Miami Art week, the mammoth fine art fair comprised of Art Basel Miami Beach plus twenty satellite fairs, events and parties, salted around the city like raisins in a fruitcake, has just ended. It was an all-you-can see buffet of contemporary art, much of it excellent. It’s impossible to see it all without developing a serious case of esthetic indigestion. But my project to see the art coming from the Great Lakes region, and Detroit in particular, made the task more manageable.

A string of fairs located in lavish oversize tents, Scope, Pulse, Untitled, Context and Art Miami, were lined up along the beach and interspersed with large public art works exposed to the sun and air. Art Miami, at 30, which predates Art Basel and is the oldest and one of the most respected fairs, is where I found David Klein Gallery’s booth. This year, the gallery showcased a collection of Detroit artists who will be familiar to anyone who’s been paying attention, as well as a couple of talented newcomers.

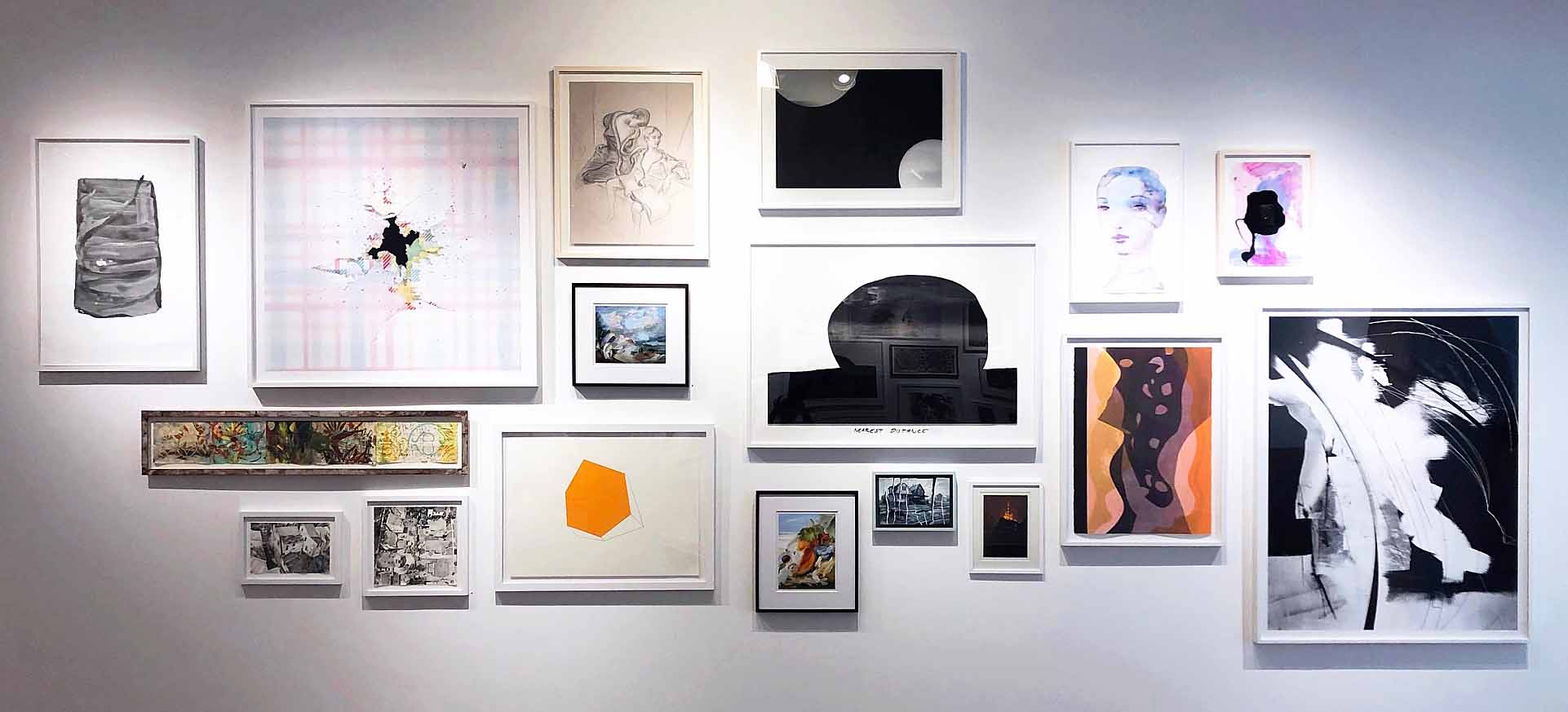

David Klein Booth at Art Miami, Photo by K.A. Letts 2019

Gallerist David Klein told me that the gallery opened its first booth at Art Miami 11 years ago, during the height of the Great Recession, and that they’ve been coming every year since. The booth was anchored by Kelly Reemtsen’s monumental Rise Up.The warm Miami air seemed to billow the voluminous taffeta skirt of her genteel but assertive debutante, and the light in the heavy white impasto surrounding the figure felt a little different on the beach in Miami than it had when I saw the piece in Detroit.

Rosalind Tallmadge and Marianna Olague, two recent graduates of Cranbrook Art Academy, were represented by David Klein in Miami this year. Klein described Cranbrook as “…a great resource for us. Rosalind we met when she was in the painting program [there] and Marianna Olague is also a very recent Cranbrook