Gina Reichert & Mitch Cope, Illuminated Totem – TV Tray 2017, Wood stool, kitchen spice drawer with spices, glass fridge shelf, acrylic display box, milk cartons, crystal bowl, cathode ray tube. 40 x 18 x 16 inches All images courtesy of the David Klein Gallery

We see these documentaries on PBS about people who collect ordinary items over a long period of time, and sometimes a lifetime. They hoard collections in bedrooms, living rooms, bathrooms and the garage. The documentary will usually focus on the psychological anxiety disorder Compulsive Hoarding, a subset of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) where people equate certain mundane objects and material to their own personal identity. In extreme cases, entire houses belonging to such people become fire and health hazards.

Such is the subject of the new exhibition at the David Klein Gallery: Organizational Strategies for the After Life, by architect Gina Reichert and painter Mitch Cope. The exhibition is a combination of sculptures made from found objects, paintings from found fabric patterns, plaster castings and jars of assorted small objects, all of which were meticulously obtained from a deserted neighbor’s house in Detroit.

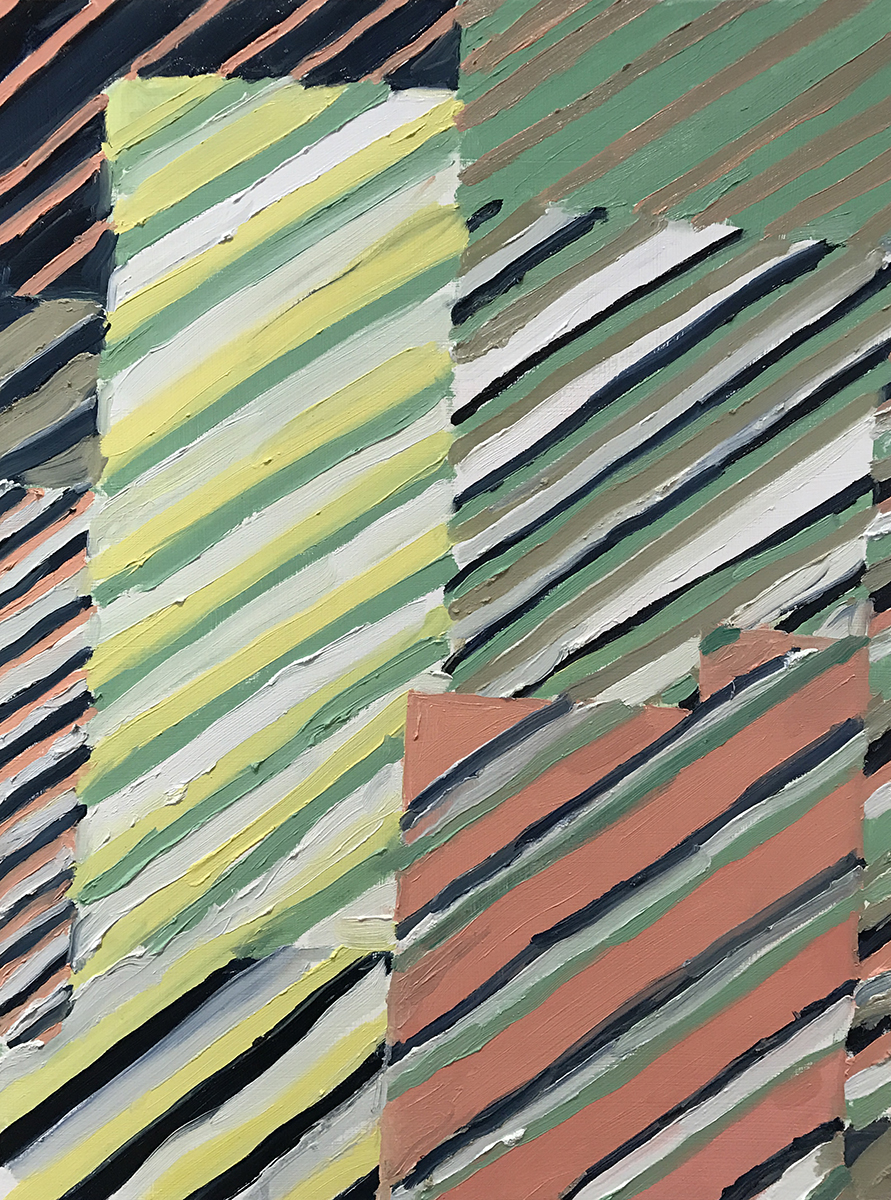

Gina Reichert & Mitch Cope Stella’s Infinite Clothes Rack, #1 – 15. All paintings based on the fabrics of the ( never worn) clothes.

