Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped and McArthur Binion: Binion/Saarinen, opens at the Cranbrook Art Museum

Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped (installation view), 2017. Photo by Gary Zvonkovic. Courtesy the artist and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

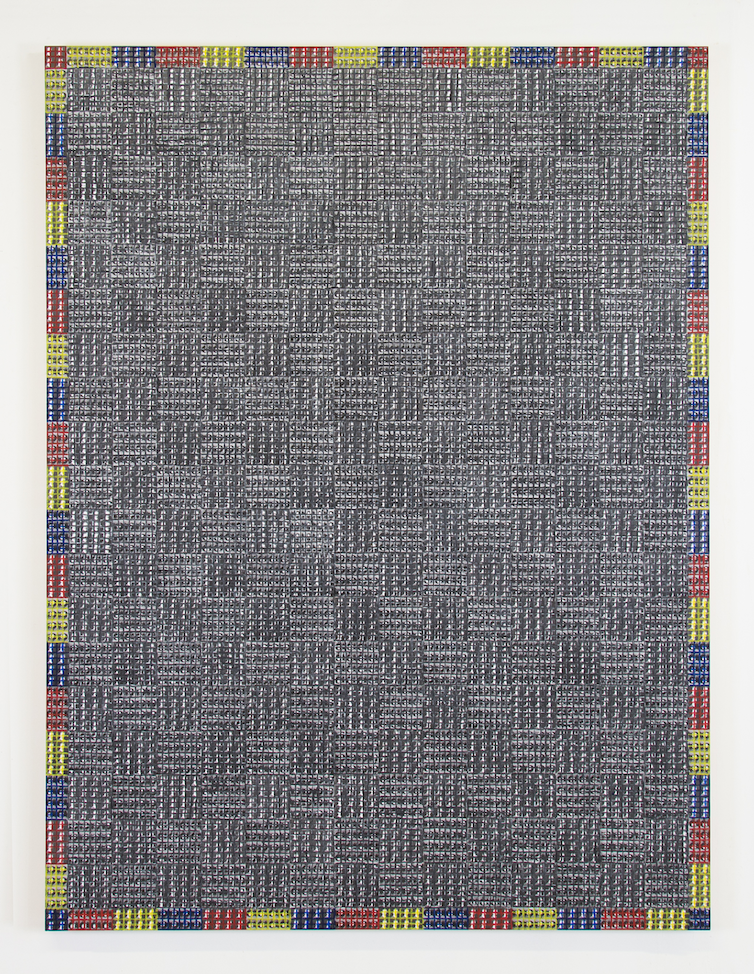

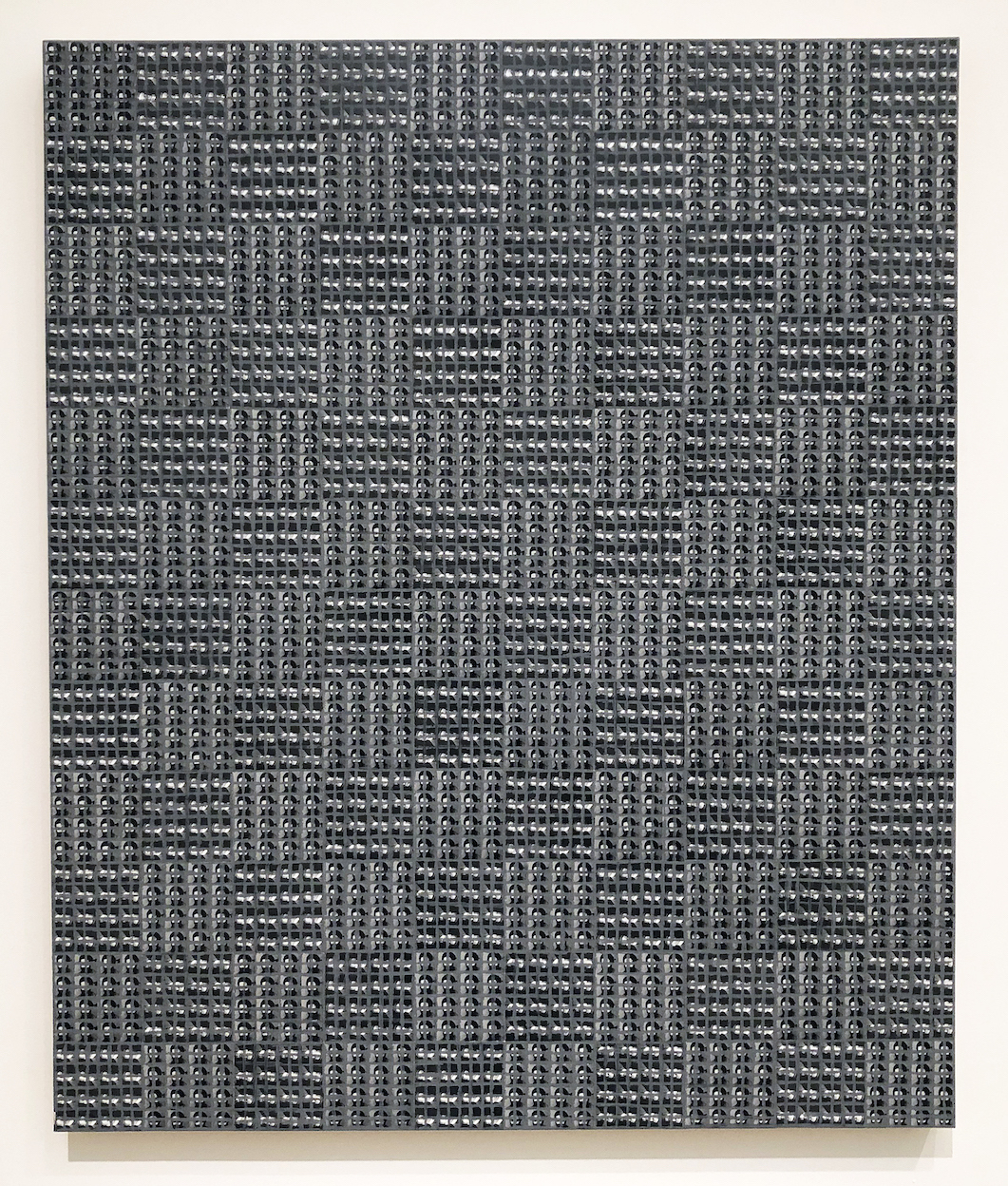

McArthur Binion, Binion/Saarinen: I, 2018, oil paint stick and paper on board, Courtesy Modern Ancient Brown

