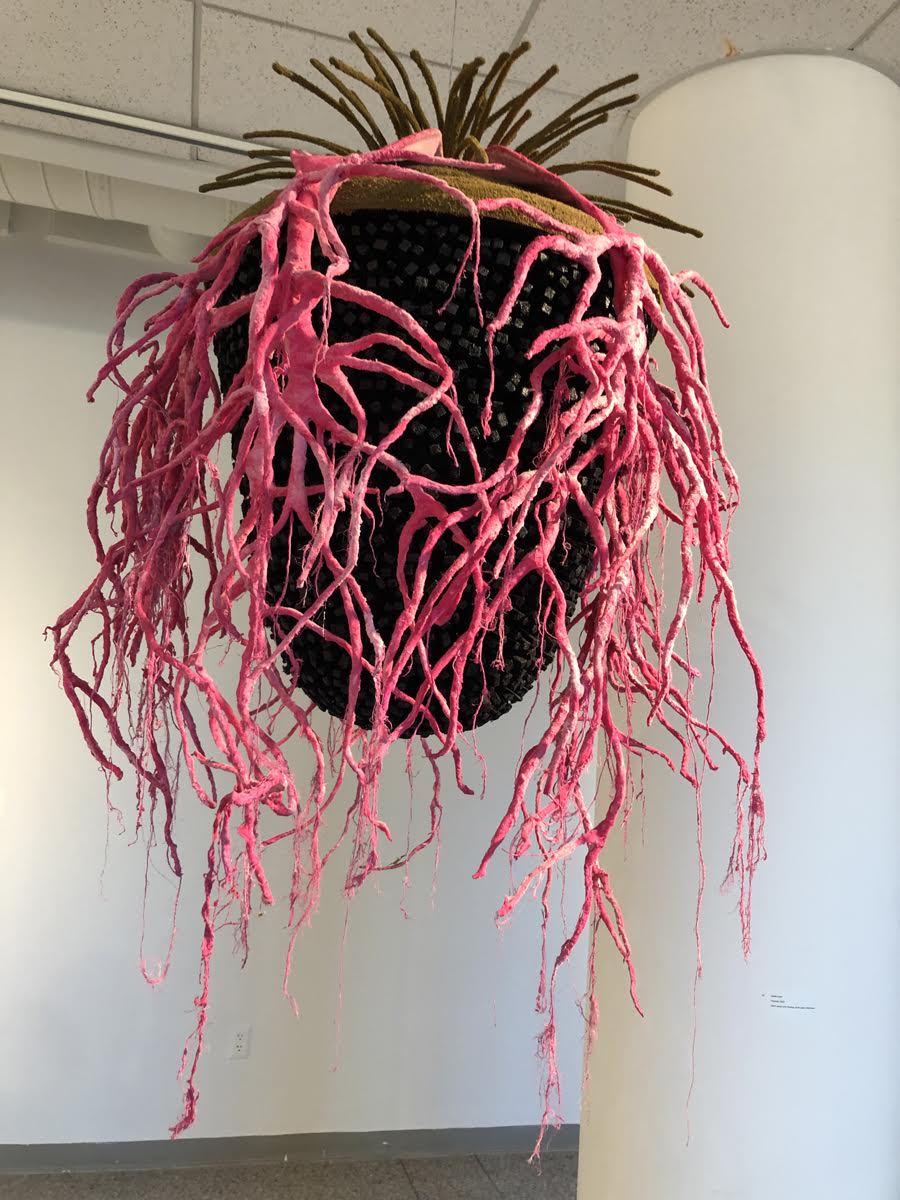

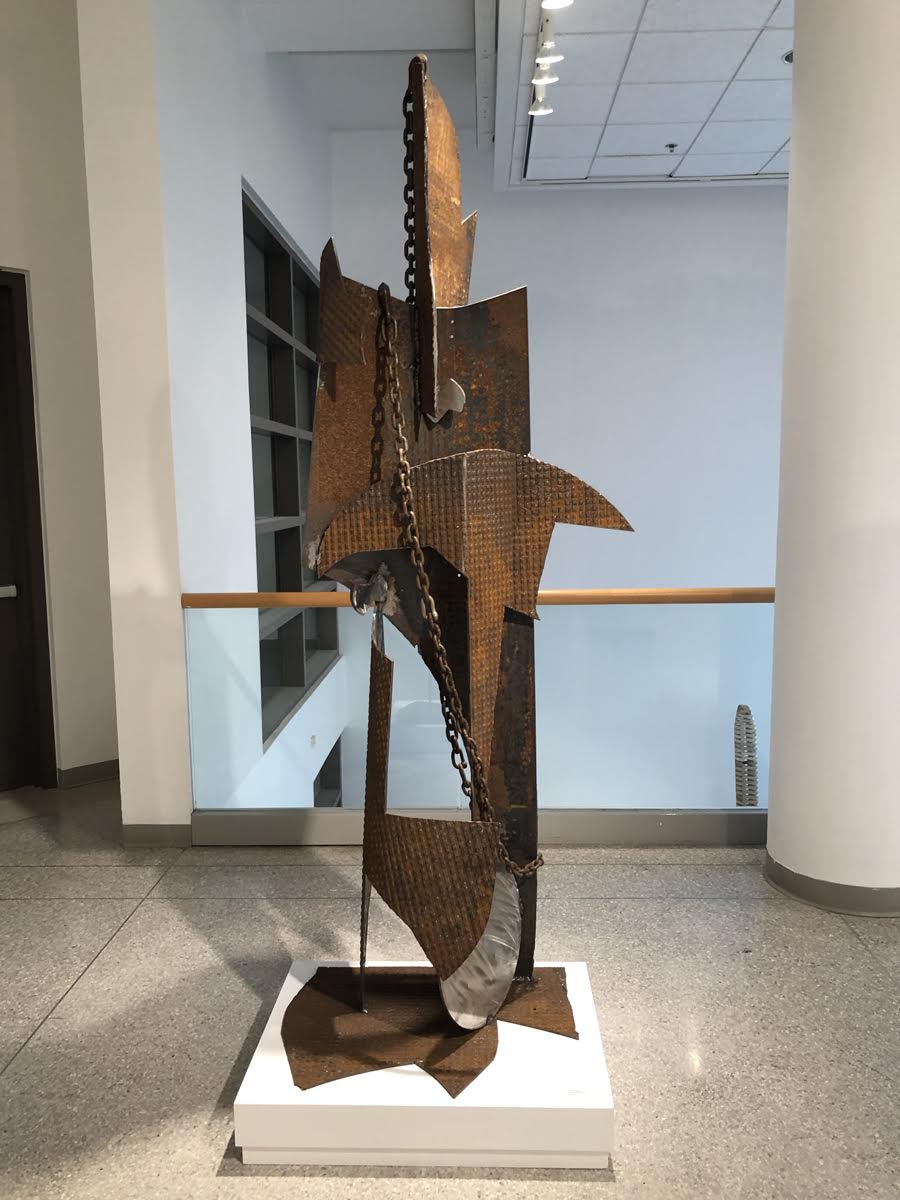

Opening night reception for “Semillas” at Playground Detroit, October 22, 2023. Photo by John Sippel

Human beings are a storytelling species–it’s how we make sense of the world. In his solo exhibition “Semillas,” now at Playground Detroit until November 19, Ivan Montoya has painted an idealized origin story as he tries to make sense of his adopted country while also preserving ties to his Hispanic cultural heritage. Based on early memories of his birthplace in Chihuahua, Mexico, and his immigrant childhood in the U.S., the paintings in “Semillas” tell a story of transition and displacement, loss and possibility.

The exhibition title is inspired by the Spanish proverb “hoy semillas, mañana flores,” which can be translated “seeds today, flowers tomorrow.”

That Montoya is aware of the provisional nature of the story he is telling is evident in the storybook quality of the 17 paintings in the exhibition. Along two walls of the gallery, he has strung together several of his artworks in an implied narrative, each sequence bookended by decorative floral panels as if they are the covers of some mysterious folk tale. The paintings, while presented in a line that suggests a series of events, are stand-alone images that might be disjointed childhood memories or mythical scenarios drawn from dreams.

