscapes are without figures, yet notated with marks of human activity and man-made forms. They are based on observation but driven by invention. They reflect the passage of time: changing light and shadow, remnants of man-made forms, the layering of a medium during the creative process.”

Jim Nawara earned a B.F.A from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an M.F.A from the University of Illinois, Champaign

The exhibition continues through Friday, December 8th, 2017

Wayne State University Art Department Gallery

Hours: Tuesday – Thursday 10 AM – 6 PM, Friday 10AM- 7PM

Art Department Gallery, 150 Art Building, 5400 Reuther Mall, Detroit, Michigan 48202