DIA Presents a Multimedia Exhibition of Ninety works of American Art 1830-1960

How long have people been dancing? Probably longer than they were playing with fire. Nureyev captured the hearts of millions of ordinary people, while Baryshnikov stunned the critics and Martha Graham created the full-codified modern dance with her deviation from classical ballet.

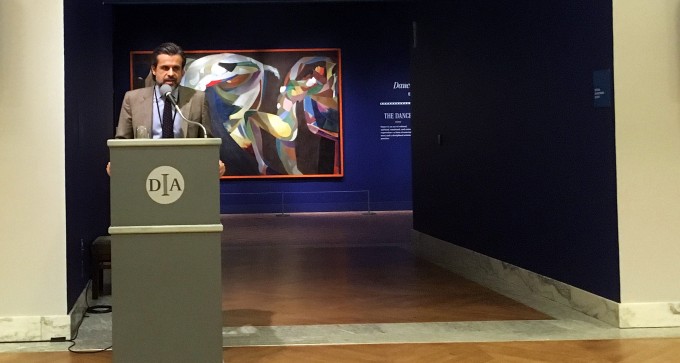

Director Salvador Salut-Pons at Podium introducing the Dance! 1830 – 1960 exhibition

Coming off a very successful 30 Americans exhibition, Salvador Salort-Pons took the podium to introduce the new exhibition Dance! American Art 1830-1960, at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Opening March 29, 2016 the multimedia exhibition surveys the history of Dance in America as seen through the eyes of American Artists.

“This is the first major exhibition to explore visual art related to American dance. Dance has such a rich history and has touched all segments of American society,” said Salvador Salort-Pons, DIA director. “This exhibition is not only about the representation of the art of dance, it explores how artists were inspired by how Americans move, how they interacted with each other and experienced the rhythm of music.”

It was clear from her remarks at the media preview that curator Jane Dini had been working on this exhibition since her time spent working at the DIA, and that this exhibition had been in development over the past five years. In Dance!, Ms. Dini has been able to create her life’s dream.

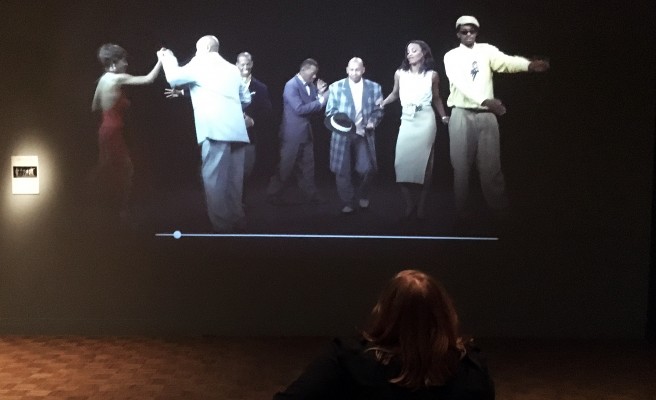

“In addition to the outstanding works of art, it was important for me to have the voice and expertise of dancers within the exhibition itself,” said Jane Dini, now associate curator of American Painting and Sculpture, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and curator of the exhibition. “They help illustrate how dance as an artistic form had an enormous impact on the fine arts, especially painting and sculpture.”