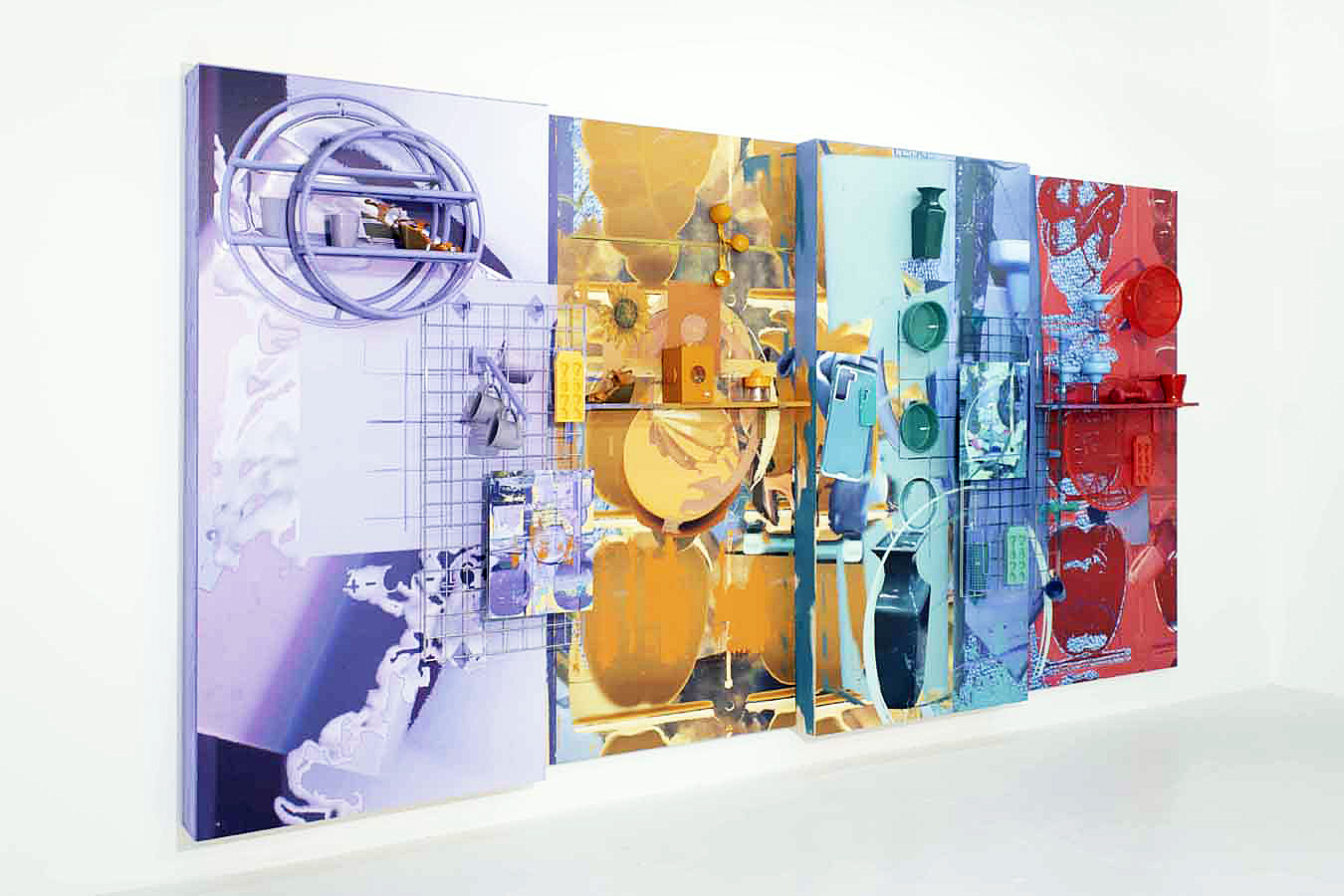

Ivan Montoya, Setting of the Altar, 2022, acrylic on birch panel, 24” x 36” photo courtesy of the artist and Playground Detroit

One row of paintings includes Setting of the Altar, among others, and seems to center on scenes of more-or-less harmonious community life. The compositions are bathed in warm colors that give an idyllic air to the timeless Edenic visions. Montoya avoids placing the scenes within a recognizable time and place—they are once-upon-a-time visions that are no place and every place, but they exist in the artist’s imagination most of all.

