Sanford Biggers Subjective Cosmology opens at MOCAD

Sandford Biggers, From the Moon Medicin performance, All images Courtesy of Sarah Rose Sharp

The MOCAD kicked off their Fall program this weekend with an opening-night throwdown for Subjective Cosmology by Sanford Biggers on Friday, September 9, followed by an artist talk and walk-through of the exhibition on Saturday, September 10. While most art exhibitions feature an opening celebration, the events unfolding around Subjective Cosmology, including a performance by Biggers’ musical group, Moon Medicin, were integrated with work on display—and a continuation of Biggers’ larger body of work—acting as a kind of charging ceremony, or christening of sorts, for the show.

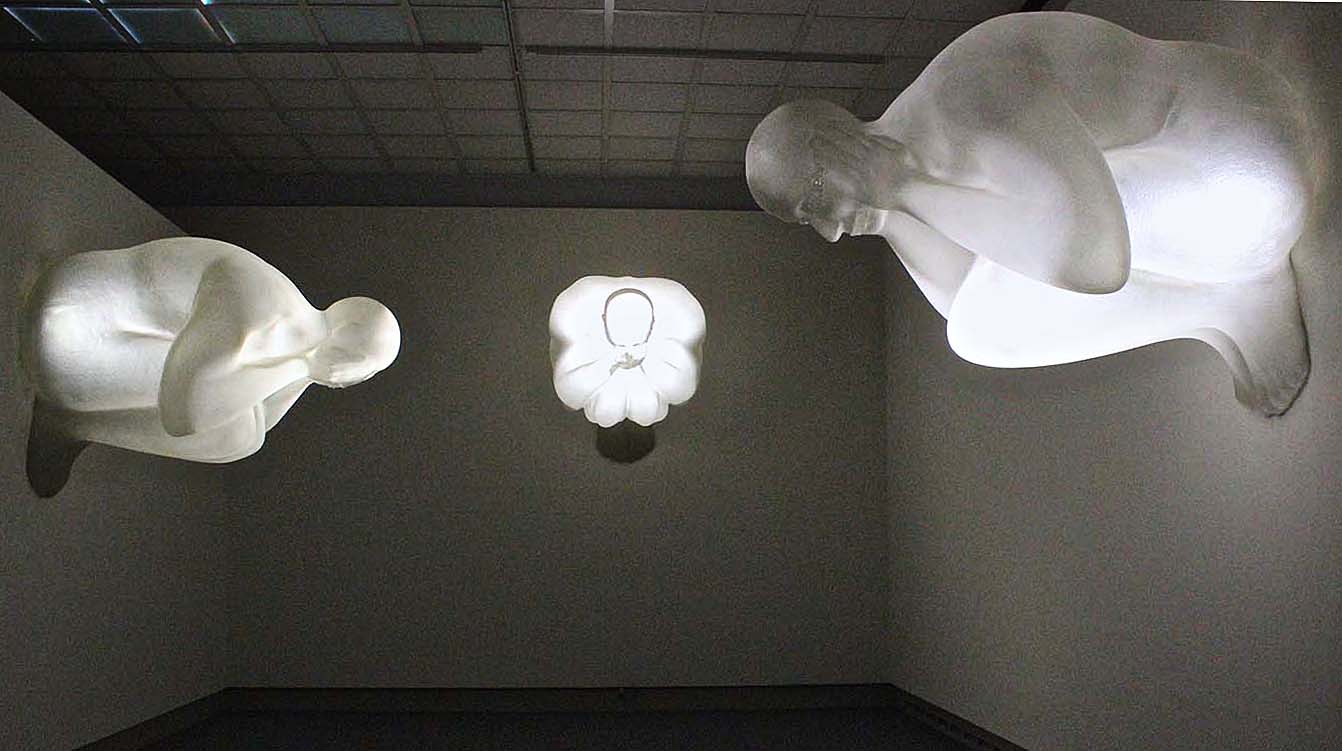

