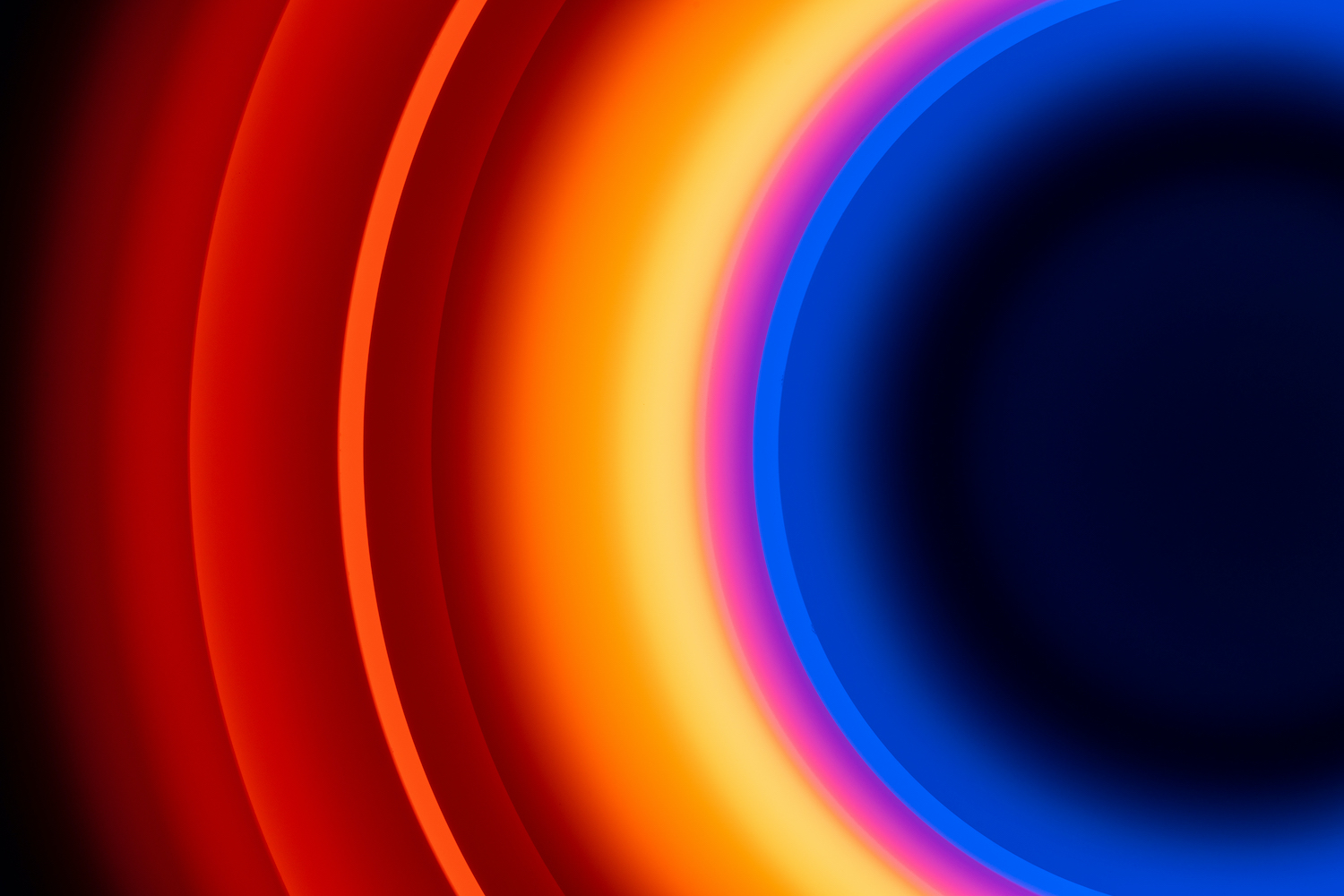

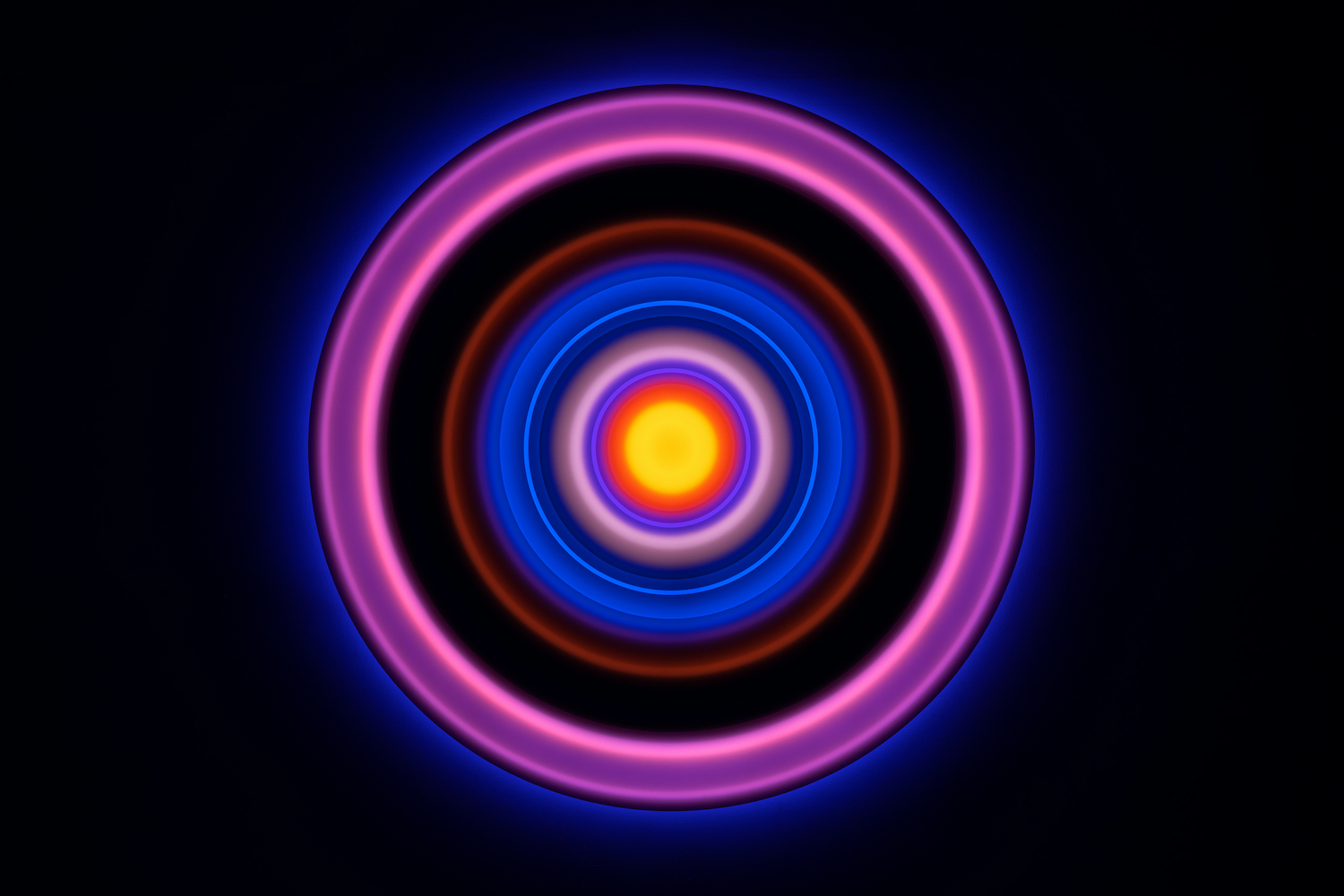

Phillip K. Smith III, Flat Torus 4. Photograph by Lance Gerber Studio

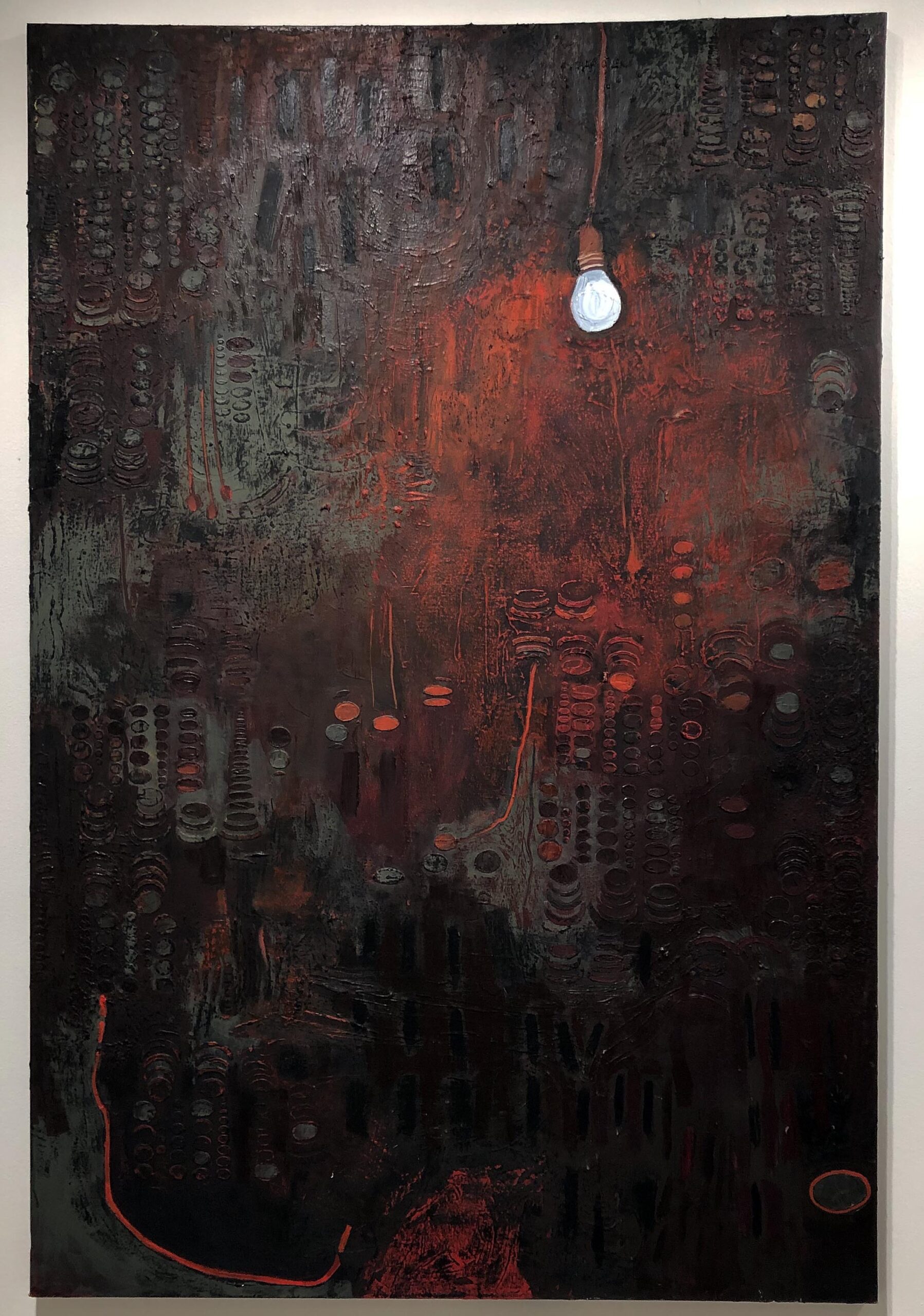

This year, the Toledo Museum of Art added to its permanent collection Flat Torus 4, an ethereal light installation by multimedia artist Phillip K. Smith III. This work is the visual anchor of the exhibit Luminous Visions. Concurrent with this single-gallery show is a sprawling retrospective of the stained glass art of Judith Schaechter. As different as these two exhibits are in form and content, they both directly engage with centuries of art history, they both take luminosity as their subject, and they’re both visually mesmerizing. As such, these two separate shows compliment each other like the varied notes of a musical chord.

