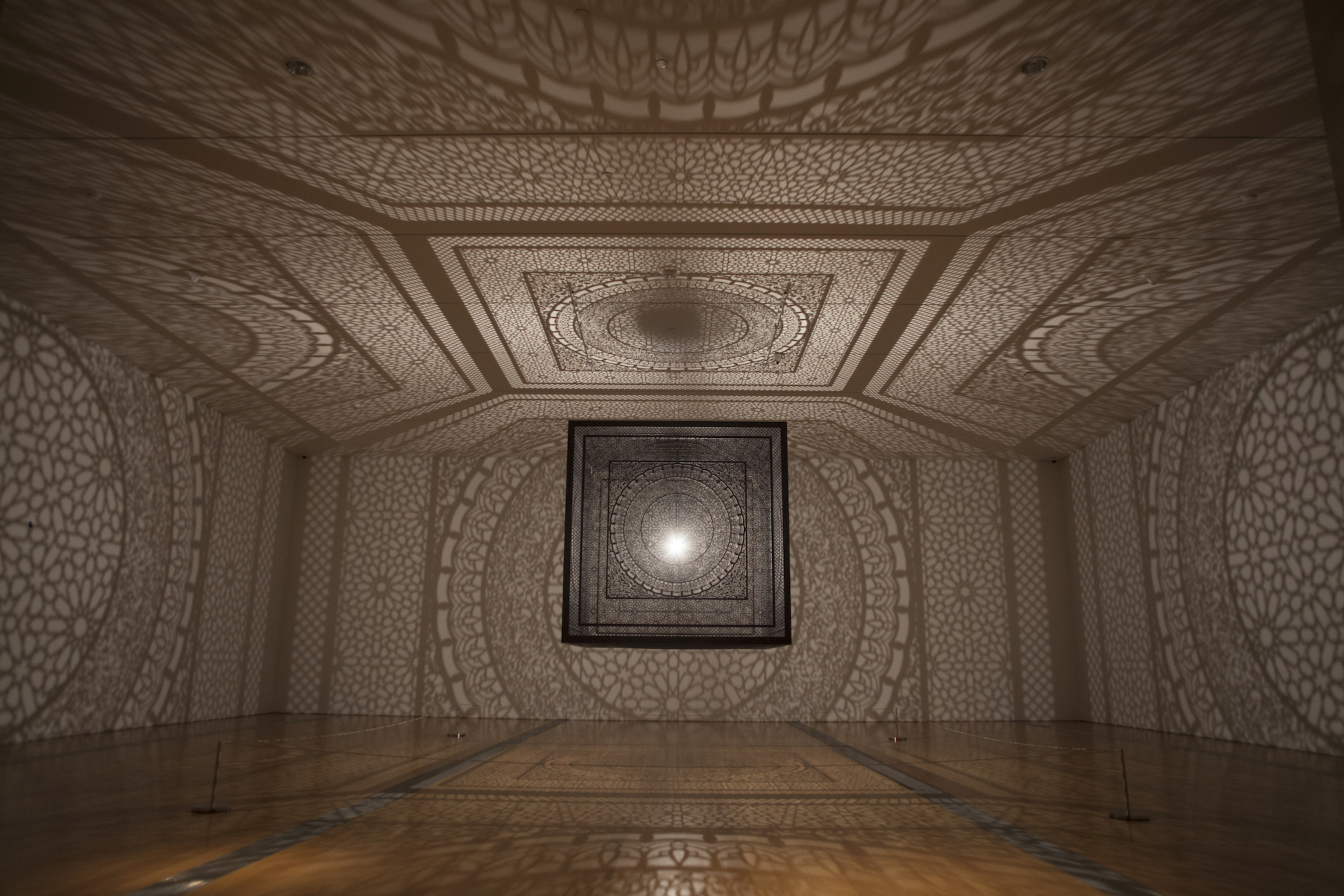

Anila Quayyum Agha (American, b. Pakistan 1965). Intersections, 2013. Laser-cut wood, 6.5 x 6.5 x 6.5 feet. Courtesy of the Artist.

