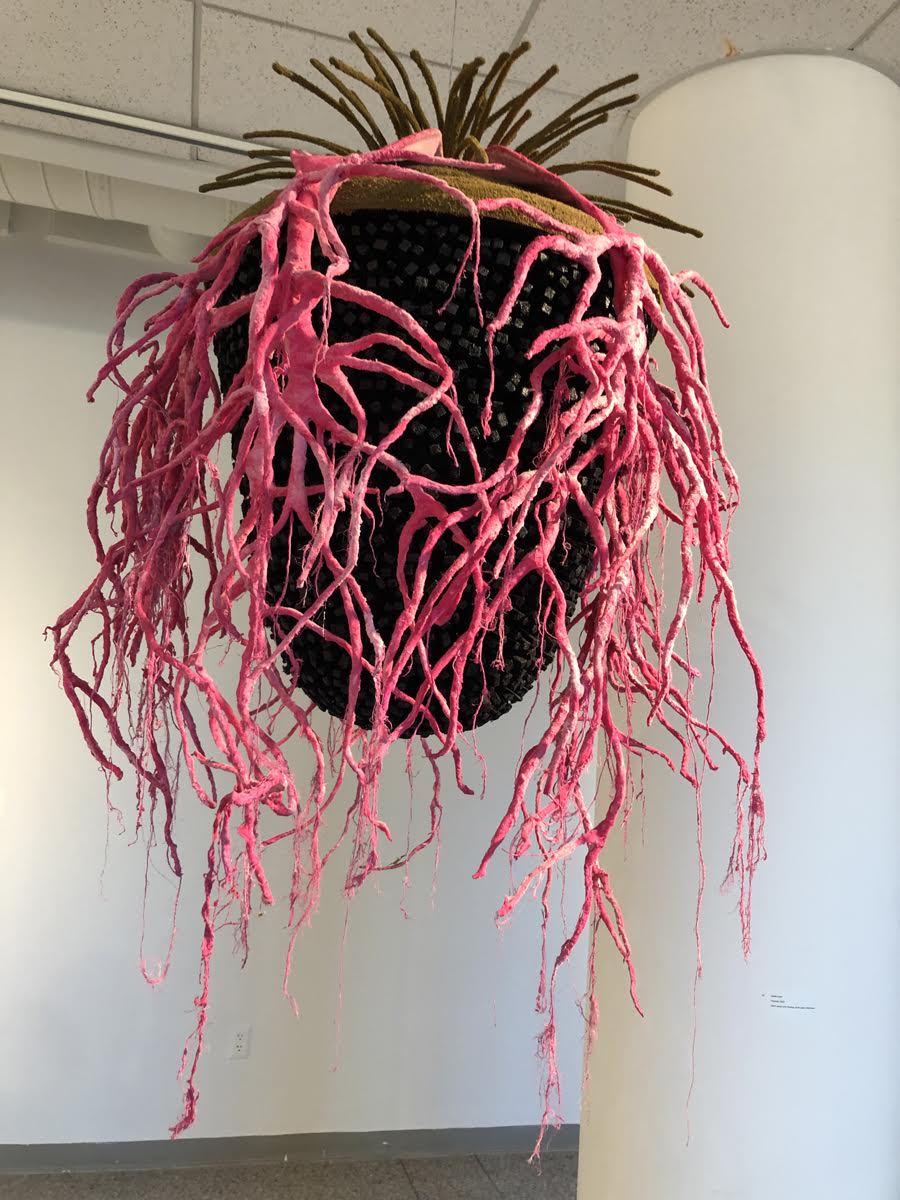

An installation shot of Concerning Landscape at Detroit Artists Market, up through Feb. 18. Image courtesy of Michael Hodges.

Over the centuries, the venerable landscape painting has evolved far from the Dutch masters who first perfected the genre — a fact underlined by the heterogeneous work in Concerning Landscape, up through Feb. 18 at both the Detroit Artists Market and the new Brigitte Harris Cancer Pavilion at the Henry Ford Cancer Institute in Detroit.