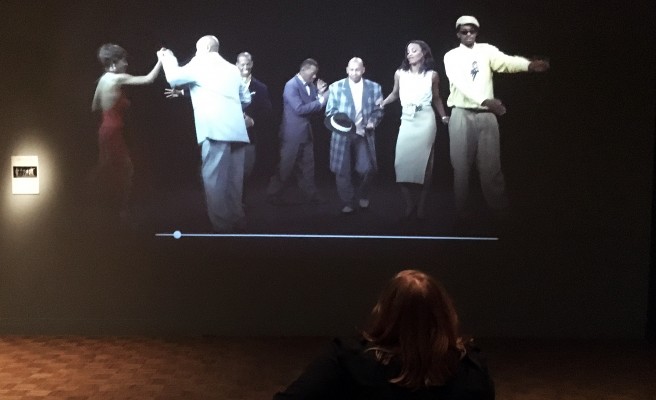

Video of Dancers – One of several through out the exhibition

I never danced, but my parents were both professional dancers, which gave me some built-in personal interest. My parents were both recruited by a New York dance company in the mid-1930’s. In addition, in the 1980’s, I facilitated an artist-in-residency program in the Utica Schools, where we brought the Detroit City Dance Company, under the direction of Carole Morrisseau, into our forty schools over the period of a school year. Getting to know the day-to-day lives of dancers is something that stayed with me. I learned they lived in a physical world and often from moment to moment. The dancers had a unique devotion to their bodies, especially their ankles and feet.

Ms. Morrisseau is now a visual artist practicing in Detroit, and I caught up with her at the Scarab Club, “The concept of the current exhibit at the DIA is a credible one and exceptional in its undertaking. I believe there is a very strong relationship between the visual and performing arts. Hopefully this exhibit will expand the public’s view of the art of dance and visual art.” Carole Morrissieau will exhibit her visual artwork opening this month at the Scarab Club.

Arthur Bowen Davies, 1862 – 1928, Dances, 1915

Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928), often called an Ashcan painter, was an avant-garde American artist who spanned the boundaries between the 19th-century romantic tradition and early twentieth-century modernism in the United States. He was born in Utica, New York and studied at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1878 and at the Art Students League in New York in 1887. His idyllic figurative pastorals are often said to harken back to Botticelli. Davies supported the new abstract movement and participated in the early formation of MoMA in New York City. His work was collected ahead of its time by the Phillips Collection. In Dances, 1915, Davies used faceted planes of color to define the moving figures, resulting in a pattern of color evoking a dance celebration.

Eastman Johnson, Negro Life at the South 1859, Oil on Canvas

Genre painter Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) had a turning point in 1859 with the exhibition in New York of his Negro Life in the South. His ambiguous picture of the leisure activities of a group of slaves was a sensation at a time when the topic of slavery was being universally debated. In the painting, a mother encourages her son to dance to the music of a banjo player. Born in Maine, Eastman Johnson was educated in Europe, where he was inspired by the work of Dutch Masters. He is best known for his realistic portraiture and as a co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