Gina Reichert & Mitch Cope Stella’s Infinite Clothes Rack, #1 – 15. All paintings based on the fabrics of the ( never worn) clothes.

The exhibition represents the culmination of six years of working together as a husband and wife team to distill and categorized the home of a person with Compulsive Hoarding Syndrome. In a statement they say,

“At the risk of being overly nostalgic for a past time, we pressed on in our search to reveal what we now believe is less a picture of the past, and more of the afterlife. Too often we romanticized past generations, especially here in Detroit, as being better or greater, cleaner or safer, than it is now, but we have become quite easily convinced through our research, that although the physical aspect of the houses were in a better shape than now, (they were brand new then) the last hundred years of life on Klinger Street were not necessarily a better time.”

Over time, both the painter and the architect, became increasingly interested in the house next door, abandoned by its owner, forcing them into a process of finding and categorizing thousands of materials produced over multiple generations that went back a century. Part of this exhibition is a video presentation of the documentation process, using four video screens with audio support. The video helps the viewer understand the magnitude of their work and the transformation of materials into objects of art.

Is there a context for their repurposing of an enormous amount of material for an art exhibition? Certainly, there is a history of found art objects. The amassment and display of found objects for their aesthetic qualities dates back to at least the 16th century, when the collections of individual enthusiasts were displayed in private “cabinets of curiosities,” or what the Germans called “Wunderkammer.” But it wasn’t until the 1900s that artists began to incorporate found objects into sculptural works as an artistic gesture in 1917, where Marcel Duchamp created his “readymade” The Fountain, consisting of a porcelain urinal signed R. Mutt.

Gina Reichert & Mitch Cope, Gathering of the Scattered – Vision 2017, Electronic tubes, bell jar, tape. 11 x 5 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

But where this current exhibition breaks from found art objects repurposed as art is this idea presented by Cope and Reichert where they write,

“ What if the things we use and collect in our lives carry more than the representation of what they mean to the individual who owns them, but also carry a small part of their spirit?” They go on to say, “Or if the spirit of things attaches part of it to its user?” They raise many interesting questions about the spiritual relationship between the owner and the object, all of which is explained in their writing that is available as part of the exhibition.

Gina Reichert & Mitch Cope, lluminated Totem – Root Cellar 2017, Marble book ends, preserves in glass jars, acrylic display box, glass furniture feet, enameled steel tub, assorted glass servingware. 32 x 15 x 15 inches

Putting this aside, many of the paintings and sculptures are quite beautiful and stand on their own, without the complex environmental project that surrounds and embodies their creations.

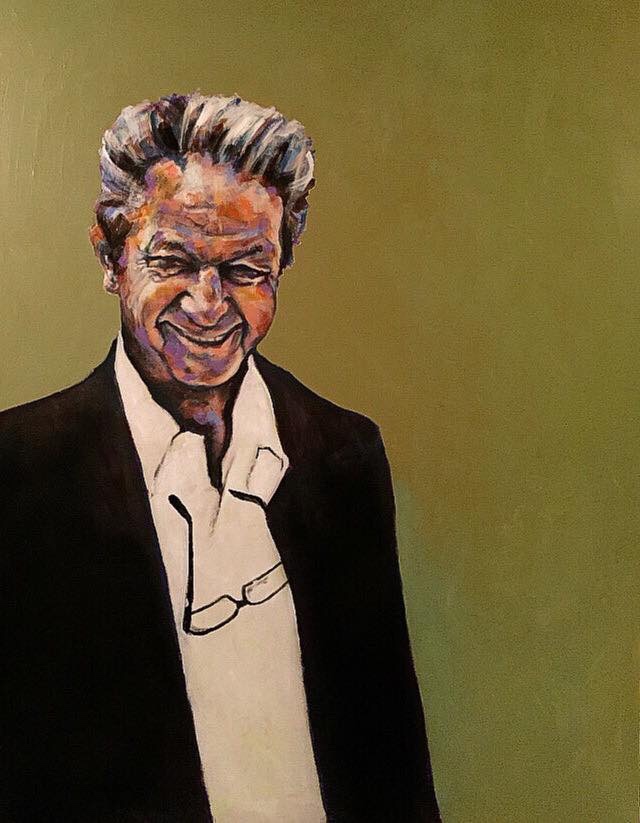

Gina Reichert holds a Master of Architecture degree from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a Bachelor of Architecture from Tulane University. Mitch Cope, a native Detroiter, has lectured widely throughout the US and Europe. Cope holds a BFA from College for Creative Studies, Detroit and an MFA from Washington State University.

