Installation, We Used To Gather, Library Street Collective, 8.2020

The walls of Detroit’s Library Street Collective are lined floor to ceiling with vibrant canvases that match the bright, sunny days of this hot Detroit summer. The gallery’s first opening since the widespread closures following the COVID-19 pandemic, We Used to Gather ambitiously responds to communal anxieties with a series of figurative works by 26 different artists. As we begin to tiptoe wearily out of social isolation, many of us are reflecting on what we learned both about ourselves and our relationships with our communities over the past few months. The show reminds us that reflections of ourselves are everywhere we look and often, we struggle to make sense of what we see. The title itself recalls a time when we were able to gather freely, only here, the presence of others is supplanted by two-dimensional representations.

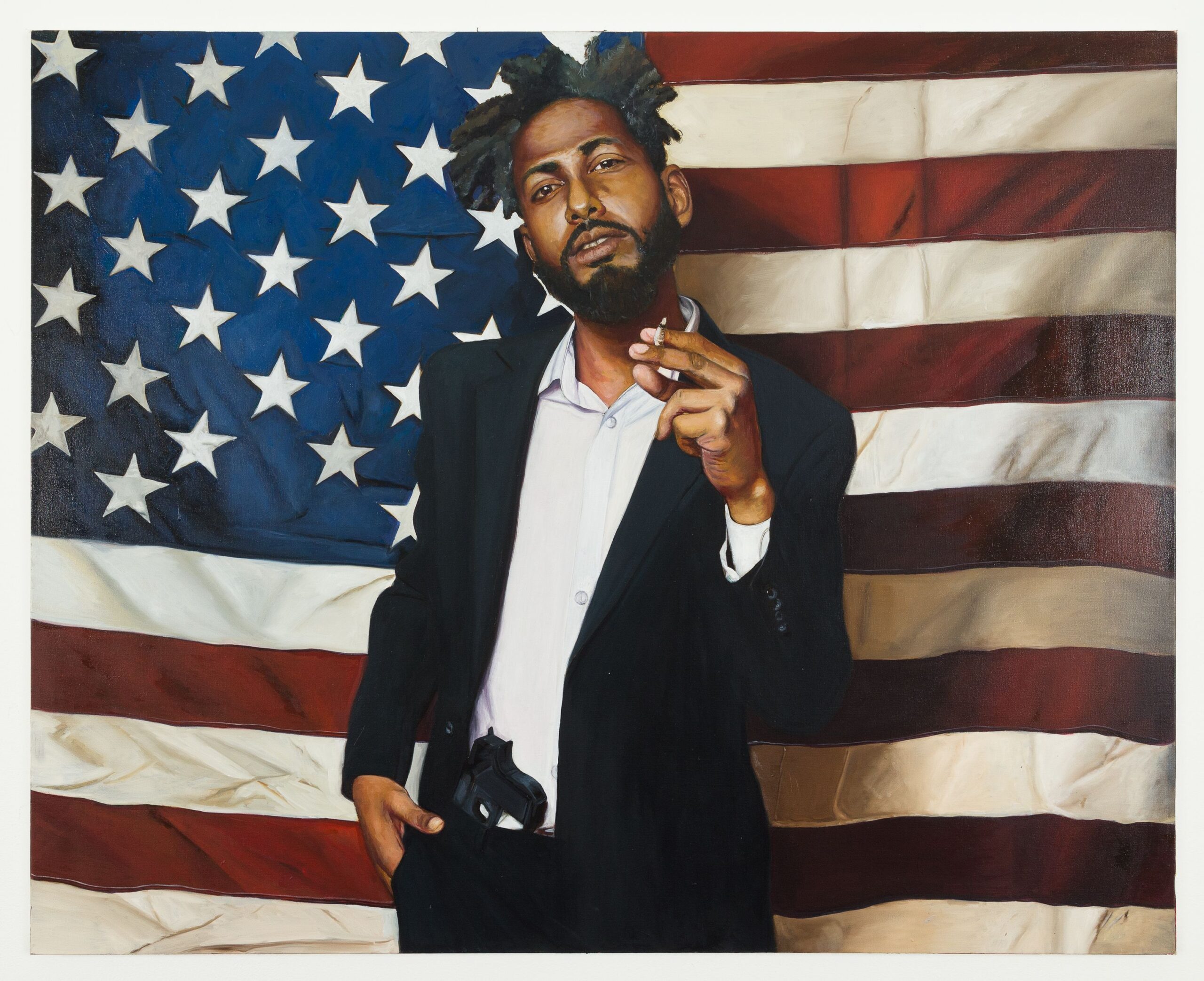

Tylonn J. Sawyer, American Gangsta: Uncle Sam, 2018 Oil on canvas 48 x 60 in. (121.92 x 152.4 cm)

At the very entrance of the gallery, the eye is immediately drawn to Tylonn J. Sawyer’s American Gangsta: Uncle Sam, 2018. Sawyer’s fine technical skill and command of his medium shine through in this life-sized depiction of a Black man sporting a clean suit and touting a cigarette in front of the American flag. With a gun tucked in his belt line, he peers critically out of the canvas. His dubious expression begs the question: who exists to protect and serve America? And likewise, who does America exist to protect and serve?

Conrad Egyir, Sydney King, 2020 Oil with mixed media on panel 48 x 48 in. (121.92 x 121.92 cm)

Conrad Egyir, JustTina, 2020 Oil with mixed media on pane, 48 x 48 in. (121.92 x 121.92 cm)

Conrad Egyir touches on similar themes in the two works he has featured in the show. In Sydney King and JustTina, his subjects are framed by another hallmark of national institutionalism: the postage stamp. Both women gaze outwards with their right hands laid gently over their hearts. Ghanan-born Egyir is interested in how African identity is perceived as it travels across the diaspora. The postage stamp is quite literally a vehicle for the transportation of words and ideas. It also serves as a sort of tribute to those prominent figures who we, as a society, have chosen to honor. In these two works, Egyir chooses to honor Black women, whose lived experiences and contributions are far too often overlooked in daily life.