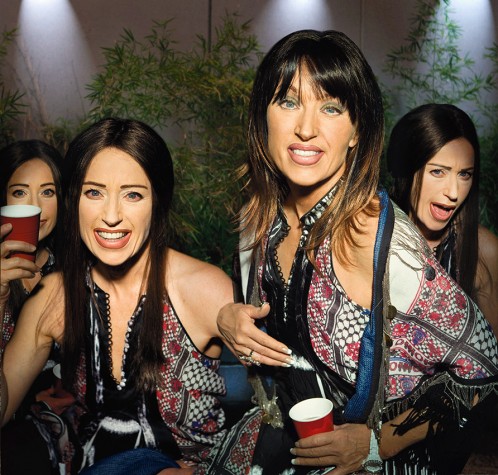

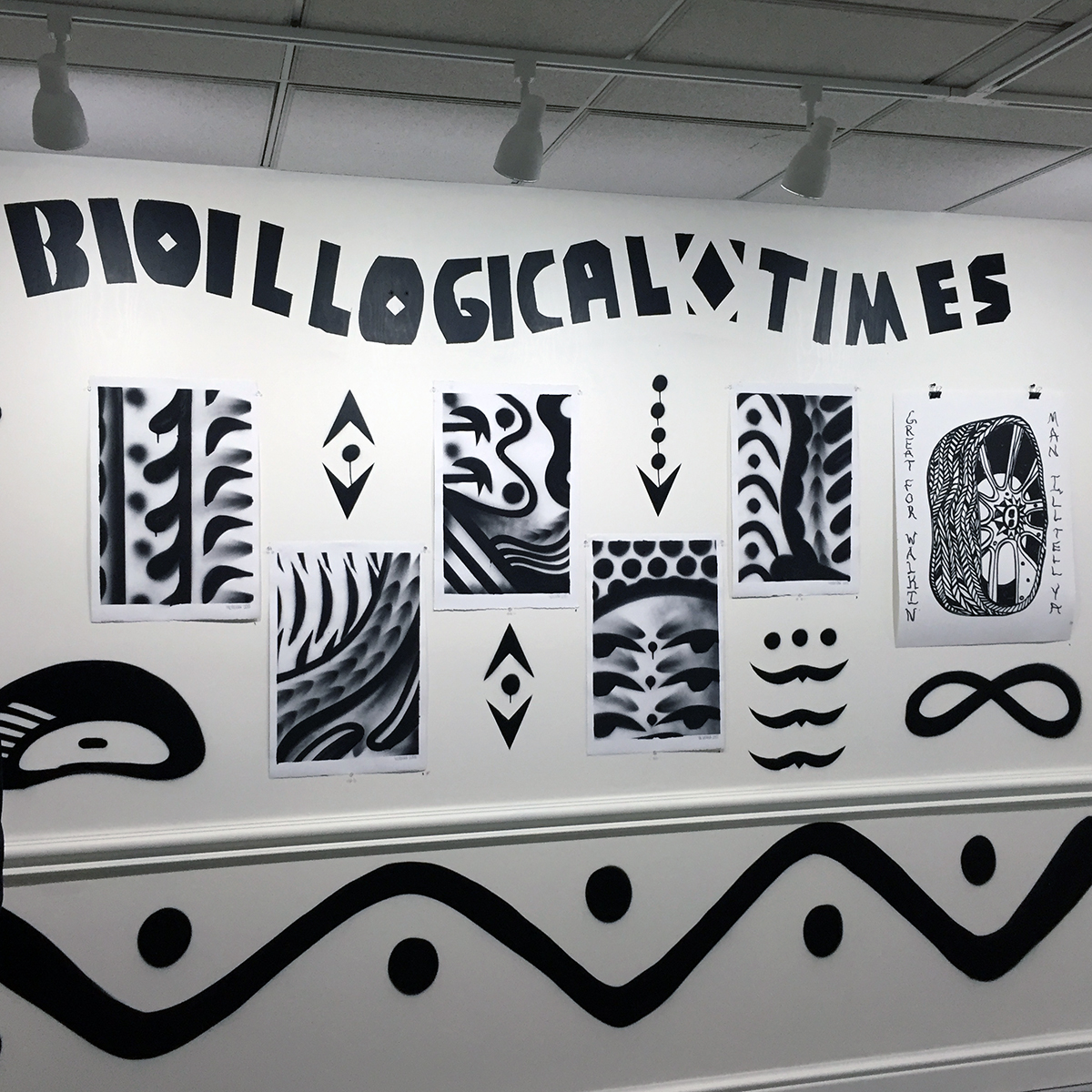

Two Cranbrook MFA graduates, Annabeth Rosen (81) and McArthur Binion (73), have returned to the Cranbrook campus at the Cranbrook Art Museum (CAM) as seasoned artists with exhibitions that provide a platform to exemplify their accomplishments. The exhibition opened November 17th, 2018 and runs to March 10, 2019, easily utilizing the spacious galleries, especially the Annabeth Rosen exhibit, which is nothing less than mammoth in its scope.

I’ve written about McArthur Binion before and seen his work representing the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2017, so when this exhibition first came to my attention, I assumed Binion would be my focus. But the exhibition of his work here at CAM is modest in comparison to the work of Rosen in both the Main and the Larson galleries. Her work is the artist’s first major museum survey that archives more than twenty years of work. A critically acclaimed pioneer in the field of ceramics, Rosen brings a deep knowledge of the material’s history and processes to the realm of contemporary art.

Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped (installation view), 2018. Photo by Detroit Art Review.

