History Told Slant: Seventy-seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

The exhibition History Told Slant is occasioned by the tenth anniversary of the opening of the Broad Art Museum, a space designed by architectural megastar Zaha Hadid, and which in 2012 became the new home to the robust collection of art formerly displayed at Michigan State University’s Kresge Art Museum. The collection itself marks its 77th year, and on view is a sprawling cross-section of highlights. While serving as an upbeat celebration of the museum’s collection, this exhibition also engages in dialogue about the ethics and practice of collecting and displaying art, particularly regarding representing voices traditionally underrepresented in museum spaces.

The exhibition opens with a strong salvo of gestural character studies, representing a wide variety of time periods and cultures. A small self-portrait by Rembrandt, a bronze study by Rodin, and a portrait bust by Reuben Kadish, though vastly different in style, pair well in their scribbled rendering of the human figure. These, along with an ensemble of 19th century Benin bronze figures hint at the varied ways different artists from different cultures abstract the human form, and gently flaunt the cultural and geographic reach of the Broad’s holdings.

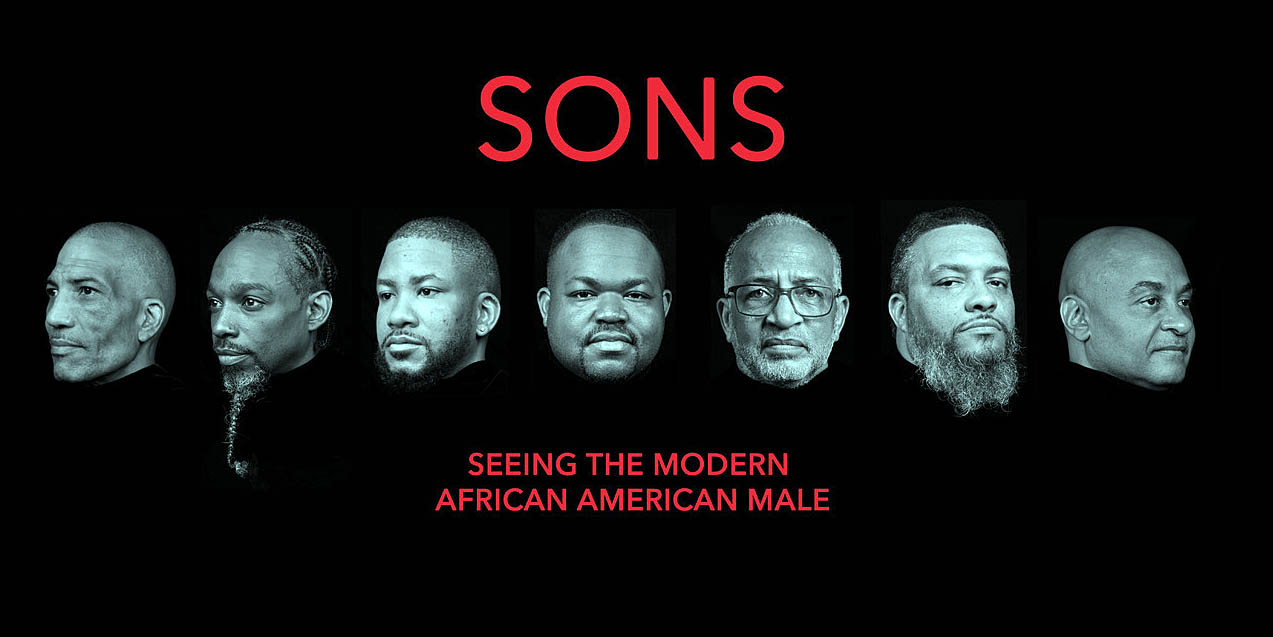

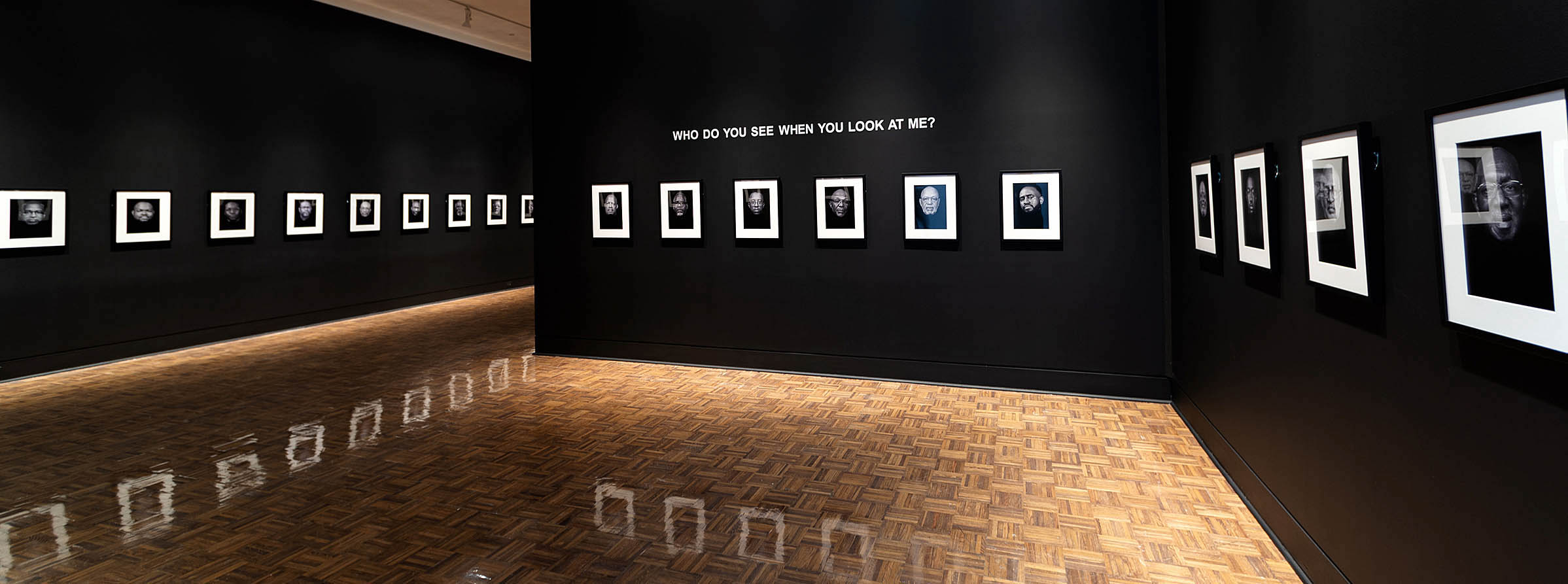

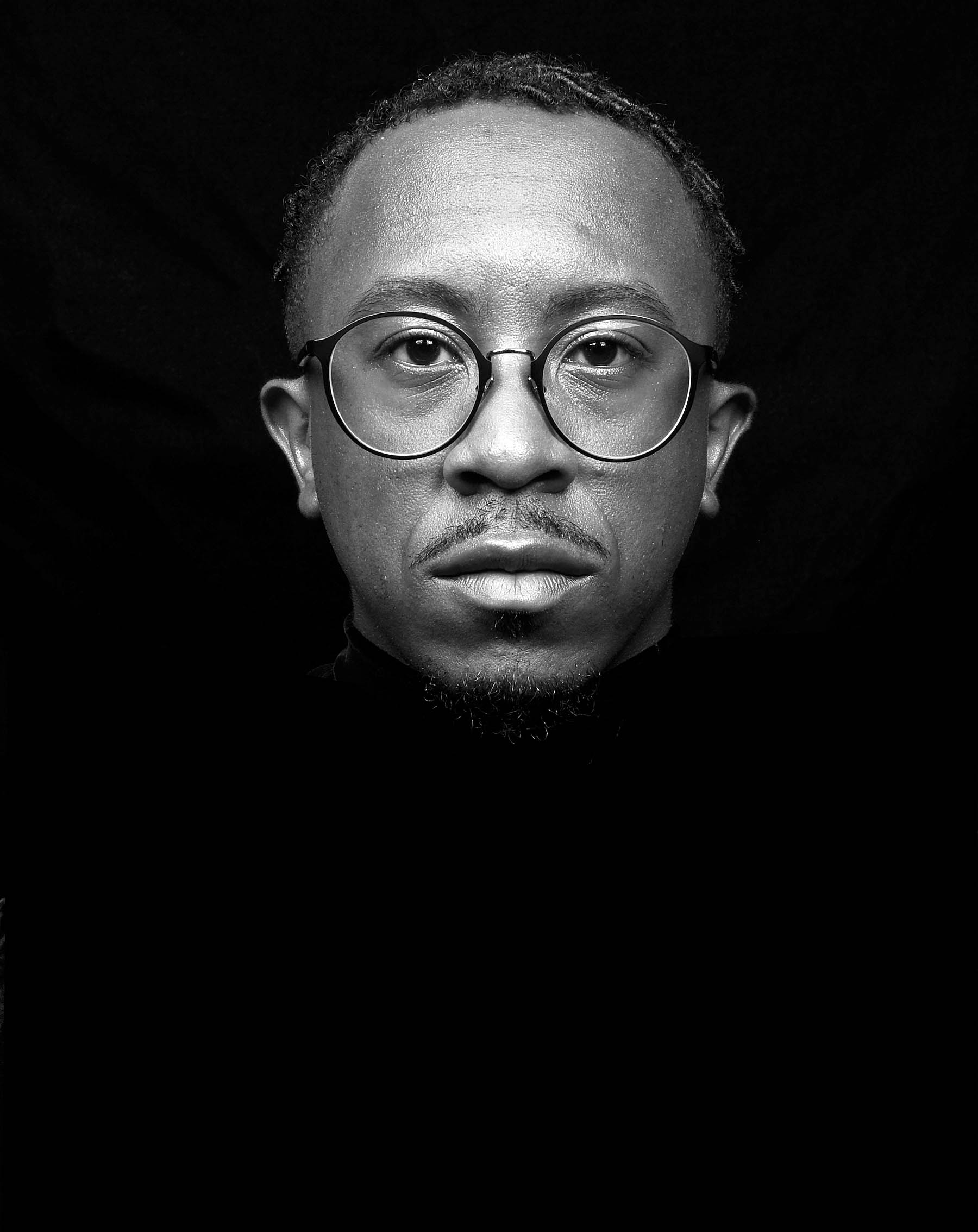

Comprising a vast ensemble of photography, painting, drawing, and other two-dimensional media, the “Portrait Salon” is the focal point of the room and a highlight of the exhibition. The works are mounted salon-style, filling every bit of wall space from floor to ceiling. The salon-style display conscientiously references the Parisian salons of the 19th century but sheds any adherence to the academic uniformity they so ardently championed. Variety is the only theme here, and there’s certainly plenty of it, ranging from 17th-century Dutch portraiture to the photography of Dawoud Bey and Diane Arbus.

History Told Slant: Seventy-seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