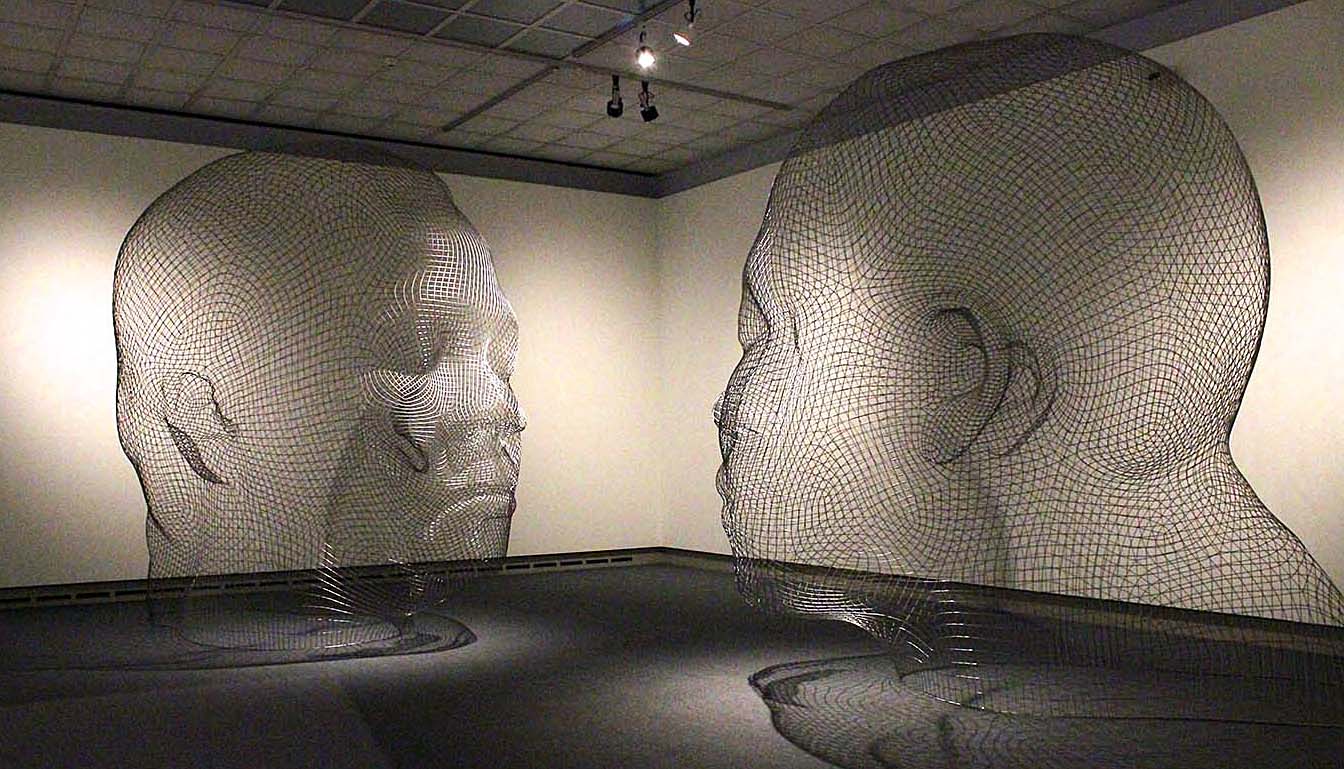

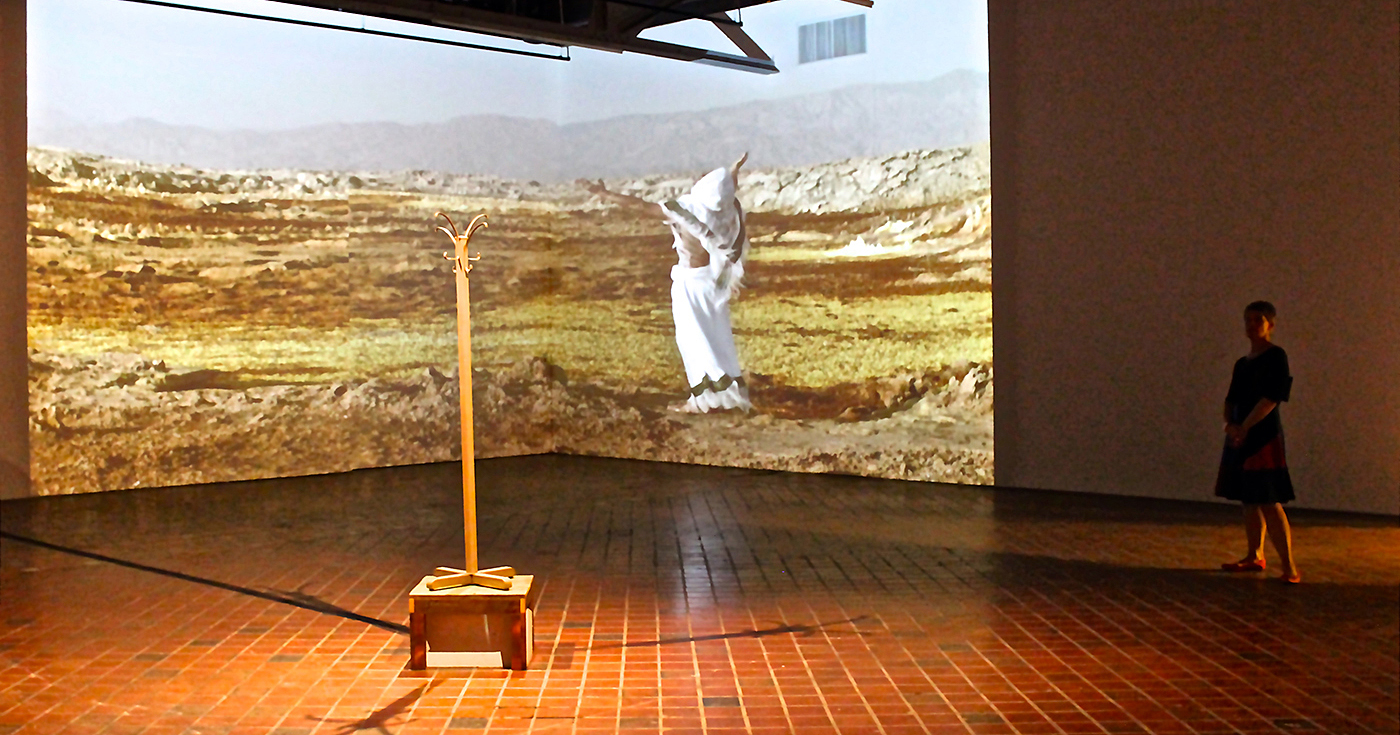

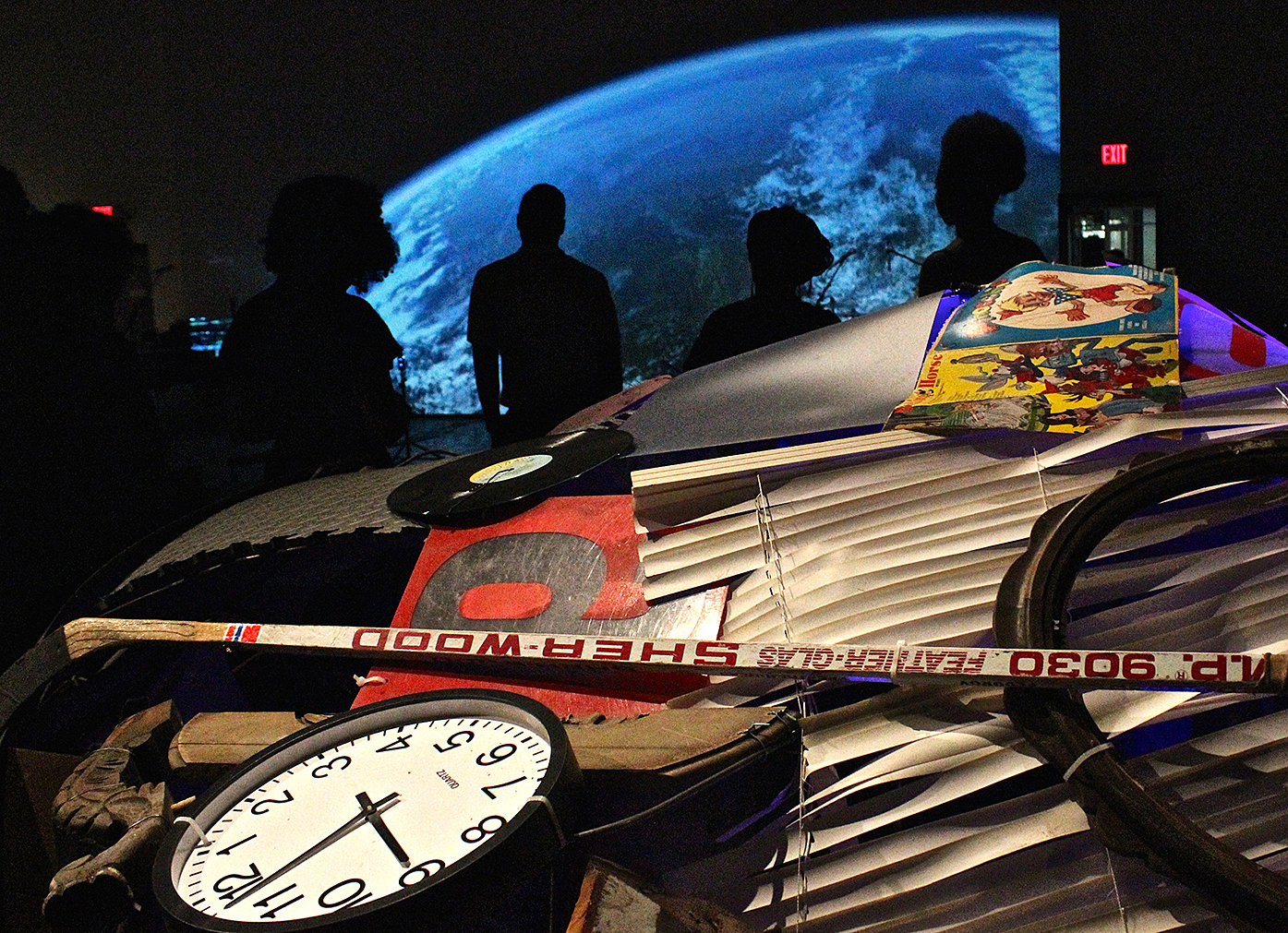

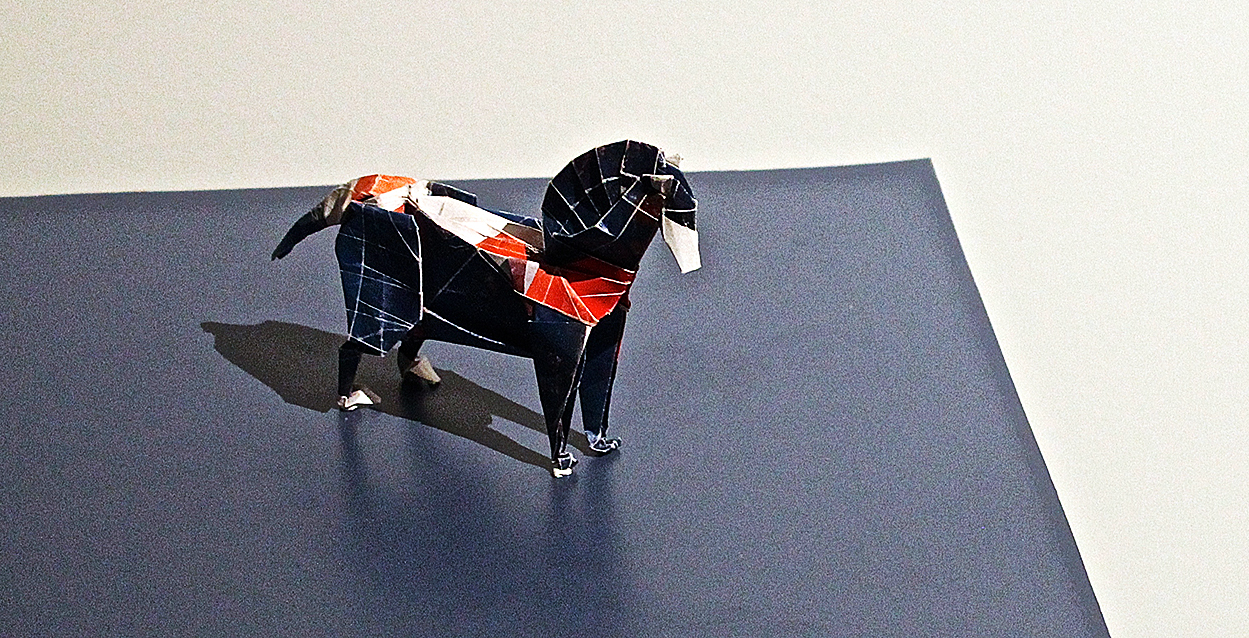

“I’m not focusing on one particular type of media in this conversation,” said Biggers, during the slide show and lecture portion of his artist talk at MOCAD, “because I consider myself to be a conceptual artist and an inter-media artist.” Indeed, the work within Subjective Cosmology runs the media gamut: kinetic inflatable sculpture in vinyl, multi-layer staged video art and footage collage, live musical performance, found object assemblage, fiber wall mosaic, and even a tiny, delicate origami-style paper horse. There is media-within-media; an object sculpture based on a large-scale industrial