An installation photo of How We Make the Planet Move: The Detroit Collection Part 1 at Cranbrook Art Museum through March 2, 2025 (Courtesy Cranbrook Museum of Art, PD Rearick; subsequent photos by Detroit Art Review).

There was a time, decades ago, when Cranbrook held itself at a careful remove from the city of Detroit, only 18 miles distant, but light years away. Anne Morrow Lindbergh, who spent two happy years in the early forties at the Academy of Art while Charles helped Henry Ford convert the Willow Run plant from auto to bomber production, called it “the Ivory Tower sitting on the outside of the volcano of Detroit.”

In recent years, that relationship changed dramatically – a shift epitomized by the current exhibition, How We Make the Planet Move: The Detroit Collection I, at Cranbrook Art Museum through March 2. The museum has been energetically acquiring art by contemporary Detroit artists, and since 2014 has amassed over 300 works, of which 30-odd are currently on display. The show includes young artists like Sherri Bryant and Matthew Angelo Harrison, as well as the late, beloved Gilda Snowden, and Cass Corridor greats Michael Luchs, Nancy Mitchnick and Gordon Newton. “This was a substantial gear shift in our focus,” said chief curator Laura Mott, “to be a storyteller of Detroit art, and I think that’s an important role.”

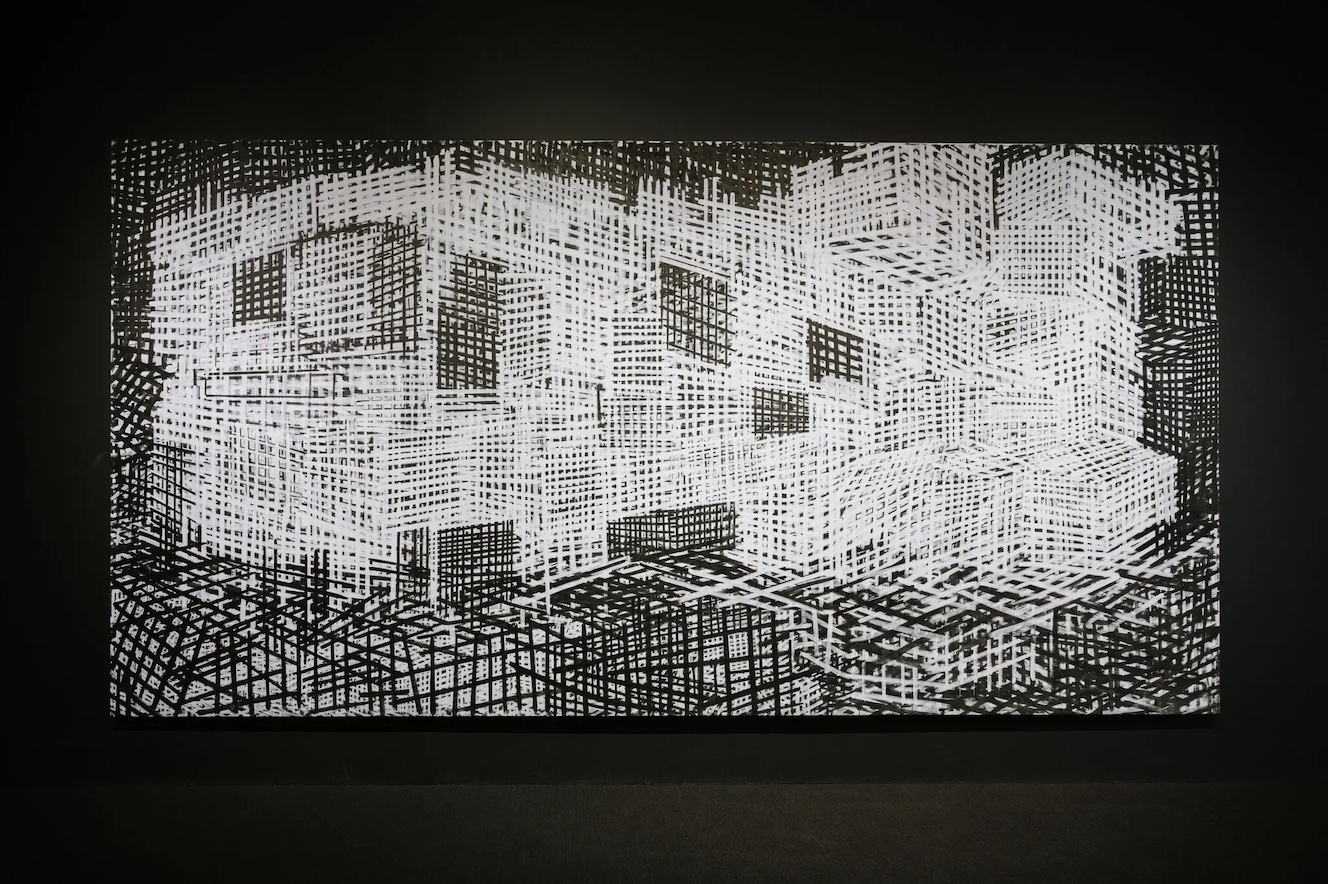

Charles McGee, Play Patterns II, Fabrics, paper, the artist’s hair, paint and enamel on Dibond attached to wood frame, 120 x 240 inches, 2011.

Their biggest acquisition, both in price and size, was the late Charles McGee’s Play Patterns II from 2011, a dazzling, colorful canvas starring spindly, hieroglyph-like figures that’s a close cousin to the artist’s 1984 Noah’s Ark: Genesis at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Over an 80-year career, McGee – named the Kresge Foundation’s first Eminent Artist in 2008 – produced a mountain of work ranging from the severely geometric to idiosyncratic figurative portraits and highly stylized abstractions, both in painting and sculpture, that formed much of his later work. A good example of the latter is the black-and-white United We Stand outside the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. McGee died in 2021 at 96.