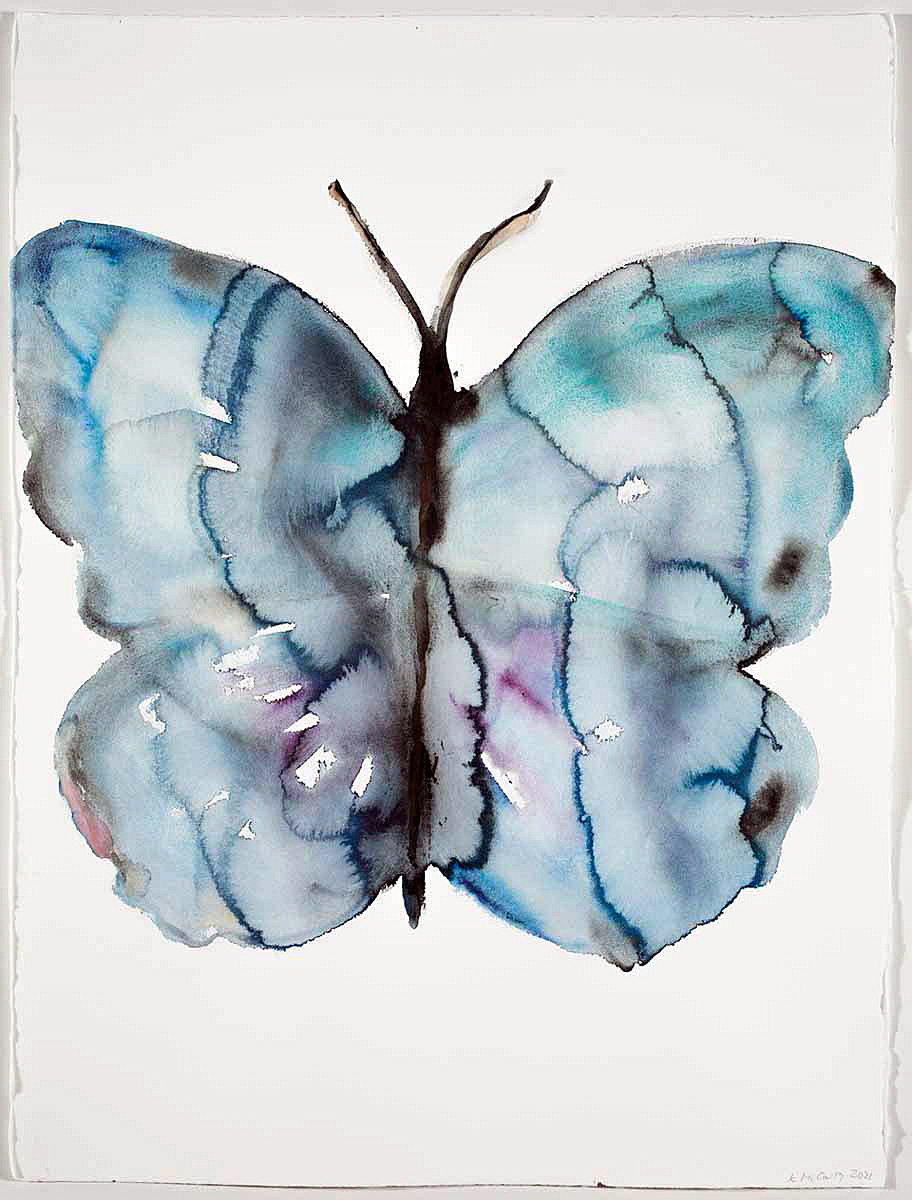

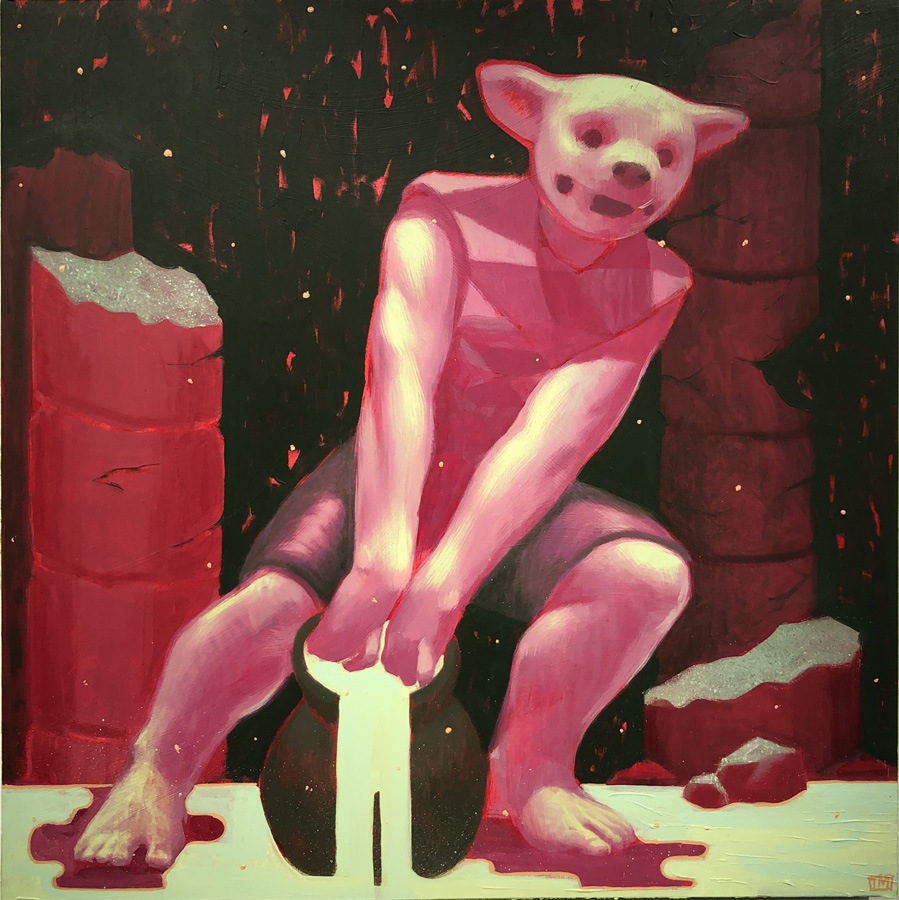

Ivan Montoya, Inciter, 2022, acrylic on birch panel, 24” x 24” photo by K.A. Letts

