Detail of Installation View of “Scott Hocking: Old” Photo courtesy of Robert Hensleigh

Some sixty years ago, in the spirit of the Avant-garde, earthworks artist Robert Smithson– among other American artists like Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Sol Lewitt—attempted to escape the confined space of the traditional artist’s studio, and to undo the tyranny of studio practice by redefining its traditional image/object making , and by commencing what he called an “expeditionary art.” Taken to meandering the industrial landscape of Passaic New Jersey, Smithson took Instamatic photos of commonplace industrial infrastructural constructions (bridges, smokestacks, drainage pipes) and, like Duchamp did with commonplace artifacts he called “readymades,“ Smithson re-recognized industrial infrastructure as monuments to civilization. Eventually also touring Mayan Mexico, he inserted mirrors in odd locations of the landscape to multiply and redefine Mexico’s already surreal visual landscapes. Smithson finally explored the arid landscape of the American West where he created his Spiral Getty, the greatest of American earthworks, on the Great Salt Lake.

Scott Hocking, a kindred Detroit artist founded a similar practice two decades ago by meandering and drifting through the eroding landscape of Detroit. Out of found materials appropriated from abandoned factories and office building, he created ephemeral monuments of the derelict remains of the city; at once archeologist and alchemist, he photographed them as part of the project. Among his many captivating projects Hocking created a huge stone egg in Michigan Central Train Station. He constructed a ziggurat in the Fischer Body 21 factory. He built a pyramid of abandoned car tires on a suburban lawn. Hocking has continued that practice on an international level with 22 site-specific projects throughout the world to date including works in France, Germany, Australia, Iceland, China, as well as throughout Michigan, Florida, New York; he now returns to the confinement of the Gallery space with an understated, thematically charged exhibition.

Scott Hocking, “Old,” 2018, gypsum, patina, salt.

“Scott Hocking: Old” returns him to the traditional, white box space of an art gallery at the David Klein gallery, and is a challenging summation of Hocking’s artistic process.

The center piece of the exhibition is the Klein Gallery’s Greek column that sits in the main entrance of the gallery. Riffing on the catacombs of Paris (which he visited) where the skeletons of millions of Parisian inhabitants were removed from cemeteries and placed in the ancient stone mines under the city, Hocking saw Detroit, as literally built upon the bodies and excruciating labor of human beings (autoworkers?). Symbolically surrounding the Klein gallery column (Hocking sees it as a huge structural bone) are thousands of bones and skulls cast by Hocking of hydrocal, made from locally mined gypsum, directly echoing Hocking’s own experience in the Paris catacombs, creating a monument to the souls that created Detroit. Somewhat macabre but in the tradition of gothic cemetery imagery, Hocking’s column, painted with a copper patina, and surrounded by a ring of salt crystals (mined from the ancient sea bed beneath Detroit), reflects his own family history of Cornish copper miners who worked in copper mines, thousands of feet underground, in Northern Michigan.

Punctuating the front room of the gallery, are six inscrutably mysterious artifacts created by Hocking of copper and tin and that are symbolic of the ancient history of copper mining in the Great Lakes area and of the presence of copper everywhere, from decorative architectural elements to the copper wire in Detroit’s electrical infrastructure. Most notably, “Country Boy,” the labyrinthine block of tangled copper wire in the front window of the gallery, is a “portrait” of a copper scrapper (homeless people who surreptitiously remove copper from derelict buildings and sell it) from whom Hocking bought the coiled wire. Country Boy, one of the many scrappers who Hocking had befriended in his research, had been killed in a hit and run. Like many of Hocking’s pieces it is at once a singularly amazing object and, like much of Hocking’s art, a spot-on invention.

Scott Hocking, “Country Boy,” 2003-2018, copper wire, 18”x16”x11”

Photographic documentation of Hockings projects fill out the exhibition, including photographs of a 2015 site-specific sculpture that he composed of, and on the site of, an eroding barn in the “thumb” area of Port Austin, Michigan. Commissioned by an area farmer (this is the second barn-art commission in the area), Hocking raised a collapsing 19thcentury barn and rebuilt it “upside down” to create an as big-as-a-barn, ark-like sculpture in the middle of a farm field. A recent excursion to see the project revealed a hallucinatory-like structure amidst an enormous farm field. Walking toward the ark from half-mile distance, across the field of ankle-busting clods of furrowed mud, with the drama of a huge sky of scudding clouds as a backdrop, combined to create a dizzying, biblical-like experience. The eerie, voice-filled, wind, epic sky, huge, distant trees waving in slow-motion, evoked an unforgettable cinematic presence.