grad.” Artworks by the two seemed to respond to the ambient Florida sunshine, though in different ways. Tallmadge’s formal mica, glass bead and metal leaf-encrusted artworks, which seem more the product of geology than of art, shimmered, while Marianna Olague’s self-contained and pensive young women occupied a pictorial space suffused with the warm light of her native El Paso.

Marianna Olague, Here Lies Toro, 2019, David Klein Gallery, Art Miami, 2019

Mario Moore, The Visit, 2019, David Klein Gallery, Art Miami, photo courtesy David Klein Gallery

David Klein Gallery has routinely shown the work of African American artists, but suddenly at Art Basel Miami Beach 2019, there was a notable increase in artists of color prominently displayed throughout all the fairs. Mario Moore’s large single-subject portraits were exactly on trend. The self-possessed, casually dressed inhabitants in Moore’s paintings, situated comfortably in their everyday environments, projected confidence and understated dignity.

The highest concentration of Detroit representation was at NADA (New Art Dealers Alliance), which bodes well for the future of the art scene in Detroit. This fair shows work by up-and-coming galleries and artists (and famously provides a hunting ground for more established galleries hoping to poach promising young artists.) Held in the Ice Palace Studios, Nada’s relaxed atmosphere, with some artworks scattered around the grounds and hammocks and picnic blankets provided for physically exhausted and/or visually overstimulated fairgoers, was a welcome change from the more aggressively commercial fairs.

Detroit was represented in the main exhibitors’ section by Simone DeSousa Gallery and Reyes/Finn. And in the NADA Projects section–a sort of junior NADA–I encountered Detroit Presents, a collection of Islamic prayer rug-inspired collages by Anthony Giannini presented by Detroit Art Week.