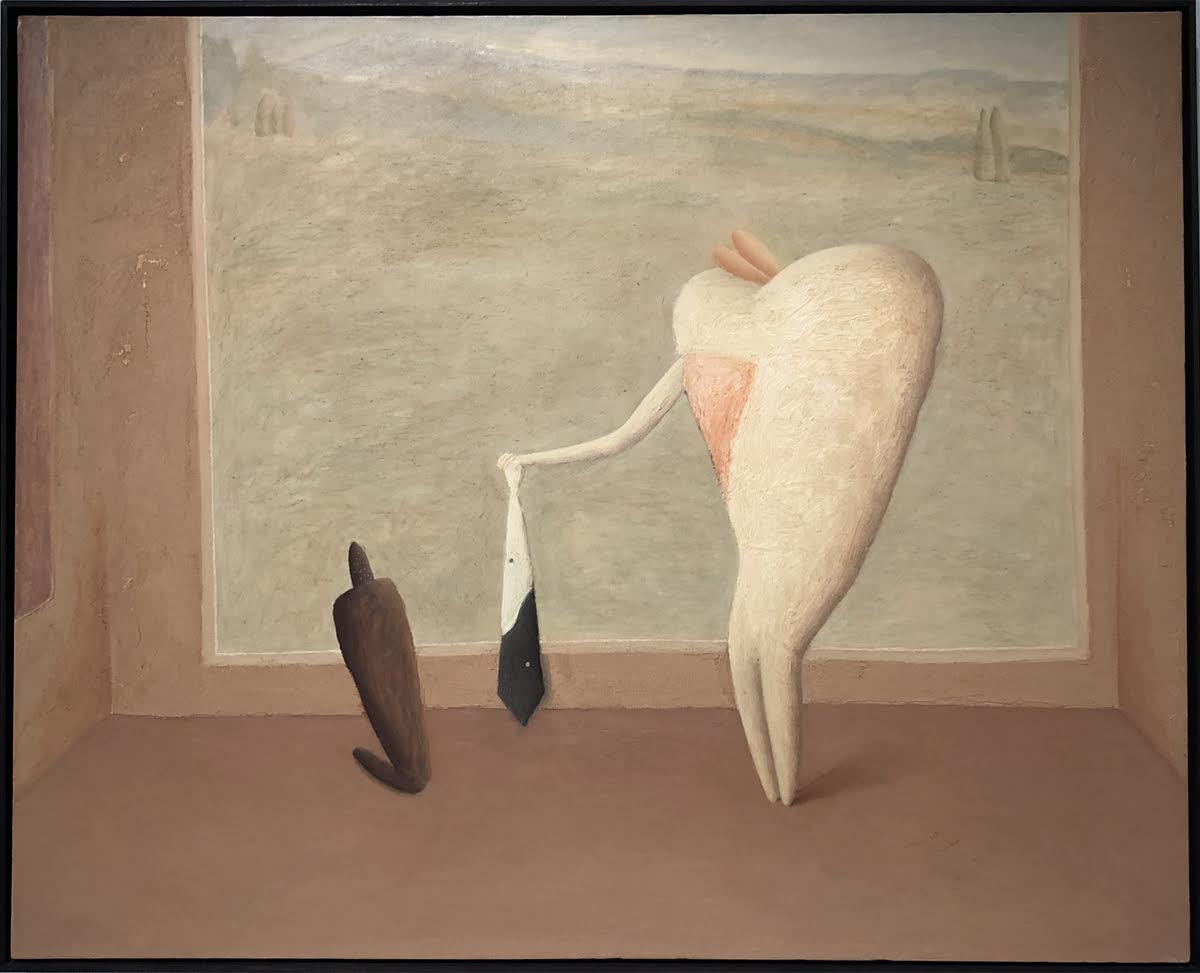

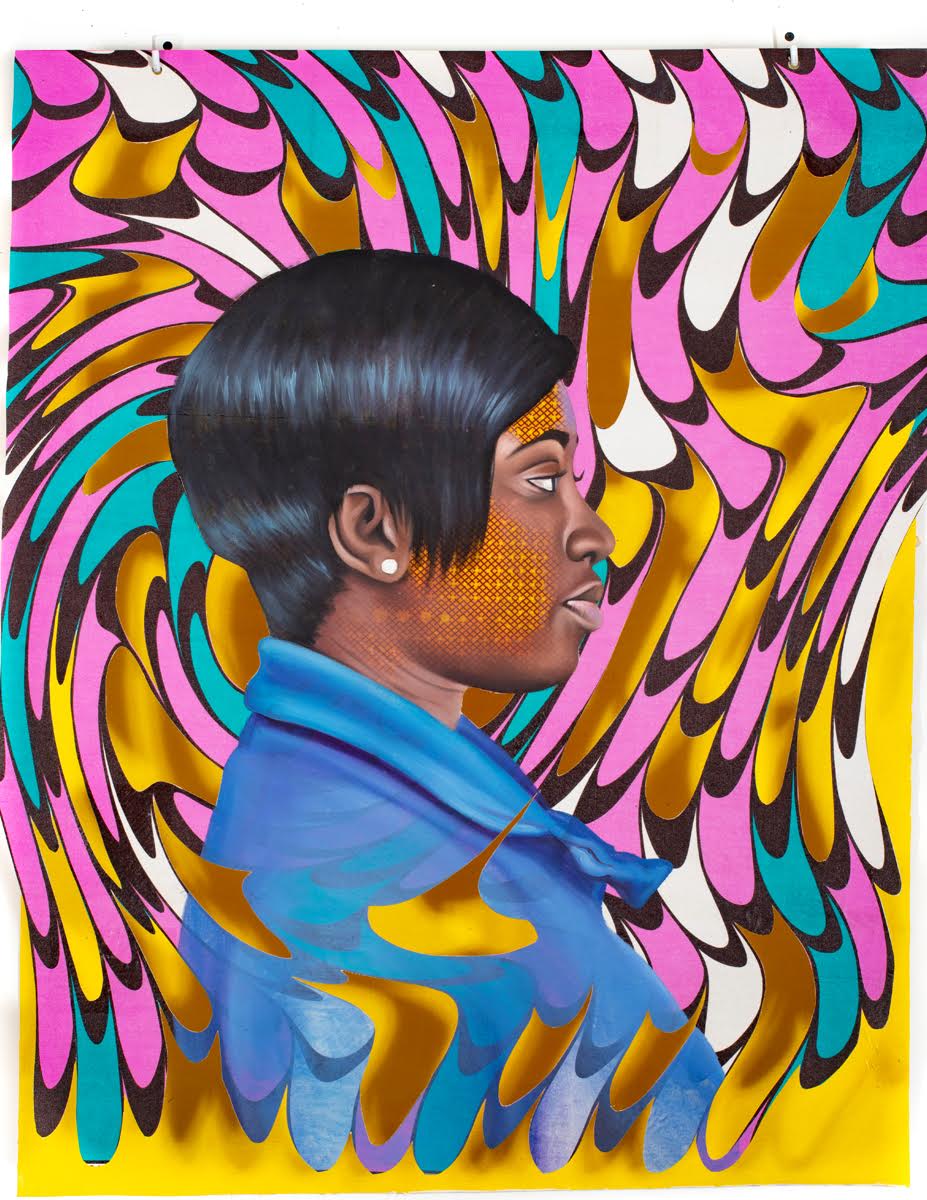

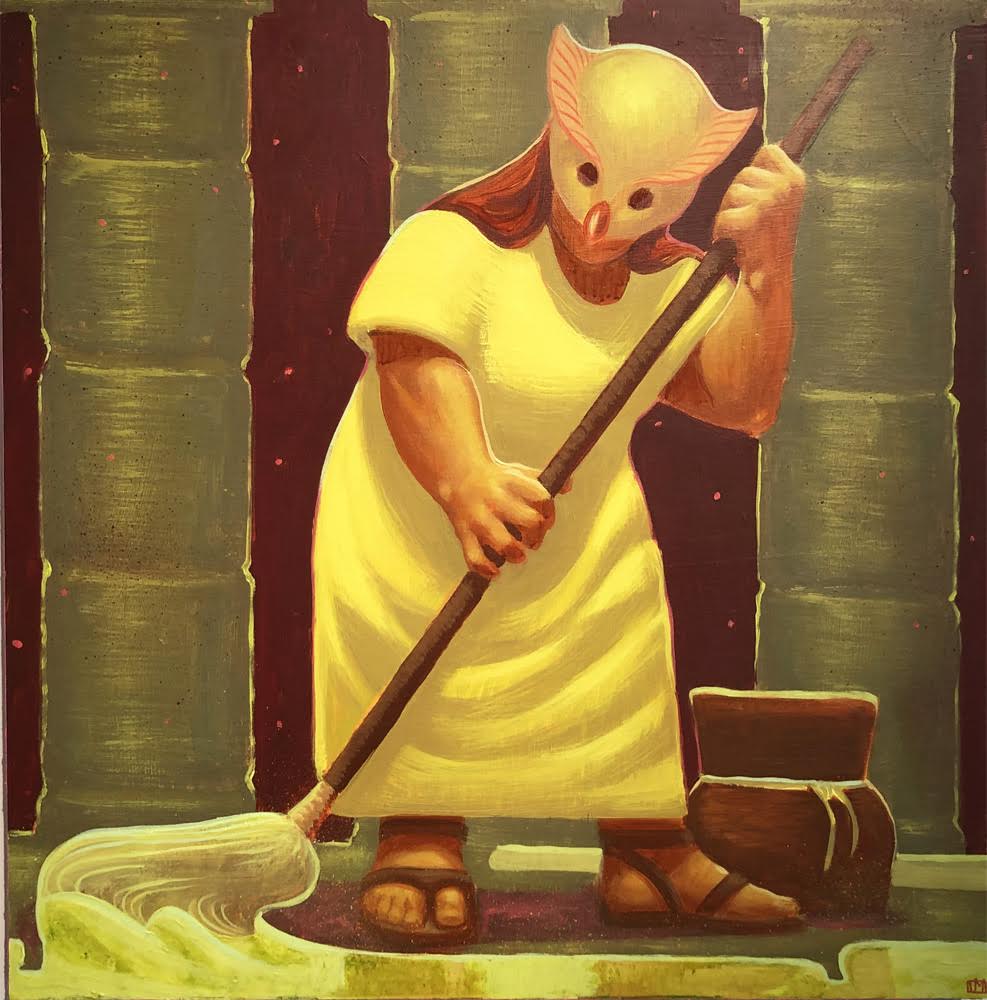

The warm, late afternoon light of Montoya’s family-centered paintings gives way to mysterious nocturnal illumination in another loosely narrative series on the opposite wall of the gallery. Once again framed by floral panels, this line of images takes us in a different, more archetypal direction. Inciter and Guardian, a pair of paintings that depict two single but related figures set among the pillars of what appears to be a monumental temple structure at night, imply–but don’t insist–on a story. The Inciter is an impish trickster character, caught in the act of spilling and breaking, all energy and mischief. The companion painting, Guardian, is occupied by a tired-looking maternal figure wearily cleaning up Inciter’s mess. Like the two paintings flanking it, the central painting, Latchkey, features two masked, child-like figures that convey an air of playful mystery.

Ivan Montoya, Guardian, 2022, acrylic on birch panel, 24” x 24” photo by K.A. Letts