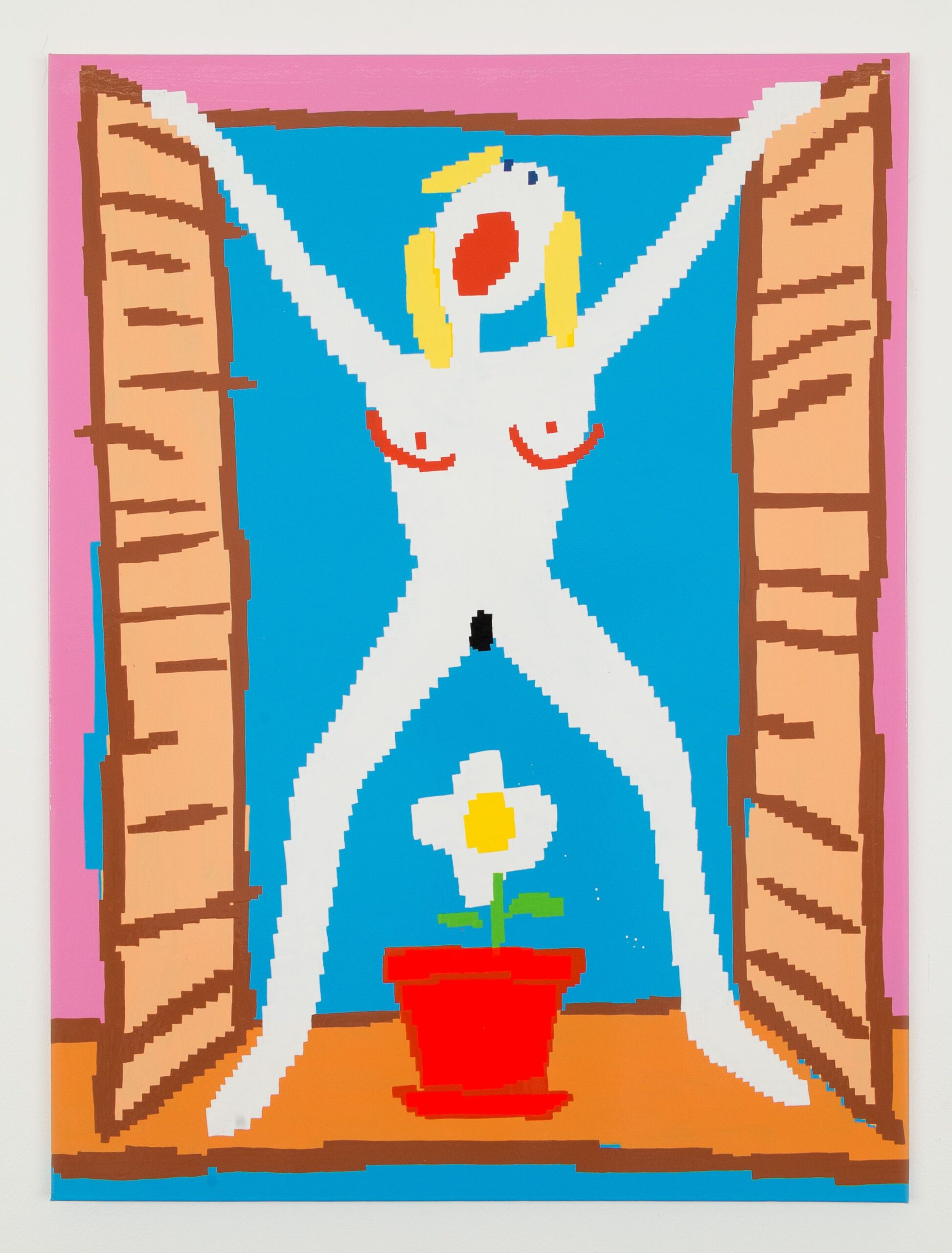

Maja Djordjevic, Be here and be loud, 2020 Oil and enamel on canvas 48 x 36 in. (121.92 x 91.44 cm)

Maja Djordjevic, Waiting and hoping, 2020 Oil and enamel on canvas 48 x 36 in. (121.92 x 91.44 cm)

A little further down the salon-style lineup of paintings hangs a work by Serbian artist Maja Djordjevic. The artist has two pieces featured in the show, both of which depict a pixelated nude female figure in dramatic posture. With her stiff limbs and mouth fixed open, she bears semblance to an inflatable sex doll. Though painted entirely by hand without tape or stencils, the digitized style of Djordjevic’s work alludes to the virtual realities many of us live via the internet, especially over these past few months when contact with the outside world has been so limited. To whom do we turn for comfort during these trying times? More often than not, it’s the women in our lives, be they real or digitally imagined, who play the role of caregiver.

