The actress Lillian Gish (1893-1993) was called the “First Lady of American Cinema,” as the earliest prominent female film star from 1912 to the 1920s. In screen performances that defined the role of women in silent cinema, Gish was the image of the archetypal suffering heroine that gained strength through trauma. It was the stuff of pure melodrama.

“Night Hunter”, Installation view at K.OSS Contemporary Art Gallery, All images: K.OSS Contemporary Art Gallery

Artist and filmmaker Stacey Steers resurrects Gish in the animated short film Night Hunter (2011), which was created from 4,000 collages on paper and shot on 35mm film. It can currently be viewed as the centerpiece of the exhibition “Night Hunter” at the K.OSS Contemporary Art Gallery, alongside a selection of the collages used in its making and a reconfiguration of excerpted scenes within two sculptural installations. Steers work in “Night Hunter” evokes the literature of dark fairy tales, gothic horror and doomed Victorian romance as shot through with the intuitive approach to narrative construction found in Surrealist art and cinema. Rich in seemingly-incongruous symbolism, the film and its component parts untether and collect the raw material of the subconscious within a psychologically complex space that turns the psyche inside out. Although Steers evokes the imagery of the past, she also works to actively deconstruct and subvert the meaning of that imagery.

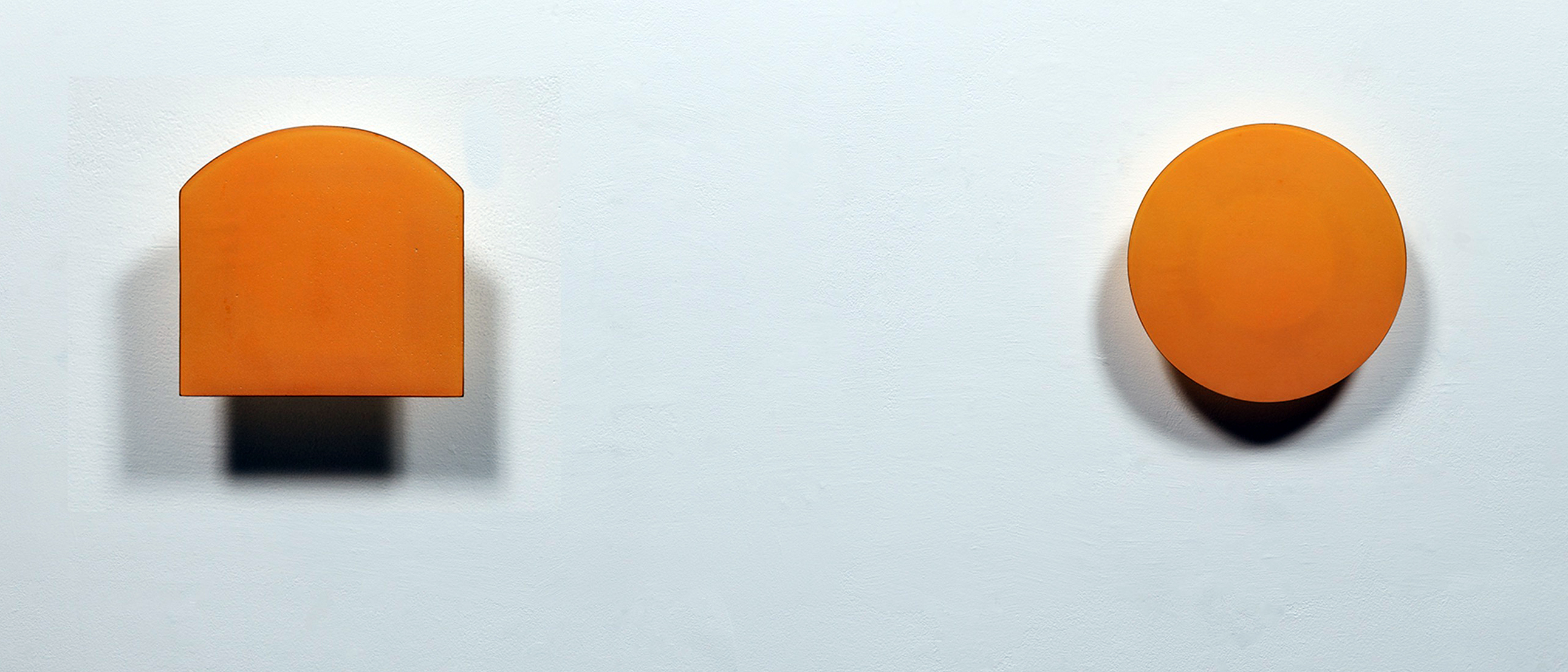

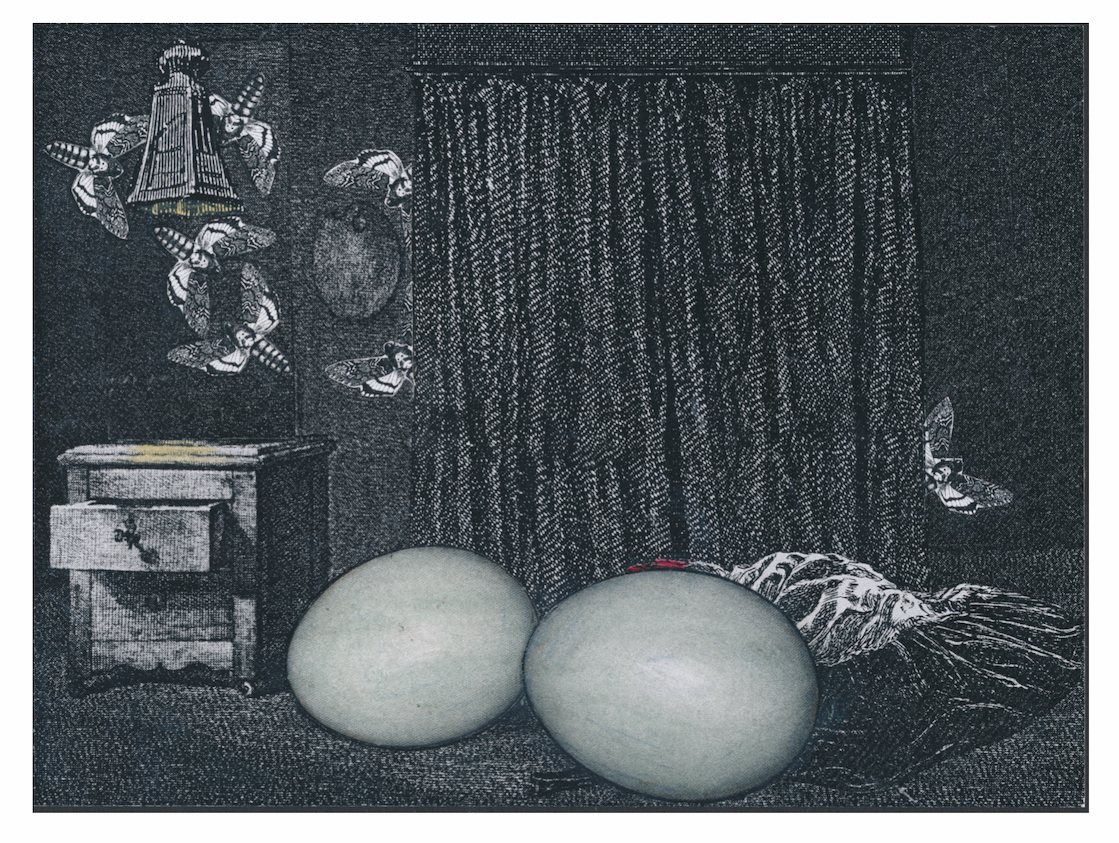

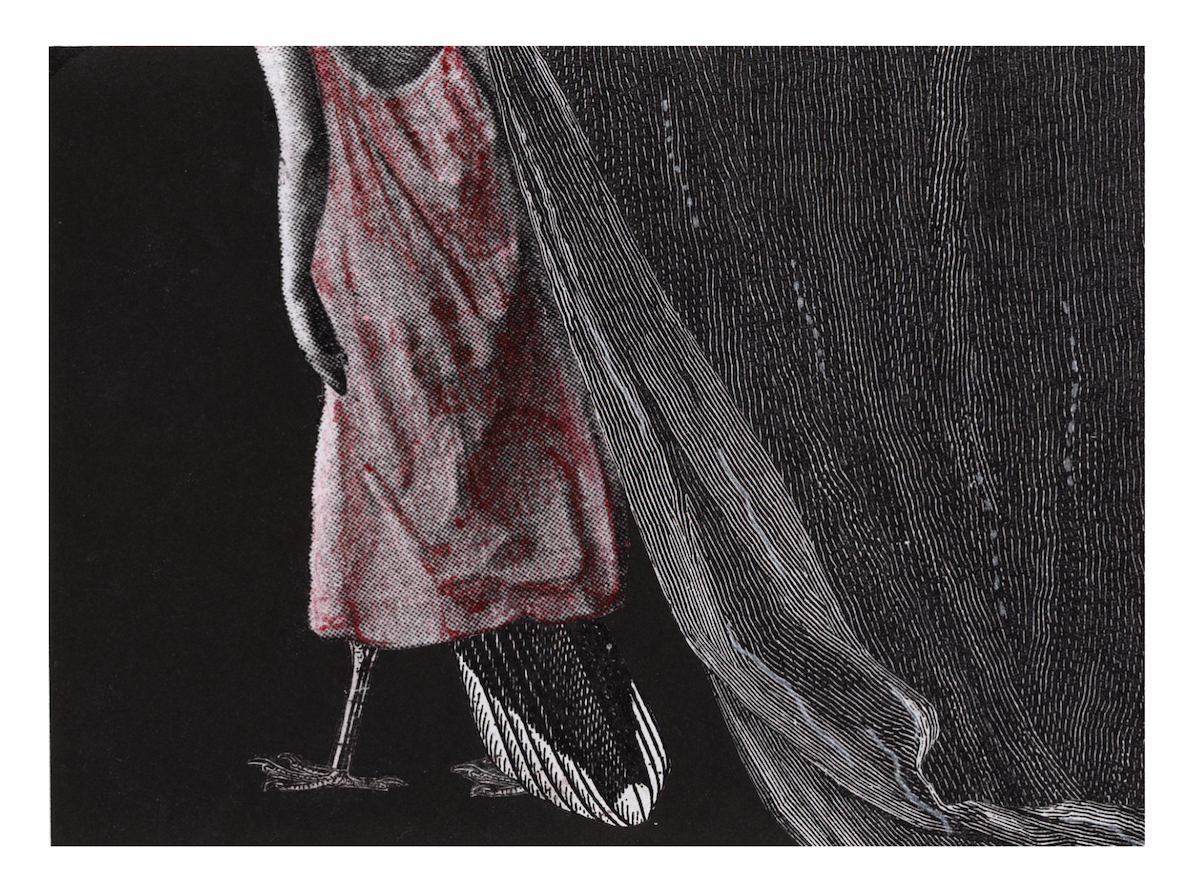

Stacey Steers: Single Collage, 22 x 18 x 1 inches, 2011

The exhibition “Night Hunter” calls forth many slivers of the ornately imagined past, beginning with The Night of the Hunter (1955), directed by Charles Laughton from a screenplay by James Agee. Set in West Virginia in the 1930s, that film stars Robert Mitchum as the misogynistic serial killer and self-appointed preacher Reverend Harry Powell, who attempts to hunt and kill a boy and a girl escaping his clutches along the Ohio River. He is a snake who enters the garden. There are numerous elements in the “Night Hunter” exhibition that converse with Laughton’s film, which is a highly stylized, expressionistic work photographed with the distortions and excessive play of shadows that haunt the dreams of children. The sets of the film appear as dimly lit dollhouses in the void, swallowed up by an ever present gloaming. Its action unfolds in an unreality— a studio lot rendition of night teeming with reminders of the natural, bestial world on the verge of devouring innocence. Lillian Gish even appears in The Night of the Hunter, as an older, wiser, gun-toting woman who keeps the Reverend at bay.

Stacey Steers: Single Collage, 22 x 18 x 1 inches, 2011

Steers’ film Night Hunter has as its setting, a house in the dark woods, where a youthful Lillian Gish, reanimated in footage excised from silent dramas such as Broken Blossoms (1919), True Heart Susie (1919) and Way Down East (1920), all directed by D.W. Griffith, and The Wind (1928) directed by Victor Sjösström. In this last film, the final silent performance of Gish, she plays a heroine who suffers at the hands of male brutality until she commits murder. Steer’s narrative thoroughly resonates with the history of Gish’s screen characters. In her Surrealist fairy tale, we are presented with the trappings of a haunted house rife with phantasmal stirrings. At the start, Gish, alone in the house, is sewing and cooking. Lace curtains part to reveal the starry night outside. Pots boil over. Death‘s-head hawkmoths are flitting about. The moodily detailed score by composer Larry Polansky establishes a space that is at once airy and yet also oppressive, with a mixture of sounds that conjure restless spirits within walls on the verge of talking. This is a scene of the domestic mundane laced with gothic horror. There is a raven clutching a writhing green earthworm within its beak. Oversized eggs bleed, the weeds penetrate up through the floorboards, a storm of moths flutter from the open drawer of a desk. Our heroine is writing a letter: “Strange things happening, mother.”