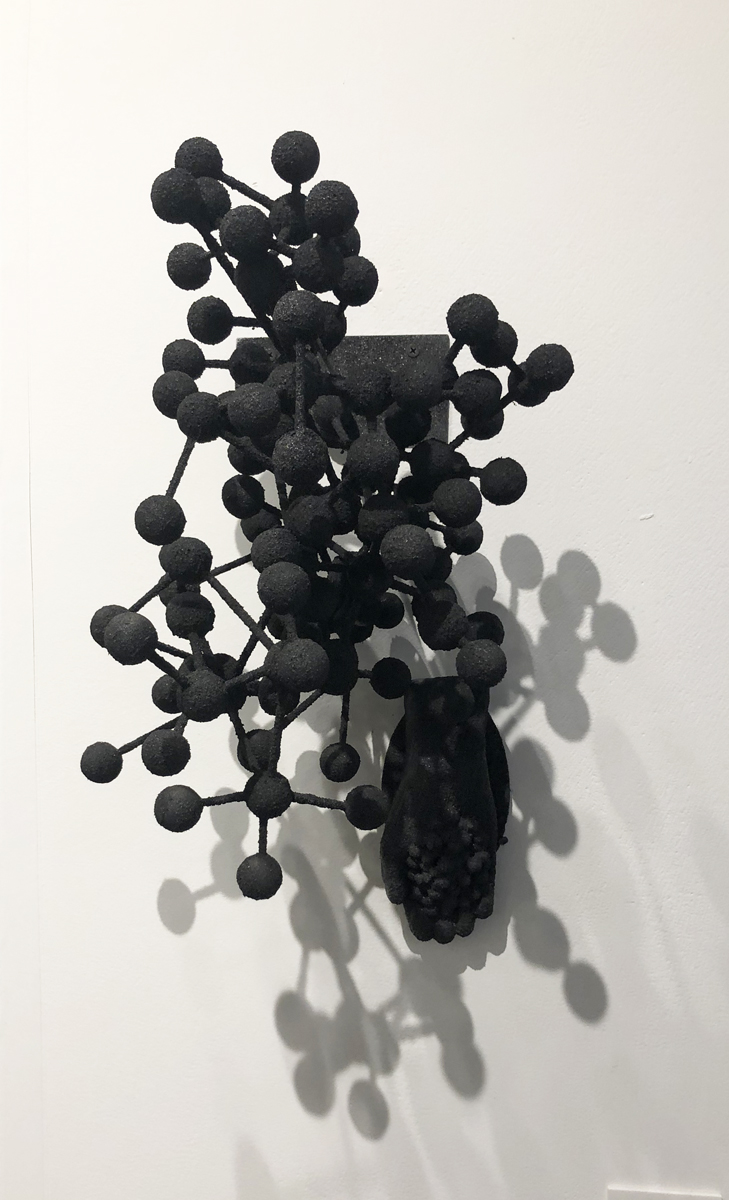

This was the second year that that Simone DeSousa has represented artists at NADA. She chose to exhibit the work of two Detroit-based creatives, Veha Nedpathak and Iris Eichenberg. NedPathak’s richly colored, freeform process-derived paper tapestries, created by her self-invented ritualistic practice, contrasted nicely with Eichenberg’s light absorbing, idiosyncratic black objects.

Neha Vedpathak, So many stars in the sky some for me and some for them, 2018, Simone DeSousa Gallery, NADA (photo courtesy of Simone DeSousa Gallery)

Iris Eichenberg, Untitled, Simone DeSousa Gallery, NADA, photo by K.A. Letts

When I asked DeSousa about her plans for future art fairs, she pointed out that there is considerable expense involved in participating, but the Nada fair makes the most sense for the gallery, and so far it has proved to be a good showcase for the artists and for her. It’s likely that she will to present artists from her gallery there in future.

A more conceptual vibe prevailed at Reyes/Finn, where the frosty glow of Detroit-born Maya Stovall’s hermetic neon signs referred to year dates significant to the artist and referenced coincident meaningful cultural touchstones. These gnomic objects, though compelling in themselves, represent only a small portion of Stovall’s work in performance, installation and video. Co-exhibitor Nick Doyle celebrated common man-made objects raised to monumental scale–a giant wall outlet, a huge, discarded coffee cup–rendered in denim-blue, a color both common and cool.