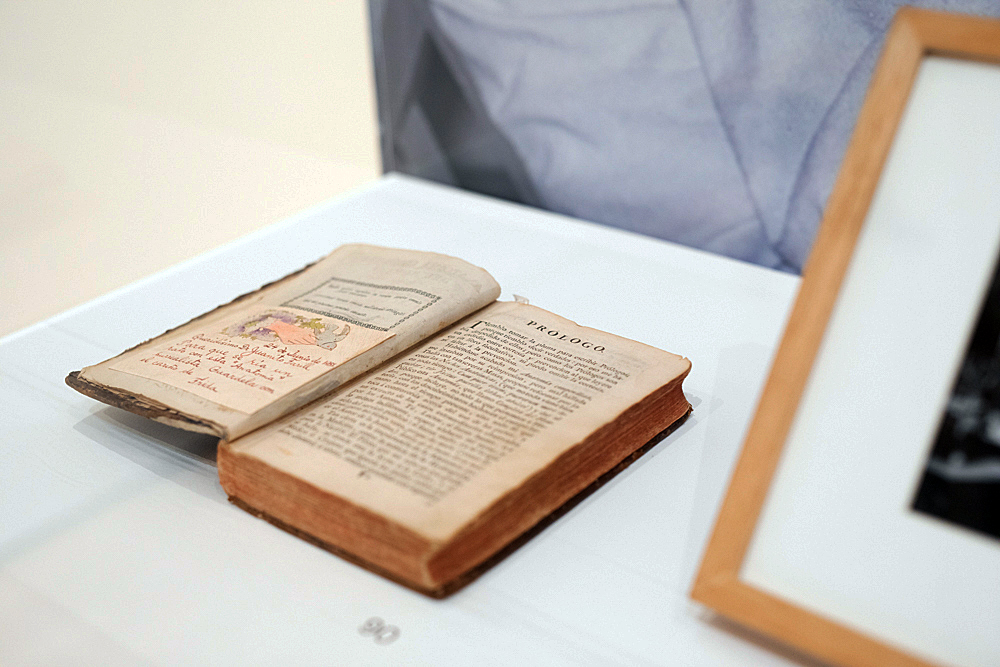

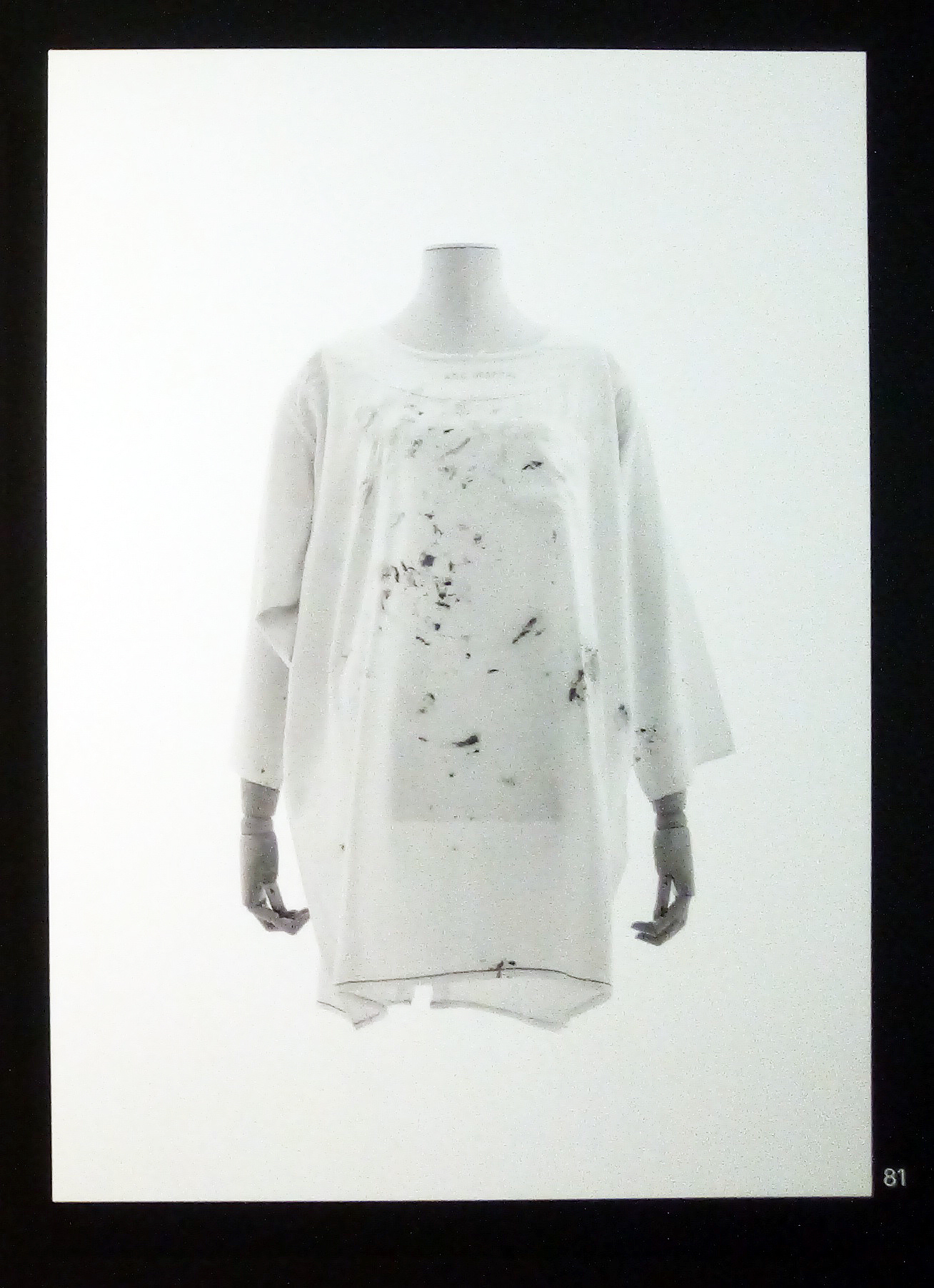

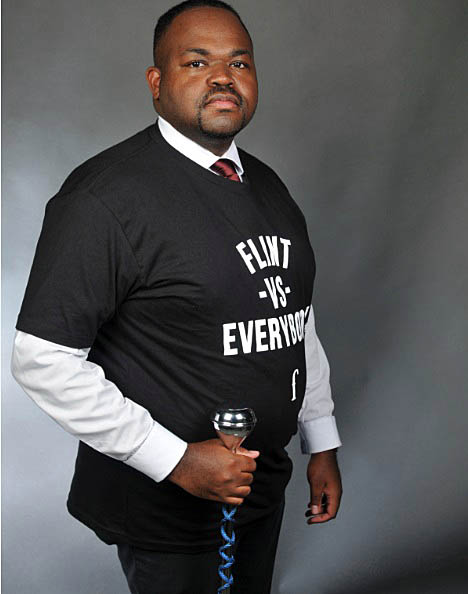

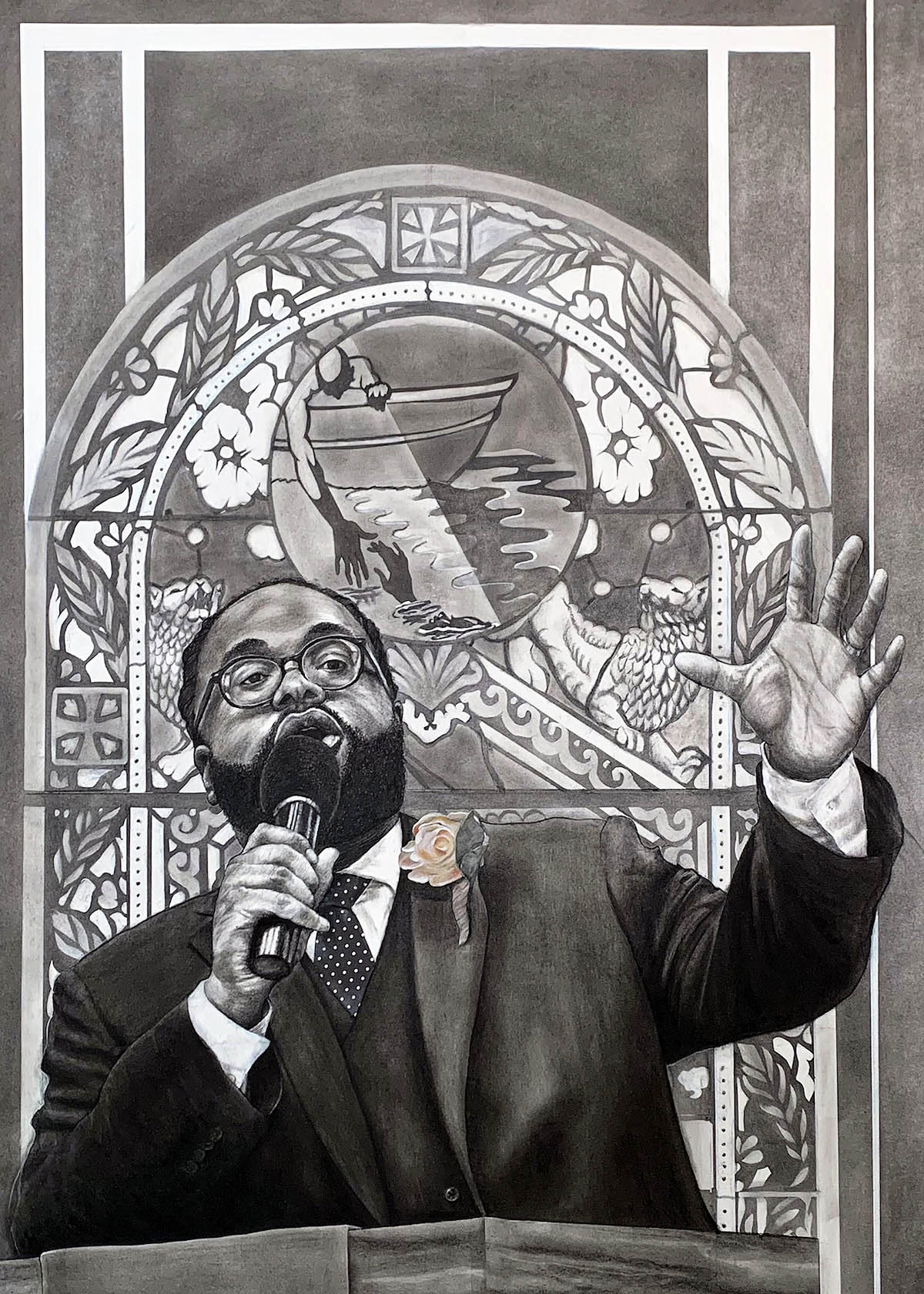

An adjacent gallery space addresses the theme of “Embodying the Divine,” and features both religious art and art inspired by religious art. Unlike the wall of portraits, these works are given more breathing room. Western and Non-Western traditions are represented, ranging from Christian devotional paintings (including Francisco de Zurbarán’s painting of St. Anthony), an ensemble of illustrated pages from an 18th-century copy of the Bhagavata Purana, and a few surprises. One of these is a characteristically large painting by Kehinde Wiley; taking his inspiration from a Baroque-era sculpture of a martyred St. Cecelia, here Kehinde replaces Cecelia