The centerpiece of Luminous Visions is Flat Torus 4, a series of wall-mounted concentric rings which, with the aid of computer software and LED lights, moodily project diffused light into the gallery space. It’s an instillation which recalls the atmospheric light sculptures of Dan Flavin. Flat Torus 4 is tactfully placed in conversation with an ensemble of other works from the TMA’s collection which literally or metaphorically take light as their subject. These include a 19th Century painting by Sanford Robinson Gifford of Maine’s Mt. Katahdin, beautifully illuminated by a rising sun. And a 15th Century sculpture of a seated Buddha speaks to the metaphorical and spiritual associations of enlightenment and illumination. The works in this exhibit span nearly 700 years, but Flat Torus 4 is the undisputed star of the show; its soft light bathes the whole room in its shifting colors which slowly and satisfyingly cycle over the course of 40 minutes. This micro-show is an interesting and visually satisfying vignette, and it seems like great starting point for what could be a larger exhibition addressing light and illumination in art across the TMA’s collection.

Phillip K. Smith III, Flat Torus 4. Photograph by Lance Gerber Studio

In contrast to the stately serenity of Luminous Visions, the glass works on view in the traveling show Path to Paradise are loud, irreverent, uncomfortable, and often violent. Yet they’re also undeniably beautiful and cathartic. Glass artist Judith Schaechter takes her inspiration in equal parts from Northern Renaissance art and the aesthetics of Mad magazine. Through January 3, the TMA is showcasing forty of her works, supplemented with original sketchbooks brimming with preparatory drawings which offer behind-the-scenes access into Schaechter’s creative process. Path to Paradise is her first survey exhibition, and given the impressive scale and scope of her body of work, it seems like one that’s long overdue.

The Battle of Carnival and Lent, 2010-2011. Stained-glass panel, 56 x 56 in. Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, NY; Marion Stratton Gould Fund, Rosemary B. and James C. MacKenzie Fund, Joseph T. Simon Fund, R. T. Miller Fund and Bequest of Clara Trowbridge Wolfard by exchange, and funds from deaccessioning.

