Ruben Toledo, “Broomstick Librarian Shirtwaist Dresses,” 2008, Designed by Isabel Toledo, Painted by Ruben Toledo, image by DIA – William Palmer.

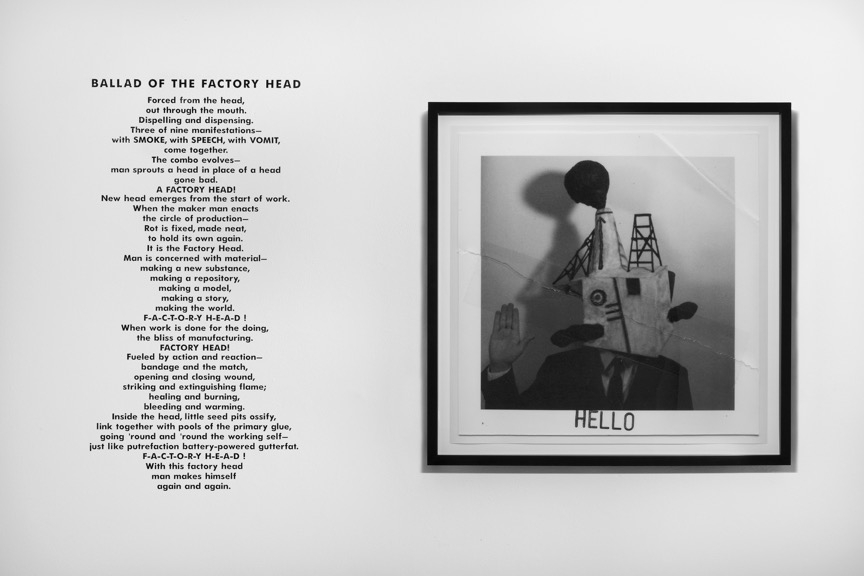

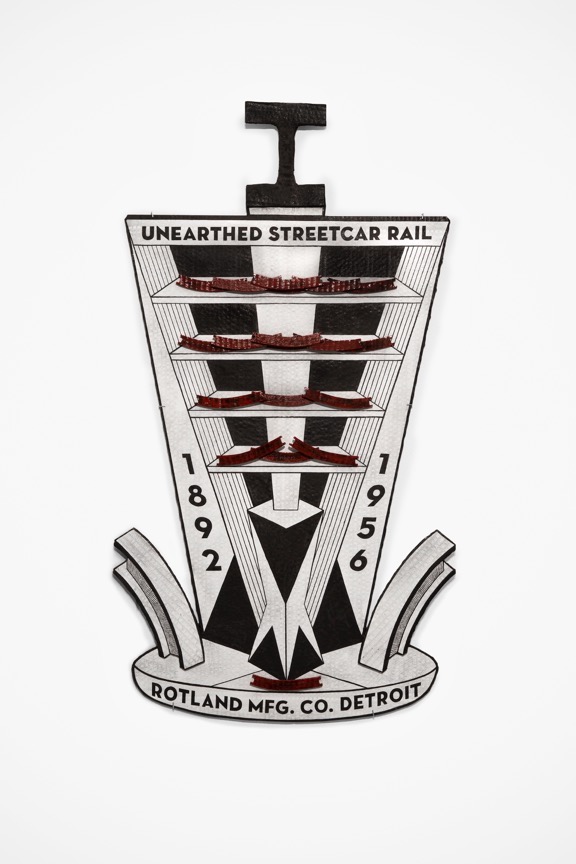

We normally think of industry as the machinery of the production for making a particular thing, like the steel industry, or, especially in Detroit, the auto industry, but entering the current exhibition, “A Labor of Love,” at the Detroit Institute of Arts, we are greeted by a magnificent image of twisted swirls of colors and pleats of seven dresses. This very energetic image was composed and painted by Ruben Toledo of his wife, Isabel Toledo’s dress designs for Anne Klein, one of the leaders in the Fashion Industry. It’s not a huge leap of the imagination to go from car design, with its annual turnover and retooling for the latest, sexiest, avatars of human desire, to the fashion industry and its latest adjustments of hem and neckline and introduction of the latest color to elaborate on the human body. That’s just what this famous New York husband and wife team of artist and designer did in “Labor of Love,” their investigative interventions in the encyclopedic collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Ruben and Isabel Toledo, “The Choreography of Labor,” 2018 Remaining images by DIA Eric Wheeler