Stacey Steers: Single Collage, 22 x 18 x 1 inches, 2011

And soon, there is a snake: the intrusion of the phallic in the form of a venomous Copperhead. It is here that Steers relies upon the silent film archetype of the heroine in peril, as the snake threatens and the environment grows increasingly stifled. But there is a reversal, as one form of nature vies for dominance over another. In an echo of Camille Paglia’s feminist reading of Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds (1963), the force of feminine nature emerges as an act of reclamation in the face of the domestic as Lillian Gish flees the house to seek refuge within the dark of the surrounding forest. Night Hunter ends on a note of release.

The film harkens back to Surrealist works in its construction. The resuscitation of silent film footage incorporated into a new narrative recalls the film work of assemblage artist Joseph Cornell (1903-1972), whose experimental “found film” Rose Hobart (1936) was constructed from shuffled and reworked scenes from the 1931 “B” movie East of Borneo. Cornell would fixate upon repeated gestures and expressions of the actress Rose Hobart throughout the film in a manner that traps the actress under the male gaze. Alternately, Steers liberates the image of Gish as an active participant in her narrative.

Stacey Steers: Single Collage, 22 x 18 x 1 inches, 2011

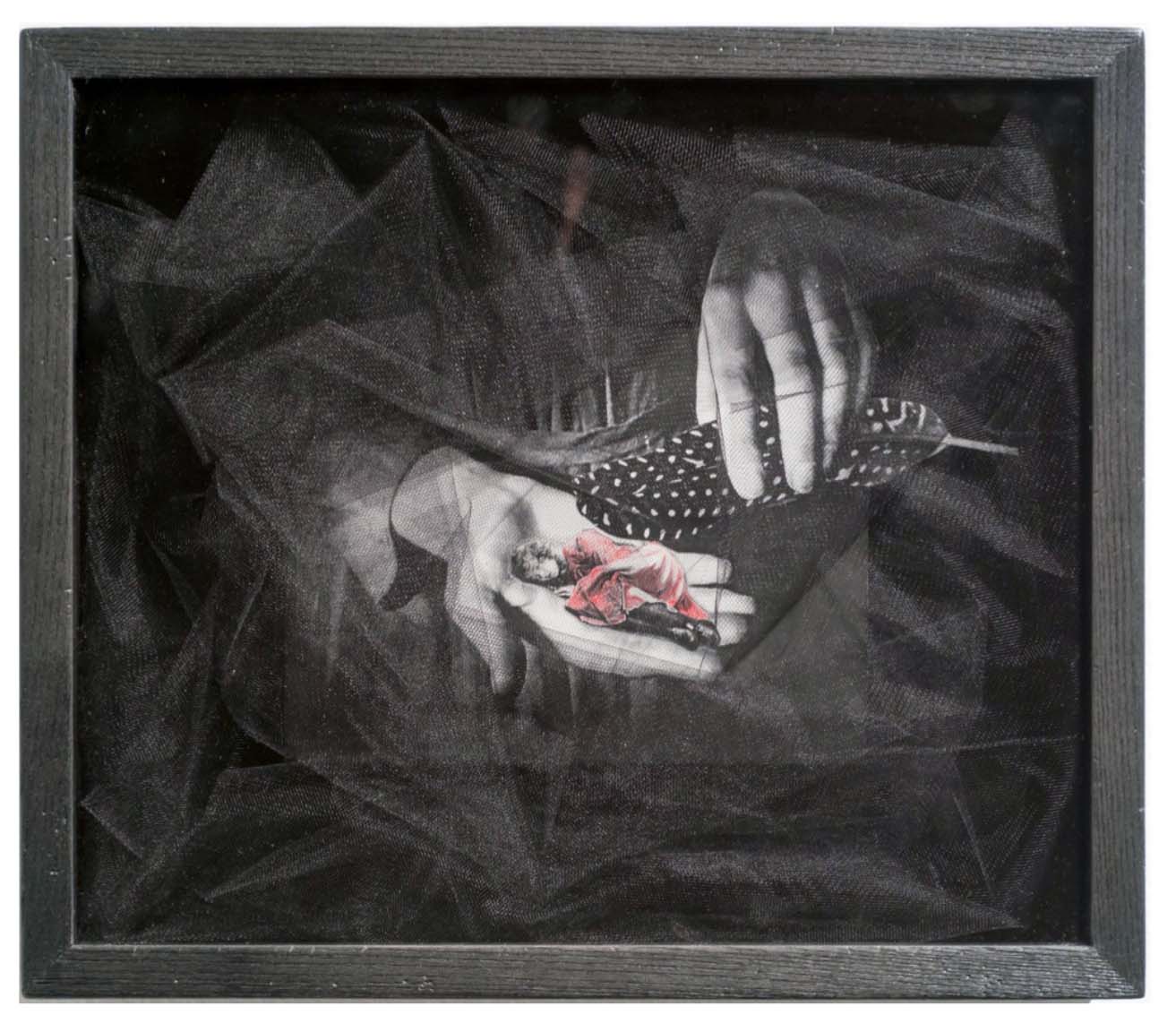

Steer’s Night Hunteralso gestures toward Max Ernst’s 1934 collage novel/comic book Une Semaine de Bonté (A Week of Kindness), in which the Surrealist artist set about cutting up and reorganizing a plethora of print images culled from Victorian novels, encyclopedias and natural science journals. For Ernst and many other Surrealists, this intuitive act of arriving at new meanings through the intuitive suturing of inert images rescued from the cultural dustbin was an act of liberating that which had been previously repressed in source material. Steer’s work is similarly concerned with the use of collage and montage as an act of deconstruction and reconstitution. The exhibition itself is conceived to reflect this process as the viewing of the complete 16-minute film of Night Hunter is supplemented by twenty of the collages used in its production. But rather than ossifying the experience of the film, the collages enlarge upon the space of the narrative. The film itself is manufactured from material that is fragmented and then reassembled. To then take the film and break it down into moments framed and placed behind glass, sometimes in shadow boxes with mixed media adornments, is to create auxiliary incidents that reshuffle the memory of what has just been seen.

