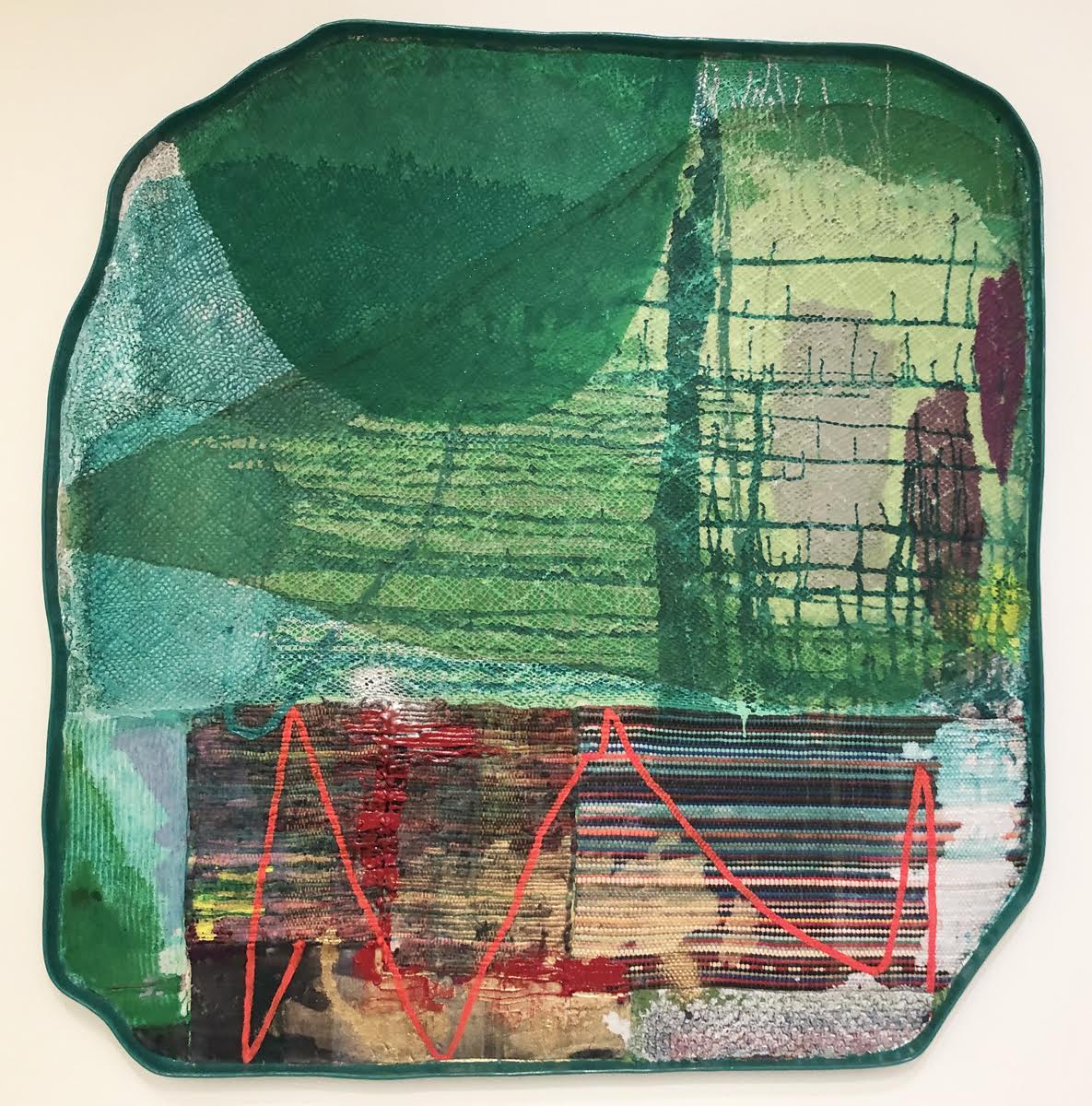

Owlkyd (AKA Darius Littlejohn) has a solo exhibition at Images Works in Dearborn, MI

Installation image courtesy of the gallery

Image Works opened the Detroit-based artist Darius Littlejohn’s artwork on December 2nd with Expressionistic figures produced in a lushness of high contrast color using computer-based software and printed on paper using a large inkjet printer. Chris Bennett, owner and curator of Image Works says, “Deeply impacted by the Neo-Expressionist works of Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Surrealism of Pablo Picasso, Owlkyd melds his love of Realism with the abstract ideals pioneered by the two to find beauty in the clash of these disciplines.”