Curator Megan Winkel has adopted a refreshingly ecumenical point of view in pulling this together. Works range from Ann Smith’s intriguingly peculiar sculptures with their bunched reeds and dangling root systems to Carla Anderson’s photographic prints of geologic forms, including lyrically striated rocks in a spring in Yellowstone County, Wyoming.

A fan of the grand view? Not to worry. Concerning Landscape also embraces figurative vistas, like Helen Gotlib’s meticulous intaglio print, West Lake Preserve II, or Bill Schahfer’s lush photo study, Lagoon Life.

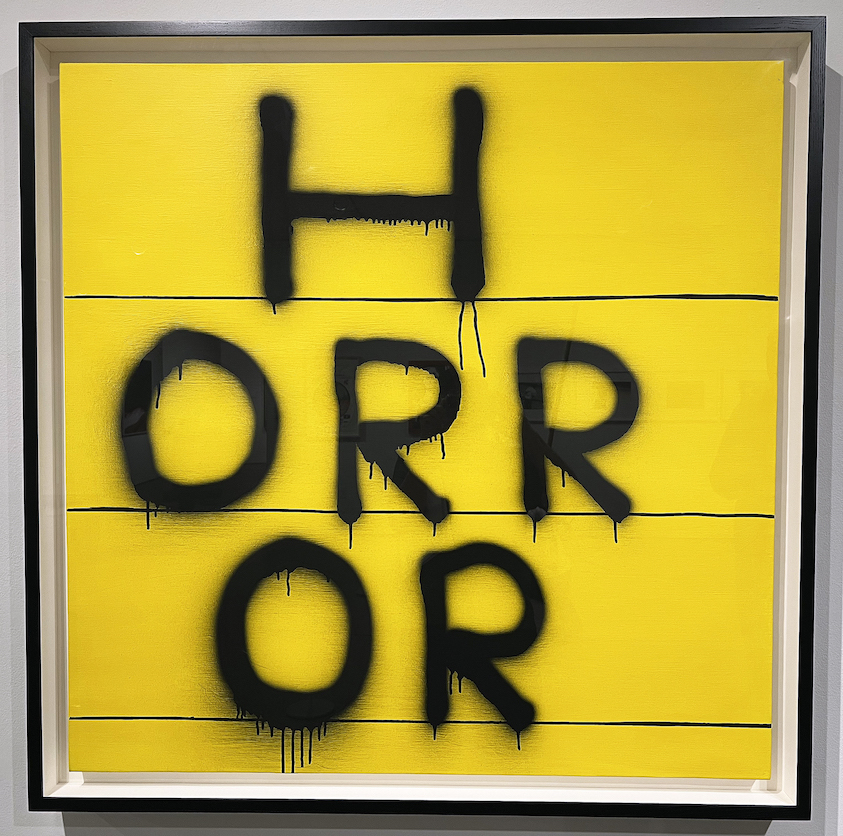

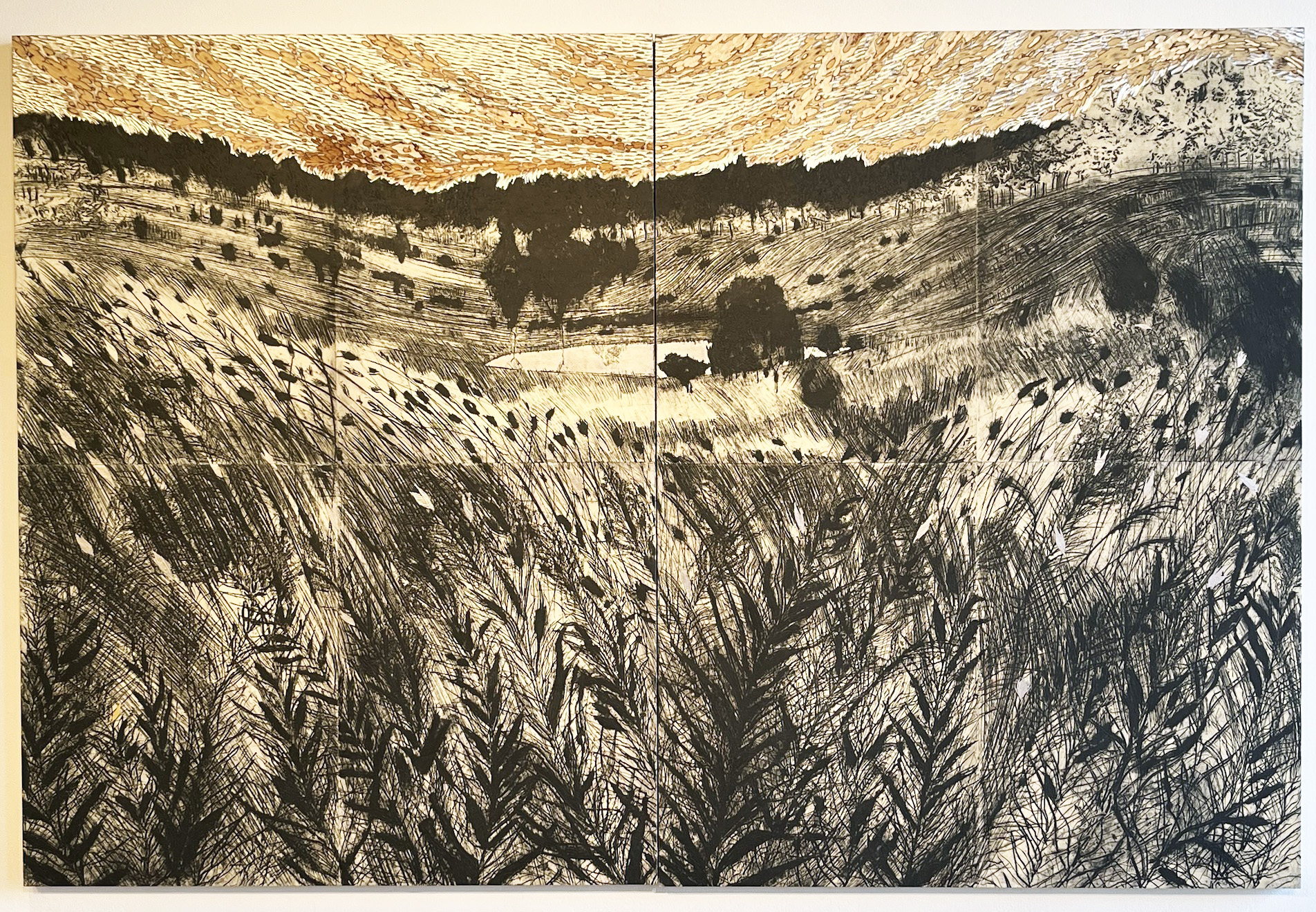

Helen Gotlib, West Lake Preserve II, Intaglio print, carved birch panel, palladium leaf; 2021. All Images courtesy of DAM

“West Lake Preserve” places the viewer right in the tall weeds, looking up a small valley to a pond and woods, a highly satisfying view. The large print’s divided into eight separate panels, and with the exception of a little dull orange at the top, it’s mostly a duotone essay in sepia and black. The photographic print, Lagoon Life, by contrast, stars a white ibis posing beneath a jungle crush of palm trees that all loom, menacingly, over the elegant bird’s head.

Winkel comes at all this curation from an interesting vantage point. She’s the manager and curator for the Healing Arts Program at Henry Ford Health Systems in Detroit, tasked with buying art for the sprawling medical empire. “Curatorial projects for me are mostly big buildings now,” she said, “and thinking about all the ways people can experience art when they’re not seeking it out.” The landscape, she adds, has understandably long found a home in medical centers given its generally soothing visions of a natural world far beyond the reach of the artificial light of the hospital ward.