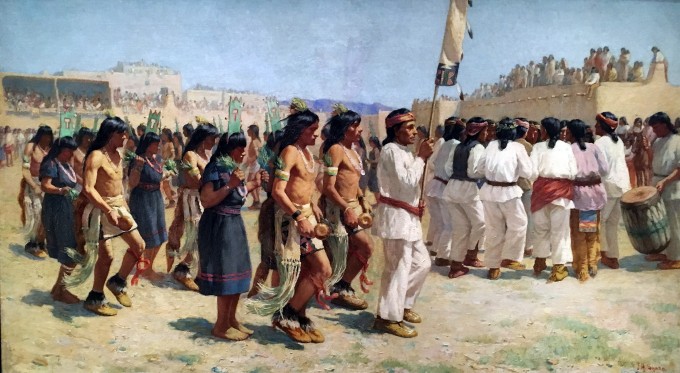

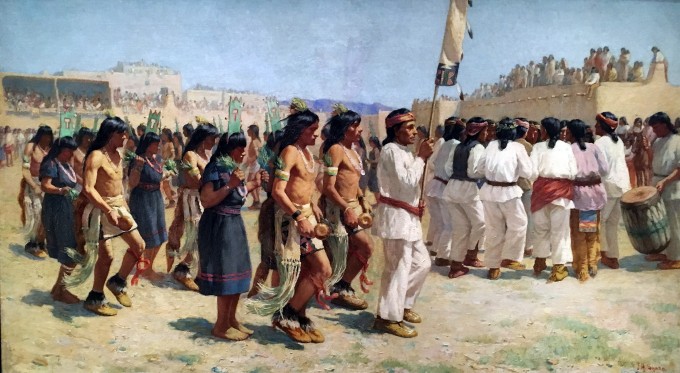

Henry Joseph Sharp, The Harvest Dance 1894, Oil on Canvas

Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953) was an American painter best known for his work painting Native Americans. Sharp was born in Bridgeport, Ohio to Irish immigrant parents and studied at the Academy of Fine Arts at Antwerp. Sharp’s first trip to the West was in 1883 at age 24. He visited pueblos in New Mexico, Santa Fe, Albuquerque and Tucson. In his work, Harvest Dance, Sharp illustrates a strong skill set for painting the figure and depicting the sunlight on his subjects. Sharp went on to become one of the six founding members of the Taos Society of Artists.

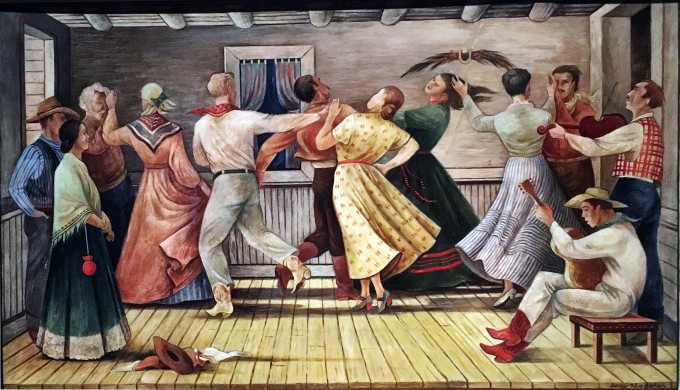

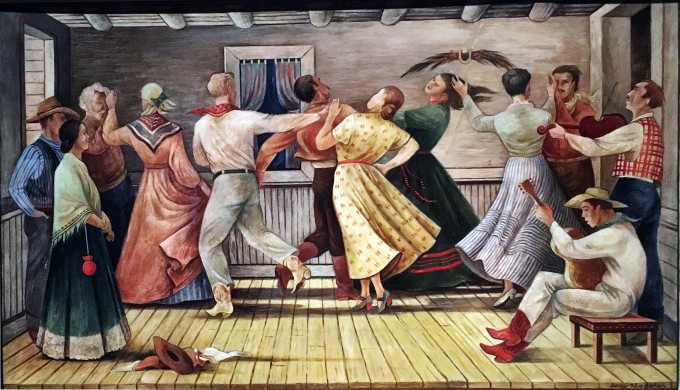

Sargent Claude Johnson, Dance Hall Study, 1935, Tempera, Watercolor, and Graphic on Illustration Board.

Born in Boston on October 7, 1887, Sargent Johnson was the third of six children of Anderson and Lizzie Jackson Johnson. Anderson Johnson was of Swedish ancestry, and his wife was Cherokee and African American. As a member of the bohemian San Francisco Bay community and influenced by the New Negro Movement, Sargent Johnson’s early work focused on racial identity. Johnson’s art ranged from African American masks to producing paintings of local folks and creating small, figurative sculptures. Dance Hall, a study in watercolor and graphite, was a study for the San Francisco Housing Authority mural.

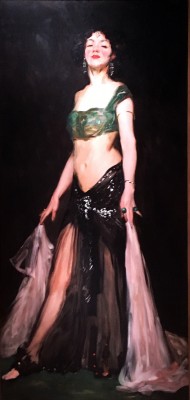

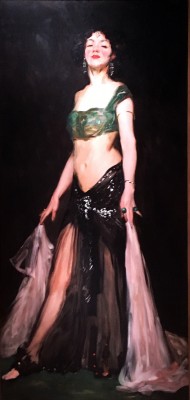

Robert Henri, Salome Dancer, 1909, Oil on Canvas

Robert Henri (1865 – 1925) was a leading figure in the Ashcan School of American realism who helped organize a group known as “The Eight.” Henri studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia and under Thomas Anshutz, a protégé of Thomas Eakins. Art critic Robert Hughes declared that, “Henri wanted art to be akin to journalism. He wanted paint to be as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter, as real a human product as sweat, carrying the unsuppressed smell of human life.” When Henri painted the dancer in the role of Salome, a seductress from the New Testament, in 1909, it was rejected by the National Academy because the exposed leg was considered too controversial by the fine arts world. Robert Henri was a popular and influential teacher at the Art Students League of New York.