spool is displayed in one corner, but also appears in some of the video footage, being rolled around by figures wearing the same feature-obscuring masks donned by the members of Moon Medicin in live performance adjacent to the video collage (and subsequently displayed on a coat rack in the midst of the exhibition). Video clips projected on three walls of the exhibition alternately display process videos of the creation of a recent series of small bronze sculptures, formed by “ballistic sculpting” (aka being augmented by being shot through with bullets).

Sandord Biggers, From the Moon Medicin performance 2016

Biggers deals almost exclusively in “ethnographic objects,” picked up through his international travels and residencies. Just as he engages with myriad media, Biggers seems to create no boundaries for himself in terms of cultural source material, resulting in a final product that might be considered ethnographic collage. This practice recently drew some fire from critic Taylor Aldridge, with particular focus on a piece titled Laocoön—the original appeared at Art Basel Miami last December, and there is a scaled-up version of the same work currently on display at the MOCAD. The supine figure on display in the piece is instantly recognizable as the titular character of the cartoon show Fat Albert, and his labored posture, made kinetic by a cycle of slight inflation and deflation, signals a dying breath that triggers a host of loaded connotations. Most immediately, one thinks of the show’s creator, Bill Cosby, who has fallen from hallowed status in the wake of rape accusations—but the positioning and the association with breathing cannot help but conflate the figure on display with the victims of lethal and excessive force in a wave of high-profile conflicts with police officers around the country. The leveraging of this loaded imagery has spawned its own kind of art-world fetishization of black bodies—much as the horror of sexual violence against women has become almost banal in its pervasiveness as subject material for wildly popular TV shows like Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, or Criminal Minds.

Sanford Biggers, Moon Medicin costumes on display; according to Biggers they have now been retired and there will be new costumes at the next performance.