with a lifeless black male, the circumstances of whose presumed death/martyrdom is not revealed to the viewer. Kehinde Wiley has produced an impressive and immense body of work based on re-imagining canonical works of Western art, and there likely isn’t a better artist to include in a show that reconsiders art history through a more inclusive and equitable lens.

History Told Slant: Seventy-seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

History Told Slant: Seventy-seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

Mimicking the exhibit’s portrait wall is an equally impressive salon-style display featuring paintings, photographs, and prints loosely based on the theme of landscape art (some still-lives, several cityscapes, and even some completely abstract paintings are included here, but they all seem to support the theme). As with the portrait gallery, here the Broad flaunts the stylistic, geographic, and chronological scope of its collection. Perhaps the most well-known of these works is actually a seascape: viewers will surely recognize The Great Wave off Kanagawa, Hokusai’s famed Edo-period woodblock print. There’s photography by Ansel Adams, Chinese vertically-oriented scroll painting, Inuit lithography, and even two paintings by Michigan’s own Mathias Alten, who spent much of his life painting Michigan’s landscapes and lakeshores. In the center of the gallery space, a sculpture by Alexander Calder, Sunrise over the Pyramid, playfully broadens the boundaries of what we might ordinarily consider a landscape.

History Told Slant: Seventy-seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