The painting that most clearly references the immigrant experience is found in Paladarium, where a man and woman carry a large glass vessel through a snowy landscape. Two axolotls are contained within. The axolotl is a species of salamander native to Mexico, but which these days is mostly native to research labs, its native habitat having been degraded by urban development and climate change. The species is known for its almost miraculous ability to regenerate damaged limbs, as well as for the fact that it has both lungs and gills. Legend has it that the salamander represents the Aztec god of fire and lightning, and clearly it (along with the jaguar) has significance for Montoya as a metaphor for his dual identity as an immigrant and an American. He explains, “My immigration definitely is something I drew from for this [painting], but more specifically I intend to shed light on the hope behind relocating or changing environments. Paladarium refers to a tank that replicates the biome in which reptiles and amphibians live. This piece references the fact that some creatures only grow as large as the environment that they live in allows them to. Which is essentially many immigrants’ purpose for emigrating.”

Ivan Montoya, Descanso (Rest), 2022 acrylic on birch panel, 24” x 36” photo courtesy of the artist and Playground Detroit

Montoya paints in a straightforward figurative style, with surfaces that are signboard matte on wood panels. No obvious painterly flourishes mediate our experience of the light-filled compositions rendered in saturated colors. The pictorial space of each painting is often filled and activated by two or more stocky figures drawn in a manner reminiscent of mid-twentieth-century Mexican painters like Diego Rivera or Jose Clemente Orozco. Like these artists, Montoya delivers a strong sense of the 3-dimensionality of the figures in his compositions, and there is often an underlying archetypal subtext. But where Montoya’s artistic forebears draw inspiration from the political upheavals of their time, Montoya’s preoccupation is with a more personal journey.