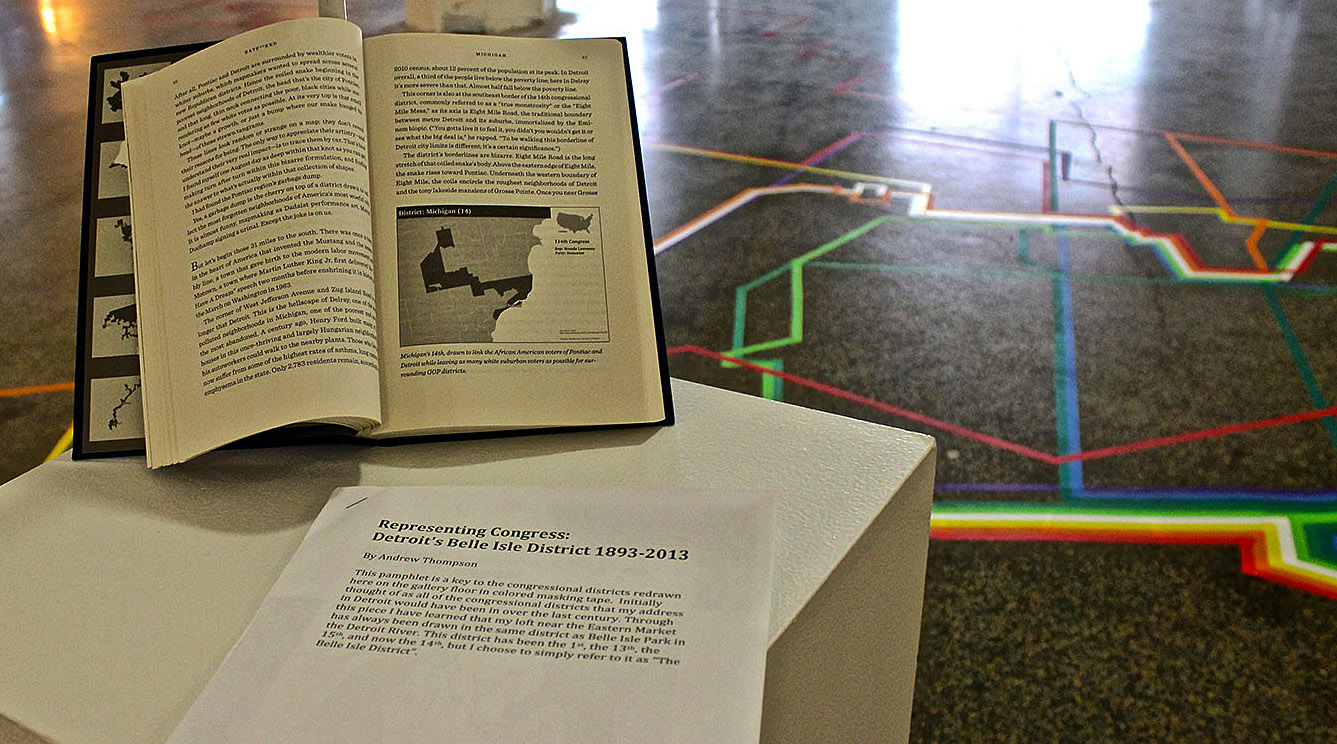

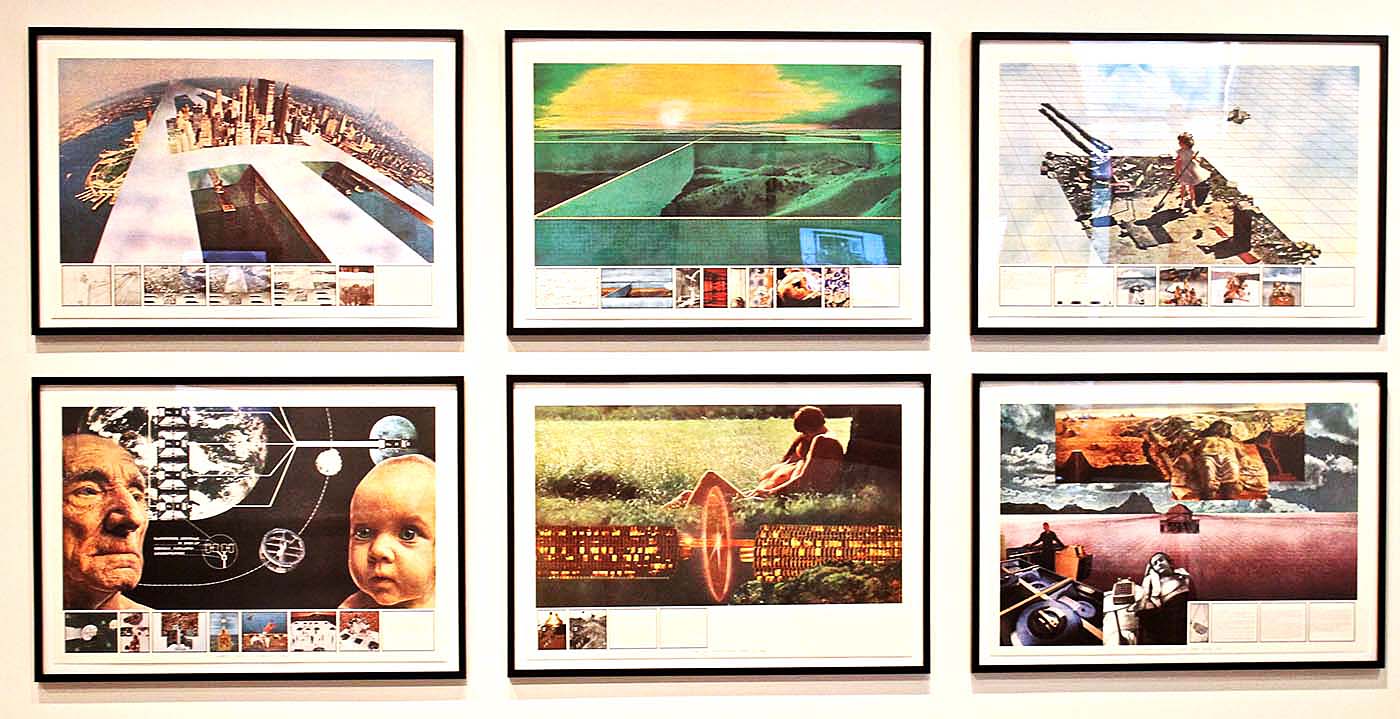

Certainly, Aldridge is entitled to her objections around the context and impulses at work in Laocoön, but it strikes me that the question raised by Biggers’ work is more one of appropriation on a broad level. Perhaps Biggers is trading in trauma associated with recent news events, but he deals equally in trauma associated with the slave trade—as with Lotus, an etched glass piece that mashes up renderings of the cargo hold on an 18th century slave vessel with the traditional Buddhist symbol for purity; as with Blossom, which brings the haunting subtext of the American jazz standard, “Strange Fruit,” to bear on the “Jena Six Incident,” involving an altercation between black and white students in Jena, Louisiana; and in Shuffle, Shake, Shatter, a three-part film/video suite on display at the MOCAD, which explores identity formation while abstractly retracing the North Atlantic Slave Trade route, from Europe to the Americas and finally Africa.

Sandford Biggers, Video projections (still view) 2016

“I was thinking about appropriation, and what does it mean to use these symbols,” said Biggers in his artist talk, referring specifically to a series of works that involved obscuring and embedding objects in plastic Buddha statues, such as B-Bodhisattava. “I realized…all bets were off. You can put anything you want to in this [clear-cast Buddha].” Cultural appropriation is a sticky subject, particularly when one is in the position to capitalize on the potential suffering or ideas of others, and Biggers work raises questions in terms of who is entitled to claim certain cultural cache—and potentially profit from it—and who is not. The most de facto stance is to draw racial boundaries with respect to certain cultural traditions, but the fact of the matter is, the bulk of Americans are descended from willing or unwilling transplants from other places, and one’s ability to claim any given heritage can be tenuous, depending on who you ask.