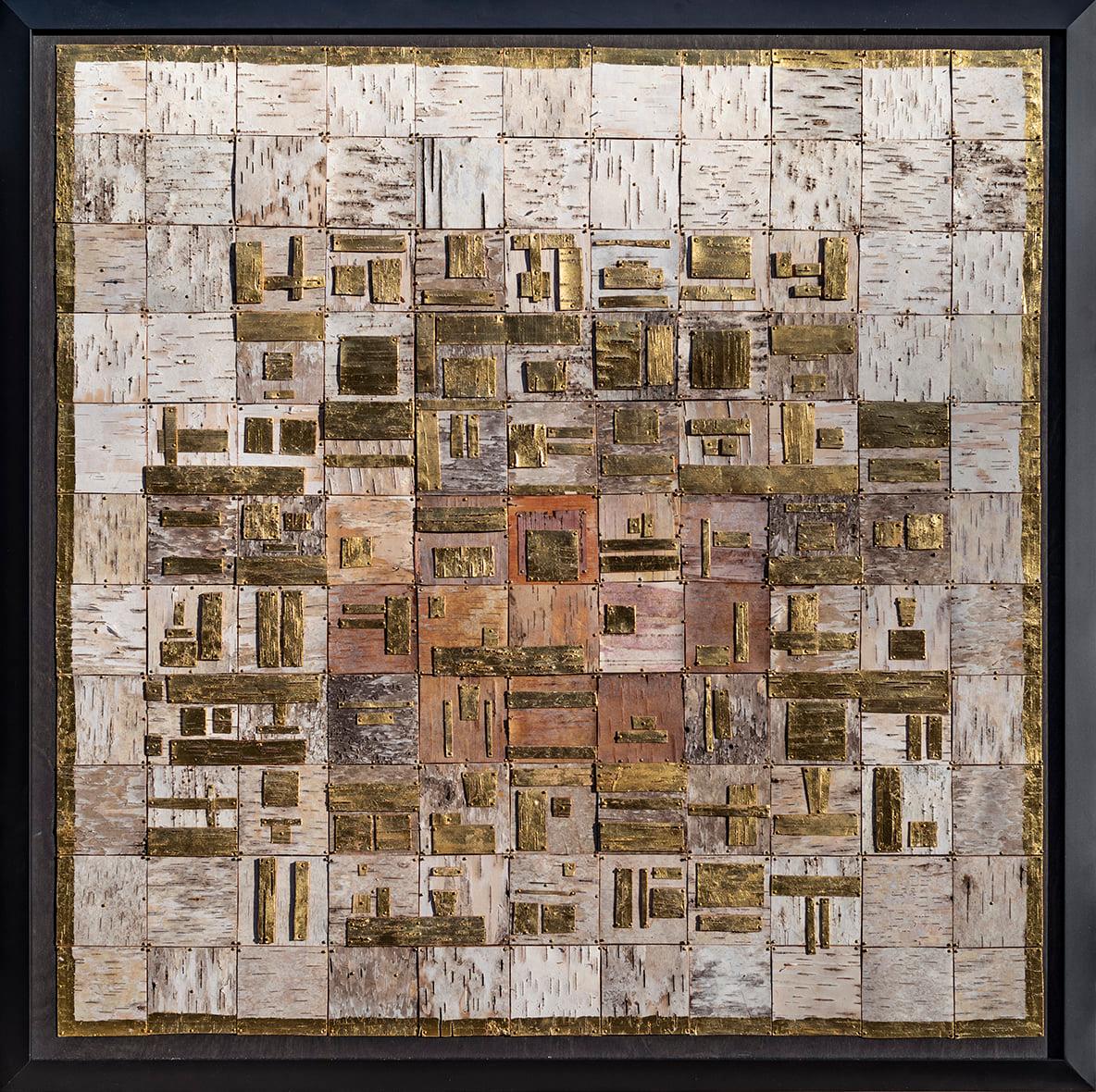

In several instances, works by contemporary artists engage in direct dialogue with art from the ancient past. In her works To the Unknown Migrant and Eternal Pilgrimage, contemporary Mexican artist Betsabeé Romero engraves tires with traditional Mexican figurative imagery, juxtaposing an emphatically modern substance with historic cultural symbols. Just a few feet away is an ensemble of small Mayan sculptures, some of which come from as early as the 8th century. If we’re giving an award to the oldest work in the show, however, perhaps it should technically go to Daniel Baird’s Moment II, a wall-mounted sculpture made from a 30-million-year-old fossilized tortoise shell.

History Told Slant: Seventy-seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Aside from introductory remarks explaining each section of the exhibit, there’s little expository text accompanying the art, and most of these works are allowed to simply speak for themselves. It’s difficult to recommend highlights from the show, since the entire exhibit comprises highlights from the Broad’s collection, which contains nearly 5,000 years’ worth of artwork. There’s a smattering of everything, and artists with significant name recognition are paired alongside new and emerging contemporary talent. Since its construction a decade ago, the Broad has largely functioned as an emphatically contemporary art museum and an excellent one at that. But it’s nice to be able to once again, and all in one place, see new artwork join forces with so many of the old staples that graced the walls of the old Kresge Art Museum; it feels very much like being reunited with old friends.

History Told Slant: Seventy-Seven Years of Collecting Art at MSU is on view at the Broad Art Museum through August 7, 2022.