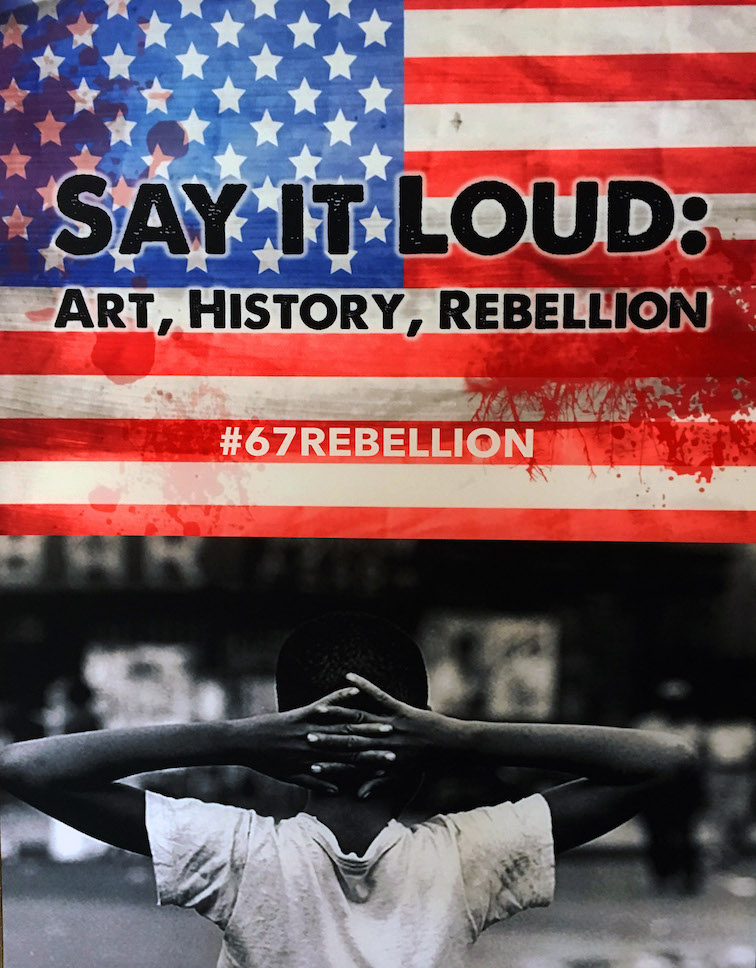

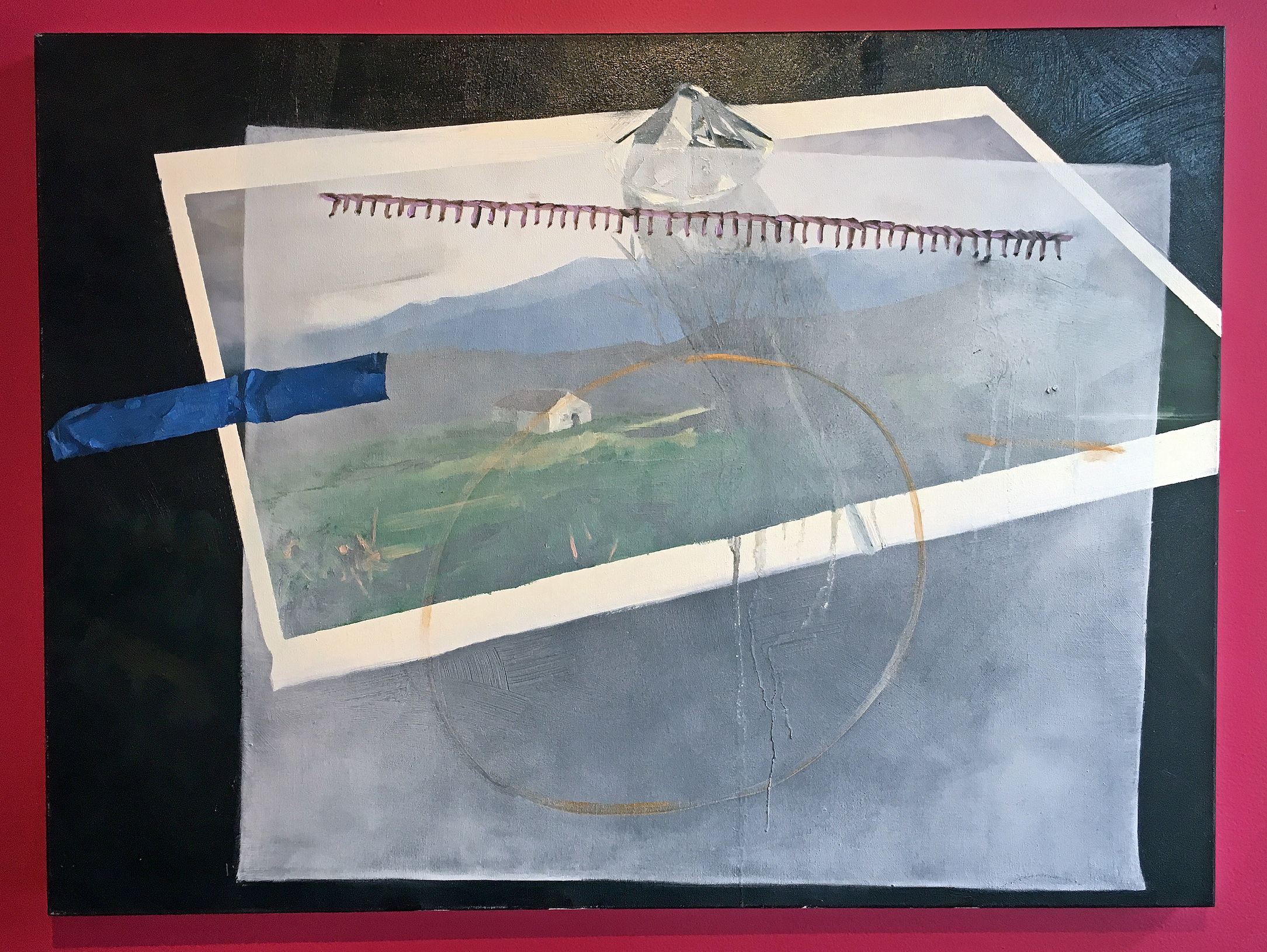

An exhibition, Ethics of Depiction: Landscape, Still Life, Human opens at Oakland University Art Gallery

Oakland University Art Gallery, Ethics of Depiction: Landscape, Still Life, Human, Installation Image Courtesy of OUAG, 2017

Rather than a Detroit-based solo artist or group show, Dick Goody, Chairman of the Department of Art and Art History, and Director Oakland University Art Gallery has curated an exhibition that draws on artists from various parts of world that provide an experience in imagery that questions fantasy, deception and truth. Fueled by contemporary image making, the exhibition is a collection of twenty-one artists ranging in gender, location, age, and location, providing artwork that includes photography, video, painting, and drawing. It could not be more diverse.

Goody says in a statement, “These works represent something just short of an inundation of content, and the presentation— “salon style” — affirms the idea that kaleidoscopic subject matter is enriching and arouses curiosity about the way in which contemporary artists use data and themes in their work to create a reflection of their lifespan on earth. The ethos of the exhibition sees parallels with the cabinets of curiosities from the past. Like the inquiring viewers of old encountering astonishing collections of objects, we today also experience a primary emotional connection to this type of work because its meaning is self-evident. Concurrently, the viewer’s entry point into these pictures is unclouded by unfamiliarity with Contemporary art. Anyone can find their way into these accessible depictions and explore the familiar, the strange, the formalistic and the conceptual stance of each image. But even using the phrase “conceptual stance” creates an unnecessary barrier between the viewer and the images. Perhaps it is much better to say “poetic stance.”

