Oakland University Art Gallery opens the fall season with a faculty exhibition

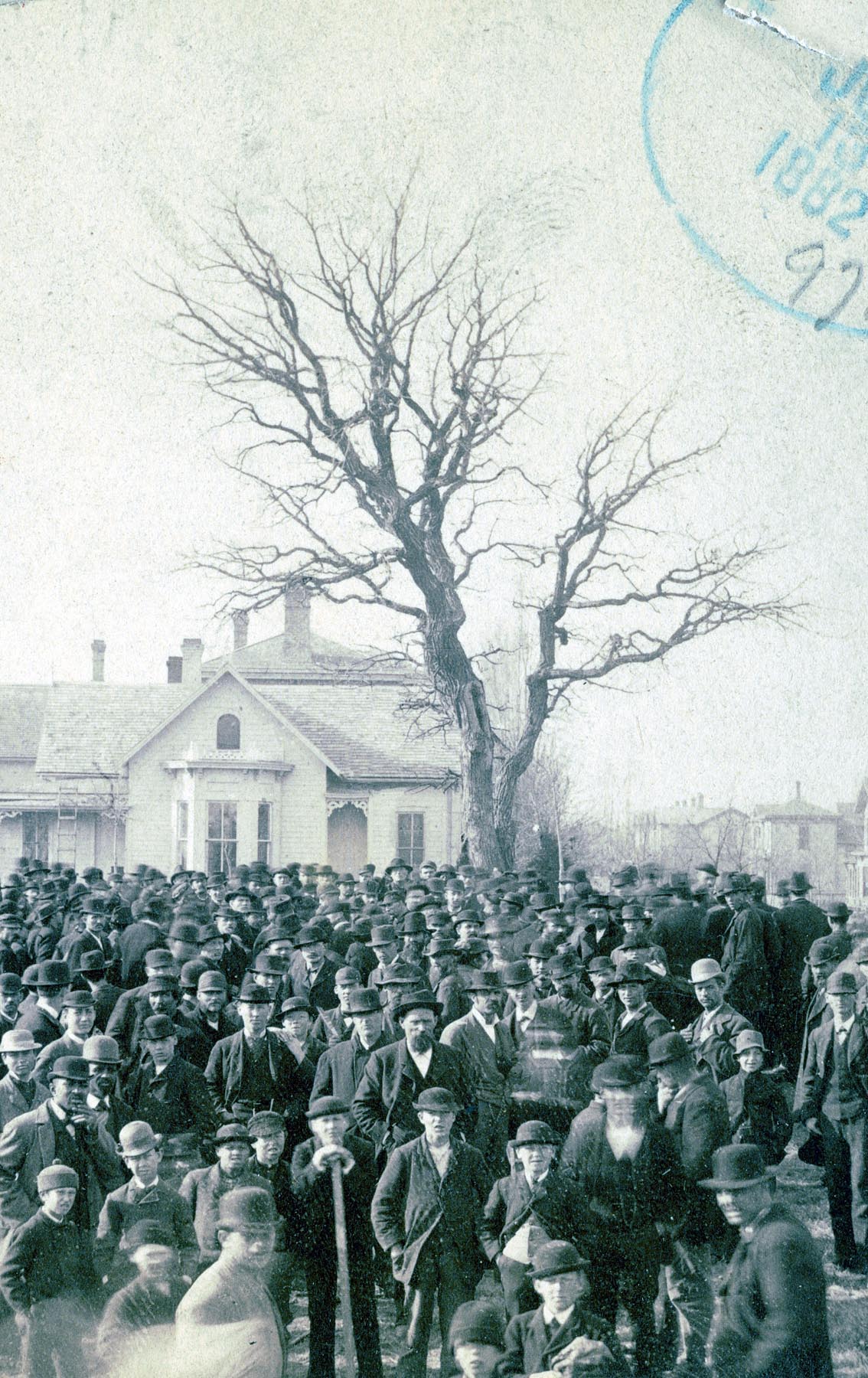

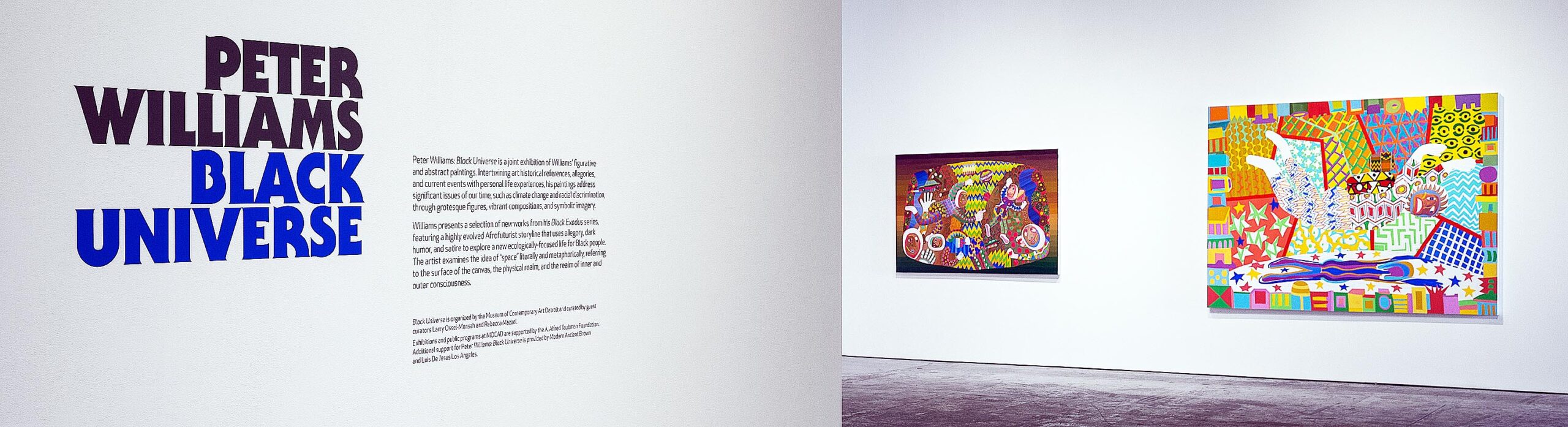

Installation image, Moving Forward, OUAG, 10.2020

Every fall since I can remember, the Oakland University Art Gallery, under the direction of Dick Goody, Professor of Art, Chair of the Department of Art & Art History and director of the Oakland University Art Gallery, has started off the fall season with a large curated show (supported with a four-color catalog) that would have required months in the planning and often brought in artwork from various parts of the United States and beyond. Given the current situation under Covid 19 restrictions, Goody has opted to curate a faculty show, including his own work, supported with information on the web site to provide a venue for his faculty members. I suspect he is waiting until later in 2021 to present the public with something more in keeping with his previous tradition. Nevertheless, the gallery is open to the public, with Covid 19 restrictions in place, noon – 5 pm, Tuesday through Sunday, closing November 22, 2020. It’s worth a visit.