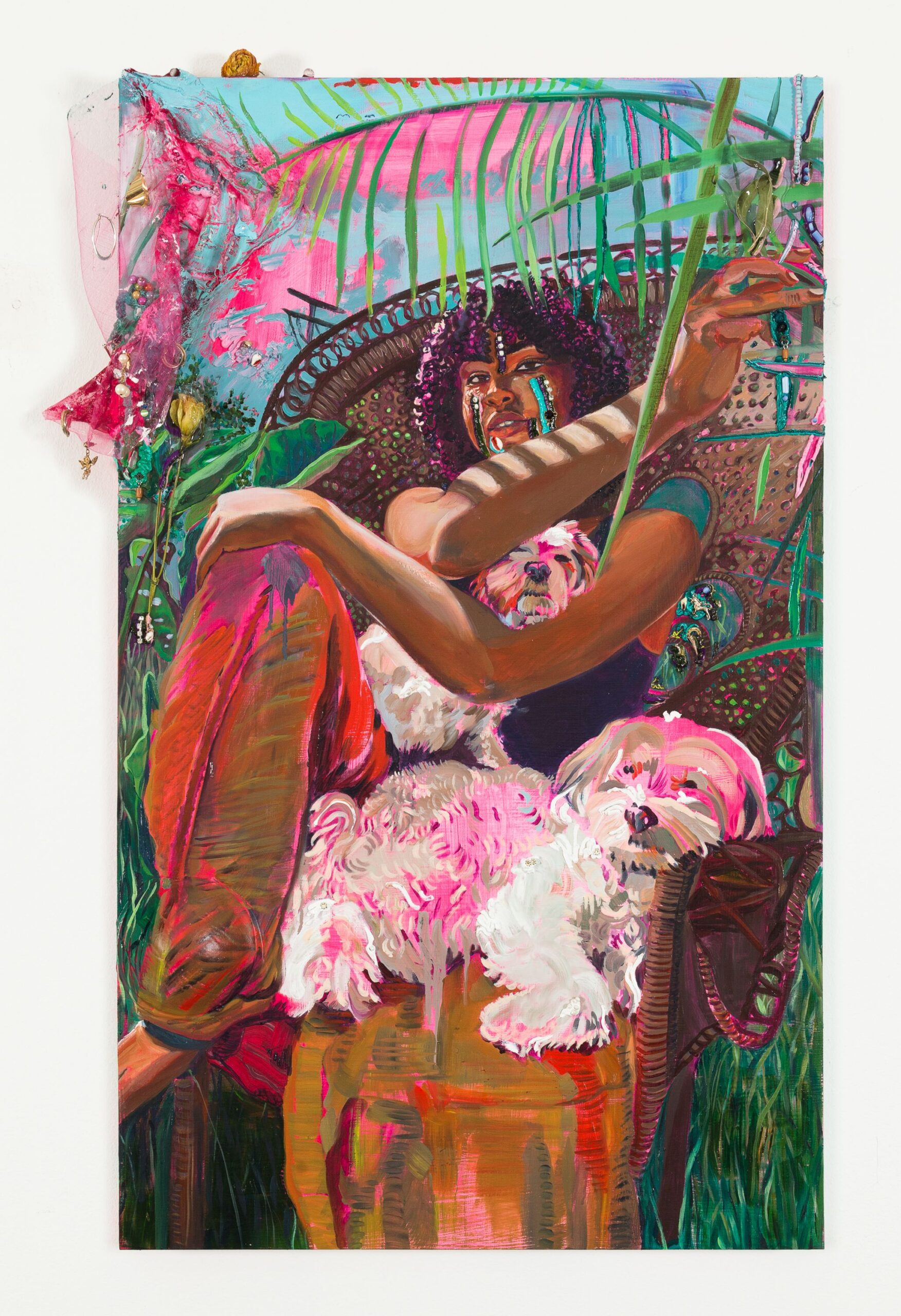

Gisela McDaniel, Do Right, 2020 Oil on canvas, found object, resin, flower, sound on USB, 40 x 20 in. (101.6 x 50.8 cm)

An ode to the feminine is also made in Gisela McDaniel’s Do Right. McDaniel creates visual realms where victims of sexual abuse can seek refuge from their trauma. In Do Right, a woman envelops herself gracefully in her own criss-crossed arms. Intertwined with her are two small white dogs. Bright colors, vibrant foliage, and three-dimensional trinkets fixed to the surface of the canvas all serve to delineate a personal fortress where this woman reigns free. Stories, especially as they are told and personally reclaimed by women, are at the heart of McDaniel’s work.

Jammie Holmes, Untitled, 2020 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 44 in. (152.4 x 111.76 cm)