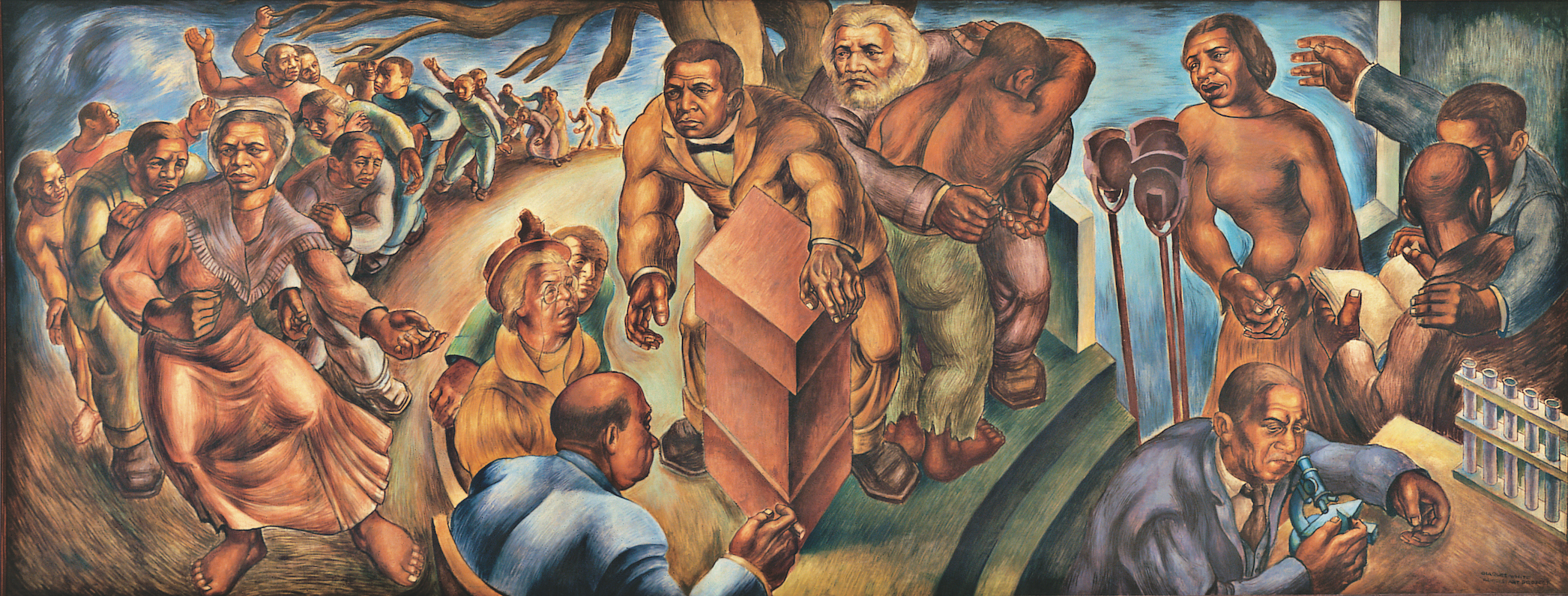

Situated in the DIA’s Special Exhibitions galleries, the main thrust of their installation is an exploration of Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry Murals,” the heart and soul of the museum and, art lovers might say, Detroit itself. In her exploration of the collection, Isabel Toledo saw the connection in Rivera’s fresco murals between the fashion and auto industry immediately and brought them together in a large collage (Image #2) that depicts a flowing dance of her dress designs across silkscreened representation of Rivera’s painting of the factory with workers depicted engaged in car production. The darkened gallery, filled with sculpted manikins wearing formal gowns of various cultural origin, suggests a grand promenade celebrating immigration and integration of world cultures to Detroit.

Installation image of Special Exhibitions Gallery with Isabel Toledo’s first sewing machine in foreground.

There is a haunting tableau composed of Isabel Toledo’s first sewing machine wrapped in black taffeta, with ghostly gowns floating in the air above, with a quote on the wall from Isabel that offers the idea of the fashion industry and (by proximity) the auto industry, as a metaphor for the generational influence of migration and change, of death and rebirth: “The combination of ideas, time and imagination can all be triggered by fashion and how people dress, undress, expose, or cover their bodies, fashion offers the perpetual next—the never ending now, the reinvention of inventions.” It is a twist on Darwinian Evolution that goes back to LeCorbusier’s use of it to explain the evolution of design. (Incidentally Isabel’s sewing machine, in looking like a little animal, echoes Rivera’s drawing of an V-8 engine block that looks like a dog).