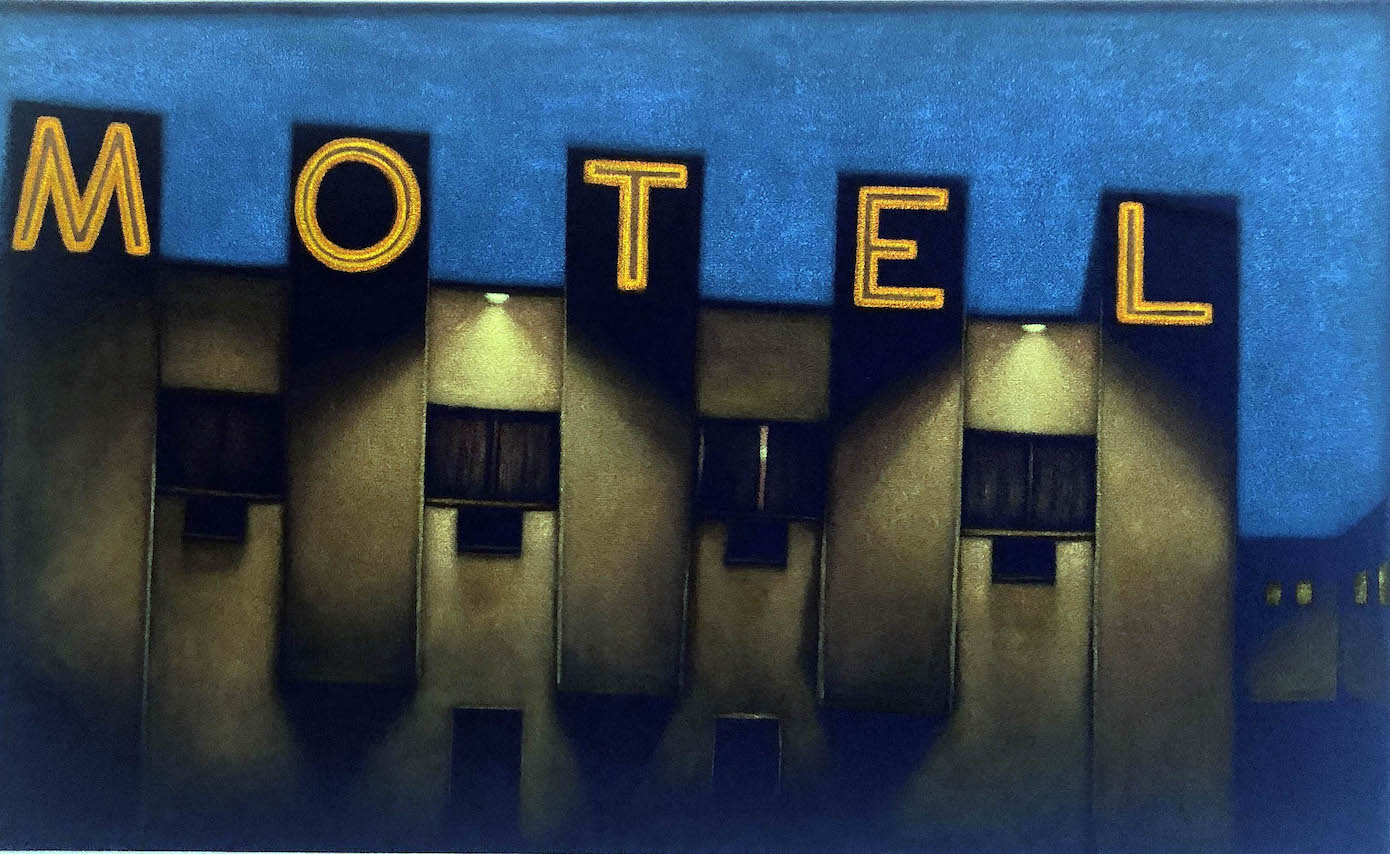

Joshua Rainer, The Flying Dream, Oil on canvas, 46 x 102 inches, 2023.

Mott says she first included a painting by Joshua Rainer at the Art Museum in Skilled Labor: Black Realism in Detroit, which closed last March, without knowing that he was an Art Academy student. Indeed, he’s the first enrolled student to appear in a non-student exhibition at the museum. Mott says artist Mario Moore, who co-curated Skilled Labor with her, “calls Rainer ’the human printer’ because his skill level is insane,” noting that the portrait of his grandmother in Skilled Labor was often mistaken for a photograph.

Rainer’s piece in Detroit Collection is The Flying Dream. It’s less photo-realistic and moodier, an evocatively colored work in grayish pinks and dull orange, in which a body – presumably the artist – is suspended horizontally in mid-air, face down. The unexpected hues give it an undeniable dream-like quality, an image halfway between believable and hallucinatory. But in ways that are hard to explain, the painting’s dominant impression is one of a profound, mesmerizing stillness.