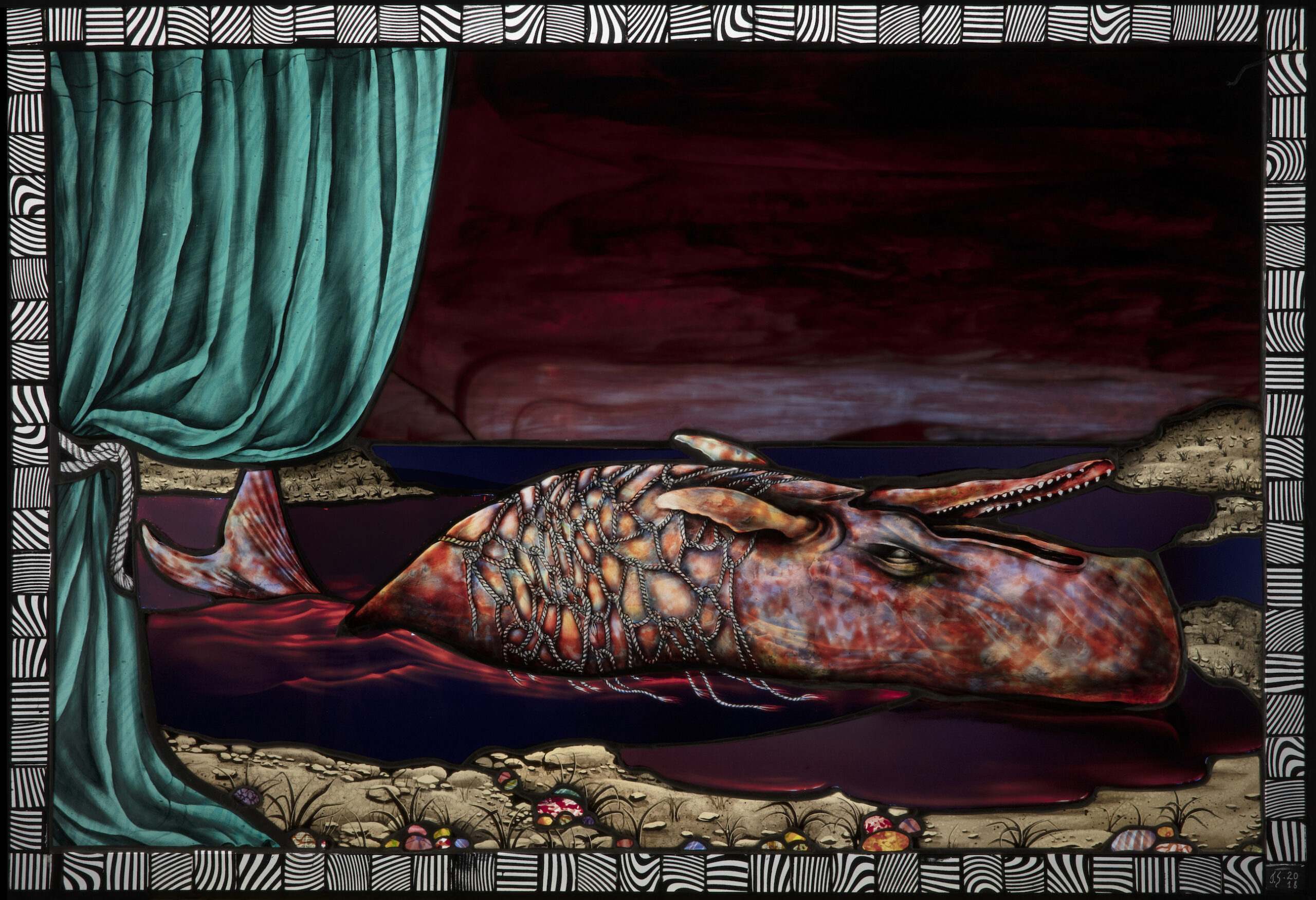

Beached Whale, 2018. Stained-glass panel, 27 x 40 in. Courtesy Claire Oliver Gallery, Harlem, and the artist.