Maya Stovall, 1959 from 1526 (NASDAQ:FAANG) series, 2019, photo by K.A. Letts

Nick Doyle, Shutter, 2019, Reyes/Finn Gallery, NADA, photo by K.A. Letts

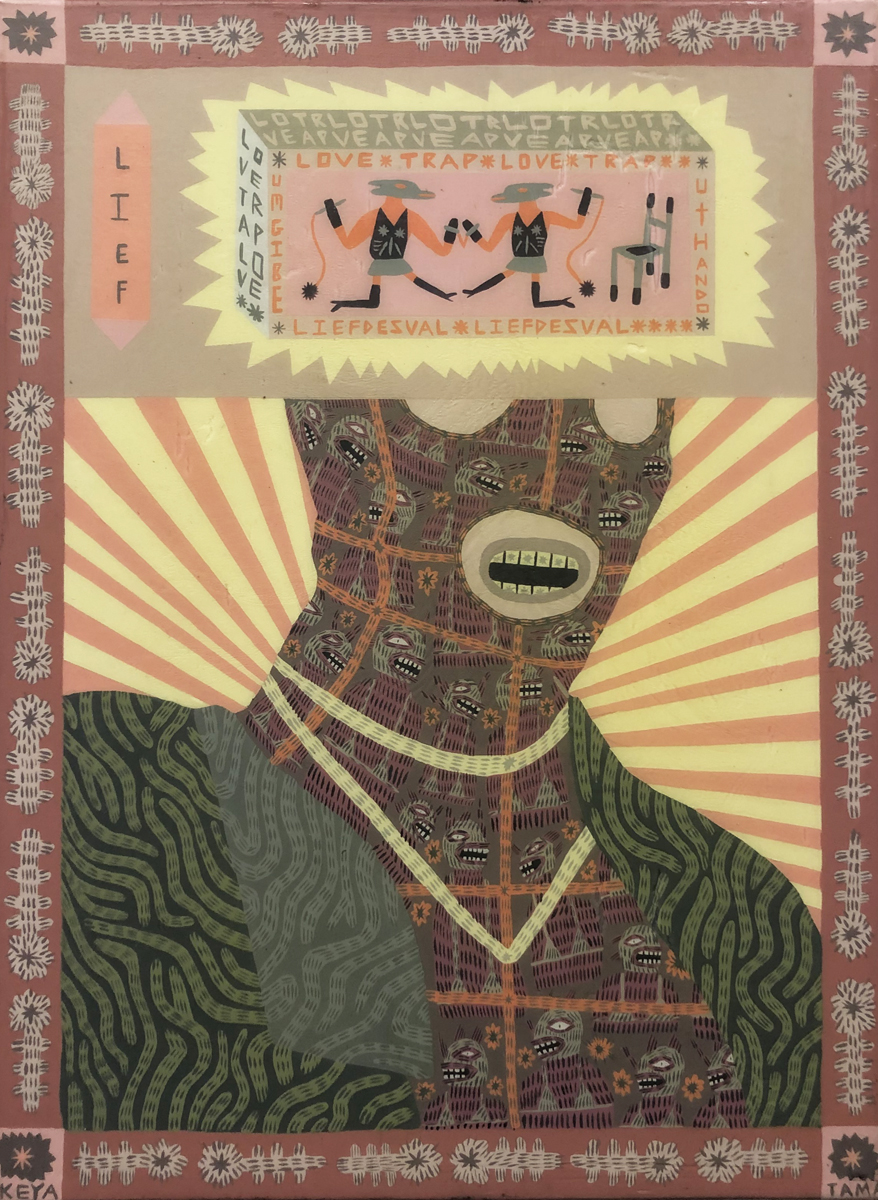

The street art esthetic that is so prevalent in Detroit was noticeably absent from the established fairs, with the exception of Scope, where I saw a pair of Chicago galleries, Vertical and Line Dot Editions, that carried the flag for that way of thinking and making. The Mana Wynwood neighborhood is the place to see that esthetic expressed. A lot of the art is on the street, and it’s rude and risky. Some of the most impressive work that I saw in this vein wasn’t in a fair at all, but at Mana Contemporary, where Miami’s indigenous art community has a home. There, I saw work that hasn’t (yet) made it into the mainstream unless you count a small piece by Karl Wirsum that I glimpsed in the back room at Corbett vs. Dempsey in their Art Basel Miami Beach exhibit. And Detroit/Brooklyn-based SaveArtSpace.org engaged in its usual end run around the establishment, with three street-side bus stop ads featuring the work of Chris Pyrate, Brian Cattelle and Peat “EYEZ” Wolleager.

Keya Tama, Love Trap, Mana Contemporary, Wynwood neighborhood, photo by K.A. Letts

Peat “EYEZ” Walleager, EYE Want You by, SaveArtSpace.org, (photo courtesy of SaveArtSpace.org)

A visit to Miami Art Week is probably the most efficient way to take the pulse of the art scene now, in all its diversity and variety, even though you may come away troubled, as I did. I found that the art world is just another part of the real world, where the .1 percent, by virtue of its vast resources, decides how art is defined and commodified. And lingering in the distance like a thundercloud is climate change, a looming presence that’s hard to ignore while looking at art on a vulnerable beach.

Miami Art Basel, December 2019