Owlkyd, What’s It To Me, 40 x 50”, Digital artwork on paper. 2022

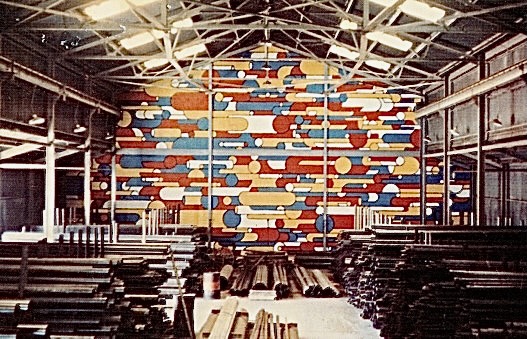

To place the artist Owlkyd in context, I recall following a similar artist in the mid-1970, Richard Lindner, the American/German artist born in Hamburg who moved to the United States in 1941 and taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. Lindner’s works from this period are often characterized by a vague sense of nostalgia and sexual undertones. In Linder’s figurative work, he created powerful images that were both exotic and surreal in concept and bold in their use of high-contrast color. Lindner’s figures are reminiscent of those by Fernand Léger

Richard Lindner, The Grand Couple, oil on canvas, 60 x 72”, 1971

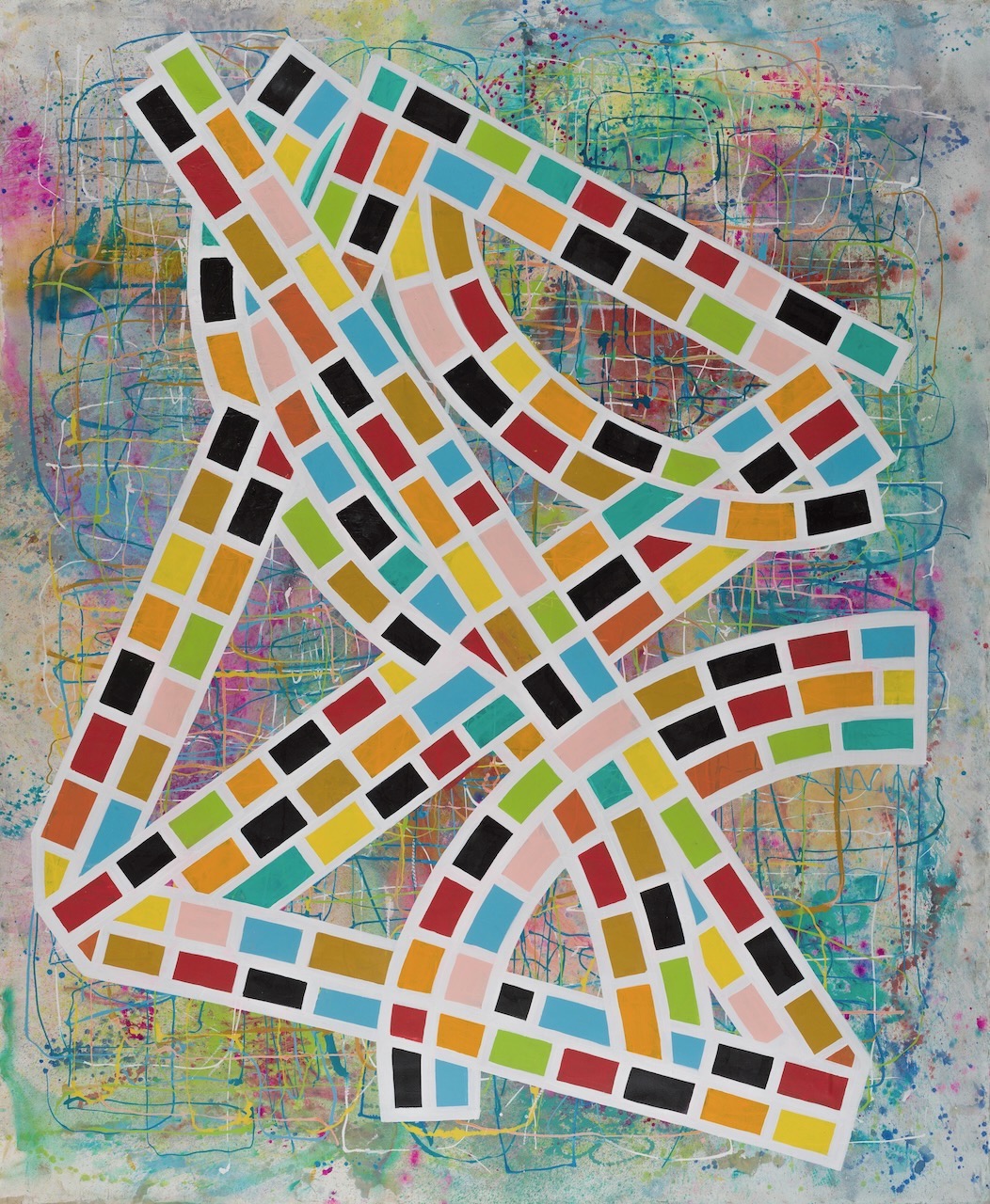

The works by Owlkyd are created in a digital environment using XP-Pen 15” drawing tablet, connected to his workstation using PaintTool Sai software, and printed out 40 x 50” using a large inkjet printer. These images are fluid Neo-Expressionistic portraits that use profiles of people with small design images spread out over the compositional spaces and set against various backgrounds.