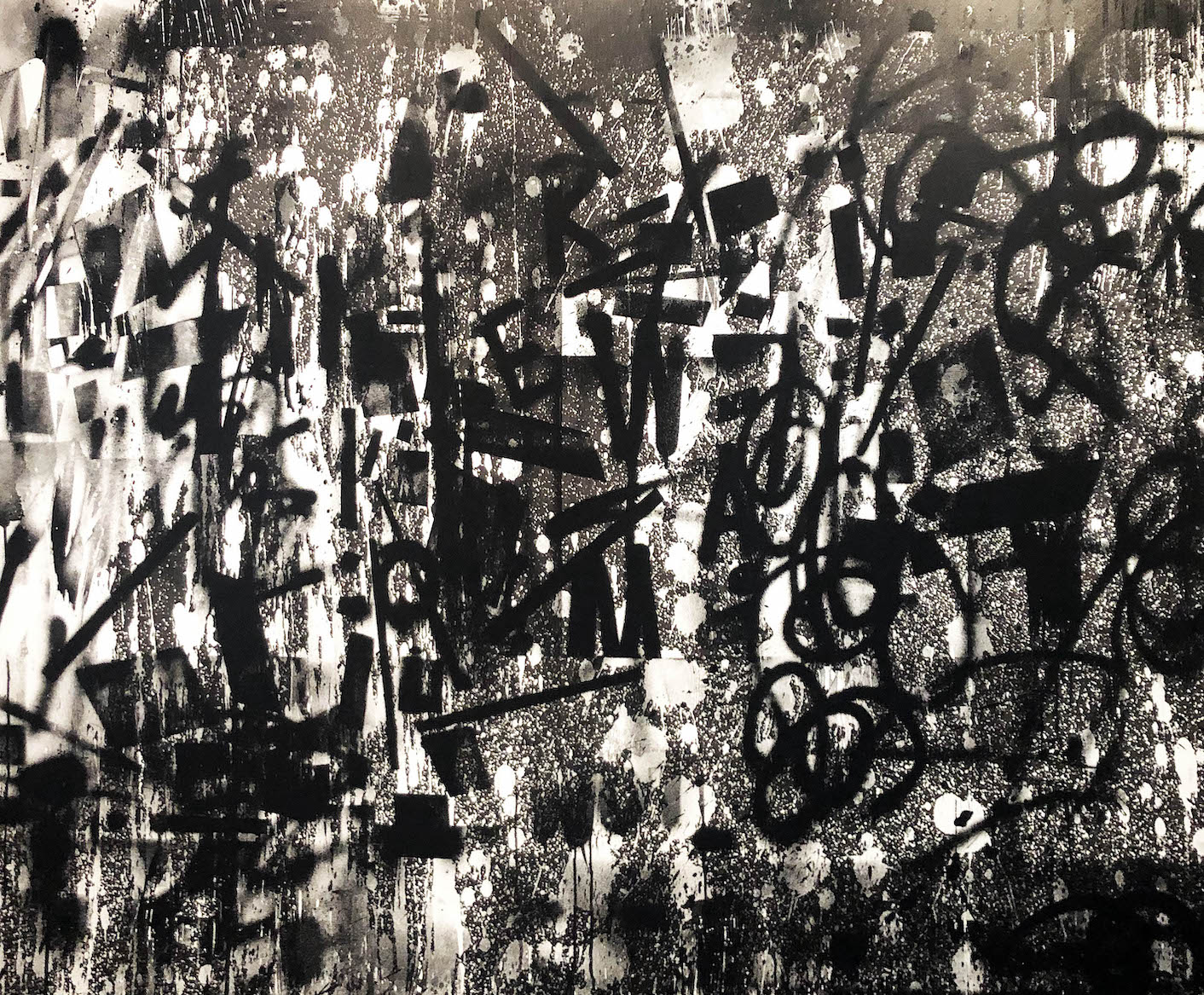

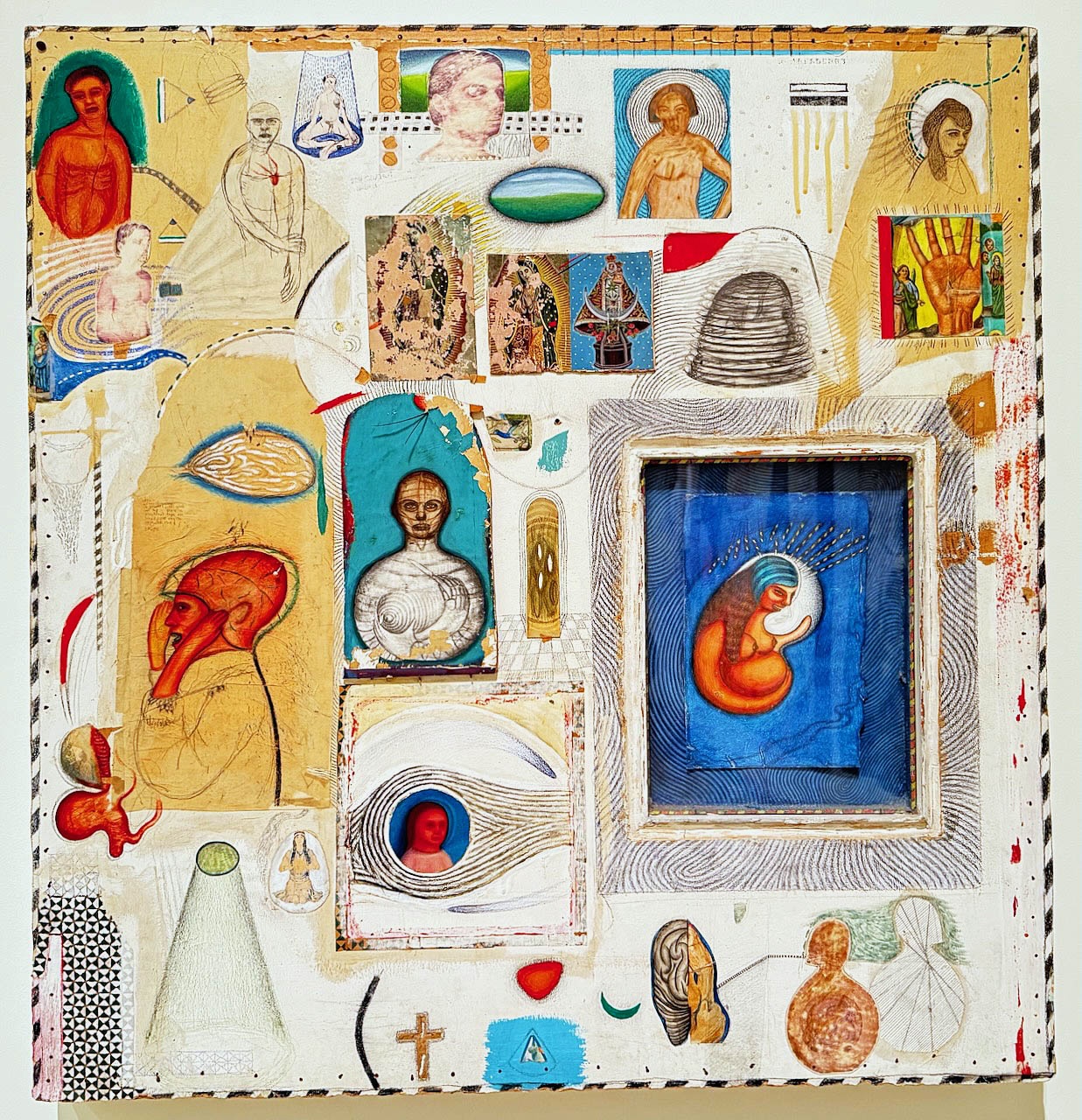

Ed Fraga, 229 Gratiot, 35 x 35 x 3 inches, 1986.