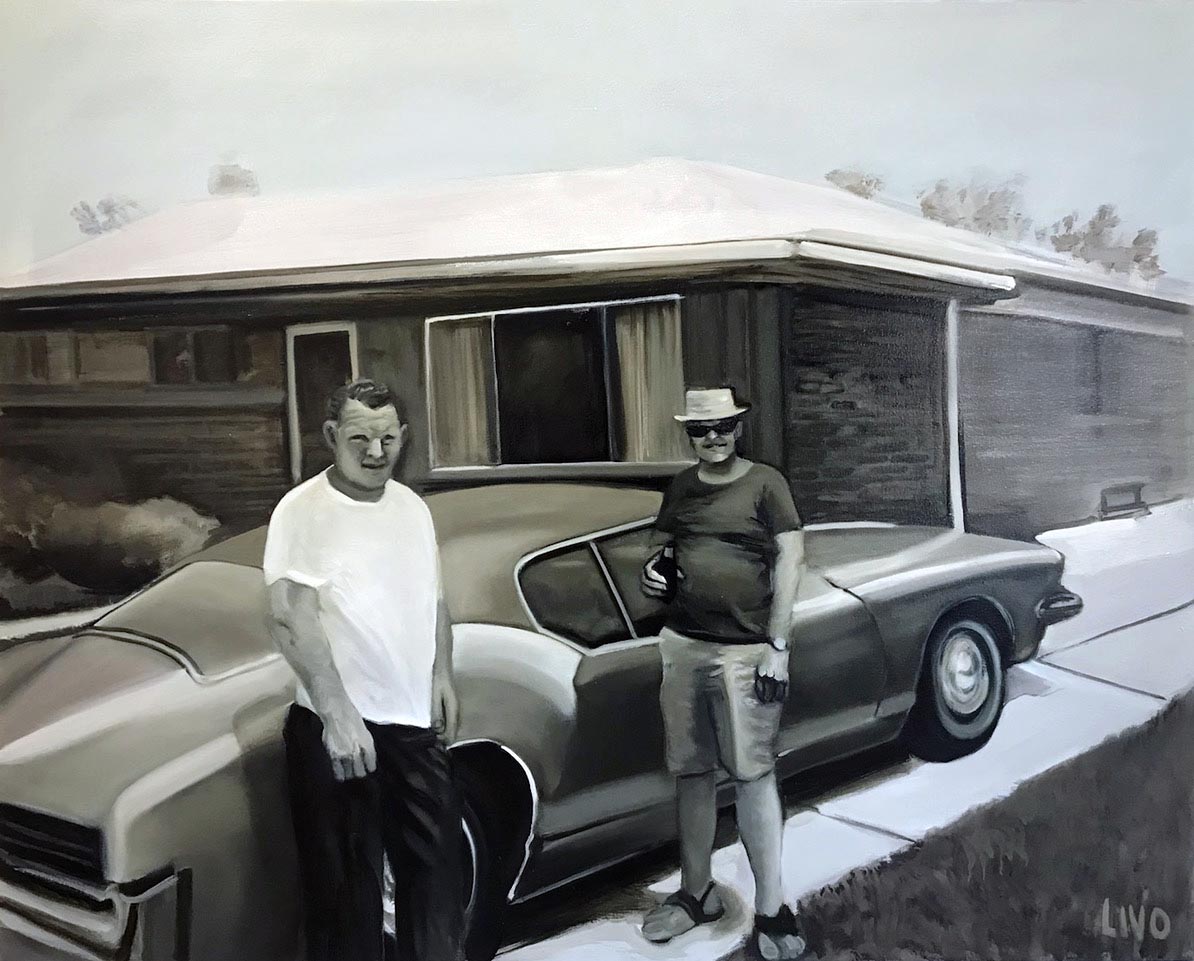

Schaechter manages to take a medium that reached its apex in the Gothic era and masterfully translate it into a 21st Century vocabulary. By applying a technique of layering glass which results in subtle gradients and shading, she lends her work a contemporary illustrative quality that you wouldn’t see in a 12th Century rose window. It’s a tedious process—each work takes months to complete– but much like the Old Masters of the Northern Renaissance, Schaechter delights in the details.