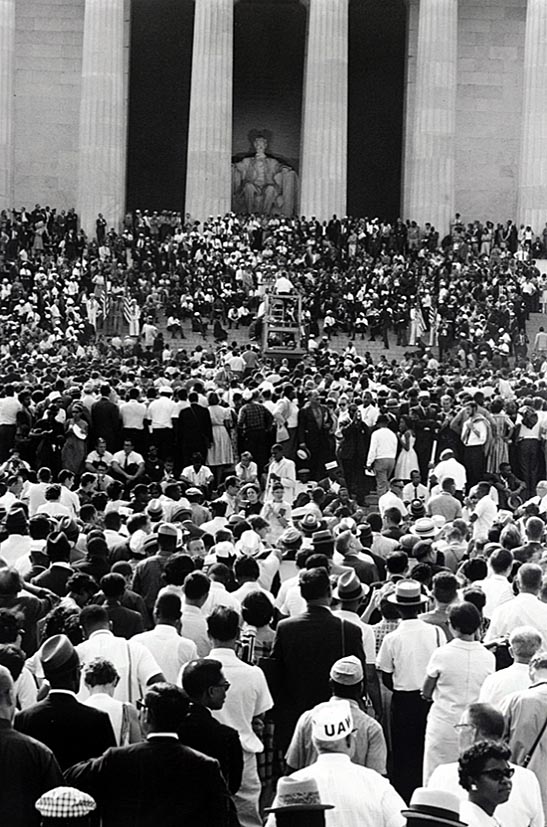

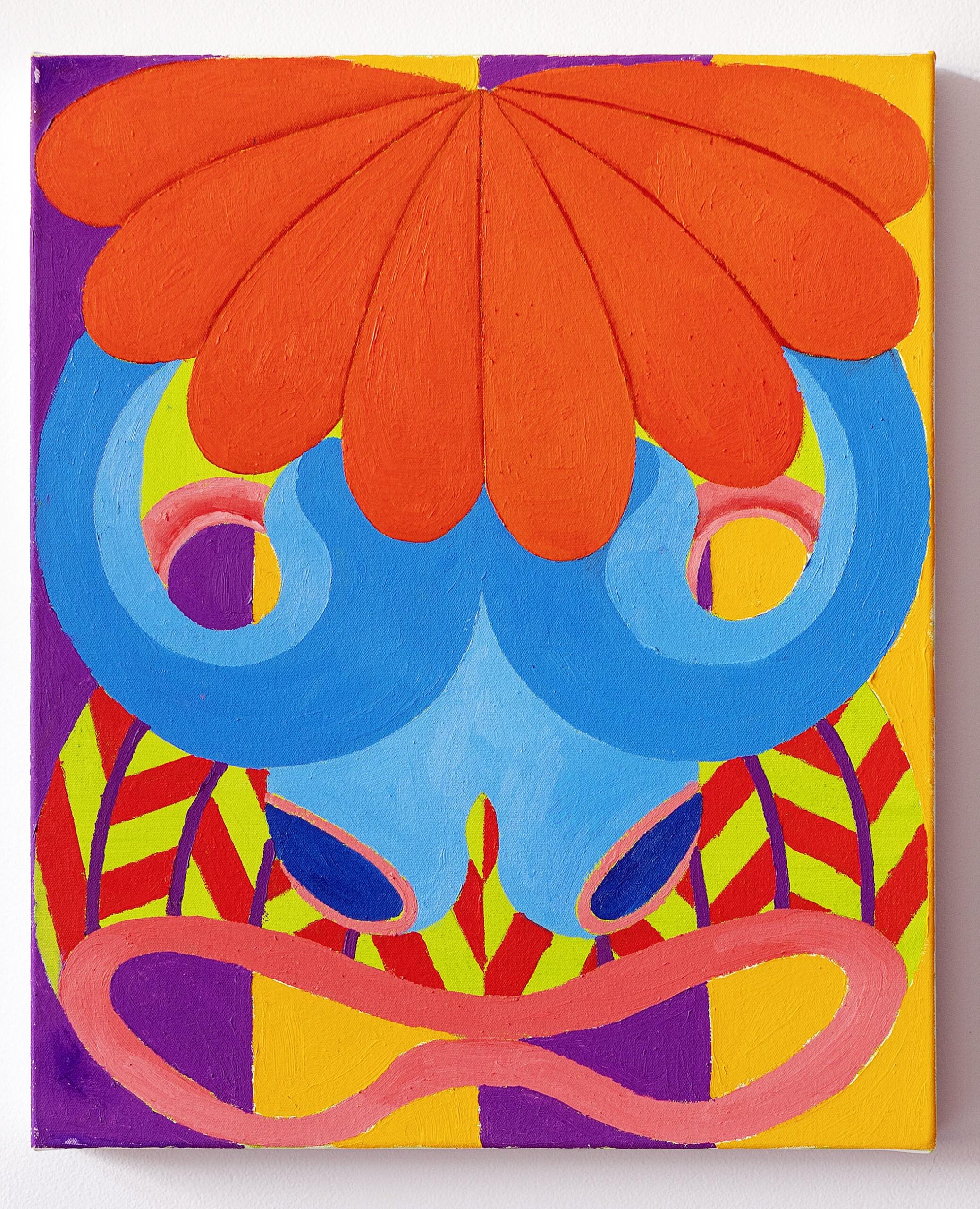

Cody VanderKay, Flattening, 32 X 43 X 3 20, PAINTED OAK, 2020

The work of art that jumped out at me was Backstage, by the artist Cody Vanderkaay, an eclipsed shape object with a highly constructed surface of vertical squared planes painted in progressive shades of green. It’s a new experience. Not a figure, landscape, still life or photo image reference, but a newly experienced object. In the surge of artist returning to painting the figure, Vanderkaay stays on course with his abstract imagery presenting a consistent path for his work to expand and enlighten.

He says in his statement, “The artworks explore and consider how individuals, objects and spaces interrelate, and how relationships between these entities develops over time. The sculptures displayed in this exhibit signify various states of change: A circular plane of wood appears pleated and compressed to produce a variegated effect; a vertical square column bends in diverging directions under invisible force; a small-scale architectural relief implies stories behind the scenes.” Cody VanderKaay was born and raised in North Metro Detroit and graduated from Northern Michigan University with a B.F.A. in Sculpture and from the Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia with an M.F.A. in Sculpture.