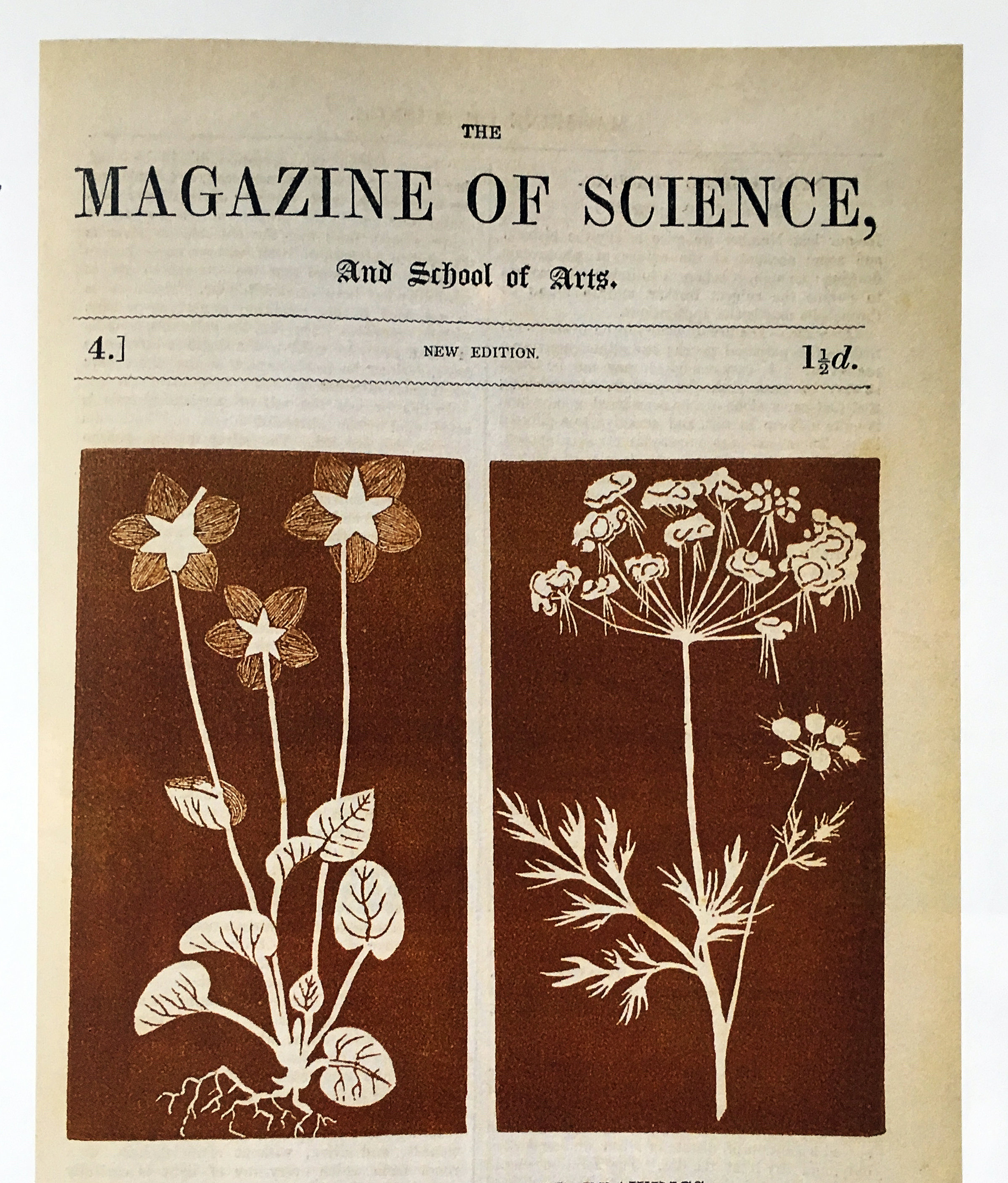

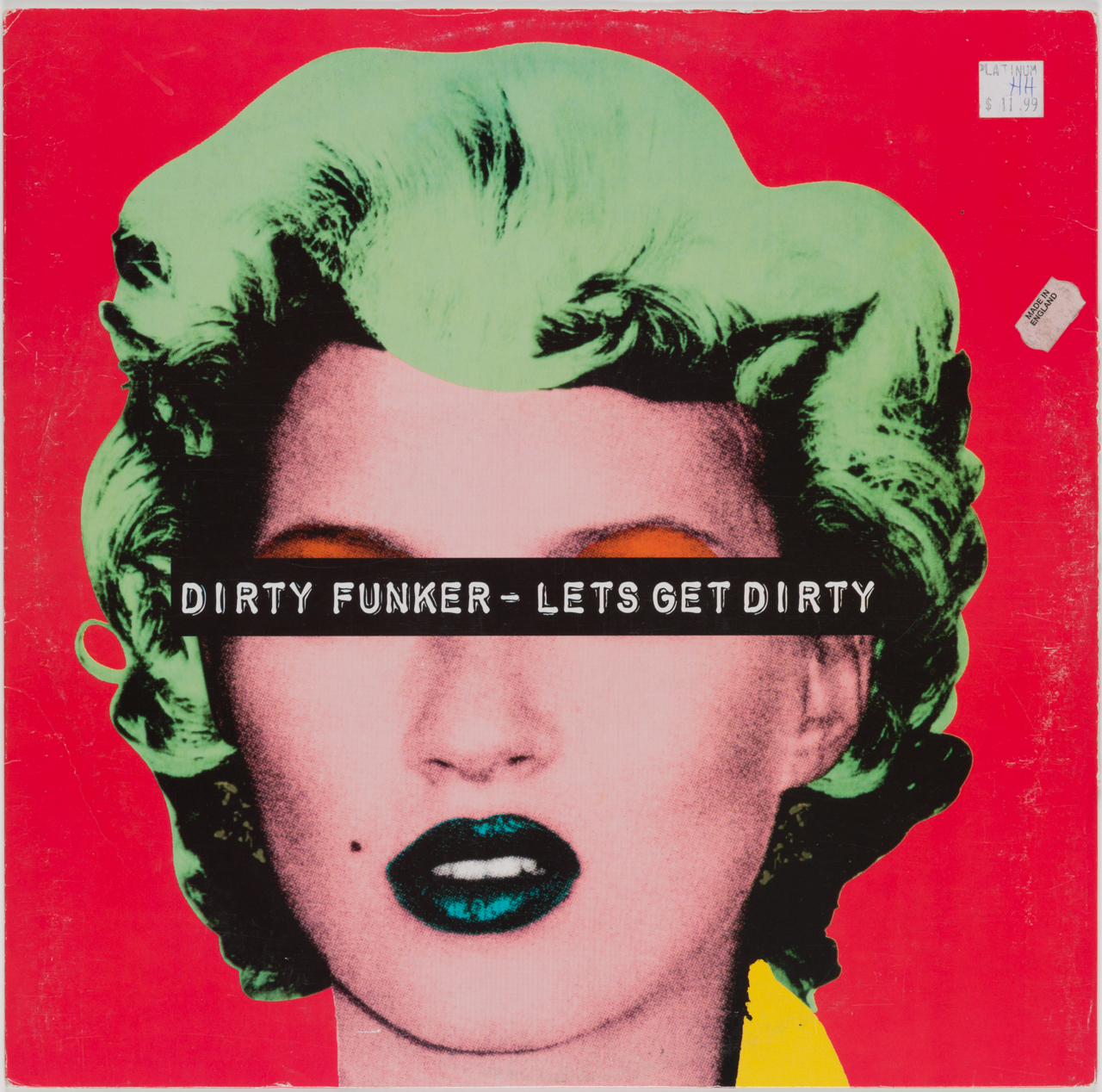

Banksy on Vinyl: The Record Covers

Banksy, Dirty Funker, Let’s Get Dirty, 12” Single 2006, Record album. 12 x 12 inches

The British artist Banksy – graffiti master, painter, activist, filmmaker and all-purpose provocateur – is also a prolific designer of album covers. Since 1998 Banksy has designed the cover art for almost 40 albums. Many of the albums were produced by small independent record labels for obscure British bands and were usually not commercially successful. As a result, Banksy album covers were not widely distributed and only a small number have survived. A collection of fifteen record covers and the actual albums, all framed and behind glass, comprise the exhibition Banksy on Vinyl in the second room at the David Klein Gallery.

Banksy, Various Artists, We Love You So Love Us, 12” album 2000, Record album. 12 x 12 inches