When viewing these individual, static collage works, plucked from the moving continuum, one can appreciate the skill with which Steers approaches the visual texture of her film. When the celluloid images advance, there is that poetic, jostling motion of handmade animation, the meaningful delays and lapses that reinforce the simultaneous decay and reanimation of time. In a frozen state, each image yields the detail of their source material: the engraved, etched, and half-toned language of print alongside the grain of silent film stock with hand-colored additions.

Stacey Steers: Shadow Box, mixed media, 11 x 13 x 3 inches, 2011

The very notion of reshuffling time, abandoning the linearity of the narrative, allows for a different sort of immersion in the world Steers has created. Here too, one can glance back at a Surrealist predecessor: Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s silent film experiment in non-linear cinematic narration Un Chien Andalou(An Andalousian Dog) (1927) with its shocking eyeball sliced open by a straight razor serving as a powerful symbol for the Surrealist intent in slicing open the image. But whereas Buñuel and Dalí leaned heavily on Freudian theory and the repeated victimization of their heroine in the film, Steers empowers her heroine. And that she does so after swallowing the same death’s-head hawkmoth glimpsed in Un Chien Andalou, should not be overlooked.

Stacey Steers: Night Hunter House, wood, Nixplay screens and mixed media, 60 x 36 x 36 inches, 2011

Included in the exhibition are two sculptures, Night Hunter House and Cottage that go further to represent the central film project in an alternative light. The house is a Victorian model measuring 60 x 36 x 36 inches, painted entirely in matte black, with windows that reward the viewer access to the interiors of ten rooms, each with a small video screen playing loops of selected scenes from the film, each with furnishings that echo the animated narrative. The dim lighting of the rooms and the scale of each video loop, fortifies the intimate domestic space viewed on the larger screen. It also reshuffles the narrative once again, as the observer glances from window to window catching a fragment here and there, the gaze drifting to the miniature objects found within. We make ourselves small and burrow back into this house, whose very architecture is the symbol for so many stories relating to the ghostly, the horrific and the romantic.

Stacey Steers: Cottage, wood, Nixplay screens and mixed media, 19 x 13 x 11 inches, 2011

With Cottage, a 19 x 13 x 11 inch construction similarly painted matte black and presenting a single screen video loop within, and with “House,” Steers revels in the relationship between narrative and architecture. In these miniature, darkened spaces, she has fashioned pitch black galleries within the larger white cube. They are temporal dream spaces for us to project ourselves into, collecting her flickering images to take back into the light of day as fragmented memories that will later rejoin into an altogether different narrative upon reflection.

The exhibition “Night Hunter” by Stacey Steers is on view at K.OSS Contemporary Art from May 24th through July 13th, 2019.