Anila Quayyum Agha’s ethereal sculptural installation Intersections is likely the most photographed work of art in Grand Rapids at the moment, surpassing even the city’s iconic, blazing-red Calder. At Artprize 2014 (the city’s annual public-art festival), Intersections won both the People’s Choice and Judges’ Choice awards, and now, through the end of Summer, it returns to the Grand Rapids Art Museum where it made its auspicious debut. It was a work calculatedly fashioned to appeal across social and cultural demographics, and if Instagramability is a worthy criterion of a work’s public appeal, then the artist certainly succeeded.

The work is the star of a pair of closely related solo exhibitions on view in adjacent gallery spaces, one showcasing Agha, and the other featuring Iranian artist Monir Shaharoudy Farmanfarmaian. There’s a thematic continuity between their distinctive styles that make the pairing work almost as a single show. Both artists apply sophisticated tessellations and kaleidoscopic patters so characteristic of visual culture in the pan-Arab world, and both artists explore the visual possibilities of reflected light and cast shadow. Their works are also both—to some degree– participatory and interactive.

Monir Shaharoudy Farmanfarmaian, Installation image, Courtesy of the Grand Rapids Art Museum

The first exhibition space contains Mirror Variations, Farmanfarmaian’s luminous glass sculptures which represent an inventive fusion of traditional Persian art mixed with the American abstraction the artist encountered during her formative years in New York between 1945 and 1957, where she met art-world luminaries like Willem de Kooning and Louise Nevelson. (In 2015 her work came full circle; New York’s Guggenheim awarded the artist her first solo American show—perhaps a curiously late honor for an artist and socialite of such import that she and her husband once played host to President John and Jackie Kennedy in Tehran.)

Inspired both by Arabic architecture and by principles of Sufi geometry, Farmanfarmaian’s work applies repetition and progression of simple shapes. Like mosaics in 3D, her sculptures comprise tens of thousands of individual glass components which reflect light, diffusing fragmented geometric shapes across the gallery walls, ceiling, and floor. One pentagonal sculpture—though prohibitively stowed behind glass on a pedestal—reflects light onto the ceiling and into the viewer’s space, directly involving the GRAM’s architecture into her work. The lack of artisans in the United States able to help execute such detailed cut-glass work as this is partly why the artist eventually returned to her home country in 2004 after over 20 years of exile initiated by the Iranian Revolution.

Monir Farmanfarmaian (Iranian, b. 1924). Tir (Convertible Series), 2015. Mirror, reverse-glass painting, plaster on wood, 63 x 63 x 6 inches