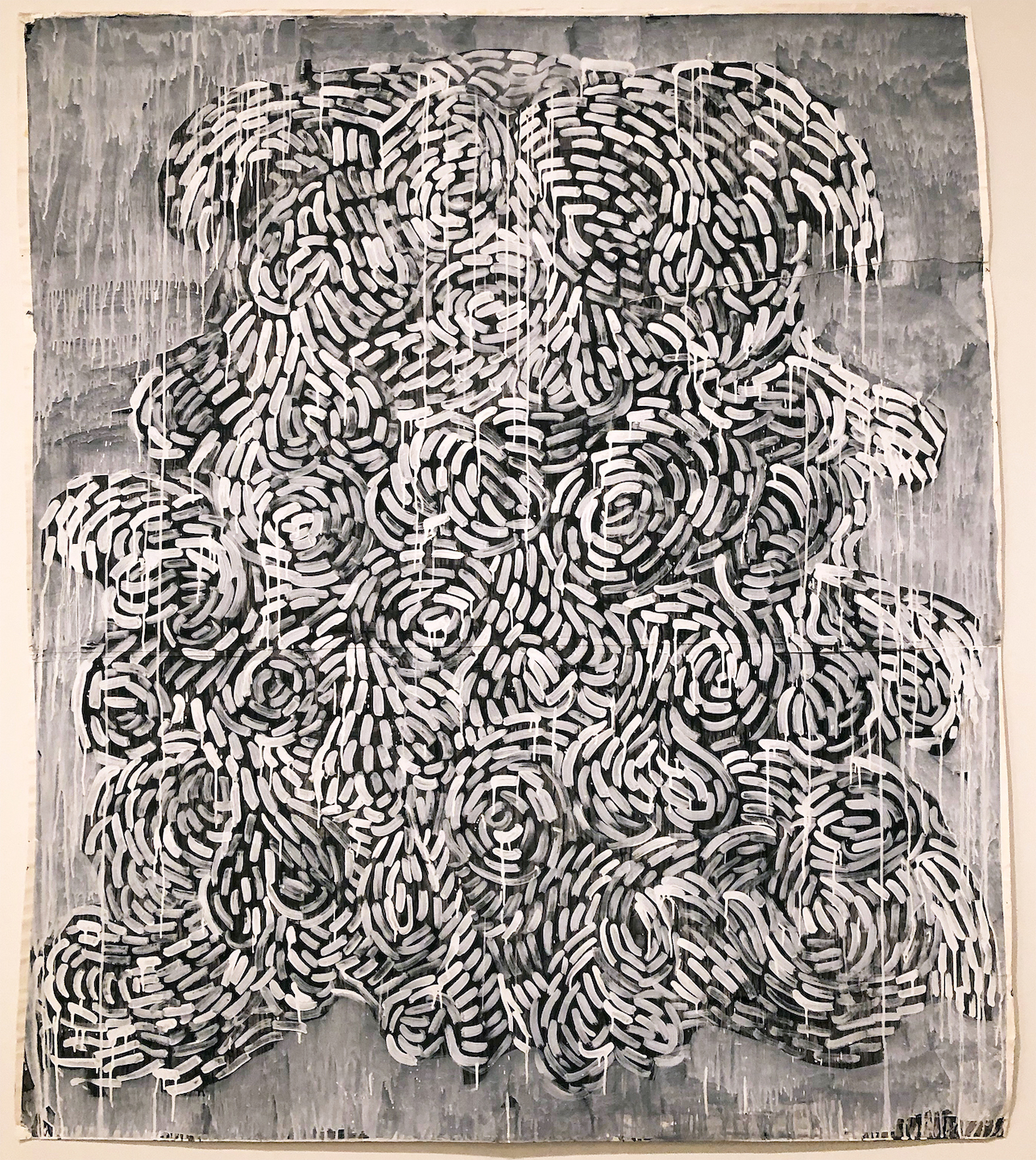

Rosen’s work is curated by Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston’s senior curator, Valerie Oliver, and surveys two decades of her ceramic additive work that has a derivative aspect found in abstract expressionistic art. Her studies at Cranbrook under Artist in Resident Jun Kaneko encouraged her to experiment with non-functional forms and separate her work from the traditional role of ceramics as functional craft. Much of Rosen’s work is assembled with already-fired broken parts which have been reassembled, re-glazed, and ultimately re-fired, adding wet clay to the process.

Rosen says, “I work with a hammer and chisel, and I think of the fired pieces as being as fluid and malleable as wet clay.”

Annabeth Rosen, Fired and glazed ceramic, Bundle, and rubber ties.

The ceramic work is divided up into categories: Mash Ups, Bundles, Mounds and Drawings. Some of the Mounds are bound together by wire, and others are smaller shapes (Bundles) that have been bound using rubber that might be made from a bicycle inner tube. Rosen began vertically stacking these bundles of ceramic and mounting them on a steel frame set on four wheels. Rosen has developed an acute interest in non-functional ceramic forms as abstract expressionistic sculpture along with painterly compositions of paint on paper.