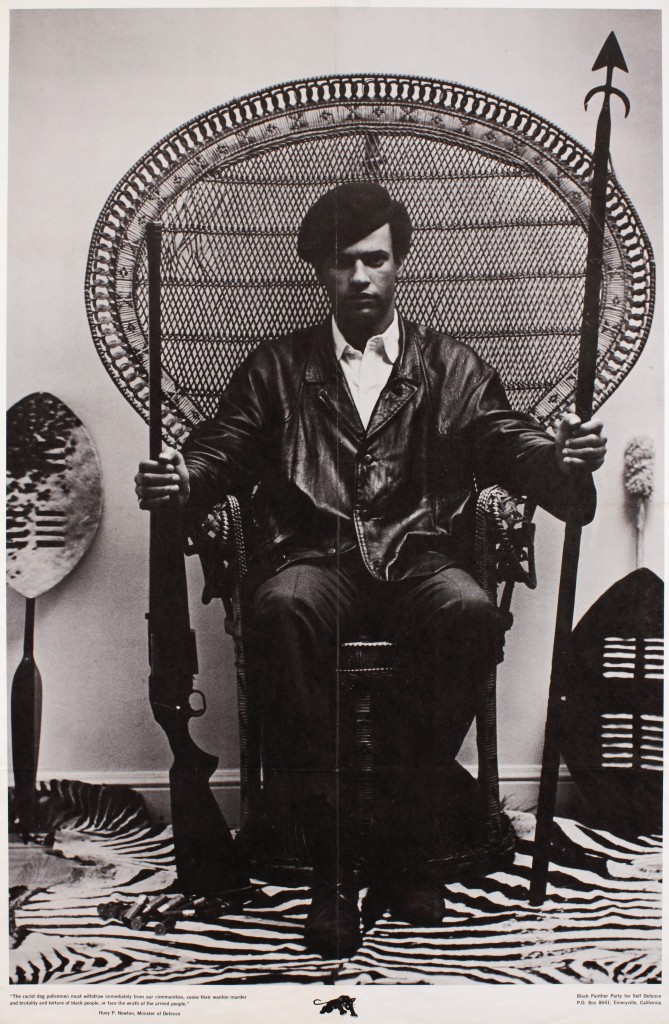

The show also features two works by Louisiana-native Jammie Holmes. His untitled work depicts a young man sitting, facing squarely forward, on a wicker Peacock Chair. The ornate chair was popularized in the twentieth century by countless celebrities and public figures who often posed sitting in the chair for portraits, album covers, and publicity stunts. One famous Peacock Chair portrait is that of Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party. Here, the subject is poised in a commanding position of authority, not unlike that of Newton’s in his respective portrait. It is not difficult to imagine that Holmes might have intended to invoke the radical notions of the Black Panther Party during a time in the United States when police brutality against Black people is at the forefront of national attention.

Photography attributed to Blair Stapp, Composition by Eldridge Cleaver, Huey Newton seated in wicker chair, 1967. Lithograph on paper; Collection of Merrill C. Berman

Marcus Brutus, Annie, 2020 Acrylic on canvas 30 x 24 in. (76.2 x 60.96 cm)

Along the same lines, Marcus Brutus has four intimate portraits featured in the show. Each of them center in on a Black male figure set against bright yet minimal backgrounds. Annie is calm and stoic in its presentation of a young man gazing tiredly out of the canvas. His downtrodden expression and timeless dress are enlivened by the brilliant lime-green backdrop just behind him. Traces of bright green glint off of his skin. Brutus celebrates the ordinary with his reverent portraits of familiar faces.