Richard Mosse, The Man Who Sold the World, 2015, digital c-print, 28 x 35″ Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

This image, The Man Who Sold the World, by Richard Mosse, an artist from Ireland, captured on infrared film, is shot in the Congo and feels like an ethnographic recording of workers, while moving away from a truthful depiction of the landscape. The reality of the image raises more questions than it answers.

Mosse says in a statement, “The subject of my work in Congo is the conflict’s intangibility, the irruption of the real beneath the generic conventions — it is a problem of representation. The word ‘infra’ means below, what is beneath. A dialogue about form and representation is one of the work’s objectives so I don’t think it’s a bad thing if people get hung up on the way Congo has been depicted, rather than what is being depicted.”

Jasper de Beijer, The Brazilian Suitcase (Part 2) #1, 2017, c-print 44.5 x 67 inches Courtesy of the artist and Asya Geisberg Gallery, New York

When I first experienced this image, I was taken back by my own thoughts of a place where a shrine was erected to the remnants of a Brazilian airplane. Again, this feels like an ethnographic image capturing a cultural act by what might be described as third world tribal individuals living in the jungle of Brazil. The images of Jasper de Beijer, an artist from the Netherlands, seem to want to break the perception of what we see as real, juxtaposed and complimented by our own experience and memory.

He says in a statement, “We experience reality through interpretation. For me, the most interesting feature of this process is that the interpretation of reality gains a new actuality, forming a corpus of imagery that becomes more and more disconnected from what actually took place. This is where images start to lead their own life — becoming more or less autonomous.”

Becky Suss, Hallway, 2017, oil on canvas, 84 x 180 inches Courtesy of The West Collection

The very large oil on canvas painting, Hallway, 84 x 180, by the artist Becky Suss from Philadelphia, dominates the entrance to the exhibition. This flat, neutral depiction of an empty house captures the mundane. If it were 6 x 12” on board it might pass as a postcard. The scale plays a major role in requiring the viewer to stop and study the contents, calling on our own memories and perceptions. In this work and for that matter all artwork, we bring our own experience to the moment and that is what can make all the difference. This idea works in the same fashion for all artwork.

Suss says in her statement, “In terms of the painting world, I do feel like sometimes there’s a dismissal of subject matter: “What is it? It’s just a room. It’s just a domestic interior. What does it mean?” There’s this idea that somehow it’s not terribly meaningful. But so much of our time is spent in these domestic spaces; they are where the scenes of our lives play out. Again, it’s something that’s undervalued. It’s taken for granted in some ways, like it’s an undeserving thing for a big painting to be made about.”

David S. Allee, Fireworks, 2016, dye sublimation metal print, 48 x 72 inches Courtesy of the artist and Morgan Lehman Gallery, New York

The photographic image, Fireworks, by David S. Allee, made me stop and study the large work, 48 x 72”, a dye sublimation on metal. I was first drawn to the image by the even lighting in the foreground and the sky, which led me to the question of exposure. Upon close examination, the viewer can observe movement in the detail of people, disclosing a long exposure time for the image. From the title one can assume we are viewing a group of people viewing fireworks, but the light source is intriguing and a mystery.

He says in a statement, “Structure, environments, spaces interest me for the stories they tell and layers of meanings they can describe. Photos of these forms usually require people to look closely, study, interpret and infer. If a viewer is drawn into an image of a built environment, they’re forced to use their imagination to understand it, make sense of it and in effect complete the image. The more an image has this relationship with people who view it the more successful I see my artistic process. I also have great interests in architecture and planning and a desire to build and create. Photographing these forms and framing them probably also helps to fulfill some of these desires.” After seeing the image, one can reimagine the landscape romantically, and change your perception of an experience. David S. Allee earned his MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

For this writer, this exhibition clarifies the role of a university gallery, especially with respect to their freedom to explore new ideas without the concerns of commerce. Goody at OAUG, focuses in his curatorial work, on educating his university students and raises the bar on exploration, dialogue, and meaning, not just for the students, but also for the Detroit Metro area at large.

Oakland University Art Gallery

Ethics of Depiction: Landscape, Still Life, Human runs through November 19, 2017