The new director of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), Salvador Salort-Pons, took the podium and introduced the new 30 Americans exhibition with relaxed confidence. The selection and planning for this exhibition had begun more than a year ago when he was head of the European Department at the DIA since 2008. With a Ph.D. in art history and a MBA with a focus on finance and strategy, he comes to the museum directorship with an additional strength: sound business sense. His time at the podium was brief, but I sensed a transitional moment for the museum and the larger Detroit community.

30 Americans is an important exhibition, extremely well curated, designed, and at the right place and time for the City of Detroit. It reminded me of how I felt at the opening of the Shirin Neshat exhibition, March 2013, when the DIA hosted her mid-career retrospective and simultaneously reached out to the community, educating people on Islamic art. 30 Americans is similar in how it will educate the Detroit community by showcasing some of the most talented African-American artists in the United States today. In the 2010 census, 82% of people living in Detroit responded as African American.

“30 Americans powerfully demonstrates contemporary African American artists’ interests in the complexities of identity and developing a range of artistic approaches to portray or reference its distinctions and similarities,” said Valerie J. Mercer, DIA curator.

The exhibition comes from the well-known Rubell Family Museum in Miami, Florida. It is one of the world’s largest, privately-owned Contemporary Art collections, and the first time this work will be on display at the DIA. Each year, Rubell creates thematic exhibitions drawn from its collection, “We only show art we own. That is a founding principle of the Rubell Family Collection, a principle that gives us tremendous freedom and enormous constraints. When we set out to conceptualize a new exhibition, we know we will only get the depth and quality we seek if we already have a strong foundation of works by a core group of artists.”

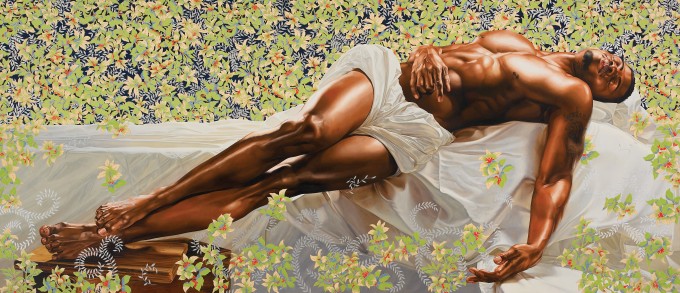

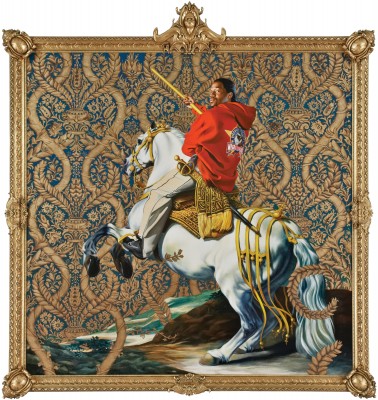

Kehinde Wiley, Equestrian Portrait of the Count Duke Olivares – 2005, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Rubell Family Collection, Miami

The most well-known artist in the exhibition is Kehinde Wiley, whose work dominates the show with three large paintings. The painting, Equestrian Portrait of the Count Duke Olivares, depicts a young black male figure in hip-hop clothing, set against a rich floral background. Based on the Spanish artist Diego Velazquez’s painting from 1634, Wiley engages in a type of surreal photorealism on a grand scale of 366 by 366 inches. He braids his foreground and background together, creating a picture plane tension. As a boy growing up in Los Angeles, he spent his time looking at historical paintings at the Library in San Marino, CA. He earned his undergraduate degree from San Francisco Art Institute and his M.F.A. from Yale in 2001.

As you enter the second room, you are met with Sleep, a 132 X 300-inch monster-sized figure painting, part of his series of reclining erotic figures. Here again, his use of British Arts & Crafts designs in the background also enters the foreground in what has become a consistent element in his work. At times, it reminds me of paintings of Christ after he was taken down from the cross. Wiley’s signature portraits of street people designed around specific historical paintings seem to draw attention to the absence of African American people from Western cultural narratives. Like this work or not, he is a major force in contemporary art in American painting today.