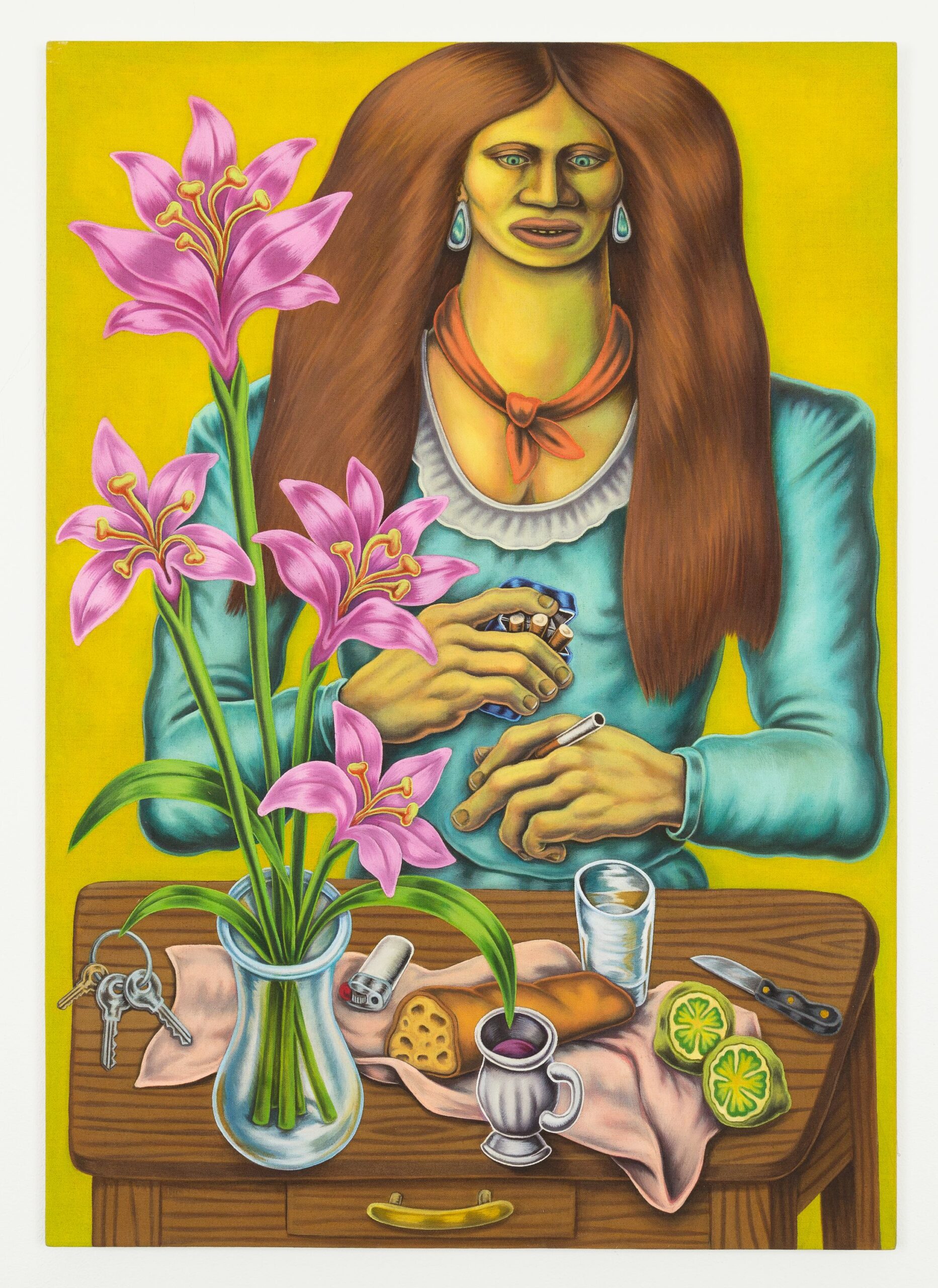

Pedro Pedro, Figure Fumbling for a Cigarette, 2019 Acrylic and textile paint on linen 49 x 34 in. (124.46 x 86.36 cm)