Annabeth Rosen, Paint on paper, 2014

It would be impossible to ignore the works on paper as a major force that directly relates to the ceramic work. These compositions that are constructed with a gestural stroke are both studies and stand-alone work that underpins a philosophical and conceptual driven force behind her sense of creation. The process in the drawing and ceramic work reveals her hand is symbiotic, where one influences the other. Rosen seems to muster strength in her drawings as inspiration and influence for the ceramic sculpture work that follows. All the drawings, which could easily be considered paintings, are created without the consideration of color and this seems to this viewer to place the emphasis on the compositional creation of line, movement, shape and space. All the work, ceramic and on paper, is a bi-product of her internal meditations and illustrates a unique utilization and application of materials, techniques and concepts.

Annabeth Rosen, Installation view, Fired and glazed ceramic, and steel baling wire.

Annabeth Rosen studied at Alfred University (BFA) and the Cranbrook Academy of Art (MFA), and has gone on to teach at the Rhode Island School of Design, the University of the Arts in Philadelphia and the Art Institute of Chicago. Since 1997 she holds the Robert Arneson Endowed Chair at the University of California, Davis.

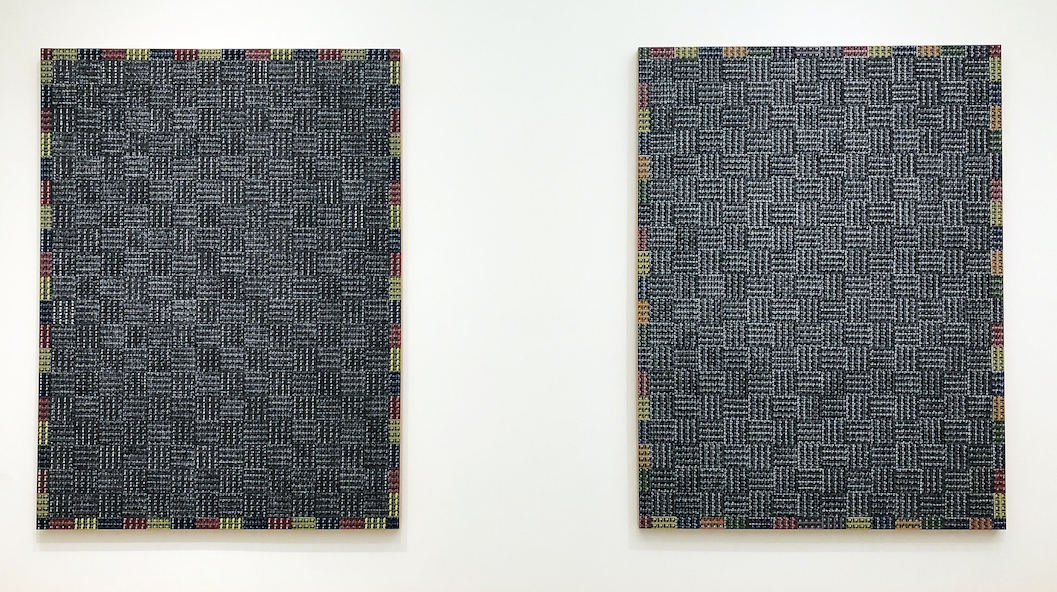

McArthur Binion, Binion/Saarinen: I, 2 – 2018, oil paint stick and paper on board, Courtesy Modern Ancient Brown