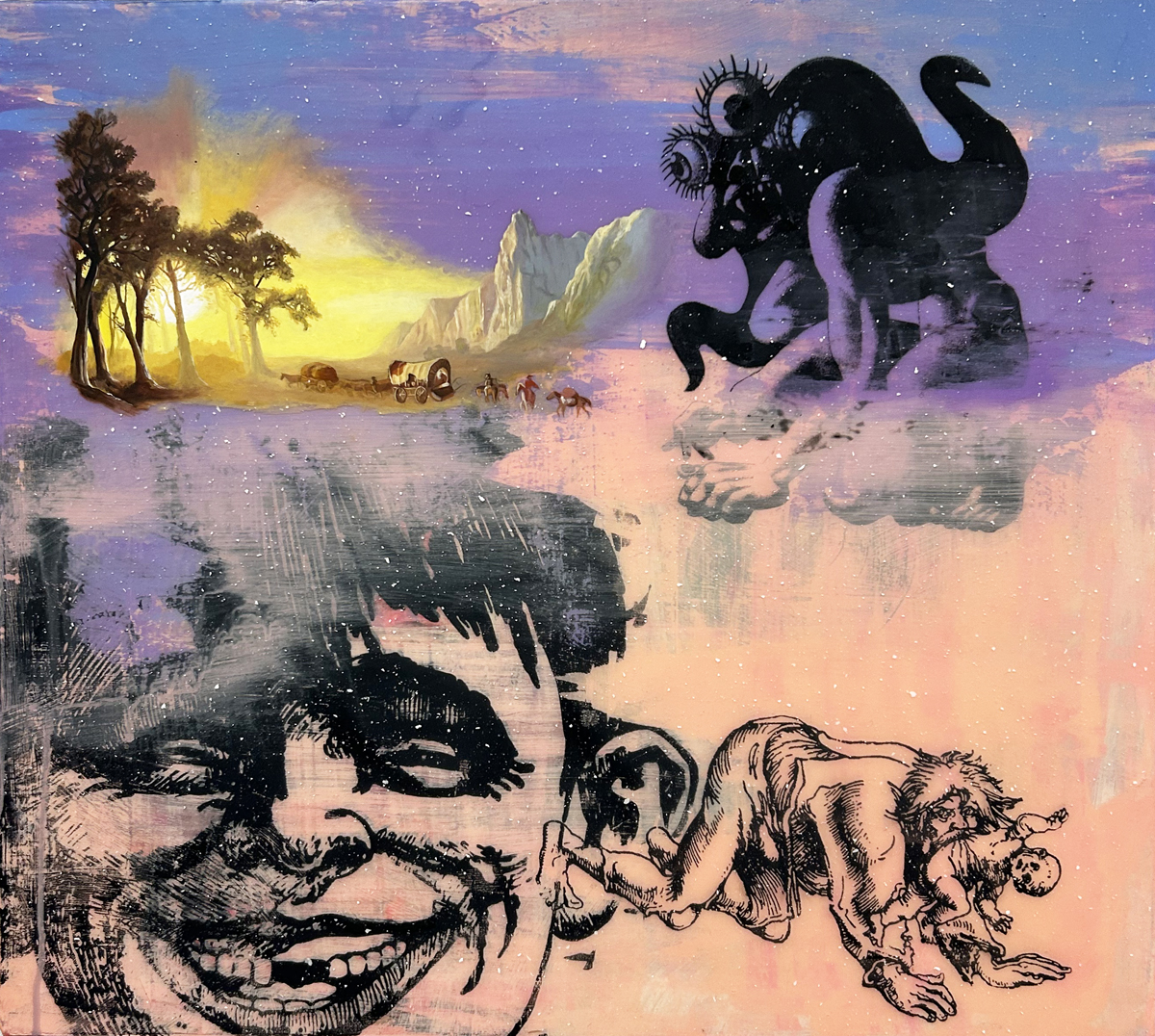

Ed Fraga, a 2009 Kresge Artist Fellow, has produced a rich oeuvre that mostly wanders the subconscious, delving both into the psychological and the spiritual, with results that are enigmatic yet oddly beguiling. In considering the Wayne State University grad’s relationship to his audience, Steve Panton in Essay’d speculated that, “Perhaps at times it is closer to the artist as magician, encouraging the viewer to suspend disbelief, and see more mystery in the world.”

“Mysterious” is certainly the word for 229 Gratiot, a collection of small portraits a bit like a whimsical two-dimensional closet of curiosities. They range from an apparent saint whose halo divides into concentric circles, a luminous female fetus floating on an azure square, a palm bearing stigmata, and a tiny cameo of the kneeling Land-o-Lakes butter maiden. Typical of much of Fraga’s work, it’s a bit dizzying and elusive but an awful lot of fun to study.

Jack Craig, Molded Carpet Chair, Green; Molded carpet, wood, fabric; 32 x 22.5 x 21 inches, 2024.