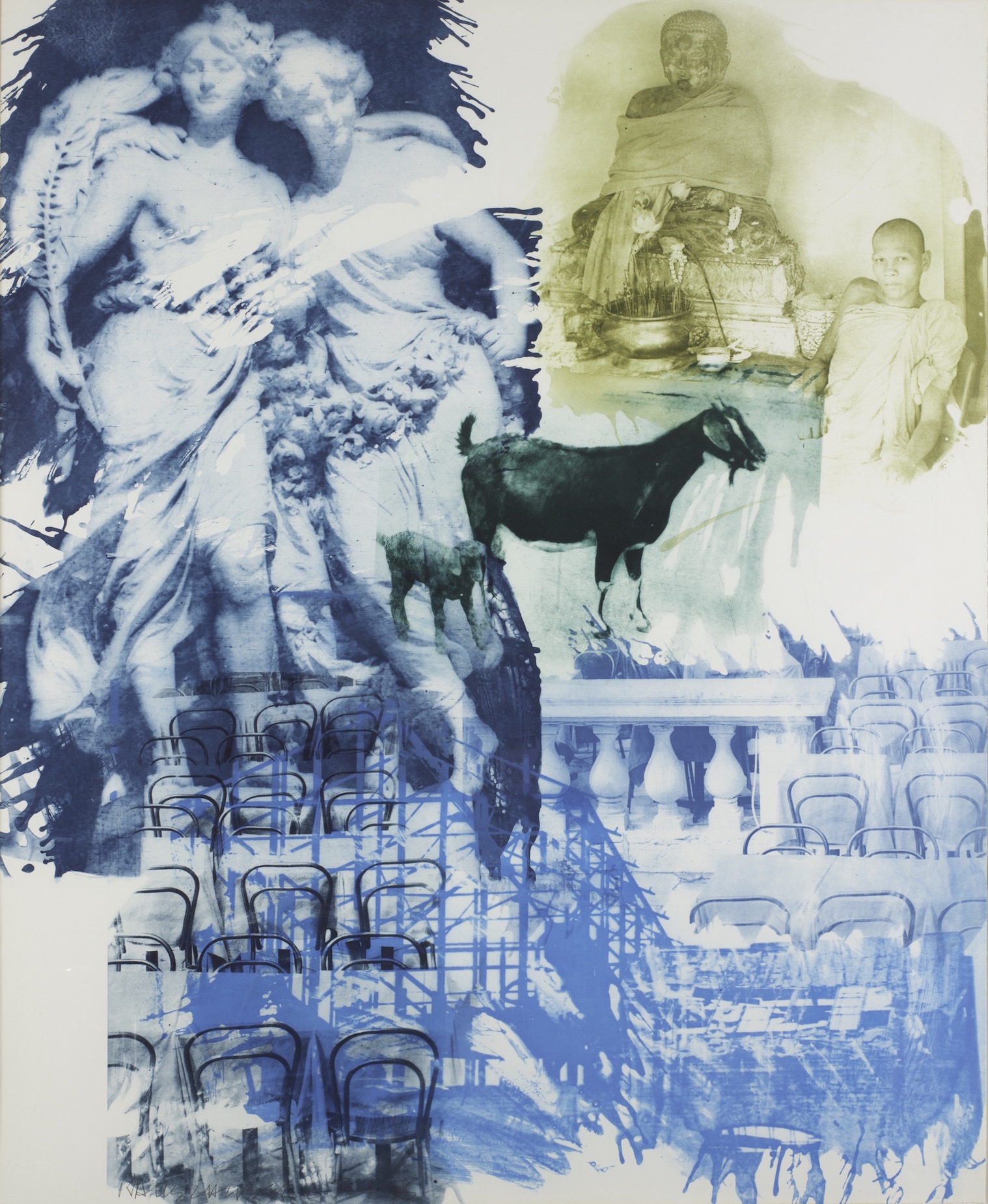

These stately, ordered sculptures might seem the polar opposite of the often noisy, raucous world of the Postwar New York School, but some of her hanging sculptures invite a certain relinquishment of control that seems to parallel the likes of Robert Rauschenberg—particularly his playfully interactive Synapsis Shuffle (incidentally, a series of paintings which the GRAM exhibited in this very room back in 2012). Her Convertible series explores the myriad of varying geometric possibilities that can be created with a set of identical, interlocking shapes. Each polygonic component is a fairly complex work in its own right, but the specific way they are arranged on the wall remains entirely fluid, ever-changing wherever they happen to be installed.

The second major gallery space is entirely devoted to Agha’s Intersections. The work is a suspended black cube (about 7 feet square) crafted out of laser-cut wood, and inside a high-power bulb blasts the form’s intricate geometric shadows onto the gallery’s walls, ceiling, and floor, transforming every cubic millimeter of the space. Its patterns derive from architectural elements of Spain’s Alhambra,the famed 14thcentury Nasarid dynasty palace and fortress. It’s visually striking, but the work is conceptual as well. Agha states that growing up in Pakistan as a female, she was not allowed to enter mosques, and with Intersections, wished to create a work which was open and accessible across all demographics. Indeed, there’s something democratic and participatory about seeing yourself silhouetted on the gallery wall alongside the shadows of other visitors, all invariably with phones drawn, ready to share the moment on social media.

Video interview with Agha

In an auxiliary exhibition space, viewers confront a final bit of shadowplay. A circular sculpture comprising hundreds of identical triangular shapes is affixed from a wall and tactfully illuminated from three different angles. The shadows it casts resemble a mash-up of a Venn-diagram and a series of tessellations by M.C. Escher.

Together, Mirror Variations and Intersections both manage to tactfully translate centuries-old Arabic visual culture into the language of 21stCentury abstraction. And both artists manipulate light to transform a gallery space, creating works that transcend the beautiful and perhaps approach the sublime. Their works slow us down—even in an art museum, after all, one is tempted to rush through to take everything in, spending, according to one study, less than 30 seconds in front of each painting. But here the artists invite us to linger, and these exhibitions suppress our impulse to hurriedly move on the next thing.

Grand Rapids Museum – through August 26, 2018