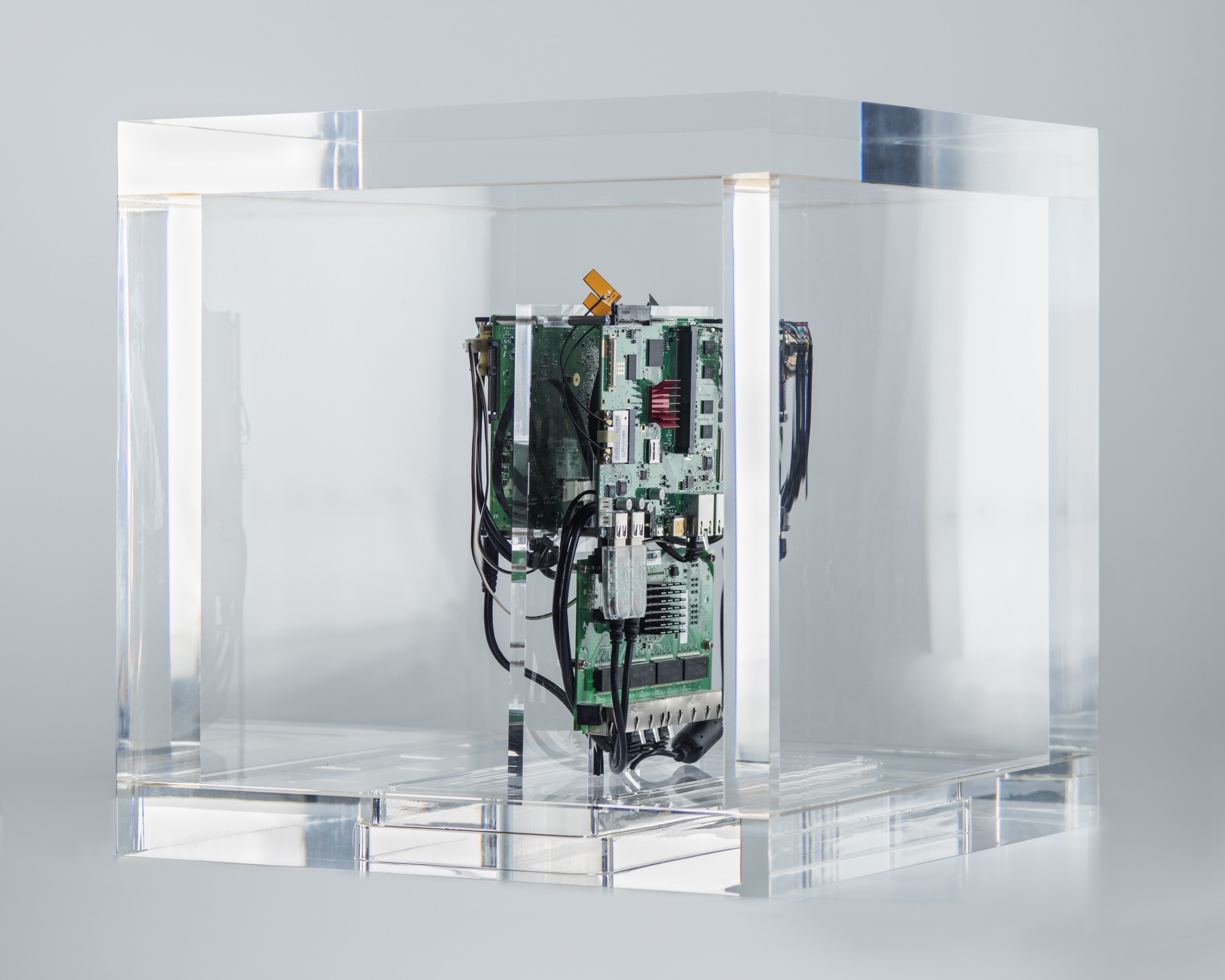

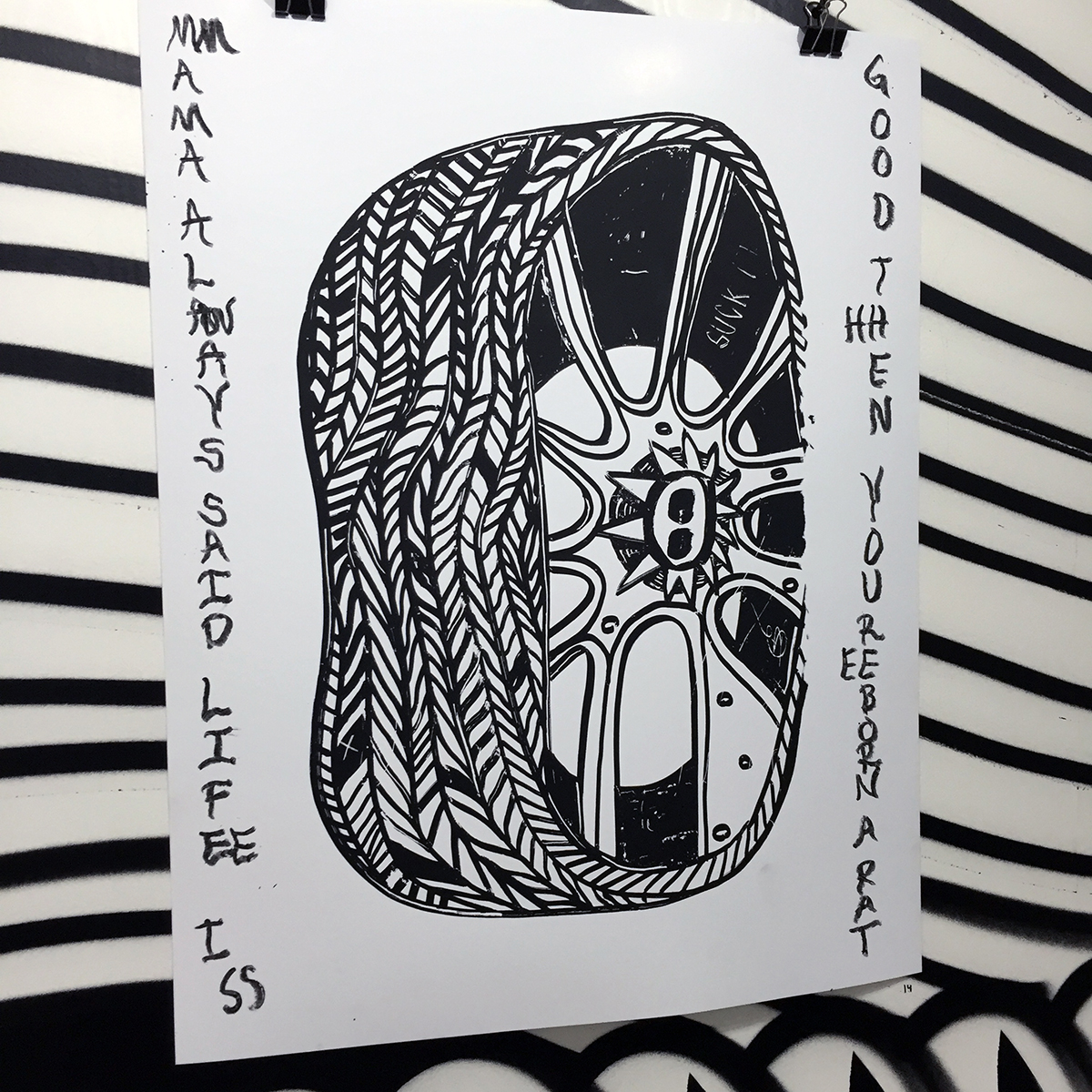

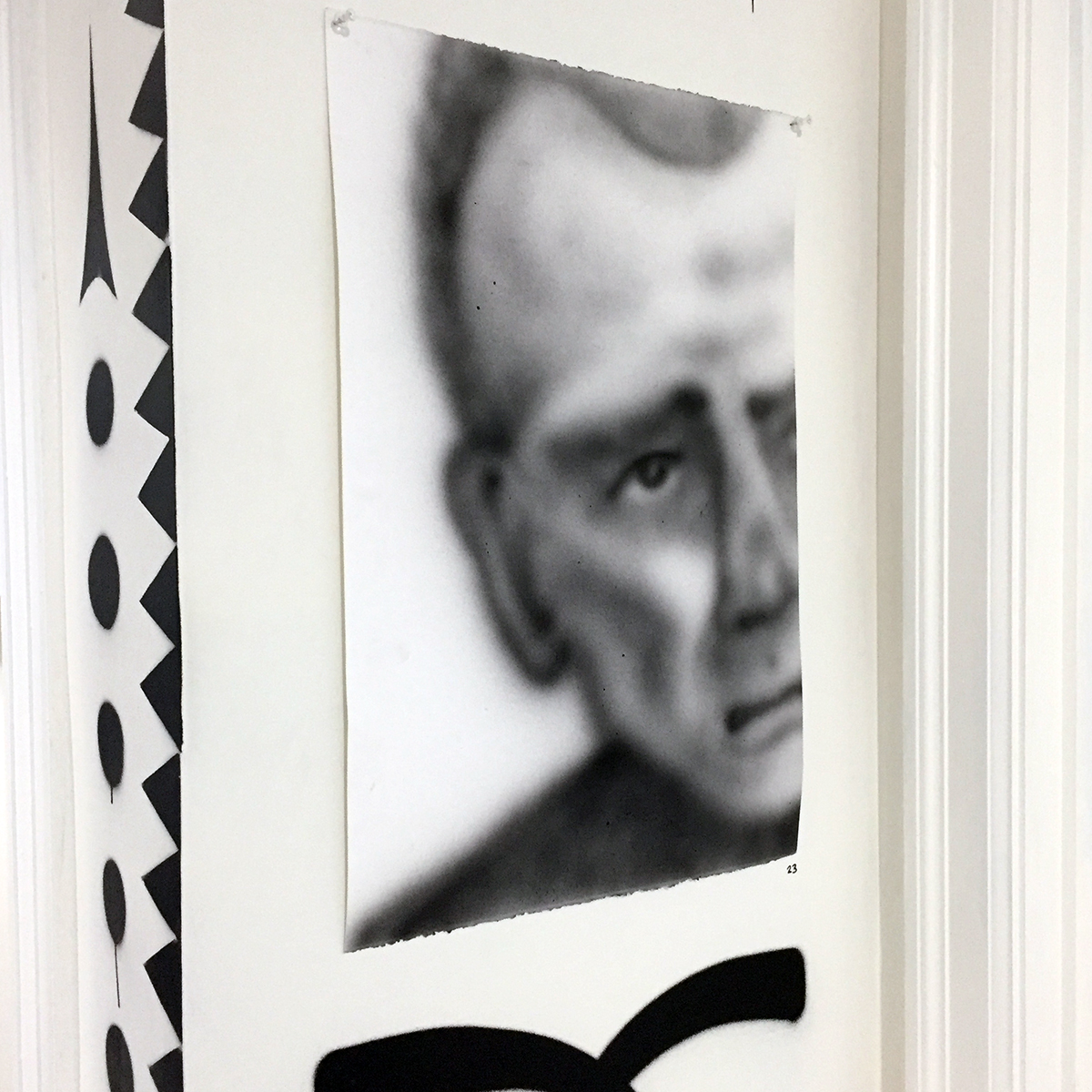

In Cranbrook Art Museum’s North Gallery, the Chicago-based artist McArthur Binion says that he had a note pinned to his wall for decades that read “Binion/Saarinen”,obviously something that came from his graduate studies at Cranbrook Academy of Art during the early 1970s. This idea is obviously generated from literally living on the campus and being surrounded by the Finnish architecture of Eliel Saarinen who immigrated to America in 1923 after the completion of the Chicago Tribune building in 1922 and who went on to be a visiting professor at the University of Michigan before developing the entire Cranbrook campus for George Booth. Perhaps it was the grids inherent in these architectural structures that made a deep impression on Binion, a Mississippi-born African American who developed his own visual language-based graphic elements, particularly circles and grids.