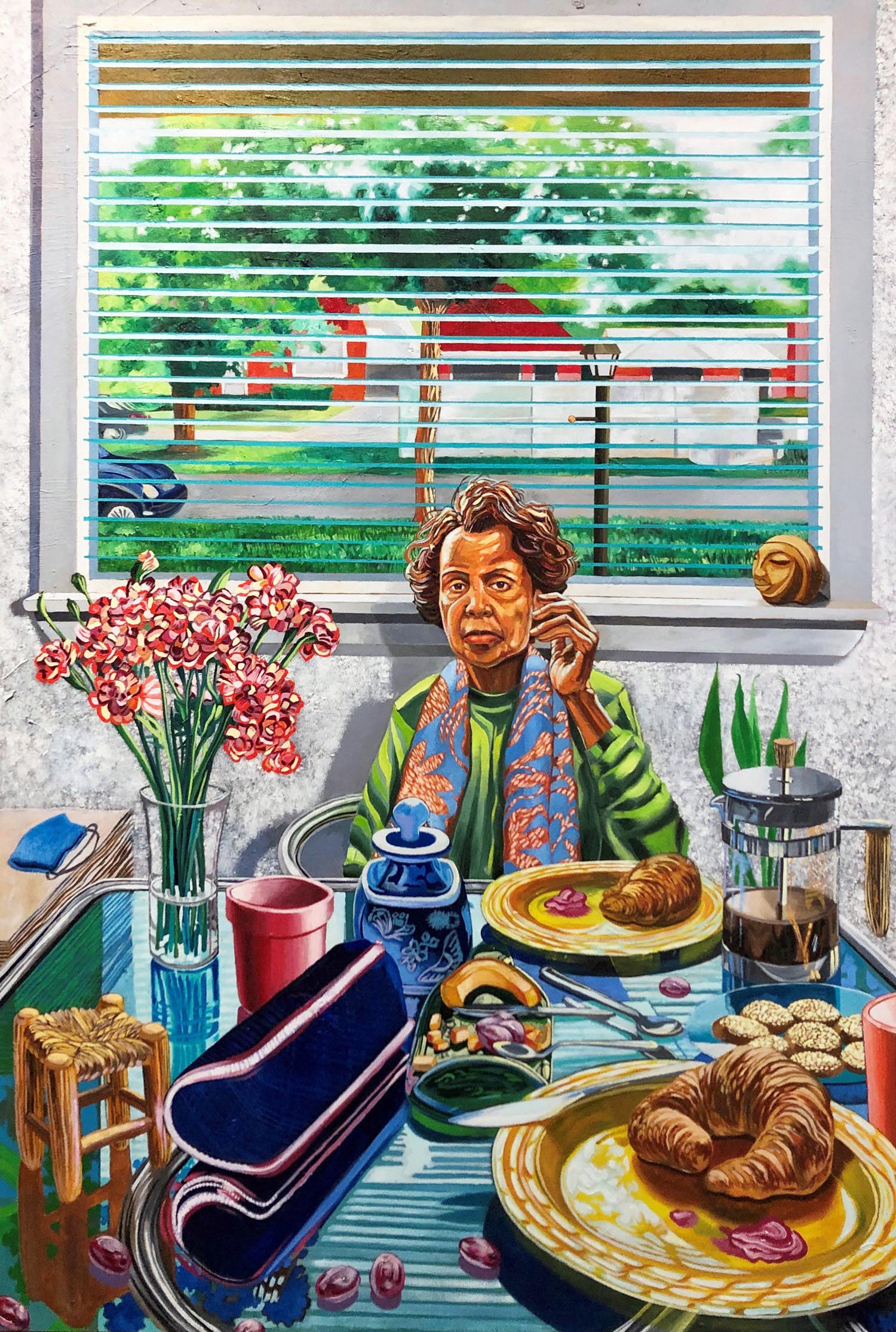

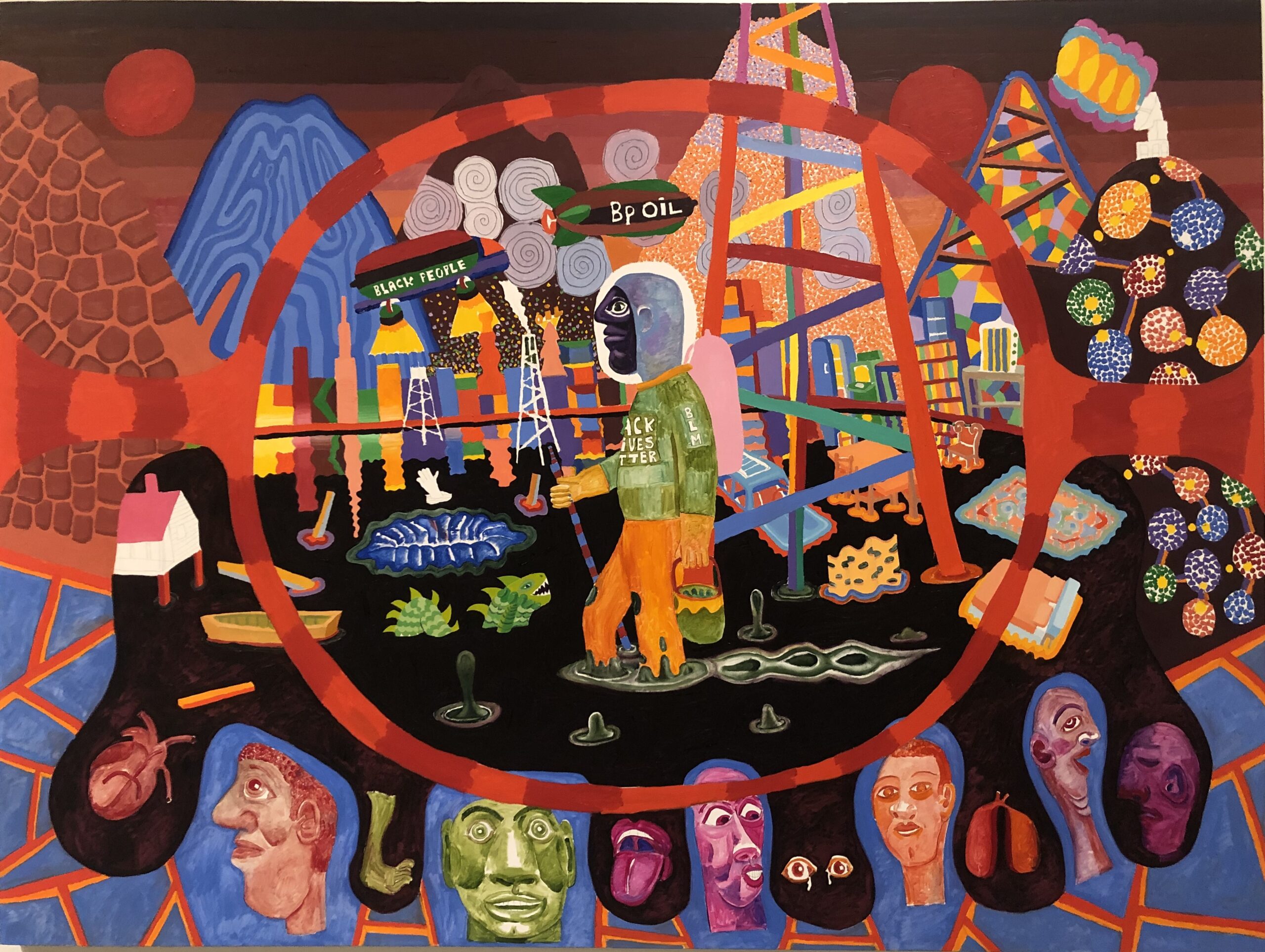

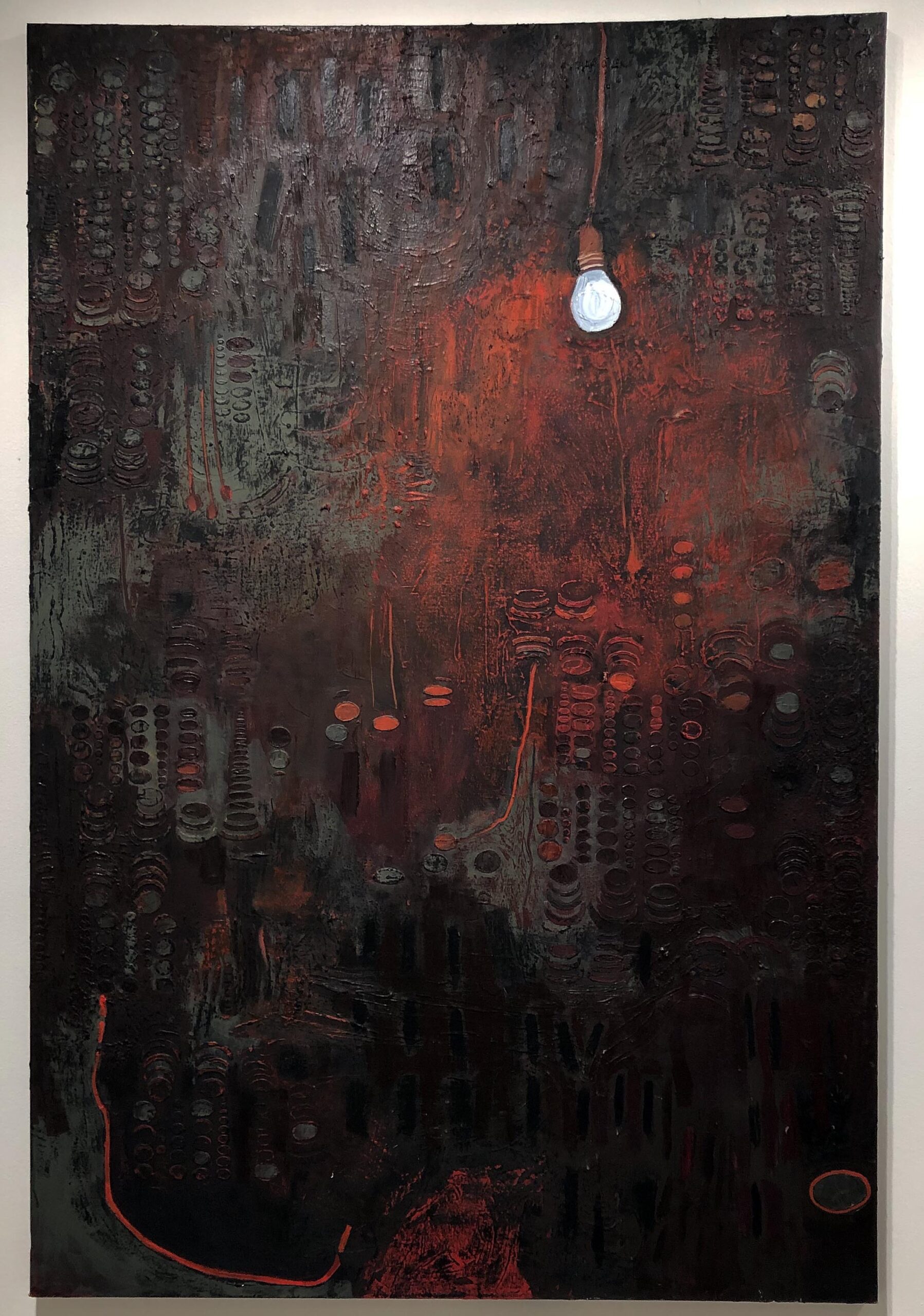

Sally Schluter Tardella, Bulb, Oil on Canvas, 72 x 48”, 2020

The work of Sally Schluter Tardella, Bulb, also attracted this writer, a sort of melancholy oil painting that revolves around a painter’s favorite subject, light. This single bulb illuminates its surrounding vertical space filled with tones of red, brown and grey and a repeating motif of ellipses, lines and small shapes creating a somewhat mysterious abstract space. It is the idea that draws the viewer to the work of art highlighted by something we all recognize: a small domestic light bulb.

Tardella says in her statement, “A wall surrounds, encloses, immures. A barrier, it is a continuous surface that divides rooms, separates and retains elements. I see transparent and opaque layers of material from above and below, as I imagine cross sections of wood beam structures folding into new systems