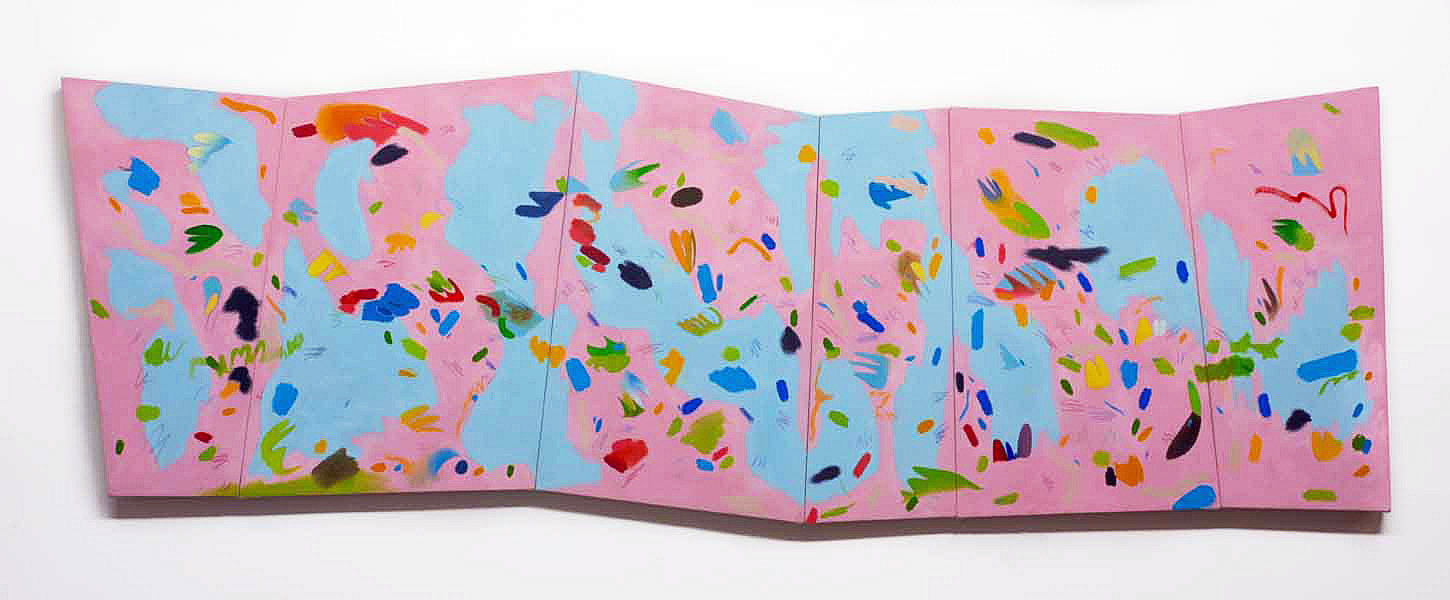

“Semillas” gallery installation, photo courtesy of the artist and Playground Detroit

The artist credits an eclectic group of Mexican artists as further influences in the development of his style. The surrealist painter Rufino Tamayo, the expressionist Jorge Gonzalez Camarena and the academically trained Saturnino Herràn have all influenced his work in subtle ways. He pays particular attention to Rufino Tamayo’s surreal, earthy humanist themes and the idiosyncratic style that sets him apart from the more political work of his contemporaries. Montoya has studied, too, the pre-Hispanic motifs and reliefs found in Mayan or Aztec culture, combining all these influences in pursuit of an authentic Mexican-American cultural identity.

In his debut solo show at Playground Detroit, Ivan Montoya has clearly mapped out his path toward a worldview and an art practice that makes space for mystery and spirituality while allowing scope for both his American experience and his Hispanic heritage. Whether he is rendering the warm light of a late afternoon in an orchard or moonlight shining on a luminous sea, this hybrid way of being becomes ever more clear in the artist’s work. Perhaps Montoya says it best:

“My cultural identity is the core of what I am trying to understand and make peace with. I’ve grown up in two worlds and I don’t always feel like I belong to one or the other too firmly. So to me, understanding how I’ve been molded by both is super important to how I communicate and create especially because of how many other people feel like I do.”

“Semillas,” gallery installation, preview dinner, photo courtesy of the artist and Playground Detroit

Playground Detroit presents Ivan Montoya’s solo exhibition “Semillas,” now on display until November 19, 2022.