“The Celestial Ship of the North”, Port Austin, MI. Photo by Robert Hensleigh

Collectively, there is an uncanny element in Hocking’s site-specific projects where one perceives multiple forces, both metaphorical and real, and an esoteric body of ideas such as astrology, alchemy, and astrotheology, at work. In Hocking ‘s description of the origins of the Barnboat (also called The Celestial Ship of the North and Emergency Ark), he refers to an Egyptian myth that depicts the crescent moon, waxing or waning, floating upon the horizon of the sea as an ancient version of Noah’s Ark. Like the ancients then, Hocking relies upon observation of the forces of nature, the planets and moons, and myths and cosmologies to situate his art. His “Celestial Ship of the North” refreshes our mythological eyes and prepares us to see, like Smithson’s Passaic Industrial landscape, the world in a different light. He sees the world, not in terms of art history and its successive permutations, but in terms of mythologies, ancient history and material culture. Most of Hocking’s many site-specific installations have been destroyed, removed, or lie remotely inaccessible, but the energy and visionary magic that created them resides in the documented photographs.

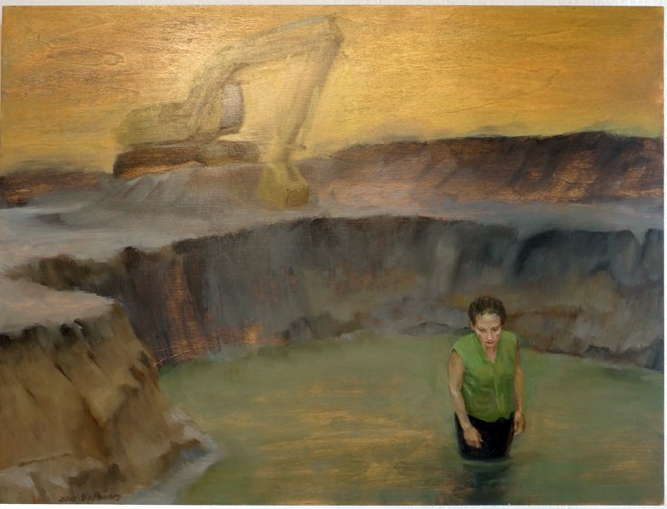

Scott Hocking, “Triumph of Death, Mounting a Dead Horse, 1/11,” 2010, Archival Inkjet Print, 33”X49 1/2”

In addition to photographs of the Barnboat there is documentation of four other site-specific projects in “Old” that captures the energy and immediacy of Hocking’s process. In a residency at famed Australian artist Arthur Boyd’s home, among the uncanny, serendipitous and inspired events in Aboriginal landscape, Hocking discovered a photograph of another Australian artist, Sidney Nolan, mounting a dead horse. In the Australian outback of Boyd’s property, Hocking discovered the bones of a cow that had been devoured by another creature; he reassembled them into the shape of Sidney Nolan’s dead horse, and then photographed himself attempting to mount it. Like a movie still that evokes the movie’s story, Hocking’s photo is a surreal instance of the strange domino effect of the forces (art engenders life) that create meaning in art or life.

All the processes that Hocking employ suggest an engagement with entropy, of exploring the fallen world, and of a Sisyphean rebuilding of it in various layers and forms—from egg to ziggurat—from rebirth, to going to the mountain to communicate with the gods—carefully manipulated in stacked arrangements, expected to crumble, but that at once coherent and transformative and even alchemical. As we spoke at his recent talk at the Klein gallery he bemoaned the fragile, degenerating quality of photographic documentation but optimistically, hoping for future technologies to preserve his work. Hocking commented, “These images will probably last only a hundred years.”

Scott Hocking, “Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark) aka The Barnboat, 1/11,” 2016, Archival Inkjet Print, 33”x49 ½”

Scott Hocking, Old, at David Klein Gallery through June 23,2018