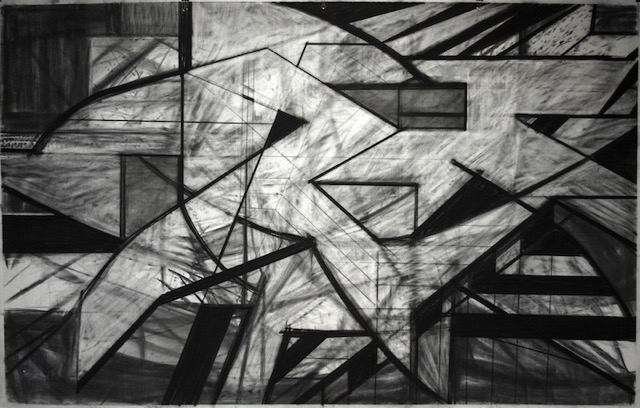

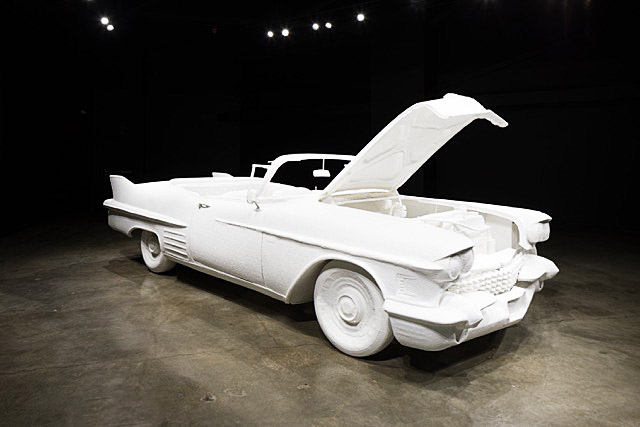

Looming like a sci-fi phantom, a gossamer, spaceship-like car floats in the mercurial light of Center Galleries. It is an actual sized sculpture of the 1958 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz– framed with resin and then shrouded in white, embossed Bounty paper towel–and is the fabrication of New York artist Will Ryman. The thing astonishes with its implausibility. We in Detroit wait every year for the latest and greatest version of automobiles but this particular moment, 1958, called for something different.

Will Ryman, 1958 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz, Wood, Resin, Paper towel, 2017

Post World War II life is often referred to as the moment when America was great, as in “Make America Great Again.” The United States had emerged from WW ll as a savior of the Western World and the soldiers returned to an explosive economy that inspired and encouraged a new and better life. The soldiers got the GI Bill which was money for fighting the war. The brilliant technologies developed to build planes, ships, tanks, and guns were ready to be employed to build a new American infrastructure. After a few post war years of stagnant auto sales, Harley Earl, head of General Motor’s “Styling Department,” employing a strategy called Planned Obsolescence, found a way of making a new car, an alluring “object of desire,” every year and one for every purse. It was a very big deal! From Chevy, Pontiac, Buick, Oldsmobile to Cadillac every American wage earner could have a car that represented their class and level of economic status. The cars slowly evolved with modest cosmetic changes every year—a curve of a fender here, a piece of chrome there, a new palette of tantalizing colors, sumptuous upholstery or push button radios with front and rear speakers. Each new year model made last year’s version less attractive, less sexy. The American economy was the wonder of the world.

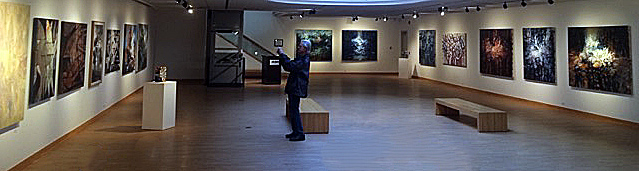

Will Ryman, Installation image, all images courtesy of Robert Hensleigh

The 1958 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz, a hybrid of the P-38 fighter plane, a horse drawn carriage of the Victorian aristocracy and avatar of female goddess, was at the top of the heap. Its name says it: three names all denoting power and wealth– Cadillac for the historical founder of Detroit; Eldorado, Spanish for gold and the lost city of gold in Spanish mythology; Biarritz the French resort on Basque coast made famous by actress Bridget Bardot and the hangout of the very rich.

Will Ryman (b.1969), playwright, sculptor, painter, and, conceptual artist, has most recently composed what seems like a trilogy of poignant installation/sculptures that turn on American politics and history, culture and identity. Each uses apt materials to perform dramatic vignettes focusing attention on the collision of American ideals. Ryman’s “America,” (2013) is an actual-sized model of Abraham Lincoln’s boyhood home and is now housed in the New Orleans Museum of Art’s permanent collection. The cabin is made of real logs but coated with a rich gold resin patina and has an interior brimming with tesserae of bits that compose the history of American labor and production. The interior walls are a mosaic of everything from cottons balls and slavery shackles to pills, bullets, iPhones and arrowheads.

