Heloisa Promfret & Neha Vedpathak Exhibition Installation image, 2018

There is definitely a synergy in the new exhibition at the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary art. These non-objective abstract works go beyond being executed by two female artists, working with unconventional material, approximately the same scale. The director of the Center fo Contemporary Art, George N’Namdi, is bringing together two artists that share a sensibility that involves an unexpected process. The exhibition opened April 13, 2018 with the work of Neha Vedpathak who works picking at Japanese paper and Heloisa Promfret who involves the palimpsest process where layers of paint are scratched to reveal paint beneath. The synergy that I speak of here is the juxtaposition of energy, both physical and psychological, creating work you cannot ignore.

Neha Vedpathak, Detroit, Plucked Japanese handmade paper, acrylic paint, thread, 70 x 68″ 2017

The large, 70 x 68” paper construction, titled Detroit, is layered in a way that allows for transparency to play a part in the composition. Neha Vedpathak uses shades of yellow that surround this broken cross and dominates the interior. She uses the term “plucking” when she picks the surface of the paper, appearing both solid and transparent, while occasionally using acrylic polymer for strength.

She says “I am drawn to paper, it is familiar, flexible and a giving natural material. I have been using Japanese hand-made paper in small parts in my paintings over the years. But since 2009 ”paper” has become the main focus of my investigation. After playing with this paper for a while, I developed a technique I call ‘plucking”. ”Plucking” is the main technique used in all my paper sculptures and installations. Here, I separate the fibers of the Japanese hand-made paper using a tiny pushpin. The resultant paper resembles a lace fabric, which I then use to make individual works.”

Neha Vedpathak, Hold Tight, Plucked Japanese handmade paper, acrylic paint, thread, 34 x 34″ 2018

The piece Hold Tight resembles a terrain map with colors differentiating borders of countries around a body of water. Here the contrasts between solid and textured surfaces are more evident. The efflorescent paper delicately creates a latticework that draws the viewer close.

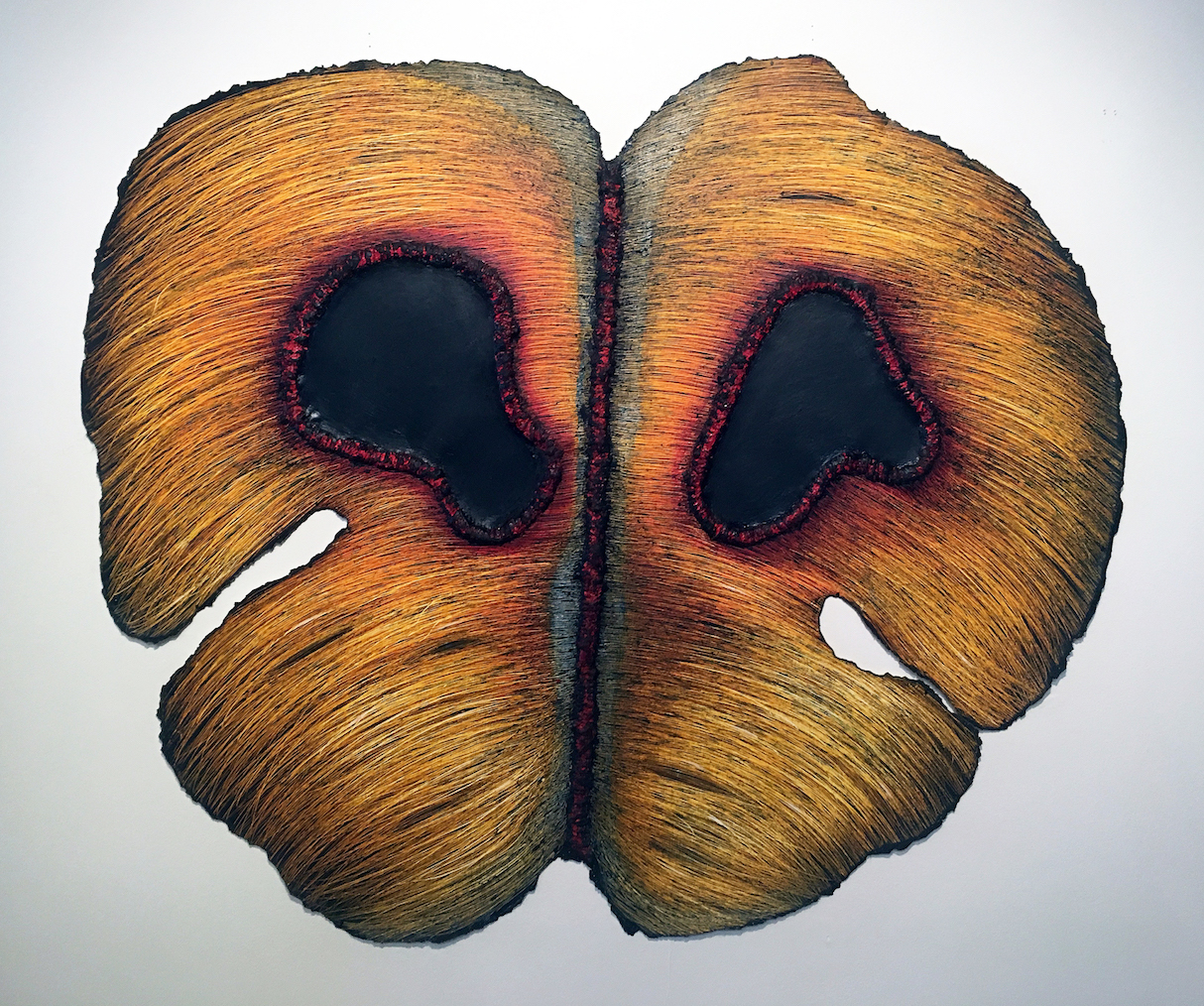

Heloisa Pomfret, Untitled (Threshold Series), Oil on Canvas, 34 x 39″ 2018

When first confronted with the work of Heloisa Promfret, as in Untitled, 34 x 39” this viewer gets a feeling of seeing the cross section of a walnut when cut in half using a band saw to reveal the interior design. But on closer observation there is a transformation from this first impulse to acknowledging a more mark-making technique that involves color and texture. In what she describes as her Threshold Series we see canvasses that are cut, re-stitched, and the paint is scratched with metal blades revealing the colors below.