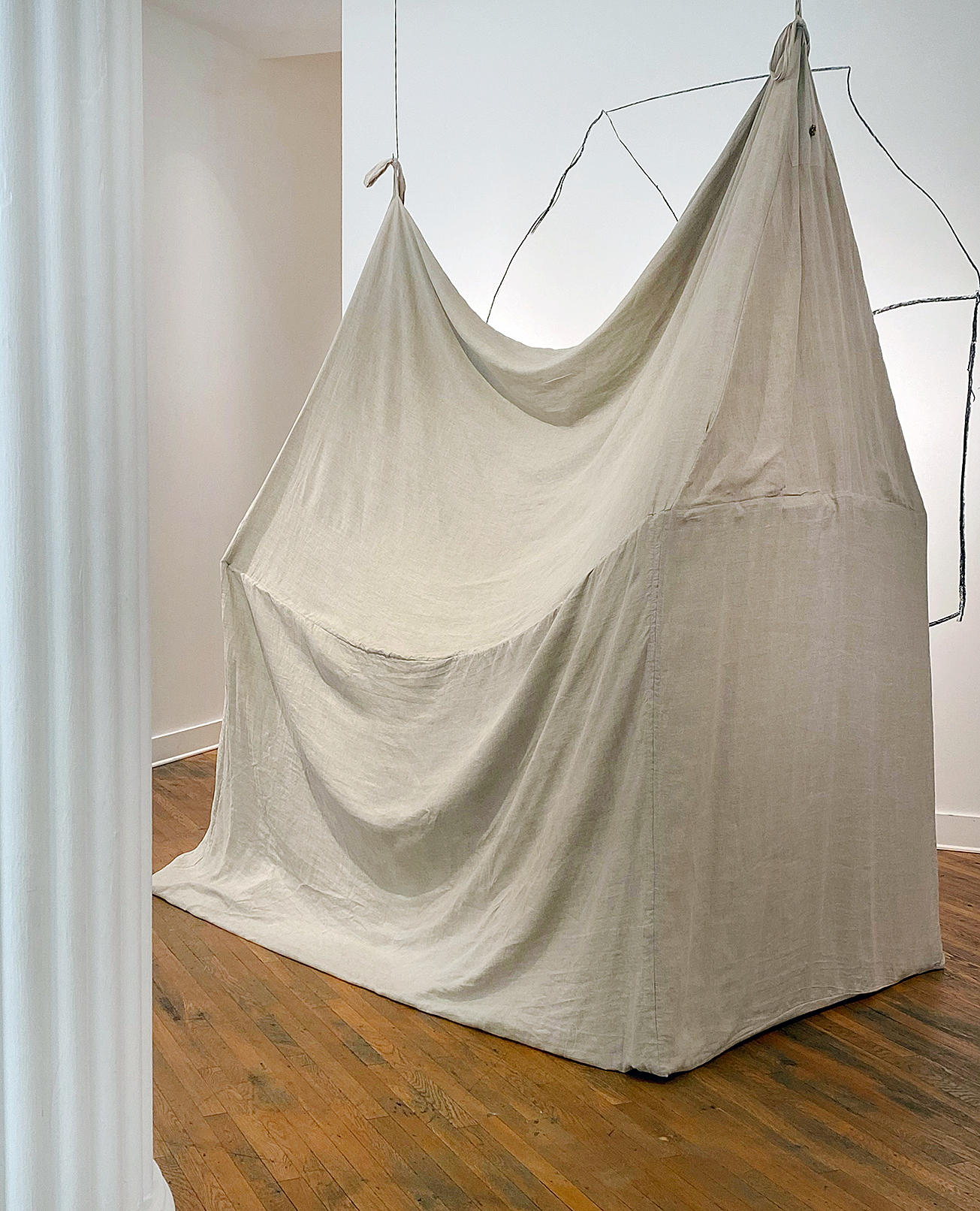

Leaping genres, one creative endeavor the Academy of Art has always been known for is chair design, starting with Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames’ molded plywood chairs that took first place for seating in the 1941 Organic Design for Home Furnishings competition at the Museum of Modern Art. Along with other Academy designers of that era like Ralph Rapson, Florence Knoll and Harry Weese, Cranbrook’s output revolutionized the look of the American home and office, and made U.S. modernist design a world leader.

Continuing that grand tradition, but giving it a more artsy, less functional, spin is Jack Craig’s Molded Carpet Chair, Green, which was also exhibited at the David Klein Gallery in a solo show that closed in October, and included a number of other phantasmagorical pieces. Mott notes that the early Eames and Saarinen works went into commercial production, but with recent Academy alumni like Craig and Chris Schanck, “you see more of an art design. Molded Carpet Chair is not going into production,” she said. “These are exquisitely made art objects that suggest function,” rather than exhibiting it. In the case of Molded Carpet Chair, the result is a lush object that feels more organic than structural, with all sorts of exuberant, textured excrescences sprouting on it.

A companion show on the Art Museum’s first floor is Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within, which runs until January 12, 2025. One of the world’s most-celebrated ceramicists, Takaezu died in 2011 and had a most-astonishing biography. Born into an impoverished Japanese immigrant family on a remote part of Maui, Takaezu was the sixth of 11 children and had to quit