of wall. In Bulb the atmosphere is lit by the single light bulb, the space defined is both deep and blocked by surface texture, whereas in Light, the light source is transparent and the space is shallow. In Fan the screen is made of tactile architectural symbols.” Sally Schluter Tardella uses architectural tropes as metaphor to explore personal ideas of body, gender, culture, and politics. Tardella moved from New Jersey to study Painting at Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Susan Evans, Some Art From My House, Mixed Media, 2020

This eclectic collection of photo imagery, Some Art From My House, is exactly that, a mixture of small photographic images that vary in color size, format and subject, which is meant to demystify the taking of images and their content. There are images I like and others not so much, but it is a window into her perception of what photography is, at least for her.

Evans says in her statement, “ What we look at everyday becomes familiar and generally, familiar things become preferences which define ideas, beliefs and experiences. Although I have not made any of these works as a group these pieces become an intimate self-portrait. The true meaning of the piece is not about each image individually, instead it is about the sum, juxtaposition and connection between the different elements. Who then is the true author of the artwork?” Susan E. Evans received her B.F.A. in photography/holography from Goddard College, and an M.F.A. in photography from Cornell University.

The Moving Forward exhibition features the work of the full-time faculty of the Department of Art & Art History at Oakland University that includes the work of Aisha Bakde, Claude Baillargeon, Bruce Charlesworth, Susan E. Evans, Setareh Ghoreishi, Dick Goody, David Lambert, Lindsey Larsen, Colleen Ludwig, Kimmie Parker, Sally Schluter Tardella, Maria Smith Bohannon and Cody VanderKaay.

OUAG Hosts Faculty Exhibition Moving Forward closing November 22, 2020