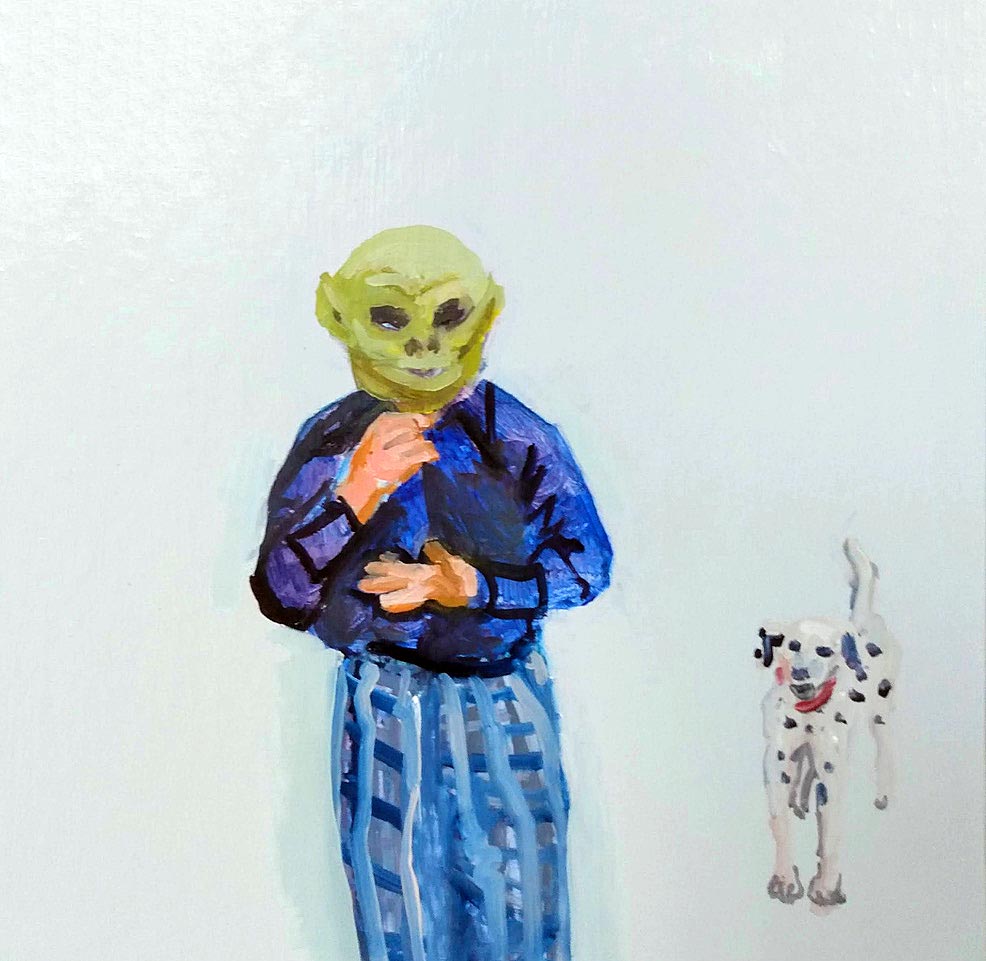

This show presents her earliest works in conversation with some of her most recent, surveying the trajectory of her career. Among these include The Flood, a triptych which thrust Schaechter into the national spotlight when it was displayed at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery when the artist was 29 years old. The figures that populate her fabricated worlds often seem caricatured, but she demonstrates an impressive ability to switch back and forth between cartoonish imagery and lucid realism, even within the same work. New or old, all her works are rendered with astonishing detail. In My One Desire, the background is teeming with plants, animals, and dazzling kaleidoscopic bursts of geometric patterns that snugly fill every bit of negative space, recalling a Renaissance tapestry. The work’s theme of a dying unicorn also situates this work in the tradition of Renaissance art, though the story here remains characteristically enigmatic. This horror vacui recurs frequently in her work. In A Play About Snakes, we encounter an elaborate pattern of twisting, writhing snakes that mimic the ornamental patterns found in medieval illuminated manuscripts– the Cross Page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, perhaps. Regardless of the subject matter, all her works teem with ebullient detail; no wonder she describes herself as a “militant ornamentalist.”

Although her work is often thematically dark, it can at times be playfully whimsical. Specimens shows a grid of various imaginary creatures preserved in little jars as if on display in a natural history museum; they seem plucked from the world of Hieronymus Bosch…or perhaps Dr. Seuss. And her improvisatory Exquisite Corpse is an homage to the silly party game of the same name which famously originated at the dinner parties thrown by Surrealism’s founder Andre Breton.

But much of Schaechter’s work is unsettling. We encounter many images of violence and death, a surprising number of which are actually sourced in Renaissance-era paintings and illustrations. Some of these works directly speak to recent and contemporary events. Sister is a disquietingly calm work in which the pose assumed by its lifeless subject references the haunting Vietnam-era photograph of the “Napalm Girl.” But within the work, this young girl inhabits indeterminate space, and Sister (much like Picasso’s Guernica) comes across as a universal statement against wartime atrocity which could apply to any time and any place. And in Emigration Policy, we see a dog drowning as it desperately tries to catch up with a departing ship (or was it thrown overboard?). The violence in her work is never gratuitous, but rather serves to encourage empathy and compassion on the part of the viewer.

The Floor, 2006. Stained-glass panel, 36 x 34 in. Collection of Claire Oliver

The subject matter of Schaechter’s work runs the gamut between agony and ecstasy, and is Shakespearian in its scope. As to the question of why her work is often so uncomfortable, Schaechter responds on her website with a passage excerpted from James Poniewozik essay The Art of Unhappiness: “What we forget…is that happiness is more than pleasure sans pain. The things that bring us the greatest joy carry the greatest potential for disappointment. Today, surrounded by promises of easy happiness, we need someone to tell us that it is O.K. not to be happy, that sadness makes happiness deeper.” Bearing this in mind, as uncomfortable as many of her works might make us, it seems that the body of her work is– in the final analysis—ultimately life-affirming in its unashamed embrace of the totality of the human experience.

The Path to Paradise: An Interview with Artist Judith Schaechter

Toledo Museum of Art – The Path to Paradise: Judith Schaechter’s Stained-Glass Art — Jan. 3, 2021 | Levis Gallery