school at 15 to work as a housekeeper in Honolulu to help support her family. But luck was on her side – when the family left during World War II, she got a job at the Hawaiian Potters Guild. Ultimately, she studied ceramics part-time at the University of Hawaii at Manoa under Claude Horan, whom Takaezu called the father of Hawaiian ceramics.

Toshiko Takaezu, Light, Porcelain, 1970.

The turning point in Takaezu’s life came when she saw pieces by Maija Grotell, who was the head of ceramics at the Academy of Art. Never having traveled to the mainland, Takaezu made her way to Michigan, applied to Cranbrook, and got in. That not only supercharged and refined her touch with clay, but also started her on an academic path that landed her eventually at Princeton University, where she was a longtime professor and inspiration to generations of ceramicists.

Takaezu’s artistic genius spanned numerous genres. She not only worked in ceramics, but also weaving, painting, bronze casting and printmaking, displaying remarkable finesse in each. Part of the pleasure of this career retrospective, organized by The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York, is that there are examples from all these various disciplines on display.

But most remarkable are her signature creations, the “closed vessels,” like Light in the image above — essentially large pots that suggest a mouth or opening at the top but, on examination, turn out not to be there. This ability to both suggest a vessel while at the same time denying it is part of what gives the artist’s work its profundity. These pieces are, as the exhibition’s biographical panel notes, “abstract paintings in the round.”

Toshiko Takaezu, Gaea (Earth Mother), Stoneware, 1979-90.