Landscape as an art subject, of course, has a long, respectable history. Both the ancient Greeks and Romans enjoyed the genre, and the walls in upper-class homes were sometimes painted with pastoral views. But the status of the landscape plummeted in the Middle Ages, when religion elbowed every other art subject aside. Indeed, the natural world was reduced to a mere afterthought, and one with generally lousy perspective, to boot.

Things began to turn around in the Renaissance, particularly during Holland’s “Golden Age” in the late 16th and 17thcenturies, when an exquisite sensitivity to landscape and weather welled up in many studios, yielding in the best cases – van Ruisdael comes to mind — breathtakingly believable clouds and storm-tossed skies. Indeed, an online essay by the National Gallery of Art notes that “with their emphasis on atmosphere, Dutch landscapes might better be called ‘sky-scapes.’” (The Detroit Institute of Arts, by the way, has an outstanding collection of Golden Age Dutch paintings, well worth seeking out on your next visit.)

Catherine Peet, Looking Up from the Deep, Mixed media, 10” diameter.

The one piece in Concerning Landscape that gives van Ruisdael a run for his money is the vertiginous, gorgeous, Looking Up from the Deep by Catherine Peet, which you’ll find at the Henry Ford Cancer Pavilion gallery. This delicate sunrise or sunset-tinged cloudscape feels like it should be peering down at you from the dome of some state capitol, an impression strengthened by its circular frame.