She says “My work is about the energy, order and chaos that occurs during

psychological or physical stress, which serve as theoretical support to the mark-making and constructs of my work. The surface is often an analogy to the body and memory, in which experience occurs and is transformed. The visual elements of the brain, along with its scientific charting and diagrams, serve as inspiration and a starting point of abstraction for paintings/drawings and installations, in both traditional and non-traditional materials.”

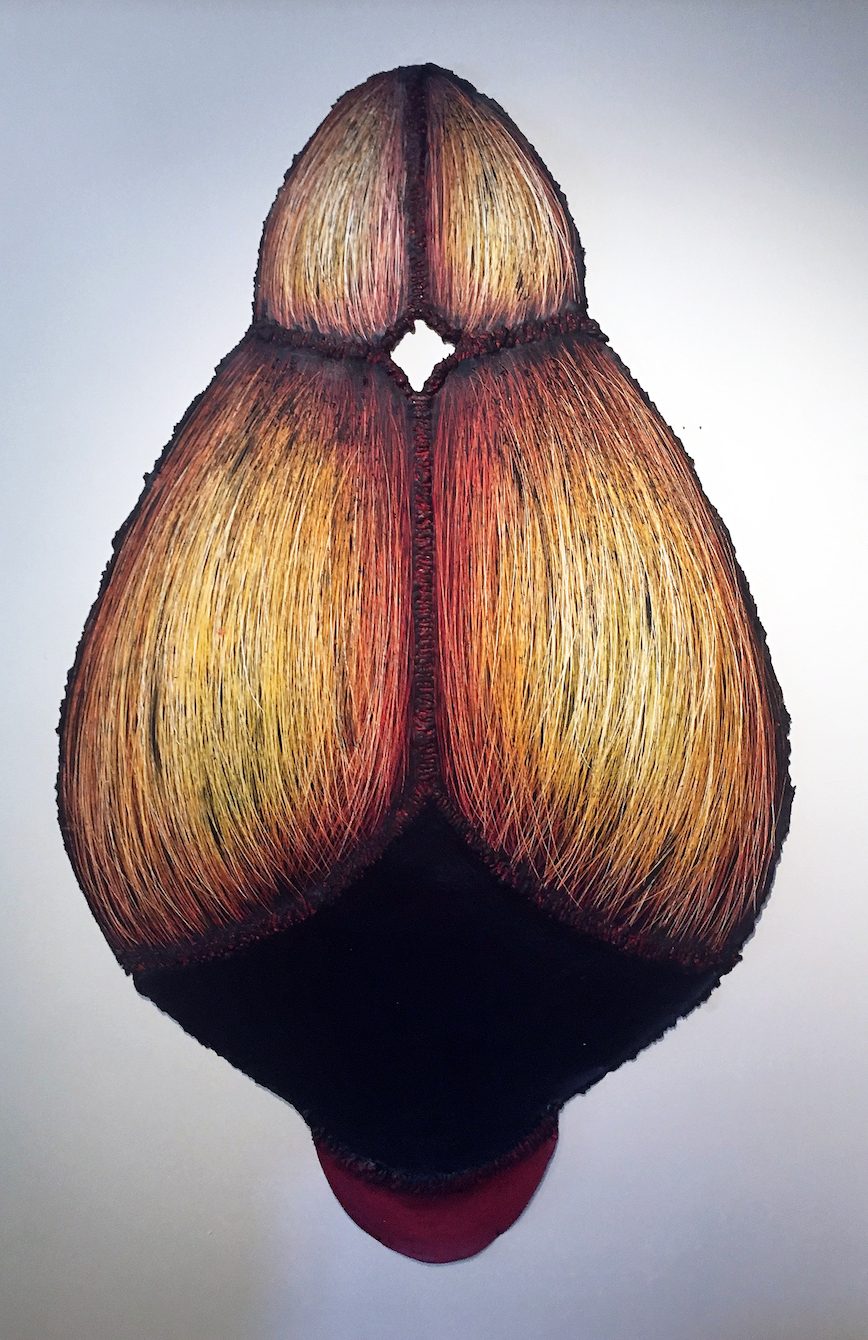

Heloisa Pomfret, Clarity II (Threshold Series) Oil on canvas, 33 x 53″, 2018

In Clarity II there is a strong feeling of the feminine for this viewer, almost like an embryo in its early stage of development. The dominating symmetry is something we would find in nature, like a seed, plant or early development in an insect. This flat high contrast image takes on a sense of three dimension using light and color to create a sculpted form. In addition, her work includes “Maps”, an installation of over 250 images cut from truck tire inner tubes.

Helosia Promfret’s work here, is called “Threshold”. She earned her MFA from Wayne State University in 2002. Helosia Promfret was born in Soa Paulo, Brazil, lives and works in Detroit, Michgan.

Neha Vedpathak in her work called “Of The Land”. She earned a five- year diploma in Fine Arts from Abhinav Kala Maha Vidhyala, Pune, India. She currently lives and maintains a studio in Detroit, Michigan.

These two solo shows will be on display at the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art through May 5, 2018.