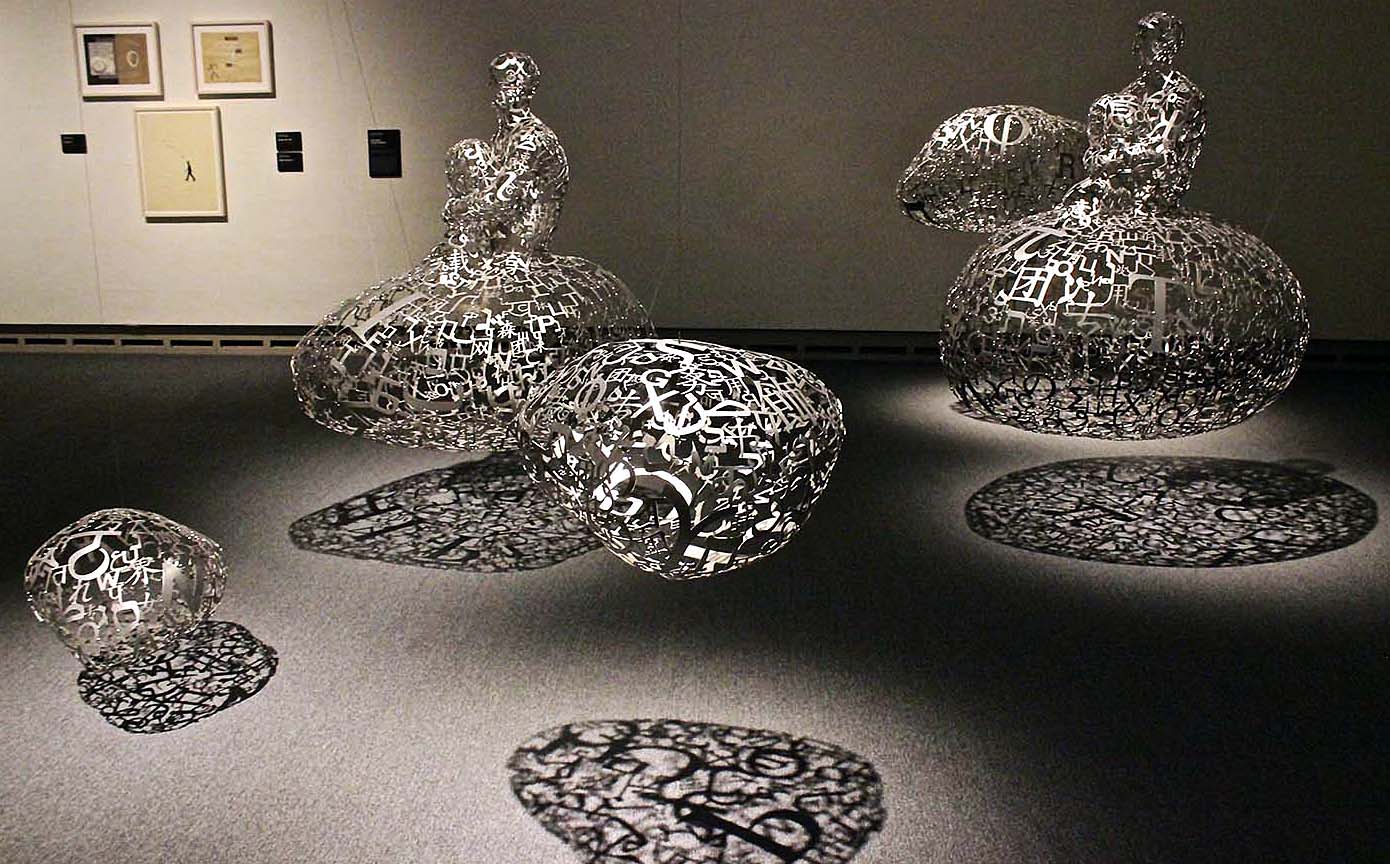

Sanford Biggers, Sleeping Giant (detail view) 2016

On some level, Biggers appears to be skimming the surface of so many different cultures that his work at the MOCAD merges into a kind of living collage—it feels unclear, at times, if the whirl of symbols and signifiers have actual meaning, or if we merely live in a society so densely programmed with media referencing other media that you can create a sense of meaning by the old Mortal Kombat strategy of simply mashing a lot of buttons at once. Moon Medicin kicked off their MOCAD performance with a cover of “Fly Like an Eagle,” wearing cartoonish masks, in front of video clips from Cool World and Who Framed Roger Rabbit—both movies that juxtaposed animated and “real” world imagery. The meta-ness of the moment was perhaps enough to feel as though something was going on, but what, exactly, is left pretty widely open to interpretation.

Sanford Biggers, Seen, 2016

In fact, Laocoön references a statue, which references a piece of somewhat ambiguous Greek mythology. The eponymous subject of the story committed a transgression—in some versions he drew ire from Athena for attempting to reveal the military gambit of the Trojan Horse, in others he disrespected a temple of Poseidon—and was punished with the death of his sons. That Biggers has chosen to double-down on the presentation of this contentious work (literally tripling the height of the piece in this iteration) underscores a double-bind that is as ambiguous as the variations on the tale: Laocoön was either punished for doing wrong, or for being right. In his grasp-and-mash-up, is Biggers doing wrong? Is he right, and all bets are off, when it comes to cultural appropriation? Does this practice enhance understanding and bridge cultural divide, or does it wedge a dangerous foot in the door for people to perpetuate sensationalist imagery and culture-grabbing for their own gain? When does collage as a form generate richness in meaning, and when does it become mere sensory overload?

When dealing in cultural imagery this heavily loaded, these are the questions every responsible viewer must ask and decide for themselves—and Subjective Cosmology is perhaps more fertile ground than most to meditate upon these thorny considerations. As the title would suggest, what you read in Biggers’ cosmos is entirely up to you.