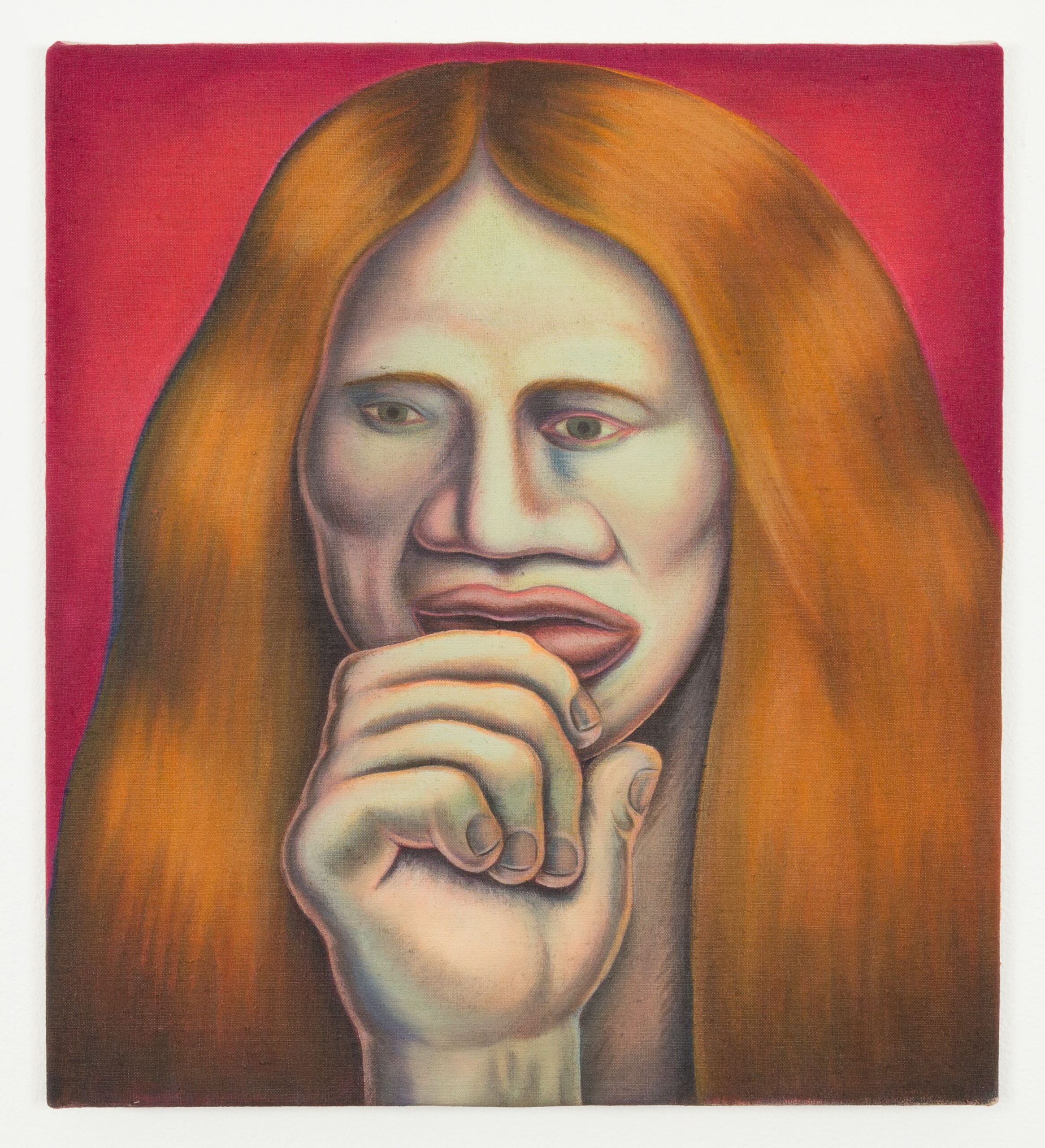

Pedro Pedro, Portrait of Kaitlin Concerned, 2019 Acrylic and textile paint on linen 19 x 16 in. (48.26 x 40.64 cm)

In fitting contrast, LA-based Pedro Pedro offers two portraits of female figures. The features of each woman are exaggerated to the point of comedic effect, yet each composition feels wholly balanced. The warm hues and richly blended colors pay service to the expressions of the women, each of which appear to be frozen in a moment of contemplation. The variation of style and concept in We Used to Gather might at first overwhelm, but ultimately succeeds in capturing the feelings of chaos and uncertainty most of us are experiencing in these trying times.

All works mentioned above as well as many others are available to view at Library Street Collective through September 18, 2020. The gallery is open Wednesday through Saturday, 12-6PM. A virtual tour of the exhibition is also available on the Library Street Collective website. 10% of the proceeds on any works sold from We Used to Gather will be donated to the Metro Detroit COVID-19 ACE Fund.

WE USED TO GATHER

Library Street Collective, July 18 – September 18, 2020 – 1260 Library Street, Detroit, MI 48226