Installation image, N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art, All images courtesy of the Detroit Art Review

Black History Month during February is an annual celebration of achievements by African Americans and a time for recognizing the central role of blacks in U.S. history, a story that begins in 1915, half a century after the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States. It was in September, the Harvard-trained historian Carter G. Woodson and the prominent minister Jesse E. Moorland founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH), an organization dedicated to researching and promoting achievements by black Americans and other peoples of African descent.

George N’Namdi’s Center for Contemporary Art opens this new exhibition in celebration of the work of Romare Bearden, an African-American artist renowned for his collages and photomontages, a technique he began to experiment with in the 1950s, establishing his reputation as a leading contemporary artist.

Romare Bearden, Cora’s Morning, Collage and Watercolor, 11 x 14, 1986

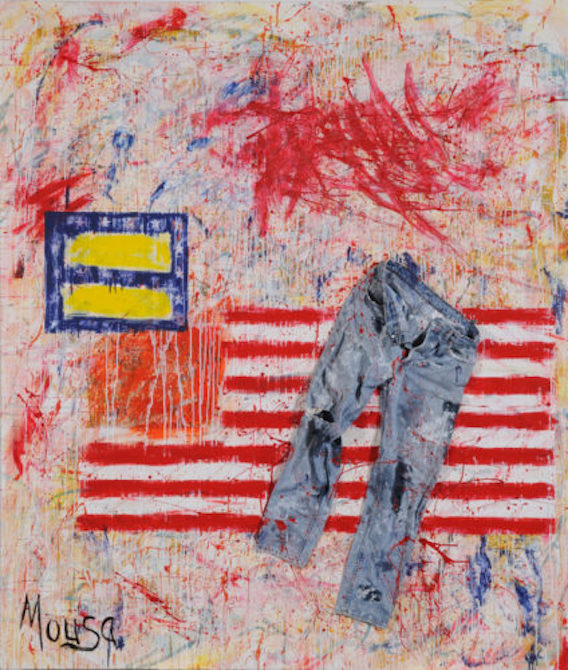

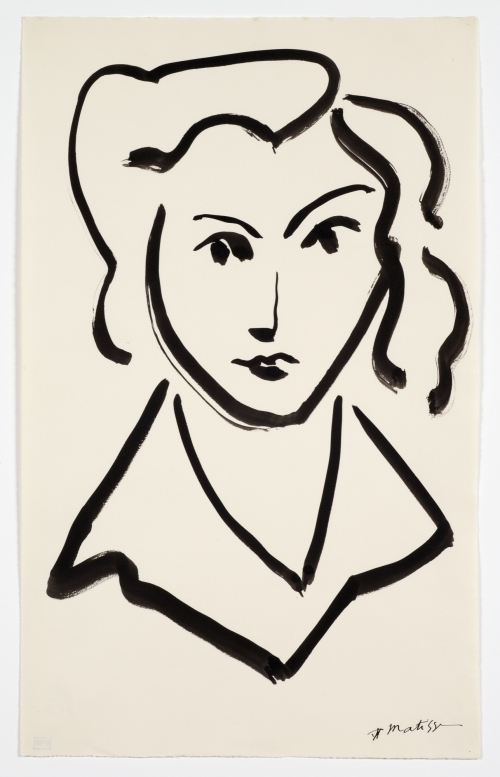

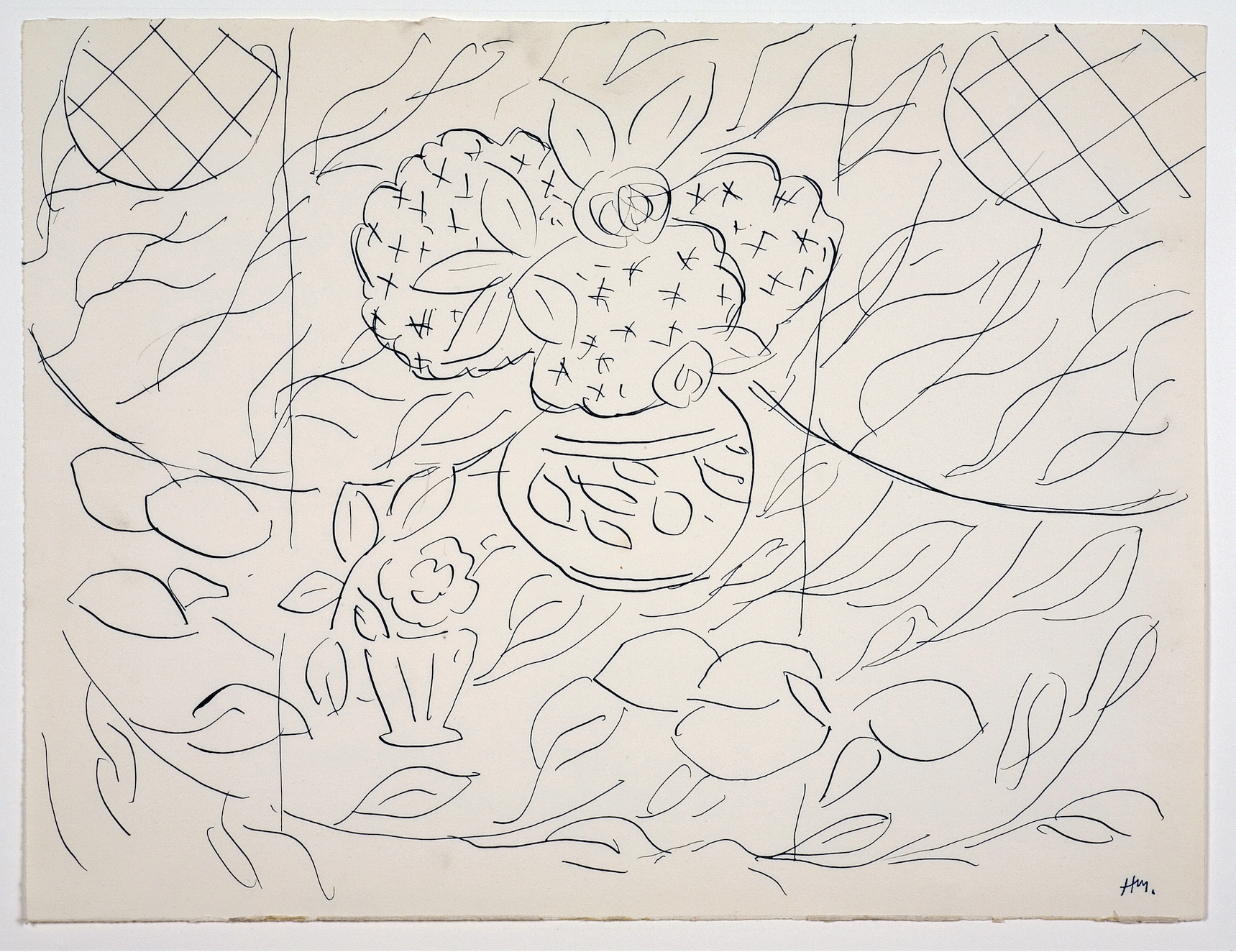

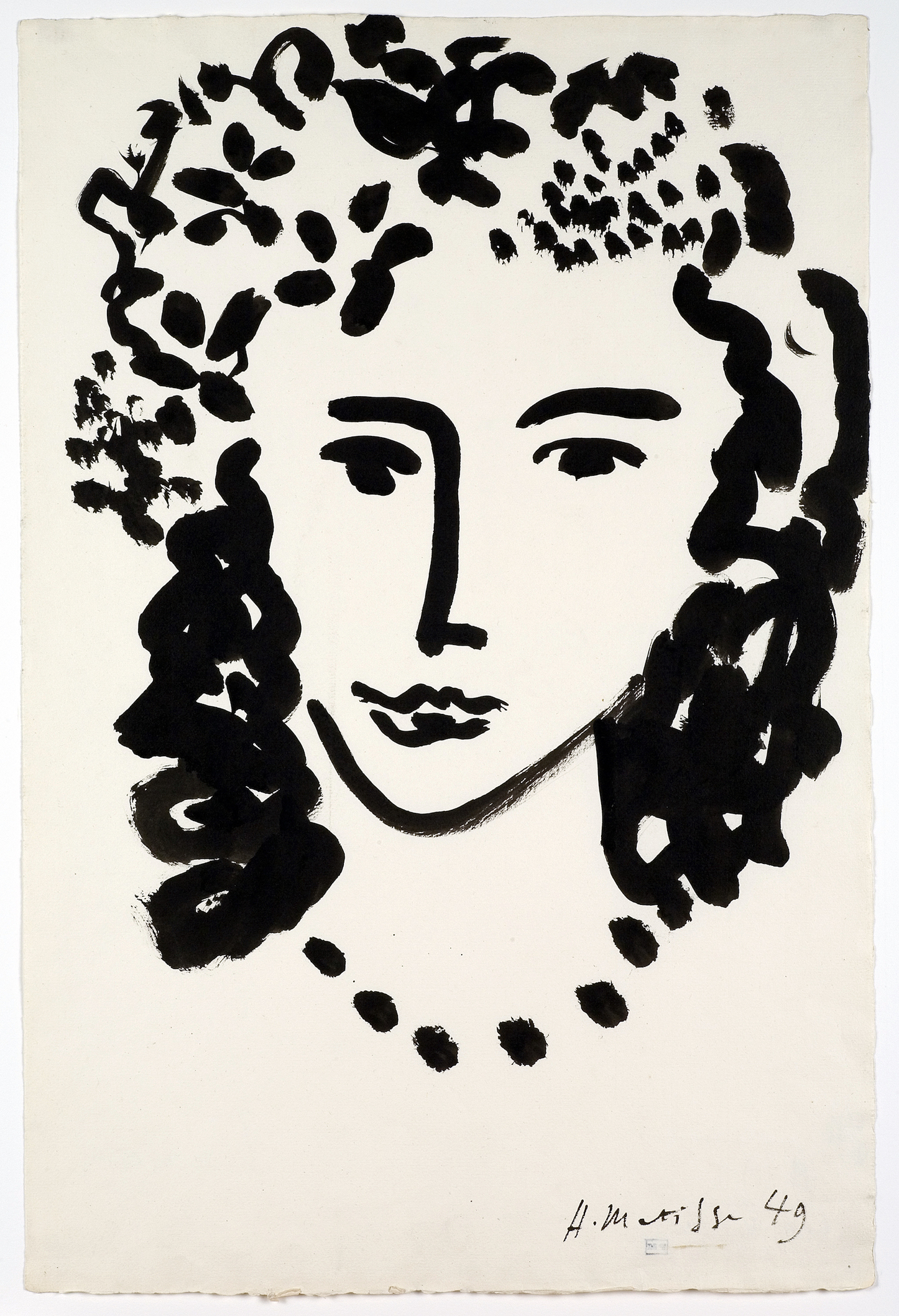

Although influenced by modernists such as Henri Matisse, Bearden’s collages also derived from African-American slave crafts such as patchwork quilts and the necessity of making artwork from whatever materials were available. In this exhibition, he uses images from mainstream pictorial magazines such as Look and