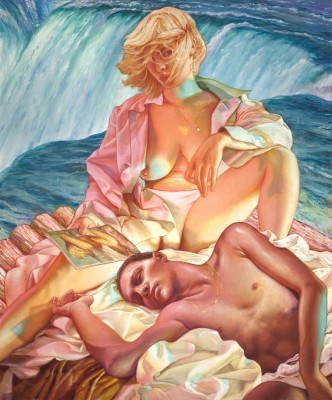

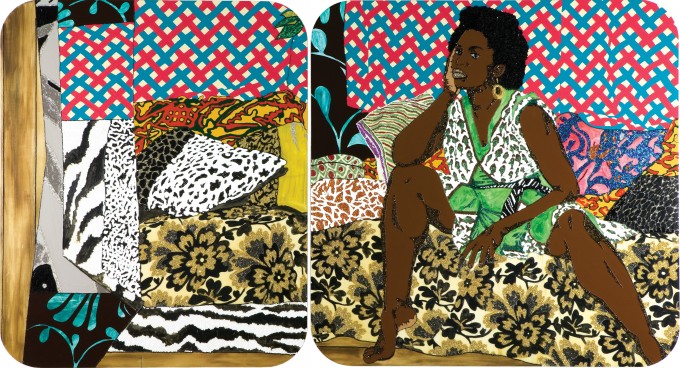

Mickalene Thomas, Baby I Am Ready Now – 2007, acrylic, rhinestone and enamel on wooden panel. Courtesy of Rubell Family Collection, Miami

The irrepressible Mickalene Thomas is comparable to Wiley in her weight and influence on the American art scene. The New York-based artist is known for her elaborate and complex work that often has a sexual overtone. She may be presenting what she thinks it means to be a black woman regarding a kind of cultural stereotype. The paintings are often composed using patterns, enamels, acrylic, and rhinestones and usually present a provocation. Her painting, along with the title, seems to bait the viewer. These round corners were a favorite of hers back in the mid 2000’s, but the new work has moved forward with a kind of spin on Picasso’s figurative Cubism. Check out: She Ain’t a Child Anymore #2, 2015.

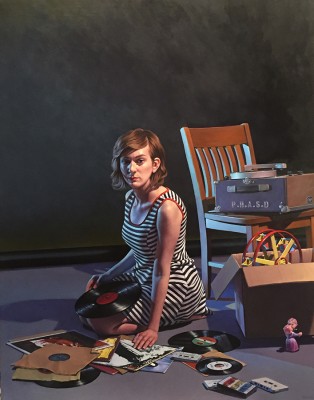

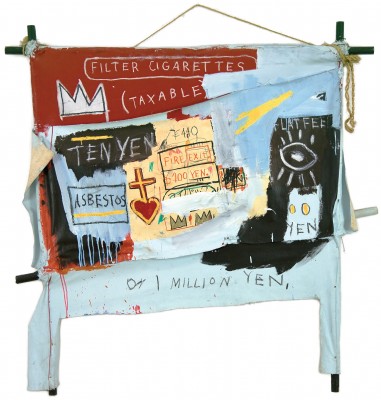

Jean-Michel Basquiat, One Million Yen – 1982, oil on canvas with wood and jute. Courtesy of Rubell Family Collection, Miami

More familiar to audiences is Jean-Michel Basquiat. The late American artist achieved notoriety during the 1980s when he was part of the Andy Warhol and Keith Haring scene in New York City. Born in Brooklyn, Basquiat was half Puerto Rican and half Haitian and has been described as a precocious and gifted child. Kellie Jones, who wrote Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re) Mix says, “Basquiat’s cannon revolves around single heroic figures: athletes, prophets, warriors, cops musicians, kings, and the artist himself. In these images the head is often a central focus, topped by crowns, hats and halos. In this way the intellect is emphasized, lifted up to notice, privilege over the body and physicality of these figures (i.e. black men) commonly represented in the world.”

The Rubell piece, One Million Yen, from 1982 creates one of his “dichotomies” utilizing social commentary that attacks a power structure, while at the same time imparting a strong Neo-expressionist composition using mixed media material.

The exhibition is peppered with work by a variety of African-American artists that speaks directly to racial violence in the United States. When you enter the room housing the Duck, Duck, Noose piece by Gary Simmons, 1992, you are confronted by emotional experience where nine stools are arranged in a circle with KKK hoods on the seat with a noose hanging down in the center. The life-sized installation capitalizes on the audience’s familiarity with these symbols, reminding us of our historical past where injustices were committed against black men and women in the late 19th and mid 20th centuries. The title is a play on the English nursery game, Duck, Duck, Goose. The installation brings into focus the injustices that are continually committed against all peoples and through a juxtaposition of history where art imitates life. Gary Simmons’ work is currently representing the United States at the 2015 Venice Biennale.

30 Americans exhibits 55 paintings by artists such as Barkley Hendricks, Kerry James Marshall, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson and the late Robert Colescott. Their influence on a younger generation can be seen in the works of artists such as Nick Cave and Kara Walker. Overall, the exhibition reflects a variety of approaches to creating artwork around identity, gender, race, sexuality and a confrontation to the traditional American genres.

Bravo to the DIA for bringing this exhibition to Detroit…now what’s next? A big contemporary exhibition? As soon as there is a curator.

The Detroit Institute of Arts 5200 Woodward Ave. Detroit, Michigan 48202 313.833.7900

For information about admission pricing, and hours: http://goo.gl/OJU15N