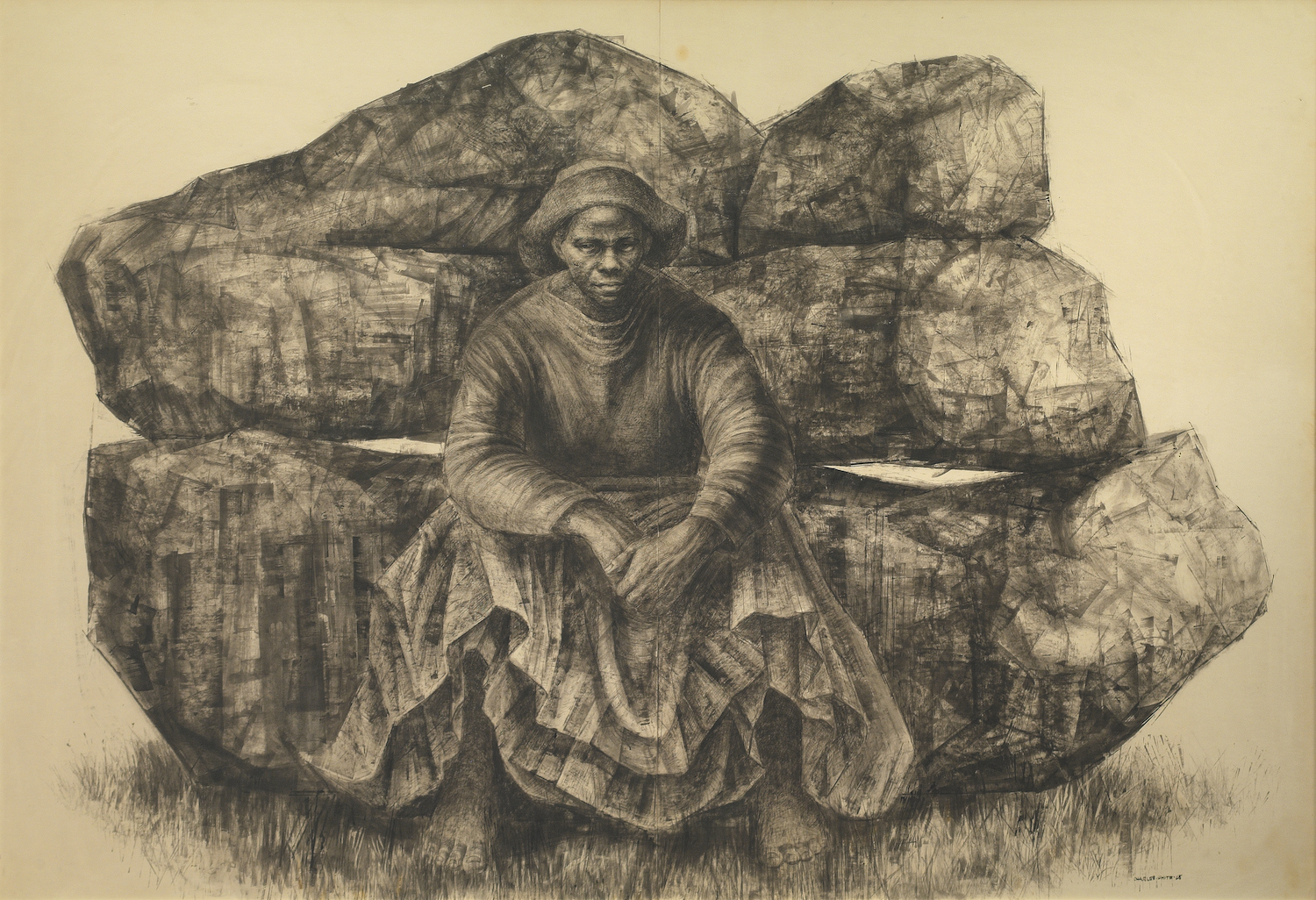

Diego Rivera drawing from DIA Collection

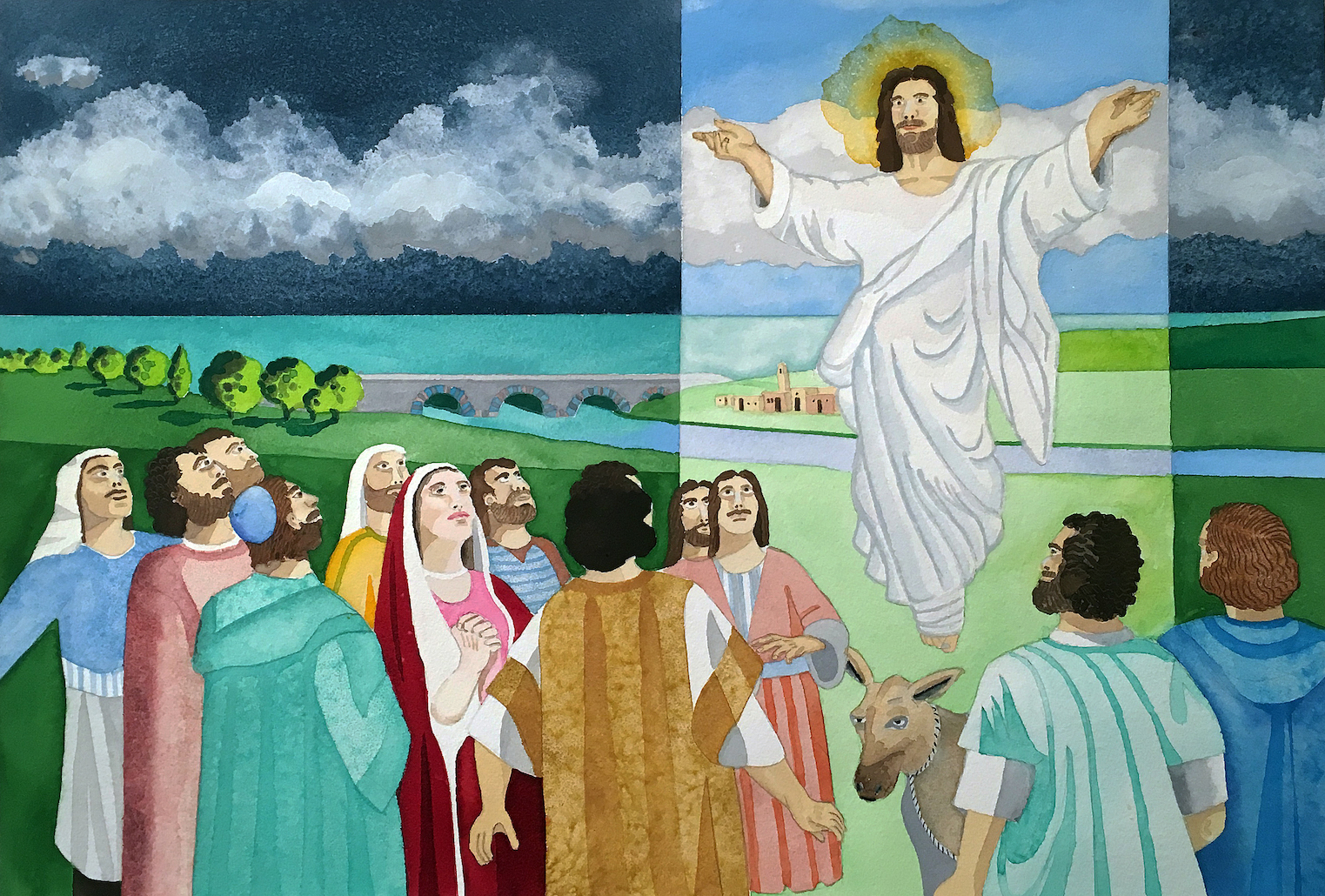

Throughout the exhibition the female body is explored as the medium of exchange for cultural expression and happily this exhibition gives us the opportunity of seeing four of Rivera’s breathtaking Detroit Industry preparatory cartoons, two of which are female figures representing the seed and fruit of the female body. Because of their fragile paper the cartoons are not displayed often.

Much of the “Labor of Love” exhibition becomes a treasure hunt. Spread throughout the museum are nine Isabel Toledo’s playful, sexy, even downright erotic designs for female adornment which are in response to particular themes and moments of the history of art arranged in the chronological galleries. It is intriguing to ferret out the connections to the specific art or gallery theme. A map is provided but, even for a seasoned museum visitor, it’s a joy to walk through the museum, with chance encounters of things that catch your eye, trying to find Isabel’s interventions. It is a clever way to break the museum’s “ideology” and cast a completely different agenda on its organization, and get the public into the galleries.

Isabel Toledo, “Synthetic Cloud,” 2018, Nylon

There are many intriguingly inventive responses and fashion interventions by the Toledos including Isabel Toledo’s design for Michele Obama’s inauguration outfit found in the American Colonial house and interesting twists on the shenanigans of the surrealists, and to Alison Saar’s “Blood/Sweat/Tears” sculpture, but the most engaging is “Synthetic Cloud.” Installed in the “minimalist” gallery and inspired, it appears mostly by Robert Irwin’s diaphanous acrylic disc, “Untitled, “ but as well by the hard-edged paintings and sculpture of Donald Judd, Sol Lewitt, Eva Hesse and Ellsworth Kelly. Above Irwin’s chimerical disc, the most mysterious piece of art in the museum, hang eleven multicolored, nylon, tulle tutus that float like a formation of clouds high above our heads. Layer upon layer of pastel underskirts support the dancing figures that also support the rigid wire bodices of the imaginary ballerinas. Somehow echoing Irwin’s ineffable image of light and shadow, Toledo’s fantastic ballerina clouds are worth the trek.

Panoramic installation view of gallery

Isabel and Ruben Toledo: Labor of Love, Detroit Institute of Arts – Through July 7, 2019