Owlkyd, Regal, 40 x 50”, Digital artwork on paper. 2022

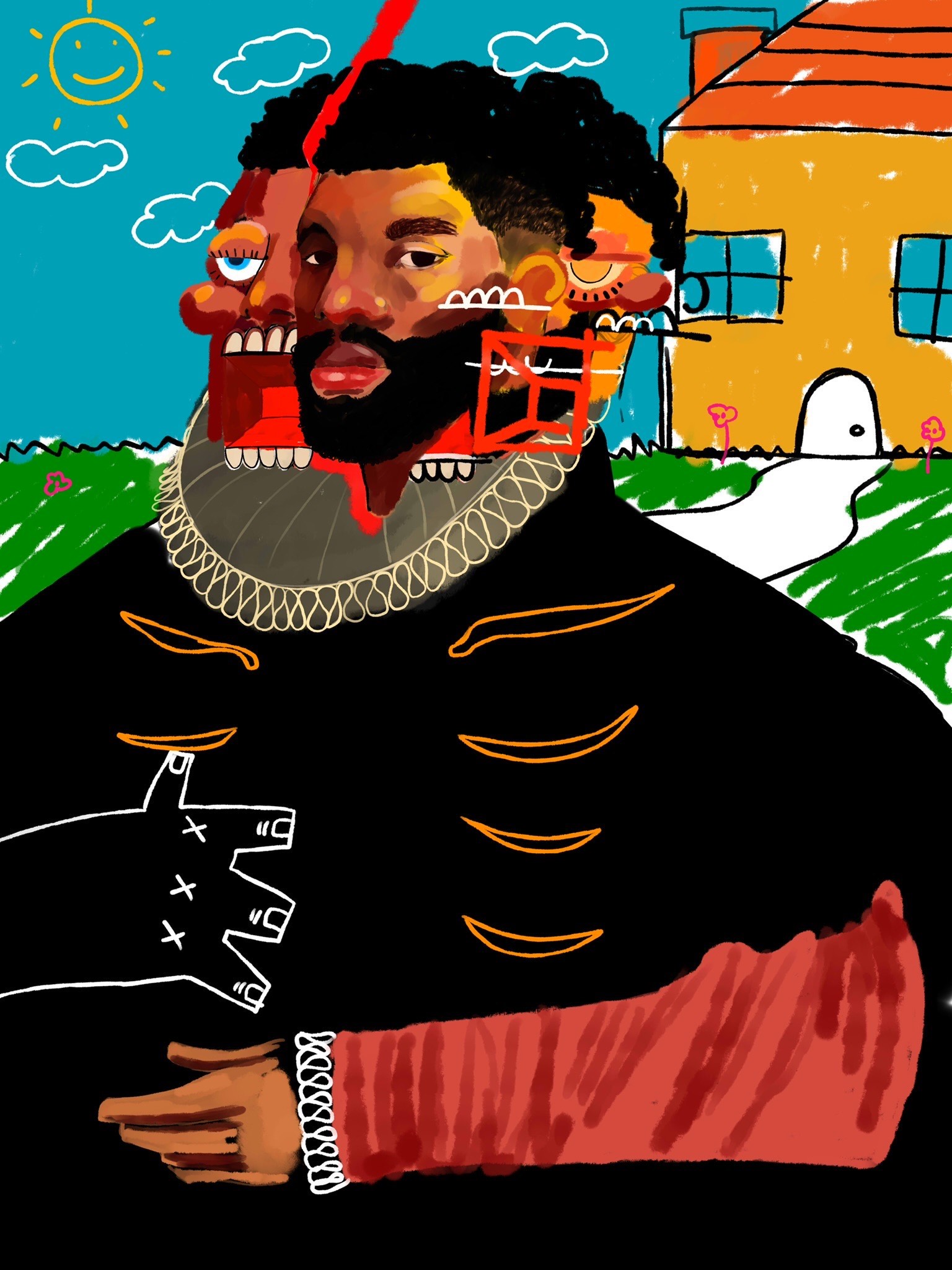

The work Regal has the figure set against a simplistic landscape with a figure that could be considered a self-portrait; again, dispersed throughout the composition are small design elements. At the same time, one arm is rendered in a realistic, painterly fashion, while the other has a flat white outline with three fingers. The childlike background contrasts with the uniformed figure, part realistic, part cartoonish. The expression of that contrast reaches out and grabs the viewer.