Life, and black magazines such as Ebony and Jet. Bearden inserted the African-American experience, its rich visual and musical production, and its contemporary racial strife and triumphs, into his painted collages, thus expressing his belief in the connections between art and social reality. Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso introduced collage into the modernist vocabulary. As a result, Bearden located a methodology that allowed him to incorporate much of his life experience as an African American, from the rural South to the urban North and on to Paris, France.

Romare Bearden, Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, 35 x 29″, 1974

From a series of prints called the Prevalence of Ritual, Bearden reconfigured age-old stories as allegories of modern life. In John the Baptist he drew on the biblical story of Salome, who had performed a dance for King Herod that so pleased him he offered to grant anything she might ask. At her mother’s urging the young girl requested the head of John the Baptist, who had spoken out against her mother’s marriage to the king. The masklike heads of the figures in John the Baptist blend West African and Egyptian visual traditions with a narrative about vengeance and naïveté.

Romare Beraten, Mecklenburg Memories, Collage and Watercolor, 14 x 17″

Drawing upon the recollections of his Southern roots for inspiration, Bearden conjured up both his childhood memories and the shared memories of his ancestors. Bearden absorbed the traditional rituals of the church, the hymns and gospels, sermons and testimonies; as well as the traditional rituals of the family, the music of the kitchen, the outdoor wash place and fire circle, which permeated his upbringing. The work in many of these watercolor/collage pieces is the flatness of the composition combined with the strength of strong primary colors.

Bearden’s career as a painter was launched in 1940 with his first solo exhibition in Harlem and then another, four years later, at the G Place Gallery in Washington, DC, while he was serving in the Army. In 1945, shortly after his discharge, he joined the Kootz Gallery on 57th Street and exhibited there for the next three years. He then traveled to Paris on the G.I. Bill in 1950 where he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1964, he was appointed the first art director of the Harlem Cultural Council, a prominent African-American advocacy group. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1972. He died in New York City in 1988.

Romare Beraten, Autumn of the Rooster, Lithograph, 18 x 24″, 1983

Romare Bearden’s museum retrospectives include those organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, NY (1971); Mint Museum of Art in Charlotte, NC (1980); Detroit Institute of the Arts in Detroit, Michigan (1986); Studio Museum in Harlem in New York, NY (1991); and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (2003). His work is represented in public collections across the country including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Studio Museum in Harlem, NY.

Romare Bearden – through March 31, 2018