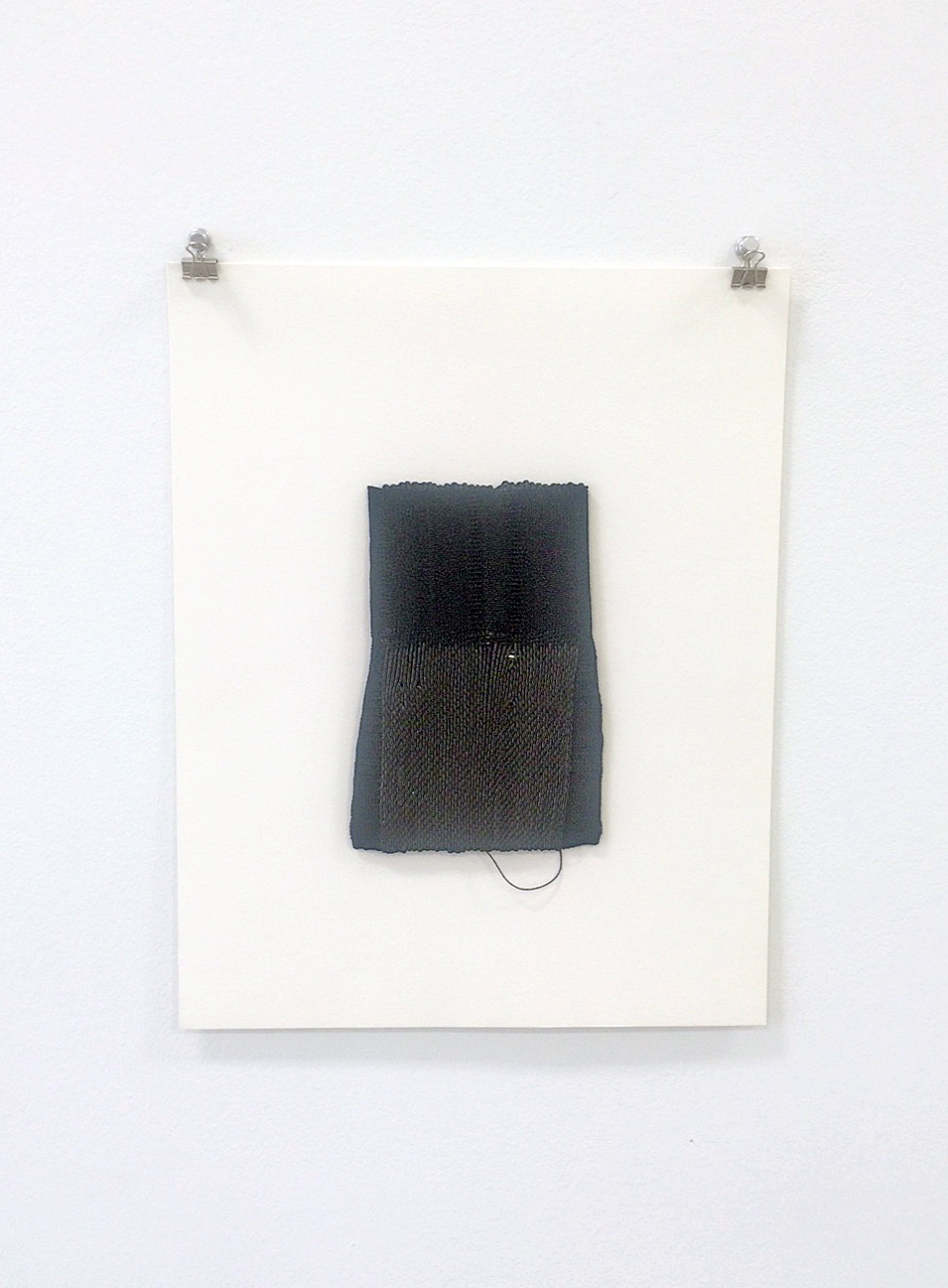

Will Ryman, The Situation Room, 2012 – 2015

More contemporary and polemic is Ryman’s “The Situation Room,” (2012-14) a life-size sculpted tableau of the famous and bizarre photo of President Obama and his closest circle, including Hillary Clinton, watching a live-feed from Pakistan of the assassination of Osama bin Laden by Navy Seals. Appropriately composed of crushed coal, turning the tableau into a shadow in the American memory bank, it serves as frightening meditation on the all too intimate scale of war and global politics. Perhaps because he was a playwright, Ryman’s sense of history and drama are dead-on as he seems to choose subjects and materials that point poignantly at the vital issues of our culture. Few artists of our time have been able to deal so directly with our political landscape.

Will Ryman, Detail, 1958 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz, 2017

“Cadillac” (2014) is a haunting installation that, as you spend time with it, accumulates gravity and puts American history in strange relief. Beyond its initial novelty, a mashup of art history with its winged tailfins, sculpted with Art Nouveau’s whiplash fender lines and wraparound windshield, bounteous breast shaped bumper guards and covered in Bounty paper toweling, it possesses an uncanny, funereal presence. Like the painted white ghost bikes along the side of the road that memorialize children being killed by cars, “Cadillac” summons bigger thoughts about life and mortality and our collision with the industrial landscape. Bounty toweling, with its art deco (the symbol of cosmetic superficiality) embossed pattern and tag of “Bounty” on every sheet, creates an ironic commentary on the excesses of corporate America that was called attention to by President Eisenhower in his Farewell Address (1961). He warned of the threat of the Military Industrial complex that had taken over American culture and industry and that has become a part of everyday life.

The 1958 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz broke every rule and standard of “Good Design” (a phrase that also meant good economics) set by most thoughtful modernists. While car design became a form of pop culture and post war novelty and spectacle, American design had become ostentatious, superficial, a symbol of conspicuous consumption and in the long run bad economically. In 2017 it is a ghostly reminder and presence incarnating all of the worst impulses of American culture and economics and not simply a kitschy tableau. Ryman’s chimera of our past absorbs (“Bounty is the thicker, quicker picker-upper”) and exudes our strange history. Ryman recently said that, instead of editorializing on his art, he has learned to let his materials speak for themselves and his “Cadillac” Eldorado Biarritz is stunningly articulate.

As part of the current Center Galleries exhibition Alumni & Faculty Hall is exhibiting Jeff Cancelosi: Picturing Us, featuring engaging, large format color photos of some familiar faces of artists and prime suspects of the landscape of Detroit art.

Jeff Cancelosi, “Artist Bailey Scieszka” Photograph, 2016

CCS Center Galleries – Will Ryman: Cadillac – January 28-March 4, 2017