He says, “My work begins at the crossroads—at the intersection of bebop improvisation and Abstract Expressionism”, and at times he has described his work as rural Modernist.Binion uses oil stick, crayon and, more recently, laser-printed images to create his lushly textured and colored geometrically patterned works. The work in the Cranbrook exhibition is produced on board with small photo printed images as a background field for this tightly knit grid produced with hard pressed oil paint stick. These carefully measured grids and hand-done hatchings cover tiny images that usually have some personal meaning to the artist. In the past, the work often incorporated biographical documents, such as copies of his birth certificate or pages from his address book.

McArthur Binion, Binion/Saarinen: 2018, oil paint stick and paper on board, Courtesy Modern Ancient Brown

These new paintings use autobiographical photo imagery of both Saarinen and himself in their early thirties as a background for his delicate squared-off grid that could be easily described as minimalist abstraction from a distance. Upon close examination, this personal element attempts to bond the two together, at least from Binion’s perspective. In addition, the gallery space includes painting, drawings and furniture by Eliel Saarinen.

McArthur Binion’s paintings are largely symbolic and achieve an expressive resonance that defies the reductive materialism of minimalism. They are formed out of an unlikely confluence of influences, including such Modernist masters as Piet Mondrian, and Wifredo Lam, as well as his own southern African-American heritage, reflected in his mother’s quilts and West African textiles. Persistence and discipline fortifies Binion’s practice and his succinct, richly personal compositions.

His work is included in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

Binion/Saarinen: A McArthur Binion Project is organized by Cranbrook Art Museum and curated by Laura Mott, Senior Curator of Contemporary Art and Design.

Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped and McArthur Binion: Binion/Saarinen, at the Cranbrook Art Museum runs through March 10, 2019.