Paul Manship, Dancer & Gasell, Bronze, 1916

Paul Manship (1885 – 1966) was born in St. Paul, Minnesota and began his art studies at the St. Paul School of Art in Minnesota. From there he moved to Philadelphia and continued his education at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. At one time the country’s most famous exponent of Art Deco, he embraced archaic vocabularies of Greek, Roman and Indian art to create decorative, stylized, Neoclassical works. The statue in the fountain in New York City’s Rockefeller Plaza, Prometheus (1933), is one of his most famous works. The bronze Dancer and Gazelles, was completed in 1916 and won the National Academy prize in 1917. The tension in the small areas between the figures emphasizes the dancers’ gestures, which command the gazelles’ movements.

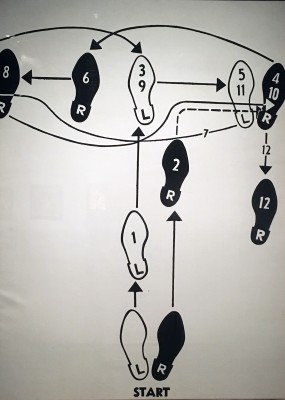

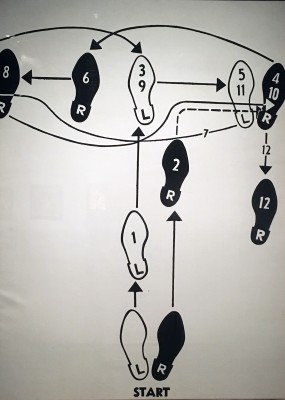

Andy Wharhol, Dance Diagram, 1962, Casein and Graphite on Linen

Andy Warhol (1927 -1987) a leading American Artist who ushered in the Pop Art movement, began to make paintings of iconic American objects such as dollar bills, mushroom clouds, electric chairs, and the most famous Campbell’s Soup can. The New York opening at the Stable Gallery on November 6, 1962, was Warhol’s first one-man show and also where he first debuted Dance Diagram. It was presented in a series featuring six additional Dance Diagrams with the source material taken from the Dance Guild’s 1956 book Fox Trot Made Easy. It shows Warhol’s interest in selecting objects from American culture as subjects for his artwork.

Biba Bell, a Detroiter who recently completed her PhD in performance studies at N.Y.U., says, “The ways that dance is taken up symbolically within visual art is so interesting! I’m imagining that each piece produces these figures and forms in diverse and unique ways, but there is something about the dancer, the body that is dancing, filled with movement and the moment and a kind of excess of life/ liveliness that is astounding and so important when depicting any culture.”

If you’re not a dance aficionado, Dance! American Art 1830 -1960 at the DIA might spark your interest, and while you’re in New York City, get tickets to see An American in Paris, by the Tony Award-winning choreographer Christopher Wheeldon who has created a critical and commercial success breaking new ground by bringing ballet to Broadway set to the music of the Gershwins.

I recall, my father watching black & white films of Fred Astaire & Ginger Rogers for hours, and he tap-danced into his eighties. When I was very young, attending a family wedding, my parents did something rare; They danced. Everyone gathered around to watch them exhibit their talents publicly for maybe the last time. I was so very proud.

The Detroit Institute of Arts deserves credit for this curatorial creation of its own that will travel to the Denver Art Museum, July 10 – October 2, and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, October 22, 2016 – January 16, 2017.

Exhibition tickets are $14 for adults, $10 for Wayne, Oakland and Macomb county residents, $7 for ages 6–17, $5 for Wayne, Oakland and Macomb county residents ages 6–17, and free for DIA members. Admission is free every Friday. School groups need to register in advance. Tickets at dia.org or 313-833-4005