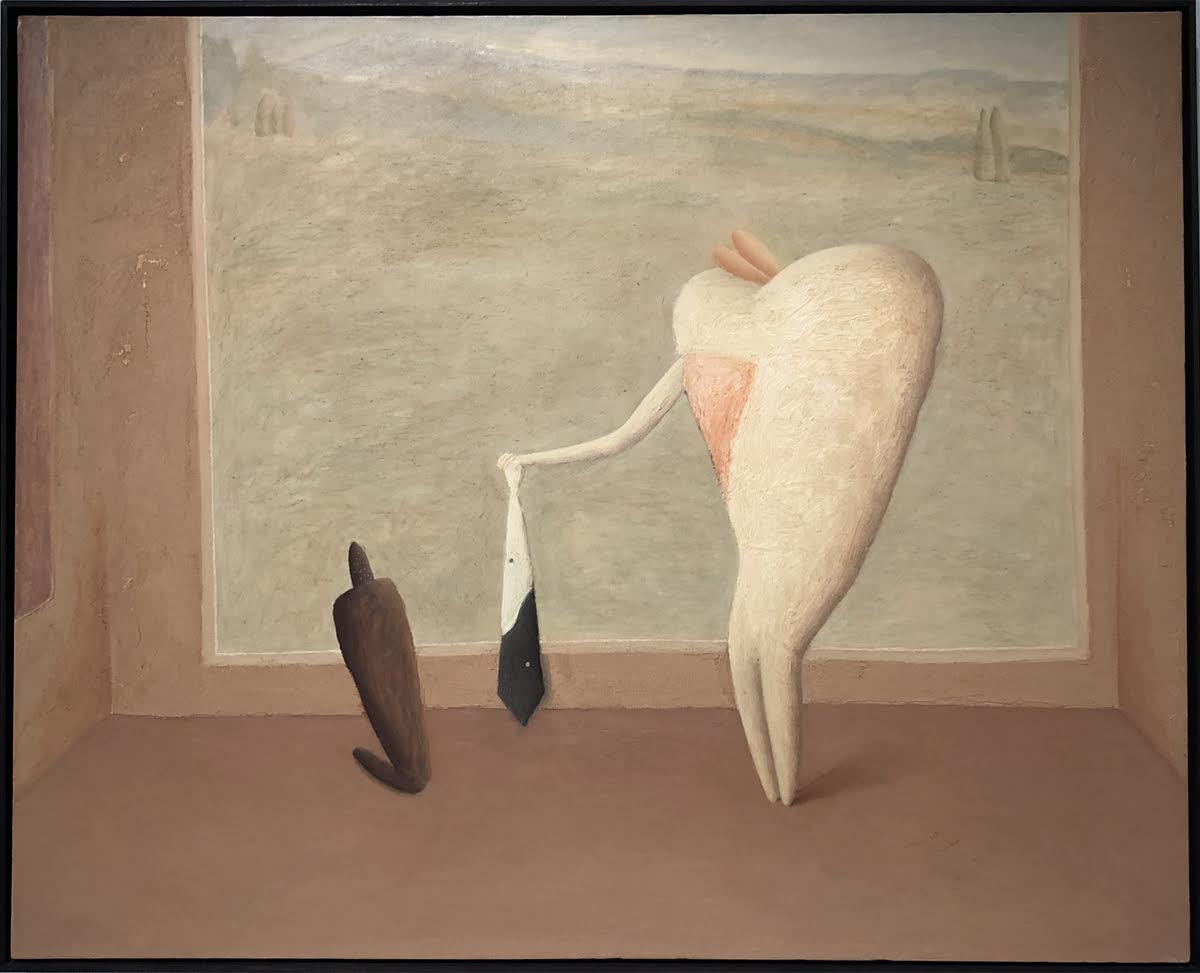

Sharing some of the same warm tones but at the far abstract end of the spectrum is Carole Harris’ mixed-media Desert Flower. The 2015 Kresge Artist Fellow has constructed an overlapping stack of hand-made fiber sheets that read like thick, highly textured paper, in colors ranging from cocoa to an alarming red peeking out beneath all the others.

The simplicity of this particular conceit is striking, as is Harris’ ability to make real drama out of colors that only emerge as narrow strips visible beneath the warm brown sheet on top. That Desert Flower pushes the boundary of “landscape” goes without question – so, too, the fact that it kind of knocks the wind out of you.

Carole Harris, Desert Flower, Fiber, 2023

Russian transplant Olya Salimova, currently on a one-year BOLT Residency with the Chicago Artists Coalition, gives us something entirely different with her Body into Dill, one of the most original and daffy conceptions in the entire show. The centerpiece of this photograph is a rectangular garden space – disturbingly, about the size of a grave – that’s dug into the patchy lawn of some unpretentious backyard. Metal garden edging sunk in the turned-up dirt sketches a simple human shape, rather like police outlines of dead bodies on the sidewalk. Within that human-like enclosure, someone – Salimova? — has planted dill weed.

Its obvious imperfections are part of what makes this image so compelling. The yard clearly needs work, and the plantings in the “body” are scattered, newly dug and unsubstantial — apart from some vigorous leaf action filling up the head.

Olya Salimova, Body into Dill, Photography, 2021.

For those who enjoy a little disorientation in their photography – And when well done, who doesn’t? – Jon Setter’s collection of a half-dozen large prints, all up-close shots of building details, is a delight to behold. Each reads as an abstract design in 1920s Russian Constructivist mode. But in one case you’re looking at parallel diagonals on the late, lamented Main Art Theatre in Royal Oak, and in another, the Detroit Free Press building downtown on West Lafayette. As a group, these deliberately confusing framings are both mischievous and fun to examine.

Jon Setter, Purple and Gold with Shadow (Detroit Free Press), Archival pigment print, 2021.

Finally, Scenic Overlook 2 by Sharon Que, an Ann Arbor sculptor who also does high-end violin restoration, might remind you of a minimalist diorama minus the glass case. On a simple wooden shelf, Que’s sacked two smaller pieces of wood topped by a chalky white boulder or peak – part of the fun is the uncertainty — next to which sits a big, black, bushy… something.

Let’s stipulate that the white form is, indeed, a mountaintop. Call the spiky black, roundish thing next to it a plant, and you’ve got a surprisingly convincing perspective study of a bush and a white peak far, far in the distance – never mind its actual proximity in the assemblage.

Is it weird? Is it oddly compelling? Yes and yes.

Sharon Que, Scenic Overlook 2, Wood, magnetite, paint; 2016.

Concerning Landscape at Detroit Artists Market, up through Feb. 18.