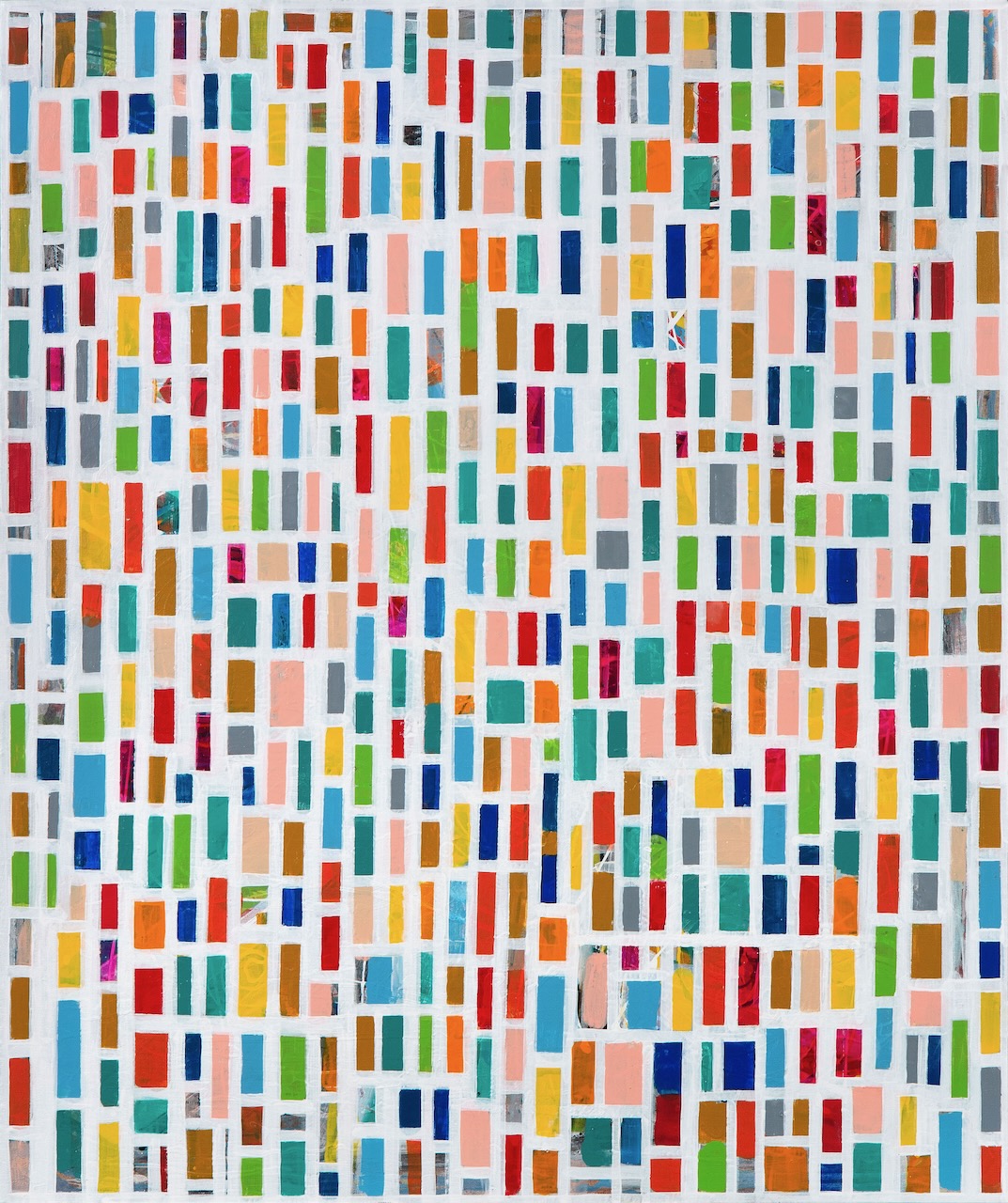

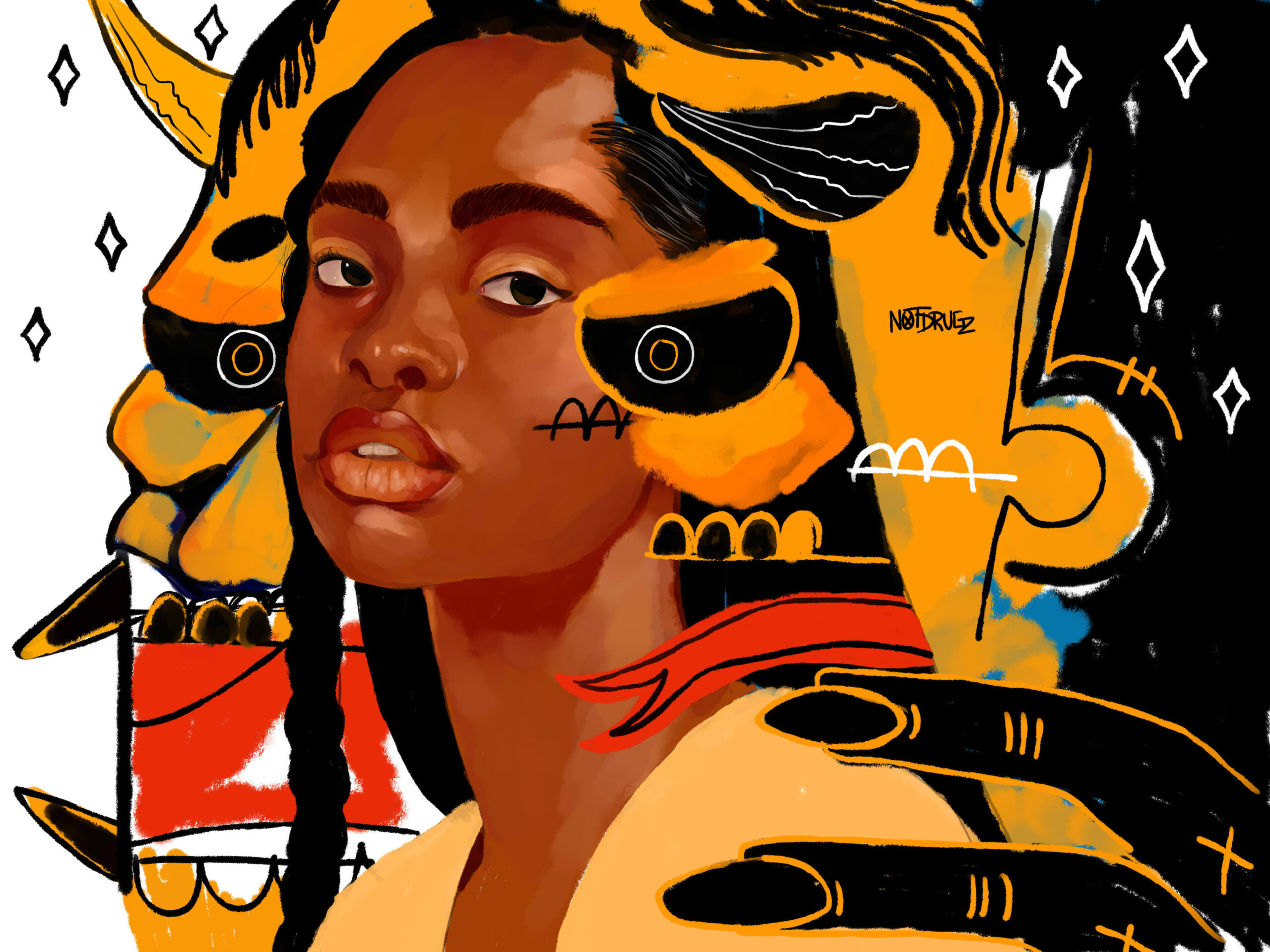

Owlkyd, Is My secret safe, 40 x 50”, Digital artwork on paper. 2022

This three-quarter realistic female portrait, Is My Secret Safe, is heavily expressionistic in its surroundings, with small symbols contrasting against an abstract background. Separate from the first two portraits, the figure looks directly at the viewer with a listless expression that draws the viewer in. Owlkyd, in our conversations, mentions the artists who have been influenced well known most, like Picasso, Basquiat, and then Ten Hundred (Peter Robinson), a Michigan artist who specializes in bright, colorful, imaginative character work inspired by cartoons and anime, and graffiti, childlike imagination, comics, and world cultures.

Ten Hundred, (Ted Robinson), Bass Player, Digital Artwork example.

More evident in this figure, No More Opps, with cartoon images on and around the face, is again a self-portrait dressed in regal apparel.

Owlkyd, No More Opps, 40 x 50”, Digital artwork on paper. 2022

Owlkyd, (AKA Darius Littlejohn) supports his livelihood by working in the auto industry managing auto inventory systems for Chrysler. When asked about art school, he says, “Like many, I didn’t really have the means to pursue any formal training so I am wholly self-taught standing on my various influences.”

Owlkyd, Galactus, 40 x 50”, Digital artwork on paper. 2022

Throughout these portraits are words that express the message, “Not Drugs” and in this work Galactus, it is prominent. The message appears in the female portraits only and not in male portraits. It leads this writer to believe it is a statement that has particular meaning for females and reflects the artist’s need to send them a message.

Image Works, located on the far east side of Dearborn, specializes in archival pigment printing, also known as giclée or inkjet printing, for reproducing photographic and fine art imagery. Housed in a storefront on Michigan Ave, it uses the all-glass entrance as its gallery.

The Window Project at Image Works is on display through January 28th, 2023 – Closing